Features

Luminous galaxies far brighter than our Sun constantly collide to create new stars, but Oxford University research has now shown that star formation across the Universe dropped dramatically in the last five billion years.

The research, co-led at Oxford by Dr Dimitra Rigopoulou and Dr Georgios Magdis from the Department of Physics, showed that the rate of star formation in the Universe is around 100 times lower than it was five billion years ago. They also showed that some luminous galaxies could create stars on their own without colliding into other galaxies.

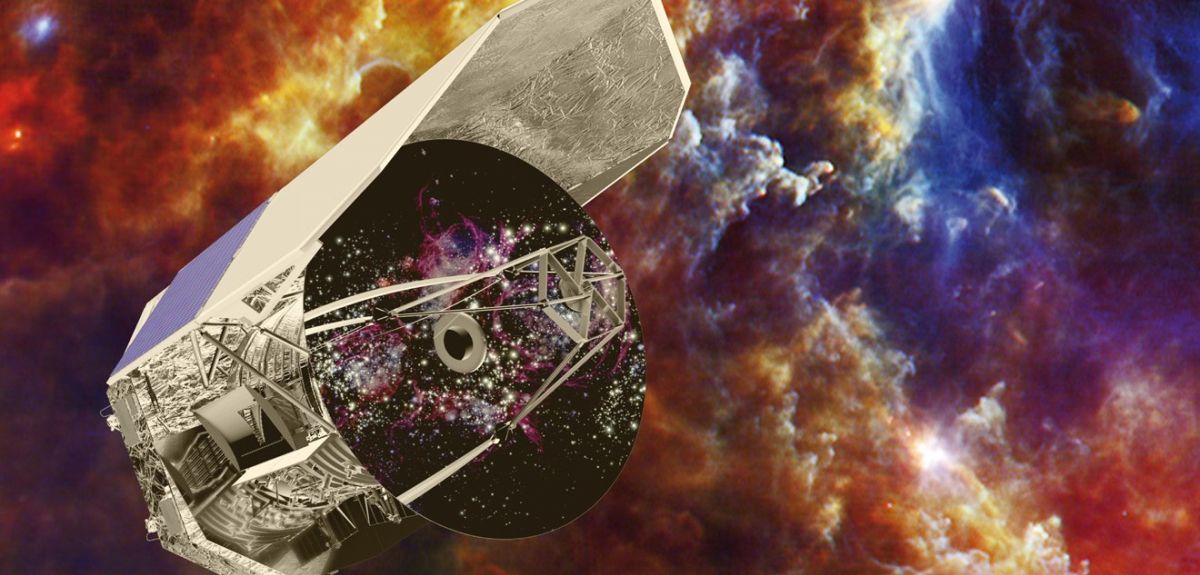

The findings, published in the Astrophysical Journal, suggest that most of the stars in our universe were born in a 'baby boom' period five to ten billion years ago. The observations were made using the European Space Agency's Herschel Space Observatory.

I asked lead author Dr Rigopoulou to explain the research and what it tells us about the birth of stars.

OxSciBlog: What has changed in the last five billion years?

Dimitra Rigopoulou: There is clear evidence that the galactic-scale physical processes that initiate the formation of stars in the most luminous galaxies in the Universe have changed. Locally, luminous galaxies that produce a large volume of stars are almost always associated with galaxy interactions or merging. When galaxies collide, large amounts of gas are driven into small, compact regions in the galaxies causing stars to form. This process results in a highly efficient conversion of gaseous raw materials into stars. However, we found that many galaxies were able to form stars without colliding a few billion years ago.

OSB: Why is this important?

DR: We know that the majority of the stars in our Universe were born in massive, luminous galaxies. Our results change our understanding about how stars were formed in these systems. Consequently, our view about the way the majority of stars formed in our Universe must change.

OSB: Why is it surprising that non-colliding disk galaxies can create stars?

DR: Normal disk galaxies are unperturbed systems that undergo a slow and steady evolution. So, by discovering normal disks with very high star formation rates we have uncovered a fundamental change in the galactic-scale process of star formation in the most efficient star-forming galaxies of our Universe.

OSB: What results surprised you the most and why?

DR: Over the last decade there have been various lines of evidence suggesting that in the early Universe around ten billion years ago, luminous galaxies were quite different from what we observe in the present day.

To our surprise, we found that this change already occurred less than five billion years ago, suggesting that the changes were very rapid and did not happen over long timescales. We measured ionised carbon, which is produced when the gas in the galaxy cools down and collapses initiating the formation of stars. The ionised carbon levels from luminous galaxies five billion years ago were very similar to those from ten billion years ago but completely different to today's galaxies. Something important must have happened to change galaxies' behaviour to what we see today.

OSB: Do we know why galaxy behaviour is changing?

DR: We think there are two main factors responsible for the change in the behaviour of galaxies: one is the amount of gas that is available to them and the other is the gas 'metallicity', the proportion of matter made up of chemical elements other than hydrogen and helium . As galaxies get older, they use up their gas to make stars so they run out of the raw material needed to create more stars. The availability of large gas reservoirs means that some galaxies can make stars efficiently without the need of interactions to trigger the star forming activity, as happens in local galaxies. Metallicity, on the other hand, is very closely related to star formation so a change in the specific make up of the gas can have a huge impact on the way star formation proceeds and hence affect a galaxy’s behaviour.

While our results have highlighted these important changes in the way galaxies form their stars as they turn older we now have to follow these leads and firmly establish these points of change in the fascinating lives of these luminous infrared galaxies.

Dr Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, is among this term's Humanitas Visiting Professors at Oxford University.

Dr Williams will be giving two lectures in his capacity as Humanitas Visiting Professor in Interfaith Studies, as well as taking part in an 'in-conversation' event with Jon Snow.

Acknowledged internationally as an outstanding theological writer, scholar and teacher, Dr Williams has been involved in many theological, ecumenical and educational commissions. He has written extensively across a wide range of related fields of professional study, including philosophy, theology (especially early and patristic Christianity), spirituality and religious aesthetics. He has also written throughout his career on moral, ethical and social topics and, after becoming archbishop, turned his attention increasingly on contemporary cultural and interfaith issues.

Dr Williams' programme begins on 24 January with his first lecture ('Faith, Force and Authority: does religious belief change our understanding of how power works in society?') followed by the in-conversation event. He will then give his second lecture ('Faith and Human Flourishing: religious belief and ideals of maturity') on 29 January.

Also visiting Oxford this term is General Michael Hayden, as Humanitas Visiting Professor in Intelligence Studies.

General Hayden is the former director of the National Security Agency and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). As director of the CIA, General Hayden was responsible for overseeing the collection of information concerning the plans, intentions and capabilities of America's adversaries; producing timely analysis for decision makers; and conducting covert operations to thwart terrorists and other enemies of the United States.

Before becoming director of the CIA, General Hayden served as the country's first Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence and was the highest-ranking intelligence officer in the armed forces. He currently serves as a principal at the Chertoff Group, a security and risk management advisory firm, and as a Distinguished Visiting Professor at George Mason University.

General Hayden will be lecturing on 10 and 12 February with talks titled 'My Government, My Security and Me' and 'Terrorism and Islam's Civil War: Whither the Threat?' respectively.

Humanitas is a series of Visiting Professorships at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge intended to bring leading practitioners and scholars to both universities to address major themes in the arts, social sciences and humanities.

Created by Lord Weidenfeld, the programme is managed and funded by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue with the support of a series of generous benefactors and administered by the Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

What's behind the engines that keep planes in the air?

In a new animation launched today, Oxford University engineers take viewers on a tour around the modern jet engine, exploring the qualities that enable fast and efficient air travel.

The animation, 'Jet Plight', is the latest in a series of videos from Oxford Sparks, a web portal giving people access to some of the exciting science happening at Oxford University.

It follows the adventures of Ossie, a friendly green popsicle who has previously been on a spin around the brain, met a rogue planet and negotiated a volcano's plumbing system, as well as investigating heart attacks, the coldest things in the universe, and the Large Hadron Collider.

I caught up the project's scientific adviser, Professor Peter Ireland of Oxford University's Department of Engineering, to find out more about the science behind the animation.

OxSciBlog: What makes jet engines such a fascinating area of research?

Peter Ireland: Many things - for example, the way in which engines are designed to deal with extremes of pressure, temperature and rotational speeds. The gas flow inside the turbine needs to be precisely controlled and this means we need to understand the way it behaves. We use sophisticated computer models to predict these flows and experiments to understand the flow physics.

OSB: What made you decide to get involved with Oxford Sparks?

PI: I want people to see that engineering is an exciting, important subject and to encourage more schoolchildren to consider it as a career. There’s a real shortage of women going into engineering, so if this animation causes even one girl to consider a career in engineering then I’d consider it a success. There are fantastic opportunities for young people in this country, with a great demand for engineering graduates. Aerospace manufacturers are always looking to recruit new engineers to fulfil their ever-growing order books.

OSB: Why is it so important to make blades from a single crystal of metal?

PI: If you steadily try to stretch most metals, over time they extend slowly - or creep. Creep gets much easier at high temperatures, and the way a blacksmith works high temperature steel is a good example of how metal deformation gets easier with heating. Most metals are made of tiny individual crystals, and creep often occurs at the boundaries between crystals. Creep is reduced if the metal part is made of a single crystal.

OSB: What makes Oxford's turbine test facilities so special?

PI: Our research has focussed on understanding the way in which engine parts perform - especially the turbine. Over the last 40 years, we have perfected computer methods and experiments to understand and predict the performance of this amazing part of the engine. Our facilities allow us to study the heat transfer in great detail and to simulate real conditions using scale models. There are special equations in what we call ‘dimensionless groups', where certain parameters behave the same at all scales. For example, you could put an Airfix-size Concorde in a Mach 2 wind tunnel and see the same patterns of pressure and shock structures that you would see in the real thing – although you might need to strengthen the model if it’s made from thin plastic!

OSB: What impact might your group's work have on making 'greener' engines?

PI: We have helped to make the engine more fuel-efficient by reducing inefficiencies caused by aerodynamic losses and cooling air. The ultimate aim of most of our research is to reduce CO2 emissions from jet engines.

OSB: Do you expect to see any major changes in jet engines over the next few decades?

PI: Yes. The engine architecture used for passenger Civil Aircraft, such as the Boeing 787 and Airbus 380, has been stable for many years. I think engine configuration will change significantly for future generations of aircraft. We can make engines more efficient by increasing the proportion of air passing through the propellers outside of the core jet intake, called the ‘bypass ratio’. However, these efficiency gains are reduced as we need to build ever-larger casings, called ‘nacelles’, around the propellers that add weight and drag. A new generation of engines called ‘open rotor’ are designed to work without needing nacelles, offering greatly improved efficiencies. I look forward to seeing these technologies develop in years to come.

Reviving a gene which is 'turned down' after birth could be the key to treating Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), an incurable muscle-wasting condition that affects one in every 3,500 boys.

Boys with DMD have difficulty walking between the ages of one and three and are likely to be in a wheelchair by age 12. Sadly, they rarely live past their twenties or thirties.

For the past 17 years, Professor Dame Kay Davies and Professor Steve Davies at Oxford University have been working on treatments for the condition, which is caused by a lack of the muscle protein, dystrophin.

In recent months they have found a number of new groups of molecules which can increase the levels of utrophin, a protein related to dystrophin. Greater levels of utrophin can make up for the lack of dystrophin to restore muscle function. They have worked with Isis Innovation, Oxford’s technology transfer arm, to strike a deal with Summit, a drug development company with a focus on DMD.

'Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a devastating muscle wasting disease for which there is no known cure,' said Professor Kay Davies. 'These boys all still have the utrophin gene – and that’s what we’re taking advantage of. In adult muscle, utrophin is present in very low amounts, and we aim to increase the amount to levels which will help protect the muscle in these boys.

'If this approach, called utrophin modulation, really works as we hope, we could treat these boys very early on, increase their quality of life and length of life. They would walk for longer.

'This is a disease that really needs effective treatment – it takes many families by surprise because of the high new mutation rate which occurs in dystrophin protein such that boys with no family history of the disease can be affected.'

The Oxford team have been working with Summit, an Oxford spin-out company, to develop their first drug for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, SMT C1100. In 2012, SMT C1100 successfully completed a Phase 1 trial which showed the drug could safely circulate through the bloodstreams of healthy volunteers. It is now about to enter clinical trials in people with DMD.

Professor Kay Davies said: 'In our ideal world the first molecule we developed with Summit plc, SMT C1100, will have a beneficial effect in these patients. But although SMT C1100 looks promising, we asked ourselves - can we find other drugs that might do even better?'

The new deal will see a research collaboration formed between the University of Oxford and Summit to further the development of the new set of molecules.

Professor Steve Davies said: 'We want to ensure that this utrophin modulation therapeutic approach has the best chance of success in the shortest time for treating Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. We are delighted to join forces with Summit plc in developing, alongside first in class SMT C1100, these back-up and potentially best in class candidates.'

Tom Hockaday, Managing Director of Isis Innovation, said: 'Isis is delighted to support Professors Kay Davies and Steve Davies in this vital work. Having a number of potential drug candidates in development greatly increases the chances of reaching the ultimate goal, which is to successfully treat this incurable disease.'

Glyn Edwards, Chief Executive Officer at Summit, said: 'The alliance provides access to differentiated classes of utrophin modulators, potentially with new mechanisms, to complement our clinical candidate SMT C1100 while also establishing a strong drug pipeline for the future. Importantly, the alliance cements our long-term relationship with two scientific leaders at the University of Oxford.'

Michael Faraday or Michael Flatley? Science or dance? The latest Science video competition shows that the two go hand in hand...

A creative video on sperm competition [watch the video], which sees swimming cap-clad sperm chasing a water-borne egg through a lake, scooped top prize in Science magazine's 2013 Dance your PhD contest.

The film was created by Dr Cedric Tan from Oxford University's Department of Zoology, who has previously won the 2012 NESCent Evolution Video Contest and the Biology category of Science's 2011 Dance your PhD contest.

I caught up with Cedric to find out how he took his ideas from the lab to the lake...

OxSciBlog: Could you tell us a little more about the concepts shown in the film?

Cedric Tan: There were two main ideas in this film. First, a male invests more sperm in the females that have mated with his brother. This was an interesting finding in the red jungle fowl where females mate with multiple males, creating episodes of competition between sperm of different males. Second, the female ejects a higher proportion of sperm from the brother of the first male mate and favours the sperm of the non-brother, facilitating a higher fertility by the non-brother's sperm.

OSB: Why are non-brother sperm more successful, and are there evolutionary reasons for this?

CT: The non-brother sperm is probably more successful as a result of female preference and ejection of a larger proportion of sperm from any of the brothers. We are not sure why females behave as such but a probable reason is that the females are mating with the male that is different from the brothers in order to increase the genetic diversity of the offspring.

OSB: What challenges did you face trying to explain these concepts through dance?

CT: A major challenge is definitely the fact that dance is a non-spoken art and we had to use our bodies to convey the scientific idea. However, through movements inspired by chickens and sperm, we were able to illustrate sexual behaviour of the chicken and some interesting characteristics of sperm biology.

OSB: Could you tell us a bit about the accompanying music?

CT: The two original music and lyrics pieces were written by Dr Stuart Wigby, my former supervisor. The first piece 'Animal Love' is about the variety of sexual behaviour across different animal species. The second piece 'Scenester' is a piece about a girl who keeps changing her ways and males trying to keep up with her, which is especially apt for illustrating sperm competition.

OSB: How long did it take to plan, choreograph, shoot and edit?

CT: This idea was conceived last summer after I finished the previous video on 'Less Attractive Friends'. However I only started in June 2013 to plan, with the help of my Producer Sozos Michaelides and co-producer Kiyono Sekii. Choreography and training of the dancers was done with my co-choreographer Hannah Moore and lasted 4 weeks. Choreography came along quite readily as I was working simultaneously on my field experiments, in which I was deriving inspiration from the chickens and the sperm under the microscope. Hannah also worked very closely with me on synthesising sperm and chicken movements with sports actions.

After the intense training and for the following three weeks, the Director of Photography, Xinyang Hong, shot the dancing at various places, from Port Meadows to Hinksey Lake. I took about 3 weeks to edit the videos and that was a pain but looking at the outcome, I must say it was all worth it!

OSB: Do you have any plans for another video next year?

CT: Yes of course! It will sexier, stickier and sizeably bigger, and in the style of a musical. But the idea is a secret... I am already excited about creating this new piece!

OSB: Finally, how did you convince so many people to dress up as sperm and jump into a freezing lake?

CT: It took lots of bribing with food. Kiyono also religiously brought flasks of hot drinks for the dancers every time we had pool/lake filming. As for the costume, many of the sperm complained a lot, I just had to buy more food.

The video was funded by Green Templeton College, Oxford, The Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology and the European Society for Evolutionary Biology.

- ‹ previous

- 176 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria