Features

They provide the food we eat, the medicines we take, the fuel we use – and, of course, the oxygen we breathe. Plants have been indispensable to human beings for millennia, having a profound and often unexpected impact on our everyday lives.

In his new book, Dr Stephen Harris from the Department of Plant Sciences takes us on a journey through western civilisation, presenting the stories of 50 key plants – from cannabis, carrot and cotton to rice, rubber and rose.

Dr Harris, University Research Lecturer and Druce Curator of the Oxford University Herbaria, picked out three important species for Science Blog. His book, What Have Plants Ever Done for Us? Western Civilization in Fifty Plants, is out now.

Barley: A cereal first domesticated from a common grass in the Fertile Crescent. Barley was the staff of life, whether as bread or beer, for western civilisations for thousands of years. During this period, barley helped people understand chemistry and domesticate yeasts, enabling the transformation of low-value raw materials into high-value products. Furthermore, barley grains became important in the development of currency systems and the standardisation of units of measurement. Today, barley is important in quenching our thirst for alcohol (beer and spirits) and as an international commodity and animal feed.

Coffee: Originally from the mountains of southwest Ethiopia, coffee has become a global source of caffeine, the world's most widely used legal stimulant. Annually, we consume the equivalent of 100,000 tonnes of pure caffeine from botanical sources such as coffee, tea and chocolate. The first English coffee houses were established in the mid-1600s and became associated with the socio-political and intellectual revolutions of the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, most of the world's coffee beans are produced in the South America. One of the periods of Brazilian economic expansion in the 19th century became known as the coffee cycle, which generated vast economic wealth but contributed to the destruction of one of the world's biodiversity hotspots, the Atlantic forest.

Thale cress: A weed of disturbed habitats which is useless as food or medicine but has become a model for all aspects of experimental plant sciences research, ranging from population and evolutionary biology through physiology and biochemistry to cell and developmental biology. Thale cress is an excellent model since it has a tiny, completely sequenced genome. The plant’s small physical size makes it convenient for growing in vast numbers, while the short life cycle means many generations can be produced in a single year. It sets large quantities of seed and can be routinely transformed to create genetically modified, experimental plants. Importantly, data and genetic information are shared among research groups, while seed and DNA stocks are readily available through international resource centres.

The book is published by Bodleian Library Publishing and can be purchased from the Bodleian Shop.

A day of events to discuss the significance of the dodo took place last Wednesday (18 November).

'The Oxford Dodo: Culture at the Crossroads' was organised by Oxford University’s Museum of Natural History and The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH). It formed part of the national festival of the humanities, Being Human.

It has been covered in more detail in a previous Arts Blog post.

On the day, the winners of a creative writing competition for schoolchildren were announced. More than 170 budding writers between the ages of 7 and 14 entered the contest, coming from 36 schools across the UK.

The competition was judged by children’s author Jasper Fforde, the Story Museum's Co-Director Kim Pickin, the University of Oxford's Knowledge Exchange Champion Kirsten Shepherd-Barr, the Museum of Natural History’s Scott Billings and Hannah Chinnery at Blackwell's.

The winners in the 7-10 age category were:

First place: Rhianna Gorman (age 10, Richard Durning's Endowed Primary School, Lancashire)

Second place: Joel Atkinson (age 9, Pencaitland Primary School, East Lothian)

Joint third place: Frances Watt (age 8, St Aloysius Primary School, Oxford) and Mimi Burrell (age 10, St Andrew's Church of England Primary School, Headington)

The winners in the 11-14 age category were:

First place: Hebe Robertson (age 11, Combe Primary School, Witney)

Second place: Evie Manton (age 11, Oxford Spires Academy)

Third place: Simi Tame (age 12, Perse Upper School Cambridge)

We are delighted to publish the winning entries below. Are you sitting comfortably?

The Last Dodo

By Hebe Robertson, 11, Combe Primary School in Oxfordshire

This is the story of my life, death and the bit afterwards.

The burning summer sun glared on my somewhat unattractive feathers. I was a good old Dodo, to my kind I was known as Dod, I lived on the tropical island of Mauritius. I still reminisce: the days of sunshine, the cool breeze and the gentle lapping of the waves on the white-sand beach. I remember the laughs we had, the parties and the many times I got a feather up my nose. Those were the days.

Then they came, in their indestructible, floating things, they came with sticks that shot death from their handles… They came, wave upon wave, brandishing their weapons. They hunted us down. One by one we were shot and killed. Cousin Frank, Auntie Melina- even my sister, Alice.

I hid in the jungle, shedding silent tears for my loved ones. Already pushing 30, I sat on my ruined nest. I sat and I waited. I, Dod was not going to be hunted like common game; I was going to be remembered as a hero: The Last Dodo.

It was a long night, that night. I, as quiet as a mouse, crept aboard their huge boat and found a box. I pecked my way in with my hemispherical beak and nestled inside. I sniffed.

It was full of my friend’s feathers! I sneezed like a foghorn! Believe it or not- feathers make me sneeze! My noise alerted one enormous man who strode through the open door, opened my box and pulled out his death-stick…

“STOP!” yelled another man, seeing what was happening. He came over to me, stroked my feet. He stared at me: a beaked, clawed, feathered stowaway. He smiled. “I’m a naturalist, don’t be afraid. I’m not going to hurt you,” he said to me. I was allowed to stay on the boat and then, eventually, we began the long journey home.

It took many days and nights. One day, I was woken with a jolt; a bell roared at me to wake up, to rise and shine, but I couldn’t. All the travelling was so unnatural for a dodo that, on arrival, I was scared stiff. After 3 toilsome weeks on a ship: England.

That was over 300 years ago. After that voyage, I lived with that naturalist for 20 years, until I was finally admitted into the glorious kingdom of Dodily, the Dodo God. My life sadly ends here, at the ripe old age of 50, but my legacy lives on.

The naturalist kept me in a glass case in his house and I was passed down through the generations until 1873. That year, the Natural History Museum was built. Exhibits poured in. After a while, the Museum was completely full but the staff there managed to make room for one more: me.

You are welcome to see my bones on show. When you see me, remember my story: The story of The Last Dodo.

Dodo Island

By Rhianna Gorman, Age 10, Richard Durning's Endowed Primary School in Lancashire

Emerging from the mist, I stalked around a tree, my feathers puffed out to protect me from the cold. Leisurely, I walked past a group of tall ferns. All was quiet.

Without warning, a noise I had never heard before gradually got louder. It sounded like the noise meant something, not just a call. The noise increased, I saw a group of giants, but not at all like me. They walked around on something called legs, (as I found out later) and had no feathers on their bodies.

Walking up to them, I could sense something wasn't right. We weren't safe. Then it struck me. I had seen creatures look like this before, thin and pale. They, the things, were hungry. For us, the dodo. Running as fast as I could, I caught a glimpse of an island that I had never seen before. As I reached the shore, I saw my friends staring at it too.

Dragging ourselves desperately, we half-flapped (I knew these wings would come in useful one day), half-swam across to the island. The 'things' were baffled. They couldn't understand where we were heading.

What I now know, which I didn't then, is that our magical island is invisible to the human eye. Over the years, our island drifted further away from the place where the humans live. A full group of us still thrive there now, although we have learnt to live in hiding.

Perhaps one day we will have the courage to leave our island, but whenever we consider it, we hear news of wars and conflicts from migrating birds. That puts us right off. I don't think humans will ever learn to be sensible, and stop killing animals off, like they nearly did to us.

Turns out, that humans think us dodos are dead. That they killed us off. Well, to be frank, they nearly did, they killed thousands of us. All those poor dodos that didn't see or notice the 'hungry' look, and approached rather than fled the humans.

And it's not just us dodos that have been saved by the magic of the island. It has been there to rescue the survivors of many other near extinctions. Today we share our island with great auks and passenger pigeons. We all know how lucky we are to be here and have learnt to be more careful.

I've heard that today's humans aren't so bad after all. They're sad we're no longer there with them. Thinking about it, I'm not sure they will kill many more things, some of them are actually trying to save threatened species.

That doesn't stop them killing other humans though! One day we will probably be discovered. Goodness knows what will happen. Who knows, they might actually help us. But that's unlikely....

They are a common sight off the UK's west coast in summer, but we still have much to learn about the Manx shearwater, a remarkably long-lived Atlantic marine bird.

Ongoing research by Oxford scientists, however, is expanding what we know about the behaviour of the Manx shearwater (also known as Puffinus puffinus – not to be confused with the Atlantic puffin).

Fourth-year Zoology DPhil student Annette Fayet has just completed a piece of research looking at the relative foraging success of young and mature birds.

Annette, who works in the Oxford Navigation Group led by Professor Tim Guilford, said: 'Our project aimed to compare immature (non-breeding) and breeding seabirds, and to answer the question of whether there are any differences in how they forage at sea, including any segregation between them.

'We know very little in general about what immature seabirds do while they're at sea, so there is lots of scope for research and for learning more about their behaviour. The Manx shearwater is no exception to this – and, indeed, they are particularly interesting because they can live for more than 50 years and don't start breeding until they are around five years old.'

The study, published in the journal Animal Behaviour, found that there was substantial segregation between immature and breeding birds on their foraging trips. The young birds also put on less weight during their trips, suggesting they were less successful in finding food.

Annette said: 'We deployed miniature GPS trackers on immature and breeding birds on the large Manx shearwater colony of Skomer, off the Pembrokeshire coast.

'We tracked their foraging trips at sea, which lasted for up to 15 days, and used the GPS data to identify different behaviours at high resolution – for example, when they were flying at speed, foraging, or simply sitting on the water. We also weighed the birds before and after their trips to measure the mass gained during the trip.

'What we found was substantial spatial segregation between younger individuals and breeding birds, while the non-breeding younger birds also gained less mass per unit of time spent foraging, suggesting a lower foraging efficiency.'

The study was one of the first to track immature birds at sea – not an easy task – and the first to directly compare foraging distributions and foraging efficiency between immature and breeding seabirds.

Annette said: 'Our results suggest that immature Manx shearwaters are less efficient when it comes to foraging. They are also foraging in areas with lower productivity than breeders, which we found by looking at data obtained by satellites that estimate how good an area is in terms of resource availability.

'Perhaps they simply need a few years to learn how to forage effectively – we don't think the segregation is a result of aggressive competition by more experienced adult birds. Nor do we think size is an issue, like in other animals, as bigger adult birds are not more efficient than smaller ones.

'It may be that they're not good at finding productive areas, or that the gain of foraging in an area with fewer adults outweighs the cost of foraging in a less productive area.'

Annette added: 'Research like this is important because it addresses central questions in population dynamics, emphasising the role of learning and experience in the life-history tactics of long-lived species.

'It also has important applications for the conservation of these species by identifying important foraging areas, which can help inform future decisions on conservation. These young birds are the next generation of breeders, and we need to learn as much as we can if we want to protect them.'

Today marks 70 years since the first of the Nuremberg trials began.

Dr Jan Lemnitzer, historian at Pembroke College, Oxford University, researches how modern international law was created in the 19th century, how it came to be applied across the globe, and what that meant for international politics.

Here, he writes about the legacy of the Nuremberg trials:

On November 20 1945 the first of the Nuremberg trials began in the main court building of the Bavarian town of Nuremberg with the indictment of 22 of the most senior Nazis that had been captured alive.

Here in the dock were the architects and enforcers of the Holocaust and the Nazi regime’s countless other crimes – among them were Hermann Goering, head of the Luftwaffe and the Nazi rearmament effort; Hans Frank, who had treated Poland like his personal fiefdom and acquired the nickname “the Butcher of Kracow”; Hans Sauckel, who had organised the Nazi slave labour programme.

The trials are widely celebrated as a triumph of law over evil and marking an important turning point in legal history because dealing with the crimes of the Nazis paved the way for justice in the international community in general and the creation of the International Criminal Court in particular. It is this version of the story which has inspired the city of Nuremberg, which also hosted the infamous Nazi party rallies in the 1930s, to launch a new academy to promote the “Nuremberg principles”.

But while Nuremberg is celebrated today, the legal reality is not as clear-cut. As leading international criminal lawyer William Schabas remembers, “when I studied law, in the early 1980s, the Nuremberg Trial was more a curiosity than a model”.

The trials were also plagued by allegations of being little more than victor’s justice. These were made not only by Germans but also by American and British lawyers who felt it was a legal travesty. The judges and prosecutors were not neutral, but came from the four victorious powers – which led to such oddities as a Soviet prosecutor citing the Hitler-Stalin pact as evidence of German aggression against Poland, or a Soviet judge with ample experience of running Stalinist show trials trying to persuade his colleagues that the massacre against Polish officers in Katyn (who had been shot by the Soviets) should be added to the tally of German war crimes.

But the hypocrisy was not exclusive to the Soviet side: the London Charter of August 8 1945 which established the tribunal explicitly limited its remit to war crimes committed by the Axis powers. The tribunal also applied the so-called tu quoque principle which holds that any illegal act was justified if it had also been committed by the enemy (the Latin phrase means “you, too”).

Leading Nazis, Hermann Göring, Karl Dönitz, and Rudolf Hess at Nuremberg. United States Army Signal Corps photographer via Harvard Law Library

No Nazi was charged with terror bombardment since the use of strategic bombardment against civilians had been a pillar of the British and US war efforts. And when US admiral Chester W. Nimitz testified that the US Navy had conducted a campaign of unrestrained submarine warfare against the Japanese from the day after Pearl Harbor, the relevant charges against Admiral Karl Doenitz were quietly dropped.

Wisely, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia dismissed tu quoque as fundamentally flawed.

So why celebrate this trial?

One reason to celebrate Nuremberg is the simple fact that it happened at all. Until just before the end of the war, Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin favoured summary executions of thousands of leading Nazis as the appropriate form of retribution. An outcry among the US public once these plans were leaked was a major factor in laying the road to Nuremberg.

Instead of mass shootings, an old idea from the First World War was revived. The Versailles treaty had compelled Germany to hand over Kaiser Wilhelm II and hundreds of senior officers to an international tribunal to be tried for war crimes. But the Kaiser fled to the Netherlands and the German government refused to hand over any officers or politicians. This time, however, Germany was completely occupied and was unable to resist, so the trials went ahead.

Flawed or not, the Nuremberg tribunal could not have met a more deserving collection of defendants – and it gave them a largely fair trial. Next to 12 death sentences and seven lengthy prison terms, the judgements included three acquittals – one of them for Hans Fritzsche, who had been the regime’s public voice on radio but was not personally involved in planning war crimes.

Crucially, the Nuremberg trials established an irrefutable and detailed record of the Nazi regime’s crimes such as the holocaust at precisely the time when many Germans were eager to forget or claim complete ignorance.

The legacy: important but inconvenient

Today, the most relevant legacy are the “Nuremberg principles”. Confirmed in a UN General Assembly resolution in 1948, they firmly established that individuals can be punished for crimes under international law. Perpetrators could no longer hide behind domestic legislation or the argument that they were merely carrying out orders.

The Nuremberg trials also influenced the Genocide Convention, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Geneva conventions on the laws of war, all signed shortly after the war.

The strongest impact should have been on the development of international criminal law, but this was largely frozen out by the Cold War. With the re-emergence of international tribunals investigating war crimes and genocide in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda in the 1990s, the legacy of Nuremberg proved a powerful argument for establishing the International Criminal Court in 1998.

The Rome Statute includes many principles developed in 1945, so the United States as the main proponent of the Nuremberg trials could take great pride in its impact, were it not for the fact that successive US administrations have fought tooth and nail against the ICC’s insistence that international criminal law might one day be applied against US citizens. So, 70 years later, Nuremberg’s legacy continues to be inconvenient.

This article first appeared in The Conversation.

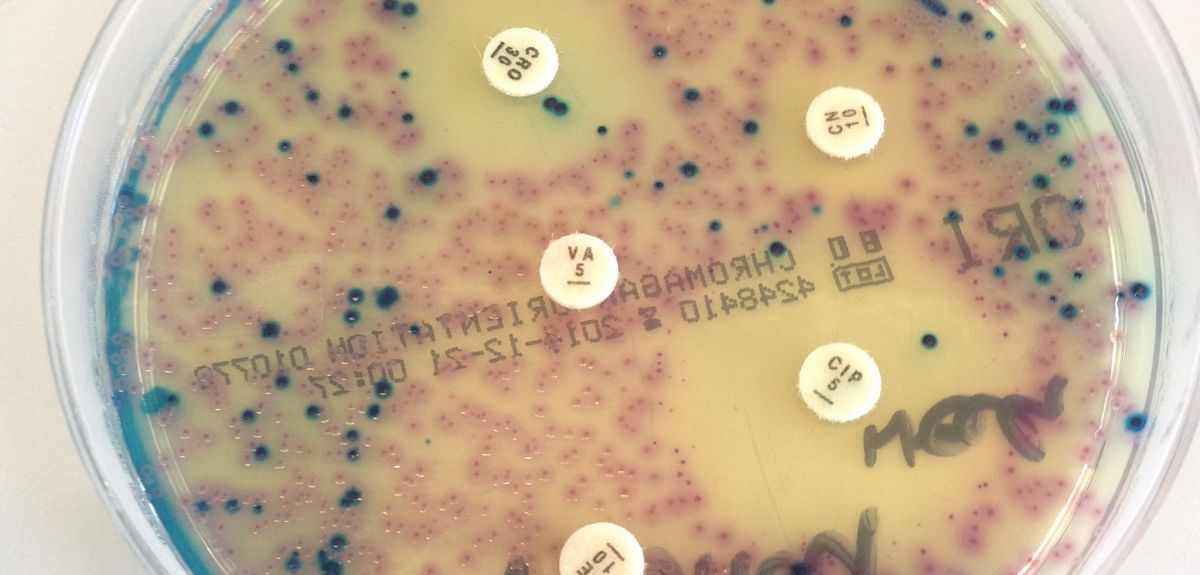

A new computational model helps to find innovative ways to tackle the dangerous problem of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Doctoral student Dan Nichol explains his research.

Antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria are currently causing an annual worldwide death toll totalling hundreds of thousands of lives. A recent report from the Review of Antimicrobial Resistance, commissioned by the government, suggests that this number could reach 10 million by the year 2050. This rapid increase in the rate of antibiotic resistance has been coupled with a drastic slowdown in the discovery of novel antibiotic compounds. It is becoming ever clearer that this crisis cannot be solved simply by discovering novel antibiotics; instead we must find new uses for existing drugs in treating highly-resistant disease.

This crisis cannot be solved simply by discovering novel antibiotics; instead we must find new uses for existing drugs in treating highly-resistant disease.

Traditional medical wisdom is that to effectively treat infections we should prescribe the most effective drugs, at the highest tolerable dose, for as long as is needed to clear the infection. However a new paradigm, known as adaptive therapy, which has emerged from mathematical modelling of the treatment of bacterial infections, viruses and cancer suggests that this strategy may be driving resistance.

By considering disease from the Darwinian perspective, where treatment imposes selective pressure and drives the evolution of resistance, mathematical modelling (coupled with biological experiments and clinical observation) suggests that the optimal treatment strategy may be to prescribe multiple drugs, in sequence or in combination, to pre-empt or exploit evolution.

Using a simple computational model which encodes the population dynamics of an evolving bacterial population as a Markov chain, Daniel Nichol and Jacob Scott have built a tool capable of predicting sequential adaptive therapies for E. coli which reduce, and in many cases entirely prevent, the risk of highly resistant disease emerging.

To design these adaptive therapies it is first necessary to predict how a population of bacteria will evolve. Recently published empirical measures of the fitness landscapes of E. coli under fifteen different antibiotics have made these predictions possible. A fitness landscape is a mapping which assigns to each possible bacterial genotype an associated level of resistance, or fitness, to a given drug. The landscape metaphor, first introduced by Sewell Wright in the 1930s, is a visualisation of this mapping as a surface on which an evolving population ‘climbs’ uphill.

The order in which drugs are given will have a significant impact on the final state after evolution.

By considering the relevant bacterial genotypes as the vertices of a weighted directed graph, where the edge weights encode the probability of a change in the population genotype, this ‘uphill climb’ in the fitness landscape can be reduced to a biased random walk on a graph. By encoding this random walk formally as a Markov chain, the complex process of evolution within a population of bacteria exposed to an antibiotic is reduced to a single matrix multiplication. The immediate consequence of this model is that, as matrix multiplication is non-commutative, the order in which drugs are given will have a significant impact on the final state after evolution. This observation leads to a natural question: are some orderings better than others?

In their work, published in PLOS Computational Biology, Daniel and Jacob show that the answer is ‘yes’. Using the recently published landscapes for E. coli, the research demonstrates that it is possible to prime the disease population using sequences of one to three antibiotics such that resistance to a final antibiotic cannot emerge. This finding suggests a new treatment strategy in fighting antibiotic disease: adaptive therapies which use sequences of drugs to steer, in an evolutionary sense, a disease population to a configuration from which it is both readily treatable but also from which resistance cannot emerge.

As well as demonstrating the possibility of adaptive, sequential therapy for treating highly-resistant bacterial infections, Daniel and Jacob also provide a cautionary warning regarding current clinical practice. When antibiotics are prescribed in sequence, as is often the case in treatment of H pylori, Hepatitis B or the transition from broad to narrow spectrum antibiotics, no guidelines presently exist to specify the order in which drugs should be given. Instead this decision is left to the clinician’s personal preference

Over 70% of drug sequences increase the likelihood of resistance emerging to the final drug when compared to giving that drug alone.

By checking all possible sequences of two, three or four antibiotics for which empirical landscapes are known, the research reveals that the majority, over 70%, of drug sequences increase the likelihood of resistance emerging to the final drug (when compared to giving that drug alone).

In particular, giving Piperacillin+Tazobactam, an antibiotic often used after others fail, as the final drug in a sequence of two or three antibiotics increases the likelihood of resistance arising in over 90% of cases. By giving drugs in arbitrary orders we may be inadvertently encouraging the emergence of antibiotic resistance just as giving drugs with incorrect doses can do so.

To move their theoretical findings towards the clinic, Daniel and Jacob have partnered with microbiologists at the Louis Stokes Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital in Cleveland to perform empirical tests of evolutionary steering. They are also working with Dr Alexander Anderson and Dr Robert Gatenby at the Moffitt Cancer Center, to adapt their model to predicting the effectiveness of cancer therapies.

A major impediment to designing adaptive therapies using their method is that measuring fitness landscapes is a complex problem where the number of strains that need to be synthesised grows exponentially with the number of mutations of interest. Despite this difficulty, empirical fitness landscape research, aided by machine learning techniques which help to reduce the number of strains that need to be synthesised, has grown rapidly in recent years. As this trend continues the potential for therapies exploiting evolutionary steering, and with it the role of computational models in designing treatment, will continue to grow - hopefully enabling better treatment for a variety of deadly diseases in the future.

- ‹ previous

- 138 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?