Features

Field researchers, Dr Giacomo Zanello, Dr Marco Haenssgen, Ms Nutcha Charoenboon and Mr Jeffrey Lienert explain the importance of continuing to improve survey research techniques when working in rural areas of developing countries.

News about big data and artificial intelligence can leave the impression that a data revolution has made conventional research methods obsolete. Yet, many questions remain unanswerable without working directly with (and understanding) the people whose lives we are interested in. In development studies research, survey research methods therefore remain a staple of data generation, and survey data generation itself remains an active field of debate. In today’s blog, four researchers showcase recent methodological advances in rural health survey research and the advantages they bring to conventional research approaches.

Reaching People at the Margins, 25% off! (Dr Marco J Haenssgen, Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Medicine)

Generating representative data from rural areas of developing countries is a real challenge because often we lack detailed and dependable information on the local population, which makes drawing a sample very difficult. However, recent technological revolutions that we are rather familiar with – the Internet, mobile phone technology, satellite navigation – can also facilitate our work in survey research. Satellite maps in particular help us to:

(1) Select villages more rigorously: We can use satellite maps to generate or verify geo-coded village registers (e.g. censuses or the US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency) to draw geographically stratified samples. Geo-stratification ensures that we do not accidentally select only “easy” villages that represent less constrained lifestyles in the rural population.

(2) Identify and select houses within the villages more inclusively: Conventional methods to draw a sample of households require either a very laborious enumeration process by going from house to house to establish a sampling frame, and/or are likely to exclude households and settlements at the fringes of a village (e.g. a “random walk”). By using satellite images to enumerate all houses in a village, not only do we save a lot of time and money, but we can also ensure that all parts of a village are represented fairly.

(3) Reach survey sites more efficiently: The logistical benefits cut as much as 25% off the conventional survey costs and time, which can save up to £5,000 for a PhD-level survey (400 respondents in 16 villages) and £40,000 for a medium-sized two-country survey (6,000 respondents in 139 villages).

We need to appreciate that satellite-aided sampling approaches are only an addition to our survey toolkit. They do not work well in urban areas, with mobile populations, or in regions that we are not familiar with. But where they work, they are a real alternative to conventional survey approaches and can make projects feasible that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive, without compromising quality.

Taking Energy Measurement From the Lab to the Field (Dr Giacomo Zanello, School of Agriculture, Policy and Development, University of Reading)

How much energy do you burn during the day (at your job, doing household chores, or at the gym) and is this “energy expenditure” in balance with the calories you take in with your food and drinks? Historically, to answer this question, participants had to spend time in a sealed chamber in a lab which measures the change in oxygen levels while performing activities. While this provides an accurate estimate of energy use, this method is quite impractical to understand real-life settings, particularly for remote areas in a developing country context. It is in these contexts where calorie deficits are most pressing, and yet we do not know much about farmers’ energy use, differences across gender and age groups, or variations of energy use across the seasons and during health or climate-borne adversities.

Recent technological advances allow the measurement of energy expenditures of free living populations to a scale and within a budget inconceivable few years ago. Using Fitbit-like accelerometers we can capture people’s movements and use this information to estimate calorie expenditure. By wearing these devices we follow people’s activities throughout the day, weeks, and seasons and use this information to estimate their energy use. This new glimpse into how people spend their energy can improve health research in multiple domains, for example:

• Having a more accurate assessments of the incidence, depth and severity of undernutrition and poverty,

• Estimating energy requirements for specific livelihood activities, or

• Studying the effect of health conditions and illnesses on livelihood activities.

These are just some possibilities, and the data collected through this innovative methodology extends beyond health-focused research. It also enables us to learn more about how labour is distributed within rural households in developing countries, or measure production in the household and the “informal economy” to produce better estimates of the size of rural economies.

Taking energy measurement from the lab to real-life settings is not without complications. We have to make careful decisions about the devices we use (e.g. easy to wear, not requiring user interaction, not attracting too much attention), build a trusting relationship with our research participants, and acknowledge that even accelerometer-generated data only offers a partial view into energy expenditure and daily activities. Yet even this partial view can afford a completely new understanding of people’s rural livelihood.

A Qualitative Research Update for Social Network Surveys (Ms Nutcha Charoenboon, Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit)

Health and treatment hardly take place in isolation – people around us influence our behaviour, give us advice, or lend us a ride to the hospital. Public health information campaigns, too, are subject to people’s relationships because they might be communicated further or even be instrumentalised for political purposes. Perhaps it is no surprise then that there are calls for more social network research on health in developing countries, but such research faces difficult questions, like how do we ask elicit the names of people in these networks, and how we can match these names in place where one person might be addressed in several different ways (e.g. “Old Father,” “Leader,” Yod Phet, and Ja Bor).

How can we overcome such difficulties? One possibility is cognitive interviewing, consisting of a set of interview techniques to test and interpret survey questions. Among others, interviewees are given survey questions and asked to “think out loud” on how they understand and answer the question, to paraphrase the question in their own words, or to explain village life and the local context. Such information gives researchers a better grasp of local social networks, living arrangements, and people’s understanding of social network questions. In our study in rural Thailand and Lao PDR, it enabled us to drop irrelevant questions, add questions to map health social networks more comprehensively, and to identify mechanisms to locate named contacts within the village more effectively.

But beware of surprises when you carry these methods over to developing country contexts because they tend to assume Western communication norms. Our research participants felt uncomfortable when asked to articulate their thought processes or to answer “why” questions. To cope with such complications, the methods themselves need to be adapted to context, for example by being more closed-ended and by adopting more conventional semi-structured interview techniques.

Shining New Light on Health Behaviours (Mr Jeffrey Lienert, Saïd Business School and National Institutes of Health)

When people get sick, they do not just make a one-off treatment decision like “I’ll go to a clinic / a private doctor / a pharmacist” and stick to it for the remainder of their illness until they are cured. Rather, they go through several phases. For example, a person might first wait and see if it the illness would not go away by itself, then later decide to buy some painkillers to cope with it, visit a private doctor when things do not get better, then lose hope in modern medicines and visit a traditional healer. We gain a lot of information about people’s behaviour if we collect such data on treatment “sequences.”

Not only is it rare for studies to record treatment sequences at all, but there are also no agreed tools for their analysis. First ground has been broken with sequence-sensitive analyses to produce more accurate typologies of behaviour, but we can go further and apply network analysis techniques to make maximal use of sequential data. More detailed analyses can differentiate between the individual steps, explore whether sequences of behaviour resemble each other across people, and which kind of social network is most decisive for such a resemblance. The downside of these arguably more complex analyses is the technical skill required to perform them, but once these methods become more established, they will be able to us to give more detailed (and realistic!) behavioural profiles of different settings and social groups with revolutionarily new insights for health policy.

Methodological innovation enables easier, more precise, and new ways of understanding human behaviour. That does not necessarily mean “big data” and algorithms. Innovation also arises from new combinations of conventional methods with other established techniques and new technologies. Combining rural health surveys with satellite imagery and accelerometers, social network surveys with cognitive interviewing, and healthcare access data with social network analysis does not just keep the methodological debates in survey research alive. It also enables new research, new questions, and a new view on human behaviour.

This blog entry derives from the authors’ contributions to the ESRC NRCM Research Methods Festival 2018 Conference in Bath, drawing on research from the projects Antibiotics and Activity Spaces (ESRC grant ref. ES/P00511X/1), Mobile Phones and Rural Healthcare Access in India and China (John Fell OUP Research Fund ref. 122/670 and ESRC studentship ref. SSD/2/2/16), and IMMANA Grants funded with UK aid from the UK government (ref. #2.03).

In fast-changing Western healthcare systems, to what extent has the idea of a ‘market’ come into play? And how has this affected and redefined healthcare?

A new book edited by Oxford academics – Marketisation, Ethics and Healthcare: Policy, Practice and Moral Formation – attempts to answer these questions.

The book’s three editors, Dr Joshua Hordern (Faculty of Theology and Religion), Dr Therese Feiler (formerly of the Faculty of Theology and Religion) and Dr Andrew Papanikitas (Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences), talk to Arts Blog about their work, which was highly commended in the recent British Medical Association book awards.

The project forms part of the Oxford Healthcare Values Partnership.

Where did the idea for the book come from?

The idea for the book came out of conversations with doctors and others working in healthcare. We wanted to work together on understanding the changing ethos of the NHS and other health and care institutions nationally and internationally. So we formed a partnership with the Royal Society of Medicine and approached the British Academy for funding. They were excited about the project and awarded funding which was then renewed for a second year to enable us to bring the different strands of our work together in the book. We ran a conference and some workshops to bring people together and set up some conversations.

Core emphases for us and the British Academy have been on involving early career researchers at every stage and on developing enduring partnerships between healthcare practitioners, social science experts and humanities researchers, drawing especially on those working in theology and religion. From the start we wanted to find out the real issues which were shaping the practice of healthcare and then resituate them in ways which would open up new lines of inquiry.

How do you define a ‘market’ in relation to healthcare?

In the book we tend to talk about marketisation and market-type processes operative in health and care. Broadly speaking, we’re talking about mechanisms of packaging, selling and paying for healthcare that are neither state-distribution nor solidarity- or charity-based forms of exchange. These are always mixed in with each other. So the key is to discern by which principles a given policy or system is governed.

Examples perhaps bring this out best – more obvious ones include the changing face of general practice with GPs running pharmacies to the role of private hospitals or doctors offering their services in private practice. But there are other important factors in the mix, including the efforts to create a functioning market in personalised social care through initiatives like personal independence payments; the role of pharmaceutical companies in contributing to and shaping the culture of healthcare; and the significance of diagnosis-related groups as a form of financial coding which has all sorts of intriguing implications for the ethos of healthcare.

What were your aims in carrying out this work?

We asked 12 authors from round the world – influenced by everyone from Marx to free market economics; Christian moral theology to analytic moral philosophy – to think together about the place and influence of market-type processes on policy and practice in healthcare. We wanted to look at institutions as organisations and examine the kind of ethic they embody and depend upon; but we also wanted to examine the way that people’s moral outlook and behaviour are shaped by marketisation processes within those institutions – questions of personal and professional formation. Think of trends like ‘defensive medicine’ which emerge for a variety of factors, but which impact medical professionalism at a deep level. All in all, we wanted to stimulate a conversation about policy, practice and moral formation which is worthy of the deep and existential questions that healthcare raises.

What were the key findings?

There weren’t any findings which all the authors shared. We as editors gave our own views in the epilogue of areas for further research. There’s a further clue, though, in the aphorism in Greek we quote at the start of the book – check it out to see what we think. If we are sincere in our respect for people, which is the ostensible basis for democratic society and healthcare ethics, then money should be a means and people should be ends in themselves. And if we understand how the things that should never be bought and sold connect with the material world, there is a chance they remain visible – even to those who now see the price of everything and the value of nothing.

One overall point which Muir Gray highlighted in the foreword was the question of what will keep money and markets in position to serve health and care rather than distort people’s attention from what matters. A conceptual and policy theme which emerges is the idea of a healthcare covenant, akin to, but distinct from, the military covenant between the people of the UK and armed forces. That’s an idea to be taken into practice in the future. Other approaches include incentives and education.

How can the humanities interact with the medical sciences?

The best way for humanities researchers to make a contribution is in close learning partnerships with medical science researchers and others working in healthcare. Where that is happening, humanities researchers are increasingly in demand for the ways they frame challenges in healthcare. This is partly because of broad cultural transitions in healthcare ecologies which represent a turn from a dependence on a largely or even exclusively biomedical model of conceiving healthcare towards a greater balance between biomedical and social conceptions of healthcare. At the same time, the trajectory towards an ever more high-tech approach to healthcare, with a particular emphasis on the biosciences as key to the UK’s offering to the world post-Brexit, is provoking critical reflection on the very purpose of healthcare. In this context humanities disciplines have the capacity to provide historical perspective, conceptual understanding and other kinds of insight into what helps sustain and restore health for people and communities. Humanities scholars are able to examine and question an entire conceptual edifice that is often taken for granted. Not: ‘How can we solve problem X?’ but rather: ‘Is this even the right way to put the problem?’ When that kind of questioning is done in partnership, everyone may be prompted to try a different path.

All this means there’s a tremendous opportunity for healthcare and humanities researchers to find new and creative ways of understanding the challenges of our time. Humanities researchers are becoming more capable in developing these partnerships and shared agendas with colleagues in healthcare locally, nationally and globally. Mutually beneficial collaborations are enabling more focused and better-informed research which can target the needs and concerns of healthcare organisations. But there remains the strategic need to interweave the agendas of humanities researchers and medical researchers, alongside colleagues in other relevant disciplines, to address challenges which are best tackled in interdisciplinary ways, in partnership with patients, public bodies and private enterprise.

The book's editors express particular thanks to the British Academy for the British Academy Rising Star Engagement Award which made this project possible. They are also grateful for funding from the AHRC (grant AH/N009770/1) and the Sir Halley Stewart Trust.

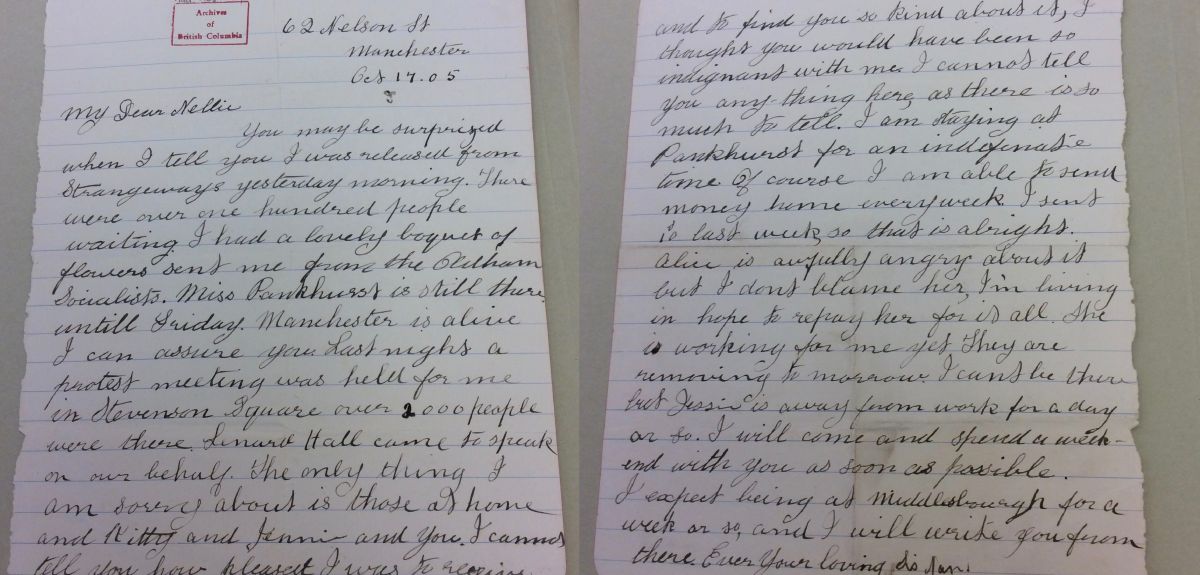

A previously unknown letter from Annie Kenney, the working-class activist who became the first woman imprisoned for campaigning for the vote, is due to go on public display for the first time after being uncovered by Oxford historian Dr Lyndsey Jenkins during her research.

Revealing the personal impact of this iconic political protest, the letter sheds new light on the first act of militant suffrage and is an exciting contribution to this year’s centenary celebrations of the first women gaining the right to vote in Britain.

Written from the Pankhurst family home at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester, the letter was sent from Annie Kenney to her sister Nell in October 1905, informing her that ‘you may be surprised when I tell you I was released from Strangeways [prison] yesterday morning’. The letter offers an intimate insight into the complex and competing emotions that Annie experienced as she left prison. She expresses delight at the impact her unprecedented act had made in the local community and her gratitude at the support from most of her family, but also records how another sister Alice, was ‘awfully angry’ about the incident.

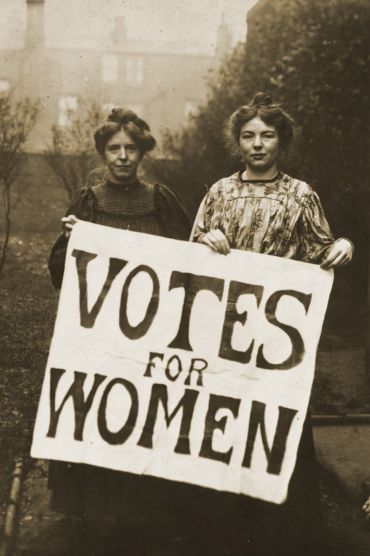

Annie had been sent to jail after she and Christabel Pankhurst had attended a political meeting demanding to know from minister Sir Edward Grey: ‘Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?’ The speaker refused to answer, and the women were thrown out of the hall before both being jailed after Christabel Pankhurst spat at a policeman. The incident is now widely regarded as the first militant action, and the women became instantly famous around the world, attracting huge public sympathy. With the first use of the demand ‘votes for women’ on a placard, the two women created one of the most memorable political slogans of all time, kick-starting a revolution.

The letter has lain unknown for more than a century. Nell Kenney later moved to Canada, and the document was for many years catalogued with general correspondence in the British Columbia Archives in Victoria. It was listed only as part of a collection belonging to Sarah Ellen Clarke, Nell’s full and married name, and, as such, had until now escaped wider attention. It was recently located by Dr Jenkins, who was researching the lives of the seven Kenney sisters as part of her DPhil research in Oxford’s Faculty of History.

Annie Kenney went on to become one of the most prominent leaders of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). After Christabel Pankhurst fled to Paris in 1912, Kenney led the organisation through its most difficult and dangerous years. She served several prison sentences, went on hunger strikes that devastated her health, and eventually spent a year on the run from the authorities as a ‘Mouse’ released under the notorious ‘Cat and Mouse Act’. She was not active in politics after the vote was won for some women in 1918, but remained loyal to the Pankhursts and the WSPU for the rest of her life.

Dr Jenkins said: ‘Annie Kenney was one of the leading suffragettes, but, like other working-class women who played a central part in the fight for the vote, her story and significance is often underestimated and poorly understood. This letter provides new insight into Annie’s private thoughts and feelings at this turning point in the campaign for the vote, as well as showing the warm reception she received from the local community and other activists. This is an exciting and revealing document which deepens our understanding of the battle for suffrage and the women who fought it.’

Annie’s letter shows the close and loving relationship among the Kenney family, whose background was in the mills of Oldham in Greater Manchester, and several of whom went on to have important careers in political, professional and public life. The youngest sister, Jessie, was another leading suffragette who also gained notoriety for her acts of daring: dressing as a telegraph boy to attempt to heckle then Chancellor David Lloyd George and as part of a trio who attacked Prime Minister Herbert Asquith on his holiday.

Nell Kenney, who received the letter, organised a mass protest in Nottingham that narrowly escaped becoming a riot. Two other sisters, Jane and Caroline, also supported the suffragettes’ work, but dedicated their lives to becoming some of the first Montessori teachers in the world, studying with Dr Maria Montessori herself and joining forces with Alexander Graham Bell to pioneer Montessori education in the United States. Meanwhile, their brother Rowland was a leading socialist and the first editor of the Daily Herald, before becoming a pioneer of political propaganda in the First World War.

Author Helen Pankhurst, granddaughter of Sylvia Pankhurst and a leading campaigner for women’s rights, said: ‘One hundred years on from the first women winning the vote, we are still learning more about the remarkable women who led the campaign for us all to have that right. As this important and very personal letter from one sister to another shows, the campaign for suffrage involved high risks and huge personal costs – especially in these early stages when the cause was unpopular and the outcome uncertain. As we mark the centenary of their success, it is right that we remember their sacrifices and remind ourselves that women in the UK and around the world are still taking those risks to achieve true equality for all.’

The letter is on display at Gallery Oldham from 29 September to 12 January as part of the Peace and Plenty? Oldham and the First World War exhibition. It is on loan from the British Columbia Archives in Victoria, Canada.

Oldham Councillor Hannah Roberts, Elected Member Champion for the Suffrage to Citizenship Programme, said: ‘I am delighted that this letter has come to light, and how great that we get to see it being exhibited in the birthplace of Annie Kenney herself. We are very lucky to have it on loan from Canada. It will make a lovely addition to the suffrage artefacts already held by Gallery Oldham, and I hope people will go along to see this significant piece of Oldham’s suffrage history.’

Professor Jack Lohman, Chief Executive of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives, added: ‘We are so pleased to be able to share this poignant letter with Gallery Oldham and its visitors, and to add something so personal to the important story of the suffrage movement. The British Columbia Archives hold thousands of stories that connect us around the world, and Annie Kenney’s letter is an outstanding example of our shared histories.’

Annie’s letter

62 Nelson Street,

Manchester

Oct 17.05

My Dear Nellie

You may be surprised when I tell you I was released from Strangeways yesterday morning. There were over one hundred people waiting. I had a lovely boquet (sic) of flowers sent me from the Oldham Socialists. Miss Pankhurst is still there untill (sic) Friday. Manchester is alive I can assure you Last night a protest meeting was held for me in Stevenson Square over 2000 people were there Lenard (sic) Hall came to speak on our behalf the only thing I am sorry about is those at home and Kitty and Jennie and You, I cannot tell you how pleased I was to receive your letter and to find you so kind about it, I thought you would have been so indignant with me I cannot tell you anything here as there is so much to tell. I am staying at Pankhurst (sic) for an indefinite time of course I am able to send money home every week. I sent it last week so that is alright. Alice is awfully angry about it but I don’t blame her, I’m living in hope to repay her for it all. She is working for me yet, they are removing to morrow. I can’t be there but Jessie is away from work for a day or so. I will come and spend a weekend with you as soon as possible. I expect being at Middlesbourgh (sic) for a week or so, and I will write you from there,

Ever Your Loving Sis

Nan.

Professor Dominic Wilkinson, Professor of Medical Ethics at the University of Oxford and a Consultant in newborn intensive care at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, discusses the ethical issues around providing medical treatment for children when parents and doctors disagree.

The fraught life and death cases of Charlie Gard and Alfie Evans, reached global attention in 2017 and early 2018. They led to widespread debate about conflicts between doctors and parents, and about the place of the law in such disputes. Changes to the law in response to these high-profile cases are currently being debated in the House of Lords.

In 2016, Professor Savulescu of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics wrote an editorial for the Lancet medical journal strongly criticizing the court’s decision, and arguing that Charlie Gard should be allowed to travel to America for experimental treatment. He argued that Donald Trump and the Pope were right to support Charlie’s family. In the same issue of the Lancet, I took the opposing view, supporting Charlie’s doctors, and arguing that Charlie should be allowed to die. Professor Savulescu and I are colleagues and long-time collaborators.

Over the ensuing months, while the appeals for Charlie Gard were heard in the courts, Savulescu and I conducted a vigorous debate in academic journals and in the media about the rights and wrongs of the Gard case. Over time, we found areas of agreement, as well as areas of reasonable disagreement.

In a newly published book, Professor Julian Savulescu and I examine the ethics of medical treatment disputes for children, as well as outlining our own professional disagreement on the Gard case. At one level, this is a rigorous analysis of the rights of parents, the harms of treatment, and the vital issue of limited resources. From opposite sides of the debate about treatment for Charlie Gard, we provocatively outline the strongest arguments in favour of and against treatment. We also outline a series of lessons from the Gard case and propose a radical new ‘dissensus’ framework for future cases of disagreement.

This case also illustrates some of the distinctive and challenging features of ethical debate in the 21st century. We have shown that it is possible for those who find themselves at opposite ends of an issue to find common ground. Indeed, disagreement about controversial ethical questions is both inevitable and desirable.

There is a need for sensitive, rational debate within our community about how to fairly address disagreements about treatment between health professionals and families. That debate cannot, now, help Charlie Gard or Alfie Evans. It can, though, help current and future children with serious illnesses.

It can support their families to access desired treatment, within limits. It can help health professionals to be able to advocate for the best interests of their patients. It can help doctors to maintain relationships with families (even if not always seeing eye to eye). It can help society to understand what is at stake, why these disagreements are so difficult, so vexed, and so inevitable.

In difficult ethical debates, there is sometimes a desire to reach consensus or agreement on the right thing to do. But that can be a mistake. On questions of deep ethical values, there will always be disagreement. We need to embrace dissensus, not consensus. We should be prepared to disagree

‘Ethics, conflict and medical treatment for children: from disagreement to dissensus,’ is published by Elsevier.

Professor Julian Savulescu is Professor of Practical Ethics in the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics at the University of Oxford. Professor Dominic Wilkinson is Professor of Medical Ethics at the University of Oxford and a Consultant in newborn intensive care at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford. Wilkinson and Savulescu are medical doctors as well as experts in medical ethics.

New research published in Nature Ecology & Evolution from the Department of Zoology at Oxford University aims to show how big data can be used as an essential tool in the quest to monitor the planet’s biodiversity.

A research team from 30 institutions across the world, involving Oxford University’s Associate Professor in Ecology, Rob Salguero-Gómez, has developed a framework with practical guidelines for building global, integrated and reusable Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBV) data products.

They identified a ‘void of knowledge due to a historical lack of open-access data and a conceptual framework for their integration and utilisation'. In response the team of ecologists came together with the common goal of examining whether it is possible to quantify, compile, and provide data on temporal changes in species traits to inform national and international policy goals.

These goals, such as the Sustainable Developmental Goals (SDG) of the United Nations, have become fundamental in shaping global economic investments and human actions to preserve and protect nature and its ecoservices.

Essential Biodiversity Variables (EBVs) have been proposed as ideal measurable traits for detecting changes in biodiversity. Yet, the researchers say, little progress has been made to empirically estimate how EBVs in fact change through time at the regional and global scales.

To overcome this, Rob Salguero-Gómez and his international collaborators have developed a framework with practical guidelines for building global, integrated and reusable EBV data products of species traits. This framework will greatly aid in the monitoring of species trait changes in response to global change and human pressures, with the aim to use species trait information in national and international policy assessments.

Salguero-Gómez says: 'We have for the first time synthesised how species trait information can be collected (specimen collections, in-situ monitoring, and remote sensing), standardised (data and metadata standards), and integrated (machine-readable trait data, reproducible workflows, semantic tools and open access licenses).'

This latest review provides a perspective on how species traits can contribute to assessing progress towards biodiversity conservation and sustainable development goals. The researchers believe that big data is one of the keys to address the global and societal problems from security food, to preventing ecoservice loss, or effects of climate change.

They say that the operationalization of this idea will require substantial financial and in-kind investments from universities, research infrastructures, governments, space agencies and other funding bodies. ‘Without the support of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, NERC, Oxford, and the open-access mentality of hundreds of population ecologists, our work with COMPADRE & COMADRE would not have been possible,’ says Salguero-Gómez.

The integration of trait data to address global questions in ecology, evolution, and conservation biology is one of the main themes in Salguero-Gómez’ research group, the SalGo Lab.

This work was funded primarily by the Horizon 2020 project GLOBIS-B of the European Commission.

- ‹ previous

- 65 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria