Features

Although the vacation is upon us, Oxford's colleges are still busy with students on the UNIQ summer school. UNIQ aims to give high achieving state school students from socio-economically and educationally disadvantaged backgrounds a taste of what academic life at Oxford is like.

The results of UNIQ graduates are impressive. Of the 544 students who had previously taken part in UNIQ who applied to Oxford in 2013, 237 received offers – a success rate of 43.6% in comparison to 20% for the average applicant. This year more than 1,000 students will take part in the scheme.

This year's History summer schools were hosted by TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, and students studied 'Race and Protest in Modern America and Britain' and 'Gender, Identity and Change'.

Students taking these courses heard lectures from leading historians and even got the chance to meet British and American civil rights activists and hear about their experiences. Students took part in group discussions and did individual research to produce an essay which was discussed in an Oxford-style tutorial at the end of the week.

Blogs written by students who attended last week’s programme, which have been posted on the TORCH website, indicate why UNIQ has been so successful.

'My essay was a discussion on the benefits of comparing the American and British Civil Rights movements together,' said Martha Homfray-Cooper, a student at Stratton Upper School in Bedfordshire. 'This led me to analysis of primary sources such as newspaper reports, wrestling with historians’ opinions and the construction of a thoughtful argument.'

Martha added: 'The most helpful part of the week was the tutorial discussing the essay. This allowed me to develop my argument, discuss the relevance of sources and dig deeper into the history of civil rights. Also, having access to the Bodleian Library was a privilege and made the research all the more fascinating.

'The highlight of the experience for me was the talk from the activist Eric Huntley,’ said Rachael Beaty, a student at Queen Elizabeth Grammar School in Penrith. 'Before the summer schools, I had never come across the idea of a 'British civil rights movement', so to hear about it first hand from Eric was incredible.

'His perceptive nature towards racism in the late twentieth century was remarkable, to give such a positive light on Britain despite the hardship the country gave him was extremely humbling.'

Students and academics at Oxford who taught on the course were impressed with the students. 'I speak for all the graduate tutors when I say that the students' intelligence, confidence, and passion for History made them a pleasure to have in the discussion groups and tutorials,' said Michael Joseph, a third year History student who was a mentor on the 'Race and Protest' programme.

'Although they won't believe me, one of my favourite parts of the week was marking their essays! I was so impressed by how they had dealt with all the new factual information and the difficult, unfamiliar concepts they had encountered.'

'This year's summer school brought together activists, academics, current students and the UNIQ students to explore, in depth, new ways of thinking about the vitally important subject of the history of race equality and protest,' said Dr Stephen Tuck, director of TORCH.

'We all learnt from each other, and I think, were all excited about the opportunities that studying history and higher education provide.'

The UNIQ website has information for prospective applicants to next year’s programme.

The parts of the world that would benefit most from research on the biggest health problems – like malaria, HIV, maternal health problems and diarrhoea – are also the regions where that research is most lacking.

Crucial evidence is not being generated because many doctors and nurses on the ground lack research experience and support. Effort is also regularly duplicated or conducted using different criteria in different territories and studies. Sometimes studies fall by the wayside from lack of simple resources and guidance on best practice. The development of better and more local research in the area of global health is crucial.

Joby George, a research nurse in Medanta, India, says, 'The initial step in conducting research is in understanding the research process, and this can be quite a barrier to getting people to start doing research. Nurses, who are the pillars of healthcare, often have research questions they want to work on but due to a lack of resources and a high workload they sometimes just want to treat patients and go home. Nurses therefore don’t pursue research.'

This is where the Global Health Network comes in.

Developed and conceived in Oxford, it's a free online platform for health workers and researchers around the world to exchange knowledge, share methods and form collaborations. Since its launch in 2011, the site has had over 260,000 visits from people in 150 countries, thousands of resources have been accessed, and over 20,000 free eLearning modules have been taken by those who otherwise may not have access to such training.

Today, the network has launched a new toolkit designed to help researchers conduct rigorous health studies. The Global Health Research Process Map is an open-access online resource which aims to provide the guidance, training and support that researchers need to run their own studies, wherever they are in the world.

Oxford University's Dr Trudie Lang is director of the Global Health Network, and works in the Tropical Medicine division of the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine. She says: 'We're very excited to launch the Global Health Research Process Map because this will make the process of initiating global health research simpler, and the results more accurate and more locally relevant.

'We've spoken with many researchers around the world who have been looking for a tool like the Global Health Research Process Map – to let them focus on their work instead of spending their crucial research time duplicating effort and searching for advice.'

The Process Map is the product of four years of best practice gathered and refined by those using the Global Health Network platform.

It is a tool that centralises the information and resources necessary to carry out rigorous and effective global health studies, and takes people through the process of conducting accurate research, step-by-step. This is important because there is a lot of evidence that shows that locally-led research rarely happens in low-income settings because health workers lack research skills and any access to training and support.

Researchers also have the opportunity to exchange ideas with others along the way, aiding collaboration and allowing everyone to learn from the experiences of previous studies.

'The Process Map is also a democratic tool. Research conducted in developing countries needs to be to the same standards of that conducted in Western countries and everywhere else around the world,' says Henok Negussie of Brighton & Sussex Medical School, who is coordinating a trial in northern Ethiopia. 'I believe the Process Map provides guidance for researchers to standardise the process that they need to consider, and ensures that high-quality research is conducted.'

Morenike Ukpong, who works on HIV prevention as an associate professor at Obefemi Awolowo University in Nigeria, agrees. 'I really like the concept of the Process Map,' she says, ‘it shows the complex – yet interactive – nature of developing a clinical trial but in a way that’s simple to navigate. I haven’t seen anything like this before. I’ll be using it as a teaching platform, and also as a networking platform.’

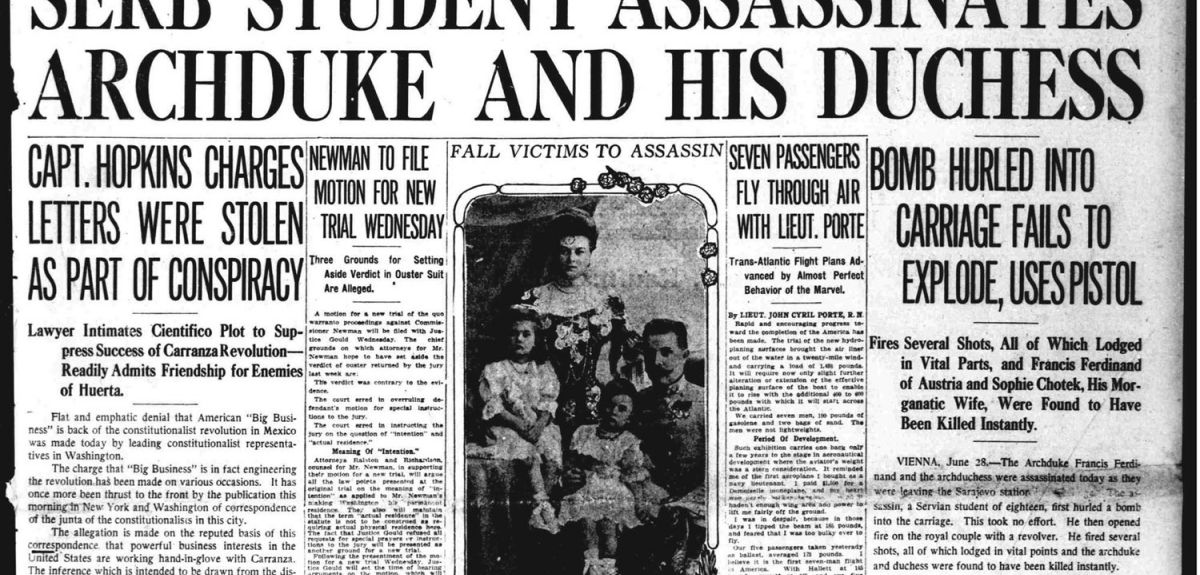

Did you miss the tenth episode of Margaret MacMillan's radio series about the road to World War One yesterday? Well don't worry because there are 33 more to come.

From 27 June to 8 August Margaret MacMillan, professor of international history at Oxford University and Warden of St Antony’s College, is presenting ‘Day By Day’, a series of 43 four-minute programmes which will be aired daily at 4.55pm on BBC Radio 4.

Each episode explores sources which relate the events of that day, one hundred years earlier, beginning with Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s visit to Bosnia.

Professor MacMillan has also recently brought out a book on the same subject, called The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914.

'When I started to write the book, I was trying to think of a way to look at a subject which has been gone over so much. There's always a danger, when looking at the causes of the First World War, that we can see all the things that were leading up towards the war in 1914,' Professor MacMillan said.

'Because we can see them, we tend to think that the war was bound to happen. The more I think about it, the more I think that it wasn't bound to happen.'

Professor MacMillan added: 'Both my book and the BBC radio series are intended to help people understand the world of 1914 from its political and social structures to the ideas and values of Europeans then. We should not assume that the war was inevitable but ask rather why did the peace not last.'

You can listen to the series so far here.

John Humphrys, the presenter of Radio 4's Today programme, can strike fear into prime ministers and CEOs. But he was no match for Oxford University classicist Cressida Ryan in an interview this week.

In an interview to mark Grammar Day Mr Humphrys asked whether English words which sound as if they are derived from Latin should take Latin plural endings, for example bacteria rather than bacteriums and referenda rather than referendums.

Dr Ryan said: 'There are three issues here: what is correct Latin? What is correct English? What is the relationship between those two? It depends whether you are using something as a Latin word you have borrowed, or if you are choosing to use it as an English word.'

Dr Ryan pointed out that English is a living, flexible language that can accommodate different ways of expressing the same word. She said: ‘People in particular technical business will use words in a particular way for them that might different from people in other parts of the country because English is a language which has regional dialects, temporal dialects, and describes different things in different ways.

‘So it is fair to use bacterium in the singular form. But if you wanted to talk about a class of things then bacteria sounds perfectly fair as a collective noun.

'The more Latin you do at school or university, the more you realise how quickly linguistic change happens and how dynamic languages are.'

Dr Ryan pointed out that the collective wisdom about how a word should correctly be written is often wrong. 'For 'syllabus', actually the plural in Latin would still end in 'us' but most people think it would be syllabi,' she said. 'In Italian, panino would be the singular of panini, but in the UK we use panini as the singular when ordering in a restaurant.'

She then added: 'There's one other aspect to this, which is that bacteria is in fact singular and a Greek word.'

To the sound of background laughter in the studio, Mr Humphrys could only reply: 'Ah. You’ve silenced me.'

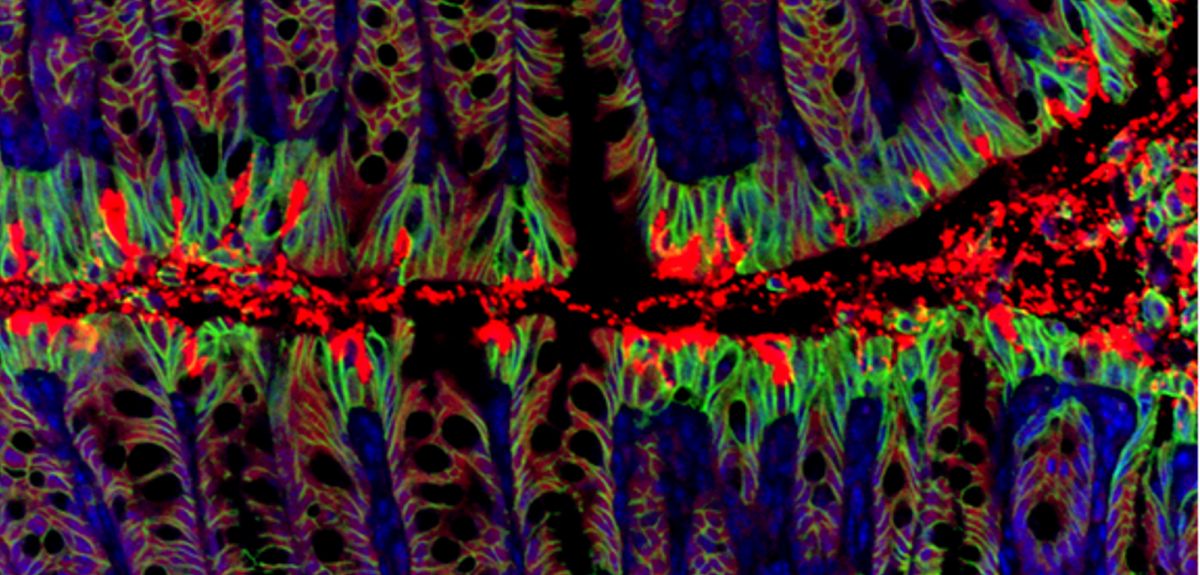

There's an odd-looking Perspex box sat on a workbench in one corner of Professor Fiona Powrie's lab. It's not much to look at. It's a see-through box with flasks inside, in which bacteria are grown at body temperature – as is done in thousands of molecular biology labs around the planet. But there's a glove box on the front with seals to prevent the outside air getting in. That's because these bacteria are grown under oxygen-free conditions, the same conditions as are found inside your belly.

'The gut is the wild west of the body,' says Dr Claire Pearson, a postdoc in the Powrie lab in the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine. 'There's food, bacteria and foreign things, but how does the gut distinguish the good, the bad and the ugly?'

In terms of numbers of cells in our bodies, we're actually more bacteria than we are human, Claire explains. Many bacteria in the gut are really helpful for digesting food. We need this flourishing ecosystem of different bacteria populating our insides. But when it comes to "bad" bacteria, it's immune cells including some called T cells that act as sheriff to take down those invasive strains and run them out of town.

We might be largely unaware of this showdown taking place in our insides, but Professor Powrie and her lab colleagues are taking the gunslinging duel between our immune cells and the bacteria colonising our colons to the Royal Society’s annual Summer Science Exhibition that begins today.

The exhibition sees large numbers of visitors each year, from school groups to tourists, and makes the best of cutting-edge British science fun for all.

On the Powrie lab's stand, you’ll be treated to an interactive exhibit where you can build your own gut on a giant wall, complete with fluffy bacteria. There'll be a shoot 'em up game to blast the bad bacteria out of the gut, but not the good bacteria. You'll be able to look at your own cells under the microscope and spot all the bacteria living on you, all taken from a swab inside your mouth. And, er, bringing up the rear, there'll be endoscopy videos so it's possible to see the difference between an inflamed bowel and healthy intestines.

'We need to have a balance between our immune response and the bacteria in our gut,' says Claire. 'When this balance breaks down, it can lead to inflammation and disease. This is what we see in inflammatory bowel disease.'

Understanding this balancing act is what the Powrie lab is interested in: How are the complex interactions maintained between immune cells, tissues in the gut and the diverse bacteria living in the gut? And what leads immune responses to spiral out of control and damage the intestinal tissue?

This isn't just an academic pursuit. Their Translational Gastroenterology Unit is linked to the John Radcliffe hospital, allowing studies with human tissue samples and clinical studies with patients. New insights that lead to improved treatments for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) could make a great difference to patients.

IBD is thought to affect around 261,000 people in the UK. The bowels become swollen and sore and common symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhoea (sometimes with blood), abscesses, weight loss and tiredness. There are two types – Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis – but both are chronic, incurable diseases that flare up unpredictably, making them very difficult conditions to live with. While people experience different severities of disease, in many the condition progresses and eventually needs surgery to remove parts of the intestine.

Professor Powrie played an instrumental role in identifying the role of a subset of immune cells called regulatory T cells (Treg cells), and her lab continues to work on these cells.

'Regulatory T cells are key for harmony in the gut. They police immune cells to keep their response under control, releasing factors that suppress the T cell response,' explains Claire Pearson. 'This balance can break down in IBD.'

The group continues to be interested in the role of different immune cell types in disease, how Treg cells function through the compounds (cytokines) they secrete, and how that cytokine secretion varies in different sites in the gut.

Understanding all the cellular processes that are involved could pinpoint new targets for drug development, says Claire.

The Royal Society’s Summer Science exhibition opens to the public today and runs until Sunday.

- ‹ previous

- 166 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?