Features

Do you speak Latin? You probably do. If you’ve ever used a memo, or got a train via London, or watched Arsenal versus Watford, you’re a bona fide speaker.

Latin is everywhere, even though most of us don’t learn it at school. But researchers in the Classics in Communities project, based in the Classics Faculty, have been exploring how learning Latin at a young age can impact children’s cognitive development.

“There are so many benefits of learning Latin,” Dr Arlene Holmes-Henderson, a researcher in the project, says. “As well as being an interesting curriculum subject in its own right, it can also support the development of literacy skills and critical skills.”

As part of her research, she has been tracking groups of primary school students in Scotland, the West Midlands, Oxfordshire and London. She has gathered data about students’ reading and writing proficiency before and after they learn Latin.

And she says that learning Latin helps children in other areas of life. “Our data definitely supports the hypothesis that learning Latin in primary school is a good educational choice,” she says.

The researchers have looked closely at socially and economically disadvantaged areas. There, they’ve found that learning Latin can have even more of a positive impact. “In these schools, learning Latin can make a significant difference to learners’ progress,” Dr Holmes-Henderson says.

And it’s not just academic—learning Latin can also help children develop cultural literacy, which enriches their understanding of the contemporary world by making them familiar with classical references. Has anyone ever told you to carpe diem? There’s that Latin again, encouraging you to seize the day.

There may be plenty to gain from learning Latin, but many children simply don’t get the opportunity to have a go at it. This is another area where Classics in Communities provides help.

“Since 2014, when Latin and Greek were named in the English National Curriculum as languages suitable for study in primary schools, we have been running training courses and providing support for primary school teachers around the UK,” Dr Holmes-Henderson explains.

Through the project website, Classics in Communities has been providing resources for teachers who have little experience of Latin themselves. This way, they hope that more and more primary school children will have the opportunity to learn.

And Latin can also be a lot of fun. “The legacy of the Romans encompasses literature, art, architecture, philosophy, history and language," says Dr Holmes-Henderson.

"Learning Latin helps young people begin to discover what life was like for the Romans. Graffiti from the walls of Pompeii are short and relatively simple, so even at primary school level, children can engage with some real Latin.”

If you like the sound of that, carpe diem, and try some Latin for yourself. Remember, audaces fortuna iuvat – fortune favours the brave.

Dr Holmes-Henderson’s book, Forward with Classics: Classical languages in schools and communities, will be published by Bloomsbury Academic this year (co-edited with Steven Hunt and Mai Musie).

Professor Tamsin Mather, a volcanologist in Oxford's Department of Earth Sciences reflects on her many fieldwork experiences at Massaya volcano in Nicaragua, and what she has learned about how they effect the lives of the people who live around them.

Over the years, fieldwork at Masaya volcano in Nicaragua, has revealed many secrets about how volcanic plumes work and impact the environment, both in the here and now and deep into the geological past of our planet.

Working in this environment has also generated many memories and stories for me personally. From watching colleagues descend into the crater, to meeting bandits at dawn, or driving soldiers and their rifles across the country, or losing a remotely controlled miniature airship in Nicaraguan airspace and becoming acquainted with Ron and Victoria (the local beverages), to name but a few.

I first went to Masaya volcano in Nicaragua in 2001. In fact, it was the first volcano that I worked on for my PhD. It is not a spectacular volcano. It does not have the iconic conical shape or indeed size of some of its neighbours in Nicaragua. Mighty Momotombo, just 35 km away, seems to define (well, to me) the capital Managua’s skyline. By comparison, Masaya is a relative footnote on the landscape, reaching just over 600 m in elevation. Nonetheless it is to Masaya that myself and other volcanologists flock to work, as it offers a rare natural laboratory to study volcanic processes. Everyday of the year Masaya pumps great quantities of volcanic gases (a noxious cocktail including acidic gases like sulphur dioxide and hydrogen chloride) from its magma interior into the Nicaraguan atmosphere. Furthermore, with the right permissions and safety equipment, you can drive a car directly into this gas plume easily bringing heavy equipment to make measurements. I have heard it described by colleagues as a ‘drive-through’ volcano and while this is not a term I like, as someone who once lugged heavy equipment up 5500 m high Lascar in Chile, I can certainly vouch for its appeal.

Returning for my fifth visit in December 2017 (six years since my last) was like meeting up with an old friend again. There were many familiar sights and sounds: the view of Mombacho volcano from Masaya’s crater rim, the sound of the parakeets returning to the crater at dusk, the pungent smell of the plume that clings to your clothes for days, my favourite view of Momotombo from the main Managua-Masaya road, Mi Viejo Ranchito restaurant – I could go on.

But, as with old friends, there were many changes too. Although in the past I could often hear the magma roaring as it moved under the surface, down the vents, since late 2015 a combination of rock falls and rising lava levels have created a small lava lake visibly churning inside the volcanic crater. This is spectacular in the daytime, but at night the menacing crater glow is mesmerising and the national park is now open to a stream of tourists visiting after dark. Previously, I would scour the ground around the crater for a few glassy fibres and beads of the fresh lava, forced out as bubbles burst from the lava lake (known as Pele’s hairs and tears after the Hawaiian goddess of the volcano – not the footballer) to bring back to analyse. Now the crater edge downwind of the active vent is carpeted with them, and you leave footprints as if it were snow. New instruments and a viewing platform with a webcam have been put in, in place of the crumbling concrete posts where I used to duct-tape up my equipment.

This time my mission at Masaya was also rather different. Before I had been accompanied solely by scientists but this time I was part of an interdisciplinary team including medics, anthropologists, historians, hazard experts and visual artists. All aligned in the shared aim of studying the impacts of the volcanic gases on the lives and livelihoods of the downwind communities and working with the local agencies to communicate these hazards. Masaya’s high and persistent gas flux, low altitude and ridges of higher ground, downwind of it, mean that these impacts are felt particularly acutely at this volcano. For example, at El Panama, just 3 km from the volcano, which is often noticeably fumigated by the plume, they cannot use nails to fix the roofs of their houses, as they rust too quickly in the volcanic gases.

The team was drawn from Nicaragua, the UK and also Iceland, sharing knowledge between volcano-affected nations. Other members of the team had been there over the previous 12 months, installing air quality monitoring networks, sampling rain and drinking water, interviewing the local people, making a short film telling the people’s stories and scouring the archives for records of the effects of previous volcanic degassing crises at Masaya. Although my expertise was deployed for several days installing new monitoring equipment (the El Crucero Canal 6 transmitter station became our rather unlikely office for part of the week), the main mission of this week was to discuss our results and future plans with the local officials and the communities affected by the plume.

Having worked at Masaya numerous times, mainly for more esoteric scientific reasons, spending time presenting the very human implications of our findings to the local agencies, charged with monitoring the Nicaraguan environment and hazards, as well managing disasters was a privilege. With their help we ran an information evening in El Panama. This involved squeezing 150 people into the tiny school class room in flickering electric light, rigging up the largest TV I have ever seen from the back of a pick-up and transporting 150 chicken dinners from the nearest fried chicken place! But it also meant watching the community see the film about their lives for the first time, meeting the local ‘stars’ of this film and presenting our work where we took their accounts of how the plume behaves and affects their lives and used our measurements to bring them the science behind their own knowledge.

Watching the film it was also striking to us that for so many of this community it was the first time they had seen the lava lake whose effects they feel daily. Outside the school house there were Pele’s hair on the ground in the playground and whiffs of volcanic gas as the sun set – the volcano was certainly present. However, particularly watching the film back now sitting at home in the UK, I feel that with this trip, unlike my others before, it is the people of El Panama that get the last word rather than the volcano.

Professor Chris Butler of the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, and GP in the Cwm Taf University Health Board in Wales, is the lead investigator in the world’s largest clinical trial in the community of the controversial flu drug oseltamivir (Tamiflu). He explains the background to the trial and what the team are looking to achieve.

There is widespread uncertainty over whether people with flu symptoms should routinely be treated with antiviral drugs like oseltamivir – also known as Tamiflu - in the community, with a debate raging in the media about the drug’s use each winter. To help us get some answers about whether to treat, and if so, who might benefit most, we’ve so far recruited 2,000 people into a clinical trial to test the clinical and cost effectiveness of oseltamivir in primary care and provide some much-needed real world evidence about this treatment.

Led in the UK by our team in Oxford University’s Primary Care Clinical Trials Unit, and coming together with colleagues across Europe, the ALIC4E trial investigates whether oseltamivir is cost effective and beneficial to patients consulting their general practitioner with flu symptoms. In particular, it will understand if older people, infants, people with other health conditions, those treated early, or those with particularly severe flu can benefit from the treatment.

ALIC4E is the first publically funded randomised controlled trial of its kind to assess antiviral treatment for influenza in primary care and is a collaboration between researchers in the UK, The Netherlands and Belgium. Overall we aim to recruit at least 2,500 participants across 16 countries and, like most of our clinical studies in primary care, we do this by working closely with GP practices.

Since launching in 2015, 324 participants have been recruited across England and Wales - 138 in Oxford, 86 in Southampton and 100 in Cardiff, with the trial as a whole reaching the milestone of 2,000 participants this week.

The trial is an initiative of the Platform for European Preparedness Against (Re-) emerging Epidemics (PREPARE) consortium. Funded by the European Commission’s FP7 Programme, PREPARE was set up to support research organisations to respond rapidly to pandemics with clinical studies that can provide real-time evidence to inform the public health response.

The antiviral oseltamivir is a member of a class of drugs called neuraminidase inhibitors. These drugs are stockpiled and recommended by public health agencies worldwide for treating and preventing severe outbreaks of seasonal and pandemic influenza, yet some experts suggest the evidence supporting their use is lacking. The drug was widely used during the ‘swine ‘flu’ pandemic, for example, but no trial was done of its clinical and cost effectiveness.

Having reached the milestone of recruiting 2,000 patients into the critically important ALIC4E study is an incredible international achievement that is worth celebrating. Especially when there seems to be a particularly widespread flu outbreak, it’s a real shame that we don’t confidently know which people with symptoms of the flu should be prescribed antiviral drugs, and the cost-effectiveness of this treatment in terms of helping people return to their usual activities.

The resource implications for the health service and implications for patient well-being are considerable, especially given the debate around the effectiveness of antiviral treatment for influenza. By providing evidence through a study of this scale, the results will be of great interest to governments, policy makers, companies, practitioners, and members of the public.

We urgently need studies like ALIC4E embedded in everyday general practice to guide care for common and potential serious conditions, and address the questions that matter most to patients. We are working towards making it possible for people to participate in clinical trials within two weeks of a pandemic emerging, so evidence from these trials can then inform care during the pandemic itself, rather than those much needed answers coming along once the pandemic is over.

Have you ever found yourself pages-deep in a Google search, desperate for a quick fix for your medical woes?

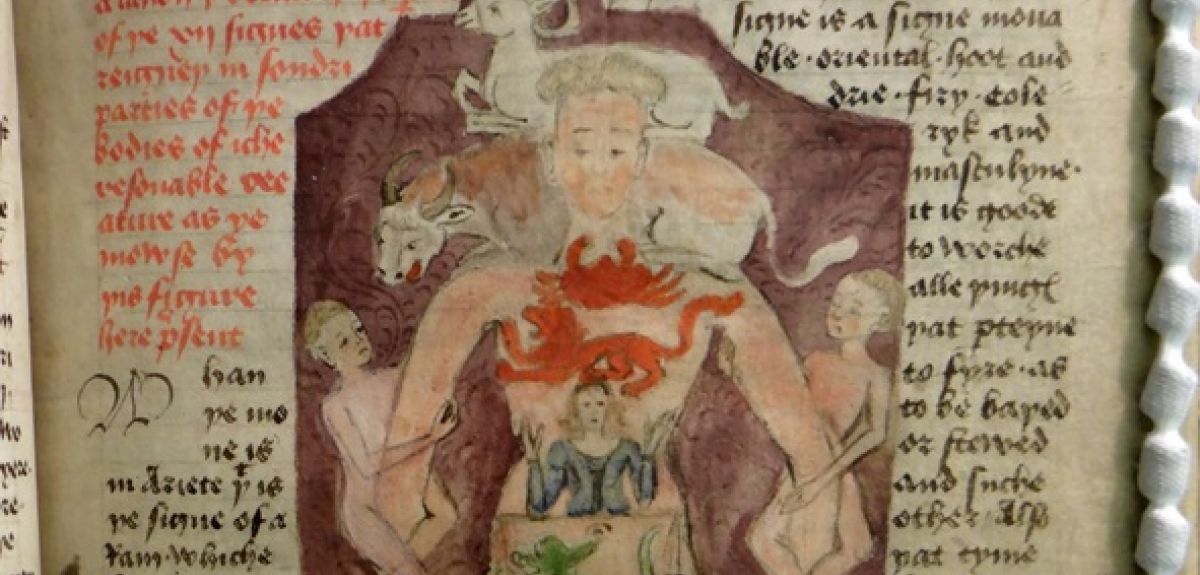

Google may be a more recent invention, but tips, tricks, and tonics for even the quirkiest of ailments have been around for hundreds of years. And Professor Daniel Wakelin, the Jeremy Griffiths Professor of Medieval English Palaeography, has been digging up the most disgusting treatments for a new book on medieval remedies.

Professor Wakelin and a group of master’s students have been studying the Bodleian’s collection of medieval manuscripts to collect the word-of-mouth, definitely-not-scientifically-proven medical advice that was passed around 500 years ago. A collection of the forty-eight most eye-watering remedies have been published in a new book, 'Revolting Remedies from the Middle Ages'.

The glimpse the book gives into medieval medicine isn’t pretty. The remedy for gout recommends plucking, cutting open, baking, and pulverizing an owl, before gently rubbing it over your wound.

Professor Wakelin is keen to emphasise that the collection is the furthest thing from medical advice. “We chose the ones that were the most scandalous and the most disgusting,” he says. “So definitely don’t try them at home.”

A sensible piece of advice—unless you particularly fancy heating eight-day old urine over a fire and washing your face with it (apparently, medieval spot-sufferers hadn’t yet discovered Clearasil).

The remedies give us a fascinating insight into medieval life. Originating in the fifteenth century, the remedies were scribbled in margins and flyleaves. Originally, many of the remedies were probably passed on by word-of-mouth. But in the 1400s, when the number of people who could read and write was increasing, the remedies were finally jotted down.

This often means that, along with the medical advice, there are a few more ambitious suggestions. Professor Wakelin’s favourite is a remedy to make somebody fall in love with you.

“Totally unethical,” he says. “But intriguing.”

It also calls for a strong stomach. According to the remedy, all you need to do is mix your own sweat with the shavings from the back of your feet and some of your own sun-dried dung. Take a swig of that concoction, and whoever catches your eye will be yours. I hope they’re worth it.

Although the book only features the freakiest, most of the remedies that the researchers found weren’t so outlandish. Interestingly, some of the remedies might even be found in health stores today, such as fennel for a stomach upset.

This shows us, then, that there’s more to the medieval world that meets the eye.

“I think the remedies show us a lot about the medieval worldview,” Professor Wakelin says. For example, there are many remedies for blindness. “Sight takes so much expertise to fix, people must have been despairing when their eyes went wrong.”

But the solutions to such sight ailments sound eccentric to the twenty-first century reader. One suggests mixing sheep dung with vinegar and smearing it in your eyes. We definitely don’t recommend trying that one, but this perfect mixture of comedy, revulsion, and curiosity is what Professor Wakelin hopes people will enjoy.

If your appetite has been whetted (or if you’ve lost it completely), you can buy the book, which has been published by the Bodleian Library.

There will also be a Bodleian exhibition on medieval book design to accompany it, Designing English, featuring an array of weird and wonderful medical images.

The sudden death of over 200,000 saiga antelopes in Kazakhstan in May 2015, which affected more than 80% of the local population and more than 60% of the global population of this species, baffled the world. In just three weeks, entire herds of tens of thousands of healthy animals, died of haemorrhagic septicaemia across a landscape equivalent to the area of the British Isles in the Betpak-Dala region of Kazakhstan. These deaths were caused by Pasteurella multocida bacteria.

But this pathogen most probably was living harmlessly in the saigas’ tonsils up to this point, so what caused this sudden dramatic Mass Mortality Event (MME)?

New research by an interdisciplinary, international research team has shown that many separate (and independently harmless) factors contributed to this extraordinary phenomenon. In particular, climatic factors such as increased humidity and raised air temperatures in the days before the deaths apparently triggered opportunistic bacterial invasion of the blood stream, causing septicaemia (blood poisoning).

By studying previous die-offs in saiga antelope populations, the researchers were able to uncover patterns and show that the probability of sudden die-offs increases when the weather is humid and warm, as was the case in 2015.

The research also shows that these very large mass mortalities, which have been observed in saiga antelopes before (including in 2015 and twice during the 1980s), are unprecedented in other large mammal species and tend to occur during calving. This species invests a lot in reproduction, so that it can persist in such an extreme continental environment where temperatures plummet to below -40 celsius in winter or rise to above 40 celsius in summer, with food scarce and wolves prowling. In fact, it bears the largest calves of any ungulate species; this allows the calves to develop quickly and follow their mothers on their migrations, but also means that females are physiologically stressed during calving.

With this strategy, high levels of mortality are to be expected, but the species’ recent history suggests that die-offs are occurring more frequently, potentially making the species more vulnerable to extinction. This includes, most recently, losses of 60% of the unique, endemic Mongolian saiga sub-species in 2017 from a virus infection spilling over from livestock. High levels of poaching since the 1990s have also been a major factor in depleting the species, while increasing levels of infrastructure development (from railways, roads and fences) threaten to fragment their habitat and interfere with their migrations. With all these threats, it is possible that another mass die-off from disease could reduce numbers to a level where recovery is no longer possible. This needs to be countered by an integrated approach to tackling the threats facing the species, which is ongoing under the Convention on Migratory Species’ action plan for the species.

This research was conducted as part of a wide international collaboration, adopting a ‘One Health’ approach – looking at the wildlife, livestock, environmental and human impacts that have driven disease emergence in saiga populations.

Adopting such a holistic approach has enabled the research team to understand the wider significance of die-offs in saiga populations, beyond simply the proximate causes of the 2015 epidemic.

Professor Richard Kock, Professor in Emerging Diseases lead researcher at the Royal Veterinary College, said: 'The recent die-offs among saiga populations are unprecedented in large terrestrial mammals. The 2015 Mass Mortality Event provided the first opportunity for in-depth study, and a multidisciplinary approach has enabled great advances to be made. The use of data from vets, biologists, botanists, ecologists and laboratory scientists is helping improve our understanding of the risk factors leading to MMEs – which was beneficial when another MME occurred, this time in Mongolia in 2017. Improved knowledge of disease in saigas, in the context of climate change, livestock interactions and landscape changes, is vital to planning conservation measures for the species’ long-term survival.'

Professor EJ Milner-Gulland, Tasso Leventis Professor of Biodiversity at Oxford University, said: 'This important research was possible due to a strong partnership between European universities, governmental and non-governmental Institutions in Kazakhstan, and international bodies such as the Food and Agriculture Organisation and Convention on Migratory Species, as well as generous funding from the UK government and conservation charities worldwide. During the more recent saiga disease outbreak in Mongolia, this international partnership was useful for supporting in-country colleagues, for example by providing emergency response protocols. It’s excellent to see the real-world value of research partnerships of this kind, and the great advances we have made in understanding disease in saigas thanks to such a productive collaboration.'

Mr Steffen Zuther, Project manager for Kazakhstan at the Frankfurt Zoological Society/Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan, said: 'This research is not only the first of its kind through its complexity and interdisciplinary approach, it also helps in capacity building inside Kazakhstan and shaping the public opinion towards a more evidence based thinking. MMEs are a major threat for the saiga antelope and can wipe out many years of conservation work and saiga population growth in just a few days. Therefore, understanding these MMEs, what triggers them and what can be done to combat them is extremely important to develop effective saiga conservation strategies. The triggering of such MMEs in saiga through weather conditions shows that not much can be done to prevent them occurring, and therefore how important it is to maintain saiga populations of sufficient size for the species to survive such catastrophes.'

Professor Mukhit Orynbayev, Senior Researcher at the Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems, Kazakhstan, said: 'Kazakhstan plays a crucial role for the conservation of saiga, and its government takes this very seriously. This research is an important component of the government's strategy for the conservation of the species, and we as researchers are grateful for the support we have received during our work. Through several years of work on this subject, the team of the RIBPS has gained experience in fieldwork and laboratory tests. This allows us to react quickly to any disease outbreak and get a diagnosis for it.'

- ‹ previous

- 82 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria