Features

Particular smells can be incredibly evocative and bring back very clear, vivid memories.

Maybe you find the smell of freshly baked apple pie is forever associated with warm memories of grandma's kitchen. Perhaps cut grass means long school holidays and endless football kickabouts. Or maybe catching the scent of certain medicines sees you revisit a bout of childhood illness.

What's remarkable about the power of these 'associative memories' – connecting sensory information and past experiences – is just how precise they are. How do we and other animals attach distinct memories to the millions of possible smells we encounter?

There's a clear advantage in doing so: accurately discriminating smells indicating dangers while making no mistakes in following those that are advantageous. But it's a huge information processing challenge.

Researchers at Oxford University's Centre for Neural Circuits and Behaviour have discovered that a key to forming distinct associative memories lies in how information from the senses is encoded in the brain.

Their study in fruit flies for the first time gives experimental confirmation of a theory put forward in the 1960s which suggested sensory information is encoded 'sparsely' in the brain.

The idea is that we have a huge population of nerve cells in many of our higher brain centres. But only a very few neurons fire in response to any particular sensation – be it smell, sound or vision. This would allow the brain to discriminate accurately between even very similar smells and sensations.

'This "sparse" coding means that neurons that respond to one odour don't overlap much with neurons that respond to other odours, which makes it easier for the brain to tell odours apart even if they are very similar,' explains Dr Andrew Lin, the lead author of the study published in Nature Neuroscience.

While previous studies have indicated that sensory information is encoded sparsely in the brain, there's been no evidence that this arrangement is beneficial to storing distinct memories and acting on them.

'Sparse coding has been observed in the brains of other organisms, and there are compelling theoretical arguments for its importance,' says Professor Gero Miesenböck, in whose laboratory the research was performed. 'But until now it hasn’t been possible experimentally to link sparse coding with behaviour.'

In their new work, the researchers demonstrated that if they interfered with the sparse coding in fruit flies – if they 'de-sparsened' odour representations in the neurons that store associative memories – the flies lost the ability to form distinct memories for similar smells.

The flies are normally able to discriminate between two very similar odours, learning to avoid one and head for the other. This is controlled by the neurons that store associative memories, called Kenyon cells. There's a separate nerve cell that acts as a control system to dampen down the activity the Kenyon cells, preventing too many of them from firing for any particular odour.

Dr Lin and colleagues showed that if this single nerve cell is blocked, the odour coding in Kenyon cells becomes less sparse and less able to discriminate between smells. The flies end up attaching the same memory to similar, yet different, odours.

Sparse coding does turn out to be important for sensory memories and our ability to act on them. Although the research was carried out in fruit flies, the scientists say sparse coding is likely to play a similar role in human memory.

Although sparse coding in the brain would seem to require much greater numbers of nerve cells, that cost appears to be worth it in being able to form distinct associative memories and act on them – thankfully. A life of experiences and memories is so much more full as a result.

Chemistry probably isn't the first thing that comes to mind when you see skeletons at a museum, but an understanding of chemical reactions is essential to the work of the modern museum conservator.

Bethany Palumbo, Conservator for Life Collections in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, used her chemical expertise to restore centuries-old whale bones for the Museum's recent reopening. The fruits of her team's hard work are now on display for all to see at the Museum, which reopened on 15 February to a staggering 30,000 visitors in the first week alone.

'Chemistry is a key element of conservation,' says Bethany. 'When I began the whale project in mid-2013, there had been no documented preparation of the skeletons for over a century – some of them have been at the Museum since 1860! We had to examine every inch of each whale and research the chemical composition of their bones and the oils they secrete before deciding how to proceed.'

Cleaning and preserving old bones is an intricate, technical task and each treatment must be tailored to the individual bone. Whale bones are especially challenging, as fatty oils slowly seep out over the years.

'When we began the project, there were thick layers of oxidised natural oils on many of the bones,' says Beth. 'This unsightly residue not only attracts dust and makes specimens look dirty, but it is also acidic in nature so can damage the bone. When we tested the oils, they had an acidity of pH4 – about the same as most acid rain. The density of the oil varied across the specimens, and the skulls tended to have more oil than other areas. Whales have a hollow area in front of their skulls filled with oil to focus sonar signals which seeps into the bones where it can remain for centuries after they die. Areas of bone, still saturated with this acidic oil, were in some cases crumbling with a gritty texture similar to wet sand.'

To remove the oily secretions, Bethany and her team brushed solutions of ammonia and purified water onto the bones. Ammonia is an alkaline chemical that works by a process known as saponification that converts fats into soap. Ammonia breaks fat molecules up into their glycerol and fatty acid elements to produce soluble salts and soap scum, which can simply be wiped or vacuumed from the surface. Concentrations of ammonia varied depending on the areas being treated.

'Particularly oily areas, such as the humpback skull needed to be treated with 10% ammonia, whereas we used only 5% for the other specimens,' explains Beth. 'We were careful when the solution came into contact with the cartilage, as this can also disintegrate with the alkaline ammonia solution. There's always a balance to strike with conservation, the treatment method you choose on should never cause more harm than good.'

As well as damaging the bones, the acidic oil also caused verdigris – the green pigment currently coating the Statue of Liberty – to blossom from the copper wires inside the bones used to support the skeletons. Verdigris can be build up over time when copper reacts with oxygen, and is rapidly accelerated by acids.

'The verdigris on the copper wires was exploding from the drilled holes in the bone, causing the wires to weaken and snap when we tried to remove them,' says Beth. 'We ended up using a soldering iron to heat the wire, softening the surrounding cartilage just enough for us to pull the wires out and then vacuum out any residues.

'We have now replaced the wires with stainless steel, which is strong and resistant to the environmental conditions of the museum. We considered alternative methods of putting the skeletons back together, but it made more sense to use the existing holes in the bones to avoid creating further damage to the skeletons.'

Almost paradoxically, the conditions of the Museum environment are actually rather bad for the bones. Ultraviolet sunlight from the glass ceiling destroys collagen in the bones, weakening their structure, and the fluctuating temperatures cause the bones to expand and shrink, weakening joints. Before the roof was repaired, the fluctuating humidity worsened this problem.

'Technically, the best place for these bones would be a cool, dark room,' explains Beth. 'There is often a trade-off between conservation and education, so we have to do the best we can to make sure the skeletons can cope when out in the open for all to see. The adhesives we select, for example, have to be able to withstand high heats and fluctuating temperatures.'

Finally, when reconstructing the skeletons during the restoration process, the team tried to correct the anatomical features of the whales where possible.

'Dried cartilage will shrink over time, pulling the bones into unnatural positions,' says Beth. 'We corrected this by repositioning bones with new wires where possible, but some areas were just too fragile. Also, since we only had six months to complete the project, we simply didn't have the time to correct everything. There are some parts of the fins and ribcages that remain slightly incorrect, which is frustrating, but the skeletons are still far more anatomically correct than when we started.

'After a thorough restoration project, I think our whales will have a few good decades more on display. I'm extremely proud of what my team achieved in a short space of time, and hope that visitors will continue to enjoy seeing the whales in the Museum for years to come.'

The conservation treatment of the whale bones was documented in real time at the Once in a Whale blog, where you can learn more about the whole process.

Love is in the air for many of us today – but it's always a time for romance at the Ashmolean Museum, which has been featuring a number of Valentine's Day-themed works of art from its collections on its Twitter feed throughout the day.

Two merchants compete for the love of the geisha Kasaya Sankatsu

Two merchants compete for the love of the geisha Kasaya SankatsuUtagawa Kunisada (1786–1864)

Woodblock triptych print, c. 1849

Here, two merchants compete for the love of the geisha Sankatsu. Sankatsu holds the two halves of a red sake cup in her hands, demonstrating her divided loyalties towards the two men.

The Love Letter

The Love LetterThomas Sully (1783–1872)

Oil on canvas, 1834

One of Sully's most popular compositions, of which he painted numerous replicas. This version was presumably bought by the tenor Joseph Wood and his wife, the soprano Mary Ann Paton, during their American tour in 1836 when Sully painted Mary Ann's portrait, or perhaps when Sully visited England to paint Queen Victoria in 1837.

Acme and Septimius

Acme and SeptimiusFrederic Lord Leighton (1830–1896)

Oil on canvas, 1868

The subject of this scene of idyllic love is taken from Catullus, Carmine XV. Both the round shape and composition are indebted to Raphael's Madonnas. The background includes the rose, traditionally the symbol of love, and orange trees. When it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1868, it was praised by critics, who noted with approval Leighton's chaste treatment of the scene.

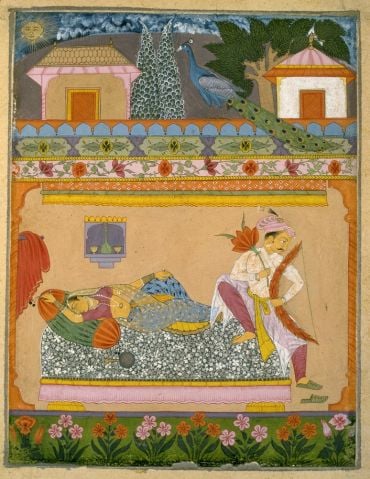

Lovers at dawn, illustrating the musical mode Raga Vibhasa

Lovers at dawn, illustrating the musical mode Raga VibhasaNorth Deccan, India

Gouache on paper, c.1675

The musical mode Vibhasa ('radiance') is normally performed at dawn. It is conceived pictorially as a noble couple who have passed the night together. Often, as the lady sleeps, her lover may aim his bow to shoot the crowing cock. But here he holds a flower bow and arrow like the love god Kama, and the peacock is unthreatened. Ragamala painting became a highly popular genre in the Mughal period.

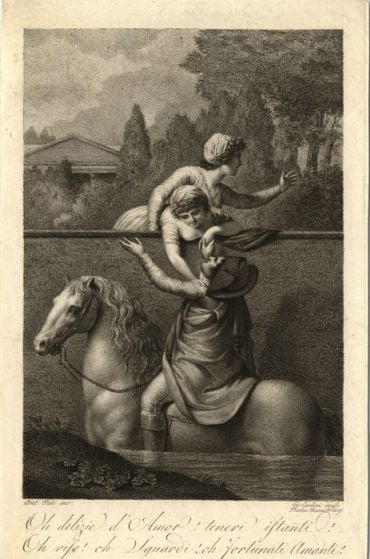

Oh delizie d'Amor!

Oh delizie d'Amor!Giovanni Cardini after Antonio Fedi

Etching and stipple, c.1810-20

An element of drama, and plenty of exclamation marks, are all provided by this Italian scene of elopement.

Love bringing Alcestis back from the Grave

Love bringing Alcestis back from the Grave

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones

Watercolour and chalk on paper, 1863

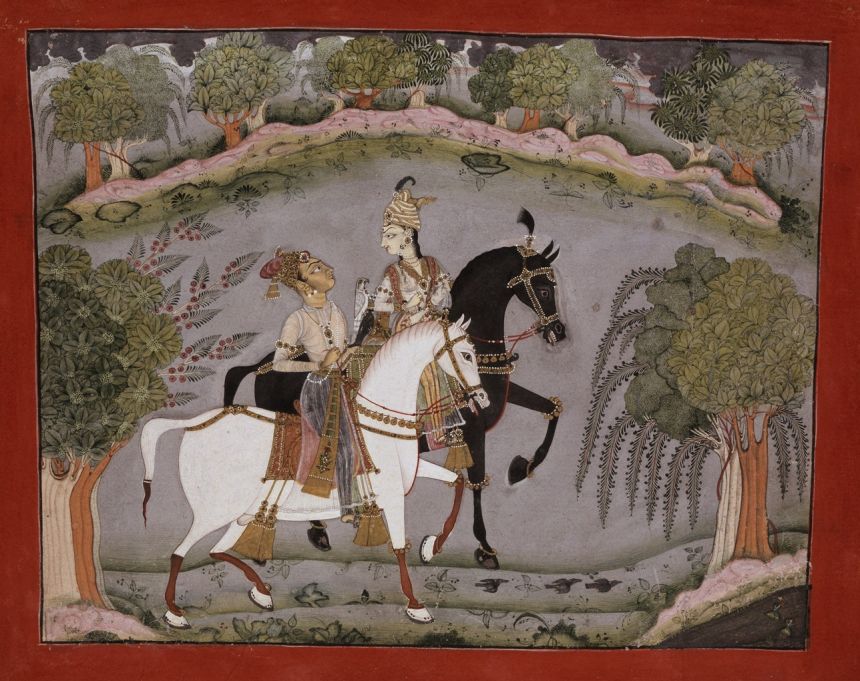

Baz Bahadur and Rupmati

Baz Bahadur and Rupmati

Kulu, northern India

Gouache with gold and silver on paper, c.1720

A cultivated prince and gifted singer, the Muslim Sultan Baz Bahadur, Sultan of Malwa, was devoted to the company of musicians and dancing girls. His favourite was Rupmati, a celebrated beauty who became his constant companion. The love of Baz Bahadur and his Hindu mistress became a popular theme of poetry and song in late Mughal India.

All images copyright Ashmolean Museum.

In the battle against the mosquitoes that carry deadly human diseases scientists are recruiting a new ally: a genetic enemy within the mosquito's DNA.

These new recruits are homing endonuclease genes (HEGs), 'selfish' genetic elements that have a better than normal chance of being passed on between generations despite being potentially harmful to an individual.

HEGs can recognise and 'cut' a short sequence of DNA on one of a pair of chromosomes, then fool an organism's repair mechanism into copying the HEG across onto the other chromosome. The HEG gets inserted within the 'cut' sequence of 'normal' DNA whilst the 'cut' is repaired. It is this 'drive' that makes HEGs particularly interesting for disrupting DNA and hence mosquito control.

Crucially HEGs can be used to recognise and disrupt a bit of DNA that really matters – that is important for an individual mosquito to survive from egg to adult.

'HEGs occur naturally in some simple organisms, such as single-celled fungi, and have been artificially inserted into the genomes of other organisms, notably the mosquito species, Anopheles gambiae, that is the main vector of human malaria,' explains Mike Bonsall of Oxford University's Department of Zoology.

'They can be used either to suppress mosquito populations by altering the inheritance patterns of genes (for example genes that affect survival) or to alter the genetic structure of mosquito populations by driving genes that alter the key mosquito characteristics (such as the ability to transmit a pathogen).'

Such a genetic approach could be an important weapon against diseases like malaria, which is responsible for up to 1.6 million deaths a year worldwide, by reducing the numbers of disease-carrying adult female mosquitoes in a local area to such a level that there aren’t enough to support and pass on the infection to humans.

But HEGs are not simply 'genetic homing missiles' that kill mosquitoes: such selfish genetic elements have to spread, the individuals carrying them have to compete, and populations respond and change.

'While it is necessary to understand the population genetics and patterns of HEG inheritance, the effectiveness of HEGs requires an understanding of both the ecology and genetics. The population dynamics and ecology determine how individuals in a population compete, grow and disperse,' Nina Alphey of Oxford University's Department of Zoology tells me.

'Population genetics might predict that a HEG that reduces survival will naturally spread through a population, but that does not necessarily mean the population will be reduced enough to significantly alter disease transmission. Simply knowing the genetics is not quite enough.'

To explore how interactions between ecology and genetics can influence the effectiveness of HEG-based mosquito control Mike and Nina developed a mathematical model as part of a BBSRC-funded project. They report their findings this week in Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

'One significant finding from our work is that we show that the type of competition affects the outcome of HEG-based control. If competition is particularly strong, alterations in early larval survival could lead to an increase in mosquito population size, rather than its decline,' Mike explains. 'This occurs as the population is 'freed' from its natural ecological control – which in mosquitoes occurs in the late-larval stage.

'We also showed that if a HEG does not just reduce the mosquito's survival, but also changes how that mosquito fares during the larval competition, it could achieve a better reduction in mosquito numbers than an identical HEG that simply reduced survival. The effects of a HEG that affects both survival and timing of competition would need to be carefully monitored to ensure that population suppression is achieved.'

Whilst with larger animals it might be possible to monitor individuals as a way of understanding population dynamics this is impractical for populations of thousands of insects, such as mosquitoes, linked to tiny patches of habitat – a small pond or even just a container of water.

Mathematical models are the only practical way of studying the links between genetics and ecology and identifying potential pitfalls in any genetic insect control approach – such as HEGs acting early in an insect's lifecycle being less effective than ones acting later on.

'We are working on extending our modelling approaches to understanding the control of mosquitoes by integrating economics and the cost-effectiveness of control programmes. This involves linking the costs of rearing modified mosquitoes, the epidemiology of the disease, the movement of people and mosquitoes and evaluating the public health benefits,' says Nina. The team have created an online game that highlights some of the issues faced by any control programme.

There are a lot of factors to consider in a future model: another variable is that in the wild populations compete with other species. For instance the malaria-carrying Anopheles gambiae mosquito may compete with various other species, and the dengue-carrying Aedes aegypti and the less competent Aedes albopictus compete with each other in some regions, so that reducing the numbers of one disease-carrying species could boost the numbers of another.

Mike tells me: 'We hope to work out when and where it might be appropriate to combine these insect control strategies with other disease implementation methods (such as vaccination programmes). Also thinking on how these insect control strategies can be used to control the spread of resistance to conventional control programmes is a new BBSRC project we have very recently started.'

A group of Modern Languages students from Oxford University are documenting their time abroad in Brazil via the BBC.

'Para Inglês Ver', or 'For the English to See', is a series of blogs hosted by BBC Brasil that allows the students to share their impressions of the country – from music, arts and culture to race relations and politics – as they travel around during the first few months of 2014.

The blogs are written by Oxford Modern Languages students reading Portuguese combined with another language or other subjects.

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily GreenShe told Arts at Oxford: 'The project evolved from a series of meetings. I met Juliana Iootty of the BBC during Brazil Week, a cultural event organised by one my tutors, Dr Claire Williams.

'Juliana suggested that some of the Portuguese students should come and visit Broadcasting House, where we were given a tour and talked about potential projects. We then had a second meeting with Silvia Salek of BBC Brasil, who suggested the blog.

'So it was pretty organic, and Juliana and Silvia were both really encouraging and just as enthusiastic about the project as we were.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily GreenShe said: 'From living with a host family and talking to them, as well as colleagues and friends, I know that the things I've written about will get a debate going among Brazilian people. They're the kinds of topics that come up on the commute to work, or in the staff room, or round the dining table.

'The writing process has been difficult, as there is so much I want to say, with so many subtleties. Writing about social issues for social media is a world away from our 2000-word essays. But it has been great to step out of the books and into the real world.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily Green'The students sometimes move to Brazil with certain preconceptions about the country, and it is always fascinating to see how their views and understanding of Brazilian culture change.

'It will be an opportunity for Brazilians to see themselves through young foreign eyes, and for the students to share what they learn during their time in the country – in terms of both language and culture.

'The BBC Brasil website is an amazing platform for the work of our future Brazilianists.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily GreenShe said: 'The title is so perfect, really. To get a sense of what it really meant, I would ask people I met what the phrase meant to them. Many people hadn't heard it before but for most it was something false, or something put on just for show.

'In my head I find it easiest to understand it as "sweeping things under the carpet" – not just because you don't want to deal with a problem, but because you don't want anyone to see there is a problem at all.

'So in the first post I was trying to get my head round the title but also highlight a few things I had spied under the metaphorical rug of sunny Brazil – the way there are always two sides to the coin in every aspect of the country. For example, luxury new-age shopping centres sit side-by-side with interior country landscapes that remind me of Nepal; breathtaking natural beauty is coupled with really shocking industrial pollution.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily Green'The Oxford University students taking part in this project are assuming the role of modern travellers who set out to explore Brazil, but instead of explaining it to their fellow countrymen they are talking to a Brazilian audience.

'We hope that this will be a two-way process in which Brazilians can learn from these students' perspectives and perhaps see how they themselves can contribute to a more diverse understanding of their own country.'

Credit: Lily Green

Credit: Lily Green- ‹ previous

- 174 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria