Features

Think of 'an academic' and your stereotype may well include a tendency to wordiness. In truth, while some may live up to that image, academic presentation is usually about distilling information rather than padding it.

Even so, summing up your entire doctorate in three minutes is a challenge. That's about 400 - 500 words, compared to the 80,000 word limit for a doctoral thesis (this blog intro is 185 - or something over a minute). Yet, that's the challenge of the 3 Minute Thesis (3MT), a competition originally developed by The University of Queensland. It aims to cultivate students' academic, presentation, and research communication skills. The competition supports their capacity to effectively explain their research in three minutes, in a language appropriate to a non-specialist audience.

Recently, seven doctoral students from across the University of Oxford competed in the University's 3MT final. Both the winner and runner-up were from Oxford's Medical Sciences Division: Lien Davidson and Tomasz Dobrzycki.

Below, you'll find the 3 Minute Thesis of Lien Davidson, a DPhil candidate in the Institute of Reproductive Sciences, part of the Nuffield Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. We'll publish Tomasz's 3MT later this week.

Lien Davidson: Embryos and Lasers

Some of you may have heard of the name Louise Brown, she was the first test tube baby, or in vitro fertilisation baby, and she was born right here in the UK. What some of you might not know is that in vitro fertilisation, or IVF, isn't only for couples who are infertile.

Embryo biopsy has been performed all over the world and healthy babies have been born, but how safe is this technique really at the time the hole is being drilled? There's no standardisation or detailed safety investigations of how the hole should be created, and every clinic does it differently.

Lien Davidson, Institute of Reproductive Sciences

But why would a fertile couple want to go through the complicated and expensive procedure of IVF? Well the answer to that question is: hereditary genetic disease. A couple with a genetic disease is able to use IVF to produce genetically healthy children.

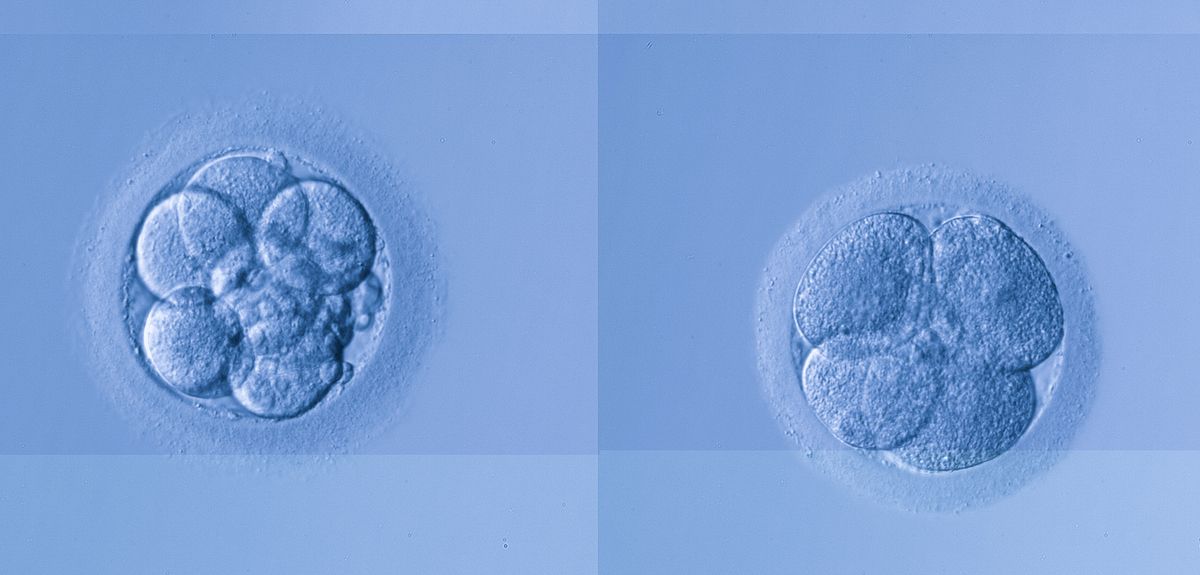

This is done through a process called 'Embryo biopsy'. You take a sperm from the man, an egg from the woman, and you fertilise them together in the lab to create an embryo. This embryo divides into 2 cells, 4 cells, 8 cells, and so on, and at this early stage every single cell in the embryo is perfectly identical. What we know as scientists is that at this early stage, you can remove one of these cells from the embryo and the rest will continue to grow on healthily. And with this one cell you can test the entire genome of that whole embryo. That way, you can choose an embryo that's free of the genetic disease, and place that one back into the mother's uterus.

So, how do you get this cell out for testing? It's an extremely delicate and fragile procedure, because embryos at this stage have a protective shell around them, much like that of a chicken's egg, and this needs to be breached. Currently in clinics this can be done by drilling a small hole using a laser pulse, and that's where my research comes in, I research the safety of these lasers on embryos.

Embryo biopsy has been performed all over the world and healthy babies have been born, but how safe is this technique really at the time the hole is being drilled? There's no standardisation or detailed safety investigations of how the hole should be created, and every clinic does it differently.

So to investigate the safety of these lasers on embryos I use a mouse model, which looks and grows the same way as a human embryo in these early days. I'm testing different holes sizes, laser powers, and hole locations in the shell to see if there are any damaging effects that we might not know about yet. Results so far at the halfway point of my thesis have found there are certain laser treatments which appear safe for use in the embryos, and others which appear damaging in terms of the quality of the DNA and the embryo's metabolism. I’m currently looking to see if there are any minor changes in important developmental genes which could be having negative effects.

My goal for the future is to find safe laser parameters for standardisation in the clinic, and to highlight other damaging parameters that should be avoided altogether. Given that these procedures are used to literally create healthy life, the safety of each step is of the utmost importance, and with the continuation of studies such as these, we can have the peace of mind of knowing that these techniques are not damaging the precious lives that are being created.

A ten-part BBC drama focusing on the court of Louis XIV at the Palace of Versailles is underway.

The Daily Telegraph calls it "the BBC's new steamy period drama", though its co-creator David Wolstencroft has higher ambitions for the programme.

'Sometimes it takes a different context to shine a light on history,' he says.

Dr Alison Oliver, research editor at the Voltaire Foundation at Oxford University, gives Arts Blog a scholarly take on the new series:

‘Louis XIV was so magnificent in his court, as well as reign, that the least particulars of his private life seem to interest posterity.’

So wrote Voltaire in his account of the reign of Louis XIV, published in 1751. It’s still true today, apparently – a bit of a fuss has been made in the past few weeks about a BBC drama series called Versailles. Set during the reign of the French Sun King and controversially made in English, it seems to be aimed at the audience for the historical romp genre (The Tudors, Rome), with plenty of see-through dresses and glossy hair.

The show itself seems to be pretty much what you’d expect from the genre. Every lurid allegation of life at court which has surfaced over the past 300-odd years has been trussed up and ornamented, to choruses of ‘for shame!’ from the Daily Mail, while familiar faces on the media history circuit are produced to give academic credibility to every unlikely-sounding anecdote. An affair between the king and his sister-in-law? His brother’s homosexuality and transvestism? Queen Marie-Thérèse, famous for her Catholic piety and lack of interest in carnality, giving birth to a dark-skinned, apparently illegitimate baby?

The programme makers are playing a mischievous game with us: simultaneously wanting us to gasp in horror while reassuring us of their interest in historical veracity. No need to bother with plausibility, then – (alleged) truth despite its implausibility is the trump card here.

We have a rich supply of this gossip, partly because of the success of Louis XIV at keeping his nobility within the confines of his enormous palace at Versailles. Quite a few of them kept almost daily diaries detailing who was rumoured to be sleeping with whom, pregnancies, illnesses, squabbles…

Voltaire included several chapters of anecdotes in his Age of Louis XIV, which he introduces with the observation: ‘We had rather be informed of what passed in the cabinet of Augustus, than hear a full detail of the conquests of Attila or Tamerlane.’ And who wouldn’t? Voltaire’s chapters of anecdotes represent the private history of the king and his entourage as people, in contrast to the previous twenty-four chapters of public events: wars won and lost, peace treaties, alliances and so on.

Voltaire deliberately carves out a space in his monumental history of the reign for these ‘domestic details’, but he also warns the reader to weigh up the sources when deciding when something is true or not. Although he admits that they are ‘sure to engage public attention’, in a later edition he adds a marginal note at this point: ‘Beware of anecdotes’.

The real domestic details are ultimately unknowable, of course, but anyone can and does imagine what might have happened in a bedroom, a birthing chamber, a salon.

The temptation to fill in the gaps and invite a 21st century audience to experience this private space in simulation is, I think, what has proved so tantalising both to the creative impulses of the script-writers and the voyeuristic ones of the audience.

These striking works of art have been created by Oxford students and will be on display in the city when the annual Ruskin Degree Show opens tomorrow.

RUSKIN.SHOW will be the first degree show held in the new studios on Bullingdon Road.

It is also the first degree show featuring the work of undergraduate finalists and the new intake on the Master of Fine Art course at the Ruskin School.

The degree show will be open from Saturday 18 June until Wednesday 22 June, 12pm-6pm. It will be held at The Ruskin School of Art's new building at 128 Bullingdon Road.

For more information, visit the Ruskin School of Art's website.

By Alvin Ong

By Alvin Ong By Mirren Kessling

By Mirren KesslingSome of the UK's top female scientists will be taking to their soapboxes in Oxford this weekend to share their passion for their subjects with the public.

This Saturday, 18 June, the national Soapbox Science initiative will be making its debut in Oxford. From 2pm to 5pm in Cornmarket Street, 12 female scientists from across the country will be giving a series of fascinating talks on topics as diverse as facial recognition, oral health, the body clock, saving elephants in Mali, and even what tea bags can tell us about soil.

Now in its sixth year, Soapbox Science aims to challenge perceptions of who a scientist is by celebrating the diverse backgrounds of women in science. With speakers ranging from PhD students to professors, Soapbox Science represents the full spectrum of the academic career path and gives the speakers themselves the chance to meet and network with other women in science.

The talks are free and open to the public, and anyone stopping by can expect hands-on props, experiments and specimens, as well as bags of enthusiasm from the speakers.

Carlyn Samuel, ICCS Research Coordinator in the Department of Zoology at Oxford, is coordinating the Oxford leg of Soapbox Science. She said: 'Being part of the great team that has brought Soapbox Science to Oxford for the first time has been an amazing experience. It has opened my eyes to some really interesting research that I would never have heard about otherwise, and I am sure visitors to Cornmarket Street this Saturday will agree.

'Our aim is to bring cutting-edge science to the public in an accessible, fun and unintimidating way. We're hoping to inspire people who never normally get exposed to science – particularly young people. I'm excited that there is such a wide range of topics to learn about, from contentious issues like nuclear energy to saving desert elephants or finding out how chemists have much to learn from nature.'

Among those representing Oxford University on Saturday will be Dr Susan Canney, from the Department of Zoology, whose work involves assessing the threats facing elephants in Mali, and Dr Irina Velsko, from the School of Archaeology, who studies ancient dental calculus and will be talking about how the bacteria that live in our mouths can have a big impact on our overall health.

Soapbox Science co-founder, Dr Nathalie Pettorelli of the Zoological Society of London, said: 'Soapbox Science gives female scientists the much-needed boost to their visibility and profile they need to help achieve equality in science. In the five years of Soapbox, we have seen real impact on the career paths of our speakers, raising their profiles and opening new opportunities for them within the science communities.'

With Johnny Depp’s ‘Mad Hatter’ returning to cinemas in Disney's ‘Through the Looking Glass’, an Oxford academic reveals the real-life influences on Lewis Carroll’s portrayal of insanity and the insane in his Alice books.

Franziska E. Kohlt of the Faculty of English Language and Literature explores Carroll’s knowledge of Victorian psychiatry in the current issue of the Journal of Victorian Culture.

She explains that Carroll’s close relationship with his uncle, Commissioner in Lunacy Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge, was his primary connection to the profession. A well-connected barrister, Skeffington was responsible for inspecting lunatic asylums; many of his psychiatric colleagues became friends of Carroll’s too.

Skeffington also had a keen interest in photography, which he passed on to Carroll. It was through this hobby that Carroll came into contact with a friend of his uncle’s, Dr Hugh Welch Diamond of the Surrey lunatic asylum, who believed that photography had an important role to play in diagnosing and recording mental illness. According to contemporary theories, the state of one’s mind was reflected in one’s appearance – which made photographs a highly useful tool.

Ms Kohlt writes: 'Carroll's engagement with Diamond’s work illustrates how the influence of Skeffington and his profession were multifaceted in their nature and consequently found their way into his nephew’s writing via indirect routes. It further indicates how Skeffington’s professional contacts provided Carroll with the opportunity to witness professional practices first hand.'

Through his contacts, Carroll developed an understanding of the practical aspects of psychiatric practice. The Mad Tea-Party in Alice’s Adventures was inspired directly by the tea parties held in asylums as ‘therapeutic entertainments.’ ‘That the types of insanity of the tea-party’s members draw on popular imagery of insanity is made explicit at the earliest instance when the Cheshire Cat informs Alice they are ‘both mad’,’ she writes.

Carroll was also very aware of the class and wealth distinctions between ‘lunatics’ and ‘pauper lunatics,’ which had so much bearing on where and how a Victorian patient was treated. Though never actually referred to in the novel as ‘the mad hatter’, Ms Kohlt feels the character ‘illustrates vividly’ the case of a typical pauper lunatic.

'Carroll's Hatter is consistent with Victorian asylum environments in other aspects, as impoverished hatters and other manual workers and artisans were frequently to be found among a pauper lunatic asylum’s population,' she says.

Ms Kohlt says writers and satirists like Carroll played an important role in raising public awareness of psychiatry. They also shaped the popular image of insanity through their plots and characters.

She says Alice is far more than just a children's novel. 'Alice stands in dialogue with both psychiatric practice and popular perceptions of insanity,' she says.

Follow Franziska Kohlt on Twitter.

- ‹ previous

- 123 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?