Features

Many academics have recently come back to Oxford after a summer holiday. But Professor Liz Frood’s return to work (part-time) as Professor of Egyptology last week is a much more remarkable story.

Professor Frood contracted sepsis in August 2015. Her cousin Jane Wynyard picks up the story: ‘She spent ten days in the ICU, five months in hospital, had her legs amputated below the knees, lost her hearing in one ear, her nose collapsed and her hands were damaged almost beyond repair,’ she says.

This left Professor Frood severely disabled, with both legs amputated, no dexterity in my hands, partial deafness, and a reconstructed nose.

Miss Wynyard adds: 'Before Liz’s illness, none of our family had ever heard of sepsis or understood the life-changing and devastating effects this terrible infection could have.

‘In just one year, Liz has totally inspired and humbled us with her amazing will to survive and courageous battle to live a normal life despite her terrible injuries. Her bravery and determination have been matched by the incredible work of the NHS staff, doctors, surgeons and specialists whom we will always be indebted to for saving Liz.’

Some of Professor Frood’s family and friends set off today (Friday 9 September) on a bike ride beginning at the Ashmolean Museum and due to end in Cardiff. They are due to arrive in Gloucester this evening after completing the arduous first stage of their trip.

‘It’s been brilliant so far,’ Professor Frood reports. ‘We had a great send-off! The cyclists have been riding through gorgeous countryside, which seems to have them all very excited.’

The team, called the Dons of Oxford, hopes to raise awareness of sepsis and to raise money for the UK Sepsis Trust. They would welcome donations here.

A little over a year ago, Professor David Macdonald of Oxford University's Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) spoke of his desire to harness the global interest in the killing of Cecil the lion, creating a movement rather than simply a moment.

That journey continues this week with the Cecil Summit, a workshop held in Oxford that will bring together leading figures from across the world to consider future initiatives to preserve the African lion.

The summit will culminate in a free public event on Wednesday 7 September at the Blavatnik School of Government in which anyone interested in conservation will be able to hear the thoughts of top lion experts, as well as a variety of innovative thinkers from fields as diverse as economics, development, international relations and ethics.

The discussion, to be introduced with an illustrated talk by Professor Macdonald, will be chaired by Alan Rusbridger, Principal of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford and former editor of The Guardian. It will take place from 5pm to 7pm. The summit follows more than a year of sustained interest in the story of Cecil, who was killed by a big game hunter outside Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe on 2 July 2015. Researchers from WildCRU were studying and tracking Cecil and his pride as part of their lion conservation research.

Professor Macdonald, the founding Director of WildCRU, explained the context for the summit: 'Lions, arguably the most iconic species in the world, are doing badly. That understatement captures the shocking fact that wild lions nowadays roam in only 8% of their historic range. Last year, researchers from WildCRU and Panthera, the big cat charity based in New York, published the finding that whereas a hundred years ago it is widely thought there were about 200,000 lions, today there are closer to 20,000.

'Against this distressing but widely ignored background, suddenly everything changed with the killing of Cecil, a fascinating elderly male Zimbabwean lion that WildCRU had been satellite tracking since 2008. Cecil's death prompted unprecedented media interest globally, and so with the world's attention focused on lions, WildCRU and Panthera resolved to hold the Cecil Summit with the purpose of asking whether the morbid trajectory of the lion's fate could be reversed, breaking the mould of conservation by seeking new, innovative approaches from beyond the realms of dedicated field biologists.'

The summit is a joint venture between Oxford and Panthera, whose President Luke Hunter said: 'The tragedy of Cecil's death spurred a unique sea change moment for global awareness of the lion's precarious state. But over a year later, the species is still in freefall in many places. The lion is running out of time.

'We hope that the Cecil Summit's brain trust of conservationists and innovators can spur a new infusion of support for African governments and people working to save the magnificent African lion.'

Speaking from WildCRU's centre at Tubney House near Oxford, Professor Macdonald said: 'In my experience, this summit is unique: we take 30 innovative minds, present them with a new problem, mix them with some conservation specialists, shake and stir, and hope for a breakthrough. It may work, it may not, but at least we will have tried. We'll have grasped the unique Cecil moment and challenged ourselves to find a new way ahead for the Cecil movement.

'Perhaps the unique feature of our approach, forcing inter-disciplinarity between those who know about lions and those who know about delivering high-level change to the human enterprise, will itself become a way ahead in conservation: the Tubney Format!'

He added: 'We believe that the more brains are involved the better, which is why we've arranged a public session in which Alan Rusbridger will lead a conversation with such guests as Rory Stewart, the UK's Minister for International Development; Achim Steiner, Director of the Oxford Martin School and recently head of the United Nations Environment Programme; Wilson Mutinhima, the Director General of Zimbabwe's National Parks; Craig Packer, the world's leading lion biologist; and Tom Kaplan, WildCRU's patron and the greatest benefactor in history to big cat conservation.'

The Cecil Summit's public event will take place at the Blavatnik School of Government from 5pm UK time on Wednesday 7 September. Attendance is free, but booking is required via the Oxford University website. The event will also be live-streamed on WildCRU's YouTube channel.

Oxford academics have teamed-up with an animator to bring ancient Greek vase scenes to life.

The images on this 2,500-year-old vase have been animated to show what life was like in ancient Greece.

The Classics in Communities project, which is led by Mai Musié of Oxford University to encourage the teaching of ancient languages like Latin and Greek, has teamed up with the Panoply Vase Animation Project following an award from the Oxford University Knowledge Exchange Fund.

The animation is freely available to watch online, and its creators hope it is used by teachers and lecturers to support their teaching of topics related to ancient Greece.

The video can be viewed here.

'Our animation features a cup that would once have been used at ancient drinking parties 2,500 years ago,' says Dr Sonya Nevin, co-director of the Panoply Vase Animation Project.

'The cup's decoration comes to life in the animation, with a scene of drinking, chatting, and playing music and games now acted out before your eyes.

'We hope it will be used by teachers, students and anyone else who has an interest in seeing classical history brought to life.'

The project is the latest initiative by Classics in Communities, a project involving Oxford University, the Iris Project, and Cambridge University.

'Our aim is to promote the teaching of Latin and Ancient Greek at state schools in the UK,' says founder Mai Musié of Oxford University’s Faculty of Classics.

'This animation is just the latest way in which we hope to engage teachers and students in these fascinating subjects.'

It probably isn't surprising to read that pharmaceutical drugs don't always do what they're supposed to. Adverse side effects are a well-known phenomenon and something many of us will have experienced when taking medicines.

Sometimes, these side effects can be caused when a drug hits the wrong target, binding to the wrong protein. However, the difficulty of tracking this process means that little research has been carried out.

Now, a new study led by scientists at the University of Oxford and published in Nature Chemistry has shown how a series of anti-HIV protein inhibitor drugs can interfere with the processing of a protein known as prelamin A, essential for maintaining the shape of human cells and directly related to ageing.

The researchers used mass spectrometry – a long-established way of identifying molecules by measuring their mass – to observe directly the drugs' 'hitchhiking' on the wrong protein.

Professor Dame Carol Robinson of Oxford's Department of Chemistry, corresponding author on the paper, said: 'The "hitchhiking" of drugs on incorrect targets is a common problem but isn't much studied, as it can be difficult to observe directly. You have to know which proteins to look for, and only then can you target these proteins for further research.

'The results of this study surprised us, as the drugs target HIV proteases and were not thought to bind the human metalloprotease that is involved in processing prelamin A.'

The researchers found that the anti-HIV drugs lopinavir, ritonavir and amprenavir each blocked the processing of prelamin A.

Professor Robinson added: 'The association between some anti-HIV drugs and premature ageing has been suspected for some time through observation of patients undergoing treatment, but it hasn't been proved at the molecular level. There have also been other highly publicised drugs with off-target protein side effects, including an anti-diabetes drug that caused heart attacks in some patients.

'Now that we have developed this mass spectrometry-based approach, we anticipate that it will have widespread application, since it is likely that many drugs that are designed with a specific target in mind end up hitchhiking on other protein targets. It could even be used during the drug development process to determine if drugs are binding to the wrong targets at the molecular level.'

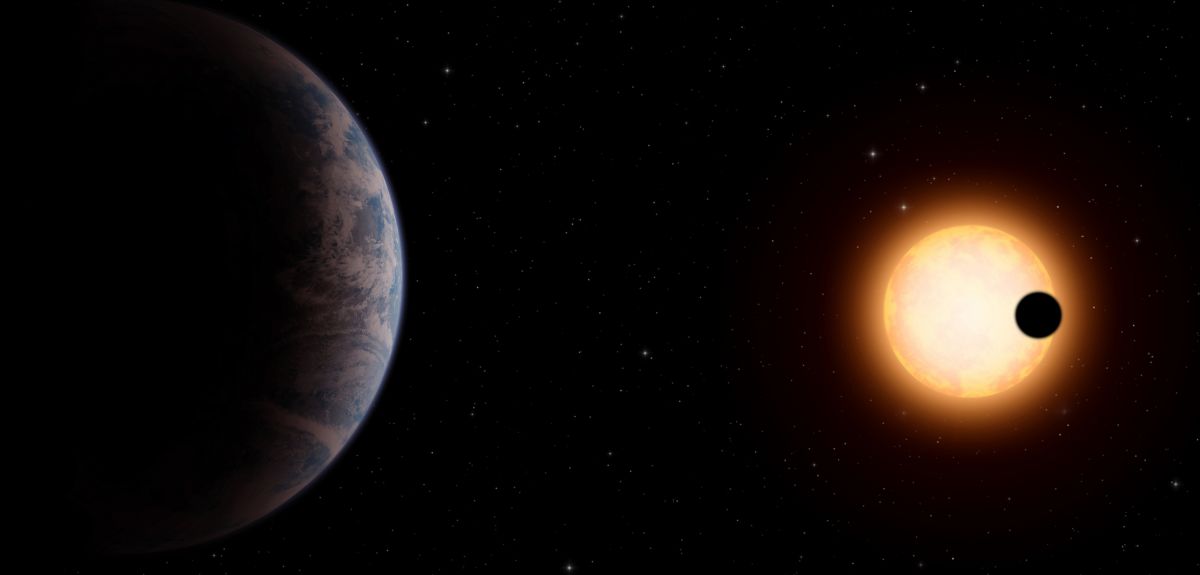

We know that the universe is roughly 14 billion years old, and that someday it is likely to end – perhaps because of a Big Freeze, Big Rip or Big Crunch.

But what can we learn by considering our own place in the history of the universe? Why does life on Earth exist now, rather than at some point in the distant past or future?

A team of researchers including astrophysicists from the University of Oxford has set about trying to answer these questions – and their results raise the possibility that we Earthlings might be the first to arrive at the cosmic party.

The paper, led by Professor Avi Loeb of Harvard University and published in the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, suggests that life in the universe is much more likely in the future than it is now. That's partly because the necessary elements for life, such as carbon and oxygen, took tens of millions of years to develop following the Big Bang, and partly because the lower-mass stars best suited to hosting life can glow for trillions of years, giving ample time for life to evolve in the future.

Dr Rafael Alves Batista of Oxford's Department of Physics, one of the study's authors, says: 'The main result of our research is that life seems to be more likely in the future than it is now. That doesn't necessarily mean we are currently alone, and it is important to note that our numbers are relative: one civilisation now and 1,000 in the future is equivalent to 1,000 now and 1,000,000 in the future.

'Given this knowledge, the question is therefore why we find ourselves living now rather than in the future. Our results depend on the lifetime of stars, which in turn depend on their mass – the larger the star, the shorter its lifespan.'

In order to arrive at the probability of finding a habitable planet, the team came up with a master equation involving the number of habitable planets around stars, the number of stars in the universe at a given time (including their lifespan and birth rate, and the typical mass of newly born stars.

Dr Batista adds: 'We folded in some extra information, such as the time it takes for life to evolve on a planet, and for that we can only use what we know about life on Earth. That limits the mass of stars that can host life, as high-mass stars don’t live long enough for that.

'So unless there are hazards associated with low-mass red dwarf stars that prevent life springing up around them – such as high levels of radiation – then a typical civilisation would likely find itself living at some point in the future. We may be too early.'

Co-author Dr David Sloan, also of Oxford's Department of Physics, adds: 'This is, to our knowledge, the first study that takes into account the long-term future of our universe – often, examinations of questions like this focus on why we arrived so late.

'Our next steps are towards refining our understanding of this topic. Now that we have knowledge of a wide catalogue of exoplanets, the issue of whether or not we are alone becomes ever more pressing.'

- ‹ previous

- 119 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?