Features

We've been able to see them for over a hundred years, but only now are scientists beginning to get to the bottom of what's happening inside membraneless organelles – compartments within cells that really do have no boundaries.

Most people will be broadly familiar with cellular structures such as the nucleus or mitochondria. These compartments, or organelles, are bounded by biological membranes to separate them from the rest of the cell. But, as the name suggests, the droplets of liquid protein known as membraneless organelles have no such physical border, making them an intriguing subject for scientists keen to make use of the advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques that have opened up their inner workings in the past five years.

And now, an Oxford University-led study published in the journal Nature Chemistry has shed new light on the phenomenon, demonstrating that even stable structures such as the DNA double helix can be altered, or 'melted', inside these droplets. That’s in addition to their ability to separate molecules such as proteins that reside within the organelles.

The work also has huge commercial potential, with Oxford's technology transfer company having filed a patent on a technique that could lead to a revolutionary platform for purifying biomolecules in life sciences research.

First author Dr Timothy Nott of Oxford's Department of Chemistry says: 'The premise of our work has been trying to understand how cells are internally compartmentalised. Broadly speaking, there are two ways of creating compartments in cells: one using membranes, which produces things like the nucleus or mitochondria, and another without membranes.

'These membraneless organelles were first observed at the turn of the last century, when experiments involving sea urchin eggs being "squashed" produced globules of liquid that fused together and behaved like an emulsion.

'In the past five years, scientists have realised that advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques can be used to carry out rapid live cell imaging with the aim of interrogating the physical behaviour of these droplets in cells. So only recently have we developed the toolkit necessary to analyse what's going on.'

While there are different classes of membraneless organelles within cells, they all share the common feature of this lack of a delimiting boundary. As well as being tiny and spherical, they also have the viscosity of honey and have been likened to globules of oil in vinegar.

Dr Nott says: 'These unusual properties make membraneless organelles difficult to study. You can't just purify them from within the cell and expect them to behave the same way on the outside.

'What we've been doing is trying to reconstitute them in the lab, controlling when and how they form and performing a wide range of experiments on them.'

The team has been able to identify the main protein components of membraneless organelles – they are made up of long protein chains that 'behave like spaghetti' – which can then be targeted and purified in the lab.

Professor Andrew Baldwin, group leader in Oxford's Department of Chemistry, adds: 'Francis Crick used to say that if you want to study function, study structure. But what we find with membraneless organelles is that while they don't really have a structure, they have plenty of functions.'

Oxford University's technology transfer company is keen to hear from parties interested in developing this innovative technology ([email protected]).

It can take some time before anti-depressant drugs have an effect on people. Yet, the chemical changes that they cause in the brain happen quite rapidly. Understanding this paradox could enable us to create more effective treatments for depression.

In addition to the direct chemical effect, the drug seems to contribute to learning to be in control.

Professor Robin Murphy, Department of Experimental Psychology

However, new research from a group of scientists at Oxford, Harvard and Limerick universities has shown that the way the drugs affect learning about control and helplessness may explain both why anti-depressant effects take time and why their effectiveness differs across individuals.

The team's study saw them administer a commonly prescribed dosage of an anti-depressant drug for 7 days to people who were depressed or not depressed. The drug, escitalopram, increases levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the central nervous system.

After 7 days of either taking the drug or a placebo, volunteers took part in a computer-based game designed to test learning ability. They were required to learn about how their actions could control events occurring in the game. Volunteers tested the effectiveness of their actions on numerous occasions (using keyboard presses) to check if they could control a sound turning on. The researchers had ensured that, in all cases, the volunteers actually had no control over these events in the game.

In these situations, healthy people who are not experiencing depression tend to perceive that they are 'in control', whereas people with depression report little control or so-called helplessness. In this study, published in the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, the team found that the anti-depressant drug affected how people behaved in the game, and importantly how they learned about their own control over events in relation to events randomly occurring in the environment.

People with depression who were taking the placebo tended to interact less with the game and feel that the environment was more in control of events than they were. After taking the drug for 7 days, depressed volunteers interacted more with the game, testing whether their actions controlled the situation on more occasions, and the environment was judged as less controlling than for participants on the placebo. In other words, the drug influenced depressions' effects on learning about control.

Professor Robin Murphy said: 'Other research from members of our group has emphasized the effects these drugs have on processing of emotions, here we focussed on our sense of agency, on how we learn to be 'in control'. In addition to the direct chemical effect, the drug seems to contribute to learning to be in control, less constrained by the environment, and perhaps this might be a link to how these drugs contribute to the alleviation of depression.'

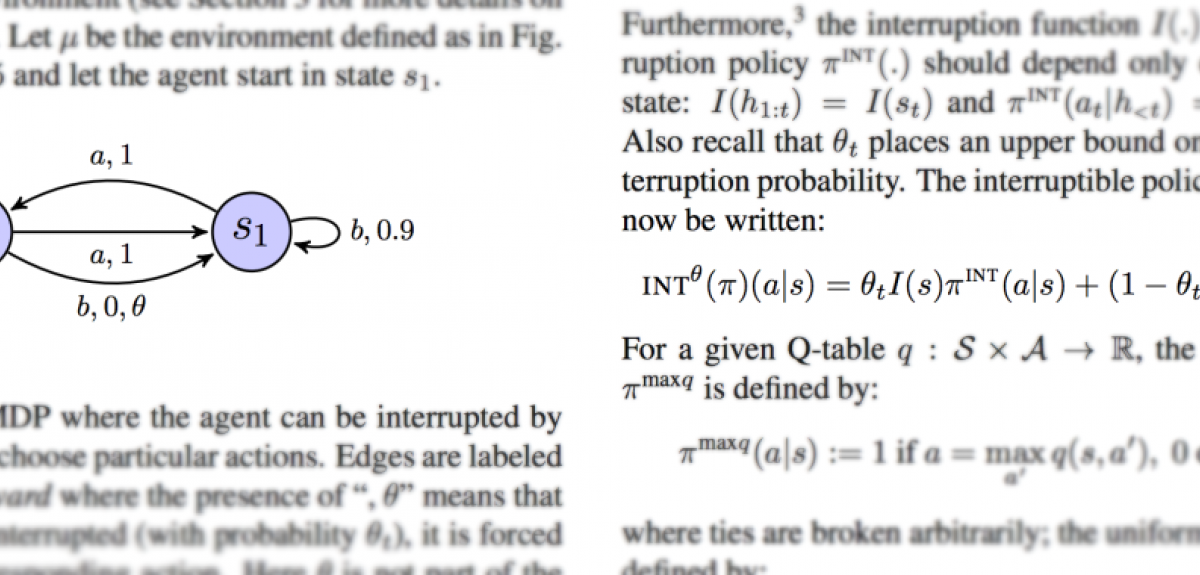

Oxford academics are teaming up with Google DeepMind to make artificial intelligence safer.

Laurent Orseau, of Google DeepMind, and Stuart Armstrong, the Alexander Tamas Fellow in Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning at the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, will be presenting their research on reinforcement learning agent interruptibility at the Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence conference in New York City later this month.

Orseau and Armstrong's research explores a method to ensure that reinforcement learning agents can be repeatedly safely interrupted by human or automatic overseers. This ensures that the agents do not “learn” about these interruptions, and do not take steps to avoid or manipulate the interruptions.

The researchers say: 'Safe interruptibility can be useful to take control of a robot that is misbehaving… take it out of a delicate situation, or even to temporarily use it to achieve a task it did not learn to perform.'

Laurent Orseau of Google DeepMind says: 'This collaboration is one of the first steps toward AI Safety research, and there's no doubt FHI and Google DeepMind will work again together to make AI safer.'

A more detailed story can be found on the FHI website and the full paper can be downloaded here.

This is a guest post by Mary Cruse, science writer at Diamond Light Source.

All over the world, engineers are beset by a niggling problem: when materials get hot, they expand.

Why is this such an issue? Well, because materials get hot all the time. Think about aeroplanes, buildings, bridges or virtually any kind of technology.

When you expose any of these materials to energy – whether that energy comes from the sun, fuel burning in an engine or from an electric current – they're going to get bigger, and in some cases that can cause them to fail.

Whether it's a case of seasonal cracks in the road surface or a short-circuited smart phone, thermal expansion can be the bane of an engineer's existence.

But thanks to Oxford University scientists, heat-related failure could ultimately become a thing of the past.

Not all materials expand when they get hot. These so-called 'negative thermal expansion' - or NTE – materials actually contract when heated.

But scientists have never been able to control this process. The material might shrink too far or not far enough. Without being able to modulate this contraction, we just can't harness the potential of NTE materials.

However, research announced this week could change all that. A group led by Dr Mark Senn of Oxford's Department of Chemistry has successfully developed a way of manipulating a class of materials into expanding or contracting at will.

The international collaboration, made up of scientists from Oxford, Imperial, Diamond Light Source and institutions in Korea and the US, haa hit upon a potentially revolutionary finding.

NTE is caused by atoms vibrating inside a material – these vibrations cause the atoms to move closer together. In the past, we haven't been able to control how much closer the atoms became or how quickly the process takes place.

But the work of Dr Senn and his group has revealed that it's possible to manipulate this effect in a perovskite material by changing the concentration of two key elements: strontium and calcium.

The group found that changing these two elements proved to be the key to harnessing the power of NTE in the perovskite they were studying. And if we can control that expansion and contraction, then we have a powerful new resource for engineering technology and infrastructure.

This is an early step forwards, but the findings of the Senn group have opened the door for other researchers looking to control NTE materials. We know that adjusting the elemental composition of this perovskite works: it may be that the same method could work for other materials.

Dr Senn explained the impact of the work: 'This is hugely exciting because we now have a "chemical recipe" for controlling the expansion and contraction of the material when heated. This should prove to have much wider applications.'

Dr Claire Murray is a support scientist at Diamond Light Source. Her expertise in synchrotron science allowed the group to scrutinise the very small changes on the atomic length scale occurring in the perovskite as its composition changed.

She said: 'Researchers are increasingly turning to synchrotrons like Diamond to deepen their understanding of chemical processes and, in a similar way to chefs adjusting their recipes to get a better texture or taste, scientists are adjusting the elemental composition of materials, and thereby controlling their properties and functions in ways that will bring performance and safety benefits in a wide range of areas including transport, construction and new technology.'

There may be some way to go before we start seeing NTE materials in our phones and aeroplanes, but we now know how to control this material, and that's a major step forward.

The laws of physics may sometimes be stacked against engineers, forcing them to design products that account for uncontrollable expansions and contractions, but research like this gives us just that little bit more control.

And when it comes to engineering our everyday lives – from transport to technology – that can make all the difference.

This blog post is adapted from an article published by the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research.

Plants use many strategies to disperse their seeds, but among the most fascinating are exploding seed pods. Scientists had assumed that the energy to power these explosions was generated through the seed pods deforming as they dried out, but in the case of 'popping cress' (Cardamine hirsuta – a common garden weed) this turns out not to be the case. A new paper by an international group of researchers, published in the journal Cell, offers new insights into the biology and mechanics behind this process.

Several teams of scientists spanning different disciplines and countries, including Oxford mathematicians Alain Goriely and Derek Moulton, along with colleagues from Oxford's departments of Plant Sciences, Zoology and Engineering, worked together to discover how the seed pods of popping cress explode. A rapid movement like this is rare among plants: since plants do not have muscles, most movements in the plant kingdom are extremely slow. However, the explosive shatter of popping cress pods is so fast – an acceleration from 0 to 10 metres per second in about half a millisecond – that advanced high-speed cameras are required to see it.

The scientists, led by Angela Hay, a plant geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research, discovered that the secret to explosive acceleration in popping cress is the evolutionary innovation of a fruit wall that can store elastic energy through growth and expansion and can rapidly release this energy at the right stage of development.

Previously, scientists had claimed that tension was generated by differential contraction of the inner and outer layers of the seed pod as it dried. So what puzzled the authors of the Cell paper was how popping cress pods explode while green and hydrated, rather than brown and dry. Their surprising discovery was that hydrated cells in the outer layer of the seed pod actually use their internal pressure in order to contract and generate tension.

The authors used a computational model of three-dimensional plant cells to show that when these cells are pressurized, they expand in depth while contracting in length – much like an air mattress does when inflated.

Another unexpected finding was an evolutionary novelty explaining how this energy is released. The authors found that the fruit wall seeks to coil along its length to release tension but is prevented from doing so by its curved cross-section. Professor Moulton said: 'This geometric constraint is also found in a toy called a slap bracelet. In both the toy and the seed pod, the cross-section first has to flatten before the tension is suddenly released by coiling.' Unexpectedly, this mechanism relies on a unique cell wall geometry in the seed pod. Professor Moulton added: 'This wall is shaped like a hinge, which can open, causing the fruit wall to flatten in cross-section and explosively coil.'

Emphasising the multidisciplinary, collaborative approach to this paper, Professor Goriely said: 'This approach was only made possible by combining state-of-the-art modelling techniques with biophysical measurements and biological experiments.'

- ‹ previous

- 124 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?