Features

The Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University has today announced its new director.

Dr Laura Van Broekhoven will take up the directorship on 1 March 2016, following the retirement of Professor Mike O’Hanlon in September.

Dr Van Broekhoven is currently Head of the Curatorial Department and Curator of Middle and South America at the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (encompassing the Tropenmuseum, Volkenkunde and Afrika Museum) in the Netherlands and Assistant Professor of Archaeology at Leiden University.

She said: 'It is both an honour and a delight to be joining the Pitt Rivers Museum. The Museum enjoys the highest reputation internationally for the quality of its curatorial expertise, its extraordinary collections and galleries and as a centre of scholarship.

'This is thanks in particular to the outstanding leadership of Professor O’Hanlon. I am greatly looking forward to working with colleagues in the museum and also with academic colleagues across the University.'

Professor Anne Trefethen, Pro-Vice-Chancellor for the Academic Services and University Collections at Oxford University, said: ‘I am delighted that Dr Van Broekhoven will be joining us at what is a pivotal moment, both for the Pitt Rivers for the University's other museums and collections.

'All of these outstanding collections are now working – individually and collectively – to extend their contribution to the delivery of the University’s strategic aims and I greatly look forward to Dr Broekhoven joining us in this shared endeavour.'

The Pitt Rivers Museum holds one of the world’s finest collections of anthropology and archaeology, from around the world and throughout human history. It welcomes thousands of children from schools in Oxfordshire every year, and carries out world-leading conservation and research in the museum. It is free to visit.

We marvel at their exploits in comic books and on the big screen – but how many of our favourite superheroes' skills and powers have a basis in science?

In a special 'on-screen' edition of The Biochemist, the Biochemical Society's magazine, Professor Fritz Vollrath of Oxford's Department of Zoology attempts to separate the fact from the fiction and explain the mysteries behind the amazing adventures of Spider-Man.

Professor Vollrath, whose research team specialises in the properties of spider silk, writes: 'Seeing Spider-Man swing through New York City tingles the spine and exercises the brain. His ease in making and manipulating gossamer filaments for aerial stunts is truly breath-taking and awe inspiring – which, for materials biologists with decades of experience analysing the stuff, is humbling, to say the least, as totally unforeseen and novel capabilities and capacities emerge.'

Professor Vollrath begins his investigation by explaining the scientific context for Spider-Man's impressive powers, noting that the use of silks by arthropods began approximately 400 million years ago and has undergone significant evolution since then.

Puzzled and impressed by Spider-Man's ability to manufacture vast quantities of silk in the blink of an eye, Professor Vollrath states: 'In-depth analysis of an extensive online database of video imagery, as well as background visual literature (commonly called comic strips), confirms that Spider-Man seems to shoot filaments from the wrist. This immediately raises a number of questions. Firstly, where are the silk glands situated?'

This question is tackled during the course of the article, along with other mysteries such as the immense strength of Spider-Man's silk – as demonstrated in the film Spider-Man 2, in which he uses his web to stop a runaway train.

Professor Vollrath adds: 'It is important to note that Spider-Man, like spiders, has bilateral symmetry – and, in consequence, the ability to produce a double thread. However, unlike spiders, which always produce a double thread (each with the ability to singly hold the animal's weight, as an extra safety feature), Spider-Man more often than not shoots only from one wrist. This behaviour, to me, appears to be highly cavalier.'

And, says Professor Vollrath, Spider-Man's novel technology could have important applications to human industry: 'Unlike spiders, Spider-Man has mutated (or evolved in the relatively short time span of one generation) a spinning system unlike any other found in his spidery lineage.

'This could be important, since Spider-Man's way seems most energy efficient – probably even more so than natural silk spinning, which in itself is 1,000 times more efficient than man's spinning of high-density polyethylene (HDPE).'

It's an impressive set of skills – but, as Professor Vollrath concludes, we may never know the truth: 'I don't think my group will attempt to secure the funding to collect a Spider-Man specimen for study. Instead, we will have to continue to rely for our research on second and third-hand reports and films – which may, of course, have been doctored.'

'I am coming here to listen to you.'

It's an odd comment to hear at the start of what is billed as a talk by the European Commission's senior advisor on innovation. Surely we are there to listen to Robert Madelin, Magdalen College graduate, twenty-two year veteran of the European bureaucracy, currently in the European Political Strategy Centre, the Commission presidency's think tank?

But as the event at Oxford's Department of Pharmacology progresses, it becomes clear that Robert Madelin is a man on a mission. That's literally true: he has been instructed to prepare a report on European and EU member state innovation policy and ask should more or different things be done. And while he is happy to share his views, he also wants to know what the Oxford audience has to say in answer to a few questions.

We will come to those questions in a moment, because with his last five years spent in science, technology and innovation. Mr Madelin's own views should not be discounted – they will doubtless shape the report as much as those of the many people he will consult.

He begins by noting that at a time of profound disruption, none of us know what the future will hold. The answer, he suggests, is not to run for the high ground but to think about how we embrace change while defending our values. In the face of this change, innovation is key:

Wealth in the 21st century depends for Europe on continuing to invent.

Robert Madelin, Senior Adviser for Innovation, European Political Strategy Centre

'The sophistication of our societies, which is what we call civilisation, depends on wealth and wealth in the 21st century depends for Europe on continuing to invent. I also think that inventiveness and innovation are an intrinsic part of Western European civilisation and if we lose the ability to create the new tools for the world as a whole, which Europe has been doing for hundreds of years, it will be a different Europe.'

He says that the way in which we approach innovation is itself changing; innovation now depends on networks far more than previously. Mr Madelin counsels that innovation is at a dangerous stage: is understood enough that people – especially politicians – have grasped the label and use it, but not enough that we have grasped the reality. There are still questions about the size, the shape and the dynamics that best foster innovative networks.

On size and shape, Mr Madelin advises that academics should not be constrained by the boundaries of their discipline – discoveries will come at the crossovers of traditionally separate subjects – or by thinking in terms of individual towns or institutions. Oxford, he notes, is, in global terms, no great distance from London or even Cambridge. To focus solely on the innovation cluster around any one of those towns may be to miss an opportunity.

Yet, it is the dynamics of innovation that most appear to occupy him and it is here he asks his three questions, after beginning with some warnings.

There are fewer instinctive believers than you think

He cautions that just one in five people are instinctive supporters of science research funding. Trying to sell science simply by describing science only works for that 20%. The other 80% need to be convinced.

That affects private funding for science: Mr Madelin observes that there is plenty of money in Europe searching for an investment opportunity but people tend not to invest in things they do not understand. The onus, he adds, is on scientists to make credible and well-presented requests for funding.

If we had twice as much risk capital would inventions happen twice as fast, and if so, what tax and other regimes would help to make that happen?

Is it possible from an invention point of view to argue in favour of a more accommodating regulatory regime?

Robert Madelin, Senior Adviser for Innovation, European Political Strategy Centre

And so his first question is about investment. Noting that – per head – the US and Israel spend around twice what Europe does in terms of risk capital he muses: 'If we had twice as much risk capital would inventions happen twice as fast, and if so, what tax and other regimes would help to make that happen?'

That lack of instinctive support also affects public science policy – not just in terms of funding, but also regulation: 'Is it possible from an invention point of view to argue in favour of a more accommodating regulatory regime?'

A more permissive regime might allow innovations to be used for a period, gauge their impact and then create regulation in response to that, The suggestion seems to be that rather than waiting for regulators to say yes, we should instead create a regulatory environment where new ideas can go ahead until there is a reason to say no. That approach to risk similarly should apply to funding: public funders need to accept failures if they are to fund truly innovative ideas. It is here that the researchers in the audience are most forthright in giving their views – wanting less complexity on the path from discovery to delivery.

Talking to me afterwards, Robert Madelin clearly agrees: 'What I heard there is that it's pretty awful at the moment if you want to get innovation to market. What's standing between us and continued success today is not inventiveness, it's the ability to incentivise and to bring to market in good condition the great stuff we're doing.

'We have a lot to do to become more accommodating so that researchers who invent things get real incentives to acquire their rights to use the IP, to get investment help without too many strings attached, and to get the goods out into the market.'

Citing experiences in the US, Switzerland and Italy, he points to the additional benefit of that approach: 'If you let your inventors invent and you let them profit from their invention they are extremely grateful – they come back with hundreds of millions of pound of gifts to the foundation.'

Everyone has a vote

His final warning is about applications for research funding in the EU. The thirteen most recent members of the EU are all applying for and receiving a declining portion of its science funds. In fact, since 2009, their share has declined by a fifth. While there may be a number of reasons for this, Mr Madelin is concerned that around half the EU appears to be losing faith in science and research.

What is the collective responsibility of universities that are highly successful – such as Oxford – to help lagging regions and universities across the continent to catch up and feel they are potential winners in the innovation game?

Robert Madelin, Senior Adviser for Innovation, European Political Strategy Centre

If you think that just means more research money for everyone else, think again: each of those nations has a vote on the EU budget. If they do not see science funding as having a benefit for them they are more likely to support cuts to the science budget – less research money for everyone.

So the third question is about partnership: 'What is the collective responsibility of universities that are highly successful – such as Oxford – to help lagging regions and universities across the continent to catch up and feel they are potential winners in the innovation game?'

Such mutual support may be better for everyone in the longer term by bringing more people into what he calls the tissue of innovation, and so demonstrating the importance of science to governments and publics.

But as the interview ends, the man with the mission to keep Europe innovating wants to make clear that he is asking the questions because he does not have all the answers:

'I’m only at the beginning of my journey. I can’t lay down the law as to what I think.'

Oxford's Future of Humanity Institute is a leading light in a relatively new and fast-growing area of research: the 'existential risks' that threaten the very existence of humanity in the future.

Its director, Oxford University philosopher Professor Nick Bostrom, is particularly concerned about the dangers of artificial intelligence: once machines become 'smarter' than humans, what impact will that have on us?

Understandably, spreading the word about existential threat is an important aim of the Institute.

So the last fortnight has been a good one: the legendary New Yorker magazine led its most recent issue with a 12,000-word article on Professor Bostrom, and he was named a Global Thinker by Foreign Policy magazine.

'It is good that some more attention is being given to these issues,' said Professor Bostrom. 'There is so much work that needs to be done.'

The Future of Humanity Institute, which was set up by the Oxford Martin School in 2005, is the world's largest research institute working on technical and policy responses to the long-term prospect of smarter-than-human artificial intelligence.

This week saw a further boost to the field, as the Leverhulme Trust gave a £10 million grant for a new research centre to explore the opportunities and challenges to humanity from the development of artificial intelligence.

The Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence is a collaboration between Oxford University, Cambridge University, Imperial College London and University of California Berkeley, involving the Future of Humanity Institute and its parent organisation the Oxford Martin School at Oxford University. The Centre will be physically located at Cambridge University.

Professor Bostrom said: 'We are thrilled about Leverhulme’s decision to support this fledgling field. The funding will enable us to significantly further scale up our own research and strengthen our international collaborations.'

Professor Ian Goldin, Director of the Oxford Martin School, said: 'The Oxford Martin School has been an early supporter of research into the potential long-term impacts of artificial intelligence, and we are pleased to see the field now growing rapidly and gaining international attention and funding.

'The new partnership supported by Leverhulme between the Oxford Martin School, Cambridge University and others will I believe make major strides in addressing a vital issue.'

The underlying principle of radiotherapy is using shaped beams of high energy light or particles to induce cell death in tumour cells, whilst sparing healthy cells. Radiotherapy can be incredibly effective, and is increasingly used in both a curative and palliative capacity to kill or control tumour growth, either alone or in conjunction with chemotherapy. It's a growing method, with up to 60% of cancer patients receiving radiotherapy in the course of treatment.

Oxygen plays a surprisingly large role in tumour evolution and treatment; it is vital for growth and replication of cells. While this might tempt one to think that one can simply starve a tumour of oxygen, this is not the case – oxygen deficient tumours create chaotic networks of blood vessels to sustain themselves, and too frequently acquire a suite of dangerous skills in a low oxygen environment, such as the capacity for metastasis; the spreading of cancer to other parts of the body. Consequently, tumours bereft of oxygen have a markedly worse prognosis, a fact known since the 1950s through research by pioneering medical physicist Hal Gray (see sidebar).

Such is Hal Gray’s influence on the field that his name has been lent not only to the unit of radiation dose the Gray (Gy, Energy per kilogram) but also to the eponymous Gray Institute, which has been based in Oxford since 2008 as part of the Cancer Research UK Oxford centre. Fittingly, the authors of the work here, Dr. David Robert Grimes and Dr. Mike Partridge, are affiliated with the Gray Institute.

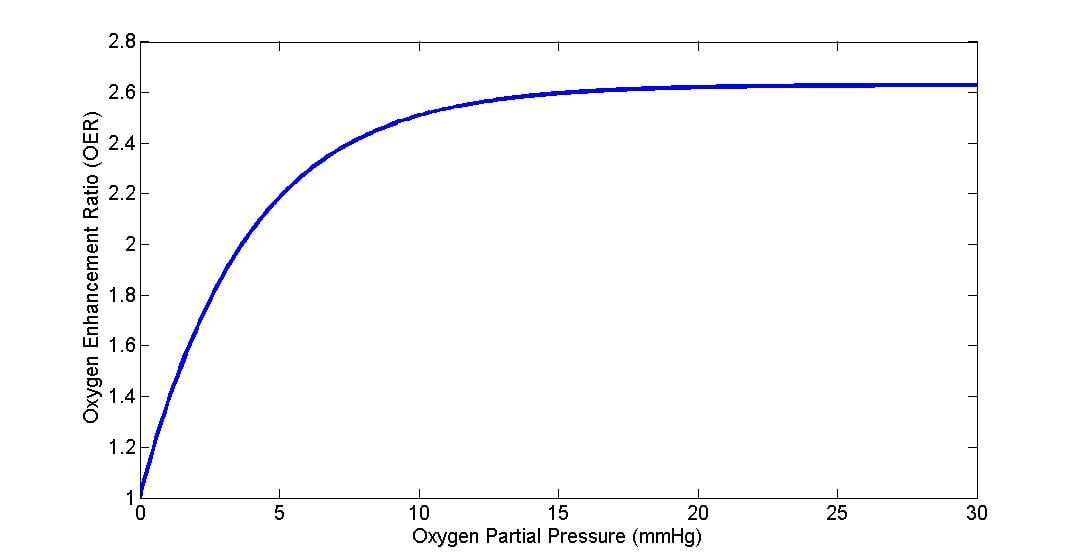

Oxygen plays a substantial role in radiotherapy too, with well oxygenated regions of tumour responding by up to a factor of three better than those segments bereft of oxygen. This effect is known clinically as the Oxygen Enhancement Ratio (OER), and oxygenated tumours prove much easier to treat than their anoxic counterparts. The OER curve (below) is unusual in several respects; instead of increasing linearly, the curve rapidly saturates, obtaining half maximum radio-sensitivity somewhere around an oxygen partial pressure of 3 mmHg with maximum OER typically achieved at partial pressures p > 20 mmHg with subsequent increases not significantly modifying the curve. This distinct curve is seen across all sorts of cells lines with huge variation in biology, from human to yeast and bacteria – suggesting perhaps a chemical culprit behind this useful boost.

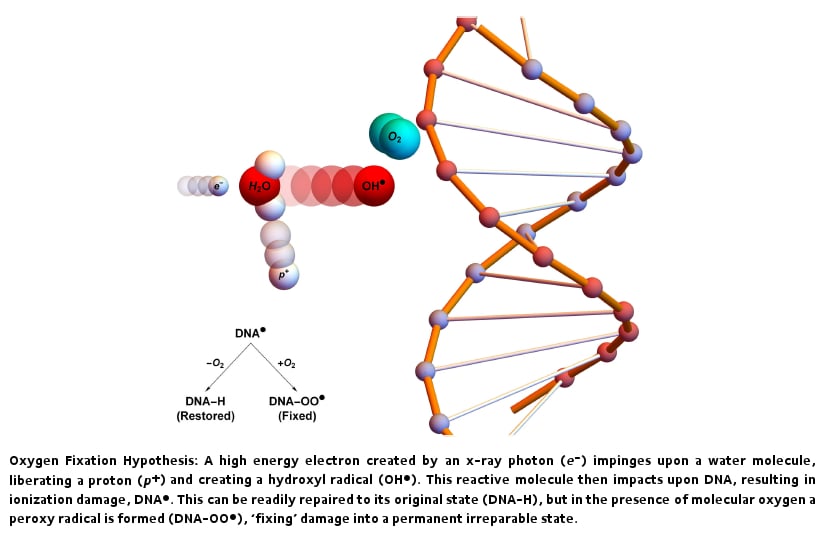

One idea posited to explain this curious result is the oxygen fixation hypothesis. In X-ray therapy, particles of high frequency light are directed at a tumour site. Most of these photons pass through the patient unperturbed, but a significant amount interact with particles in the patient. When a photon does interact, it can create high energy electrons which might impinge upon a target such as the water molecules we contain in abundance. An impacted water molecule loses a proton and becomes a hydroxyl radical. Radicals are highly chemically unstable and extremely reactive - when they encounter DNA, they have the tendency to damage it. This kind of damage is common, and is in general readily chemically repairable, allowing damaged DNA to be restored and cell kill averted. This acts to make radiotherapy less effective, as tumour cells could recover from radiation damage and survive. However, if the radical reacts with oxygen prior to the collision, if forms a new type of radical called a peroxy radical that is difficult or impossible to chemically repair, 'fixing' DNA into a permanent irreparable state. As a consequence, the theory suggests that oxygen is a potent way to make cancers more sensitive to radiotherapy because radical species formed with oxygen are far more difficult for DNA to chemically repair, increasing the lethality of interactions. This concept is illustrated below.

While oxygen fixation is commonly accepted as the mechanism behind the oxygen effect, there has been relatively little work on the fundamental physics underpinning oxygen interaction, nor on the physical parameters that might allow modification of this effect. Up until now, mathematical descriptions of OER have tended to be phenomenological and empirical, capturing the gross behaviour of the curve but not the underlying mechanisms that make it so. This is of course useful, but leaves much unanswered. This curious unknown captured the attention of my colleague Dr Mike Partridge and myself. Indeed, it seemed especially relevant to us, as physicists at Oxford have been working on ways to improve the effectiveness of radiotherapy through a wide variety of methods, including studying the role of oxygen in both cancer prognosis and treatment. We ourselves have published quite a bit on oxygen dynamics before [1,2] , and given the importance of radiotherapy in modern cancer treatment, we were intrigued by not only what factors influence OER but also what parameters might be varied to better understand this oxygen boost to treatment efficacy.

In our new paper published in the Institute of Physics journal Biomedical Physics and Engineering Express [3], we explore the origins of the oxygen effect , describing and predicting the OER curve from first principles. This work establishes a mechanistic explanation of the OER curve from physical first principle, and helps shed light on all the fascinating processes that lead to this marked effect. Our model combines a range of physical considerations from statistical mechanics and kinetic theory, from the thermal velocity and mean-free path length of oxygen molecules to the interaction probability of radicals and DNA. This model was compared to classic experiments on the oxygen enhancement effects, and the results found to agree well with observed experimental data. The conclusions of this work strongly support the idea that oxygen fixation with radicals is indeed the mechanism which gives rise to the observed clinical effect. Our theory also suggests that while most of the vital parameters are fixed constants of nature and impossible to modify, there is a small thermal effect which may exist, though it is not likely to be clinically exploitable.

Understanding the mechanisms that affect treatment outcome are of paramount importance in improving patient prognosis, and the better we understand the factors that influence treatment outcome the better we can treat patients and improve lives.

- ‹ previous

- 136 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?