Features

What do you get when you cross an artist with a scientist?

It's not a trick question, but the basis of a project called Silent Signal, which brought together six animation artists and six leading biomedical scientists, to create experimental animated artworks exploring new ways of thinking about the human body.

Oxford University's Professor Peter Oliver worked with artist Ellie Land, talking about the links now being discovered between sleep and mental health. The result is a five minute animation titled Sleepless. Its rhythm is inspired by the circadian cycle and displays visual icons rooted in the science of sleep, whilst featuring the voices of a group of mental health service users who share their experience of disrupted sleep/wake patterns.

That disruption is the target of Peter’s research. He studies gene function in the brain and the consequences of gene dysfunction in disease, with focus on the relationship between sleep and mental health.

Watch the animation below or find out more at: http://www.silentsignal.org/Collaborations/sleepless/

Scientists have long known that our bodies need to control the communities of bacteria in the gut to prevent a beneficial environment from turning into a dangerous one. What hasn't been known is how we do this.

Now, Oxford University researchers have proposed a clever solution to the problem: make good bacteria sticky so they don't get lost. The key to this is for a host to target good bacteria over bad ones – potentially via the immune system, which produces highly-specific adhesive molecules called immunoglobulins (specifically 'IgA') that coat the bacteria in the gut.

The research is published in the journal Cell Host and Microbe.

Co-lead author Kirstie McLoughlin, of the Department of Zoology at Oxford University, said: 'We carry with us vast communities of bacteria that live on us and inside us, particularly in our intestines. These bacteria perform many functions for us, such as breaking down our food, helping our immune system develop, and protecting us from pathogenic bacteria. These are what are often known as the "good" bacteria: a diverse set of beneficial species that improve our health and wellbeing.'

These bacteria perform many important functions for us, and if the wrong species take hold inside us the results can be dramatic. An upset stomach is a common result of a pathogen such as Salmonella taking hold, but there are also many other effects of having undesirable bacterial species in the gut. These include chronic inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis, and an increased risk of conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. There has also been some suggestion that the microbiota contributes to some psychological disorders.

Discussing the latest study, co-lead author Jonas Schluter of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center – who has carried out previous work on the 'stickiness' of bacteria – said: 'Our gut is lined with our own epithelial cells, and we use these to secrete all kinds of compounds into the gut. That is, we don't just absorb nutrients from our gut, we release a lot of things back in. This includes mucus, which can be modified so that it sticks to particular bacteria and also antibodies – one of the key tools of the immune system.

'In particular, a class of antibody called IgA (immunoglobulin A) is released into the gut in large quantities. This is a sticky molecule that comes in a vast number of forms where each one can preferentially target a particular strain or species of bacteria. By using things like mucus and IgA, therefore, humans have the ability to make certain bacteria sticky. We are proposing that this can be used to hold them close to the epithelial surface in the gut.'

Senior author Professor Kevin Foster of Oxford University added: 'Our study is based on a computational model of the gut and the key next step is a direct empirical test of our idea. However, as we discuss in our study, existing data do support our idea that stickiness may be a simple and powerful way to control the bacteria that we carry with us.'

In a guest post, Martin Conway, professor of Contemporary European History at University of Oxford, explains the underlying issues behind this week's attacks in Brussels.

'What we feared has happened,' remarked Charles Michel, the prime minister of Belgium, in the immediate aftermath of the horrible and violent attacks on Brussels airport and the Maelbeek metro station on March 22.

Yes, indeed. Nothing is less surprising than that the vortex of terrorism and repression that has developed since the November 2015 attacks in Paris should have resulted in these new violent attacks.

But that doesn't mean we shouldn’t consider how these circumstances came about. These events reflect several, much longer-term issues.

First of all, there is the ever more emphatic pursuit of a level of security that can never be achieved. European leaders from François Hollande to David Cameron are promising somehow to wipe away the threat of terrorism from Europe. That of course cannot happen.

Only those who believe most naively in the capacities of Europe’s current intelligence structures – hovering over the incessant noise of email, mobile phone messages and the twittersphere – will believe that what has come into existence can be willed to disappear.

There is indeed a police problem – one above all of capacity and coordination – but the solution to Europe’s security crisis can never simply be more security.

That has to be combined with more imaginative efforts to look at the origins of the problems. And that of course means that Europeans need to look at themselves and the societies they inhabit.

Brussels was not randomly selected for this attack. It is a prosperous, peaceful and predominantly secular city. In many ways it embodies the values that many in 21st-century Europe hold dear. But it is also home to radicalised minorities.

Most bars on most nights of the week within easy reach of the Maelbeek metro station will contain a cross-section of the successful young generations of Europe. They mix in those easily permeable domains between European institutions, lobbying and journalism.

But think also of those who are not present in those bars: the micro-communities of Europe’s margin. Some of those are well established and familiar; but others are emphatically more recent – notably the arrival in the poorer districts of central Brussels of populations from North Africa and the Middle East.

These are people with relatively little interest in the society they now inhabit. And indeed Belgium seems to have little to offer to them, beyond the immediate and insubstantial opportunities of transient employment. They are the expendable populations, and they know themselves to be that.

Which brings us inevitably to Molenbeek. That one commune of the 19 which constitute the city of Brussels should have come to symbolise all its problems is in many respects unfair.

What has happened in Molenbeek could easily have happened in the neighbouring communes of Anderlecht or Schaerbeek. But the wider reality is indisputable – inner-city communities often lack clear structures of governance, social solidarity and opportunity.

There is a Belgian and a European explanation for that. The Belgian dimension must focus on the manifold complexities of the Belgian state.

It is inefficient and simply lacks the capacity to provide effective governance to many of the most disadvantaged populations who now live on its territory.

Belgium is not, by contemporary European standards, a conventional state. It lacks an instinctive ethos of centralism. Belgians know themselves to be diverse and are rightly proud of the fact that they do many things at a local, rather than national level.

That works when the participants sign up to rather basic values of co-existence, but it fails when they contain populations who do not experience the basic amenities and opportunities which draw people into the European social contract.

But it is that social contract which has been stretched to breaking point and beyond, in Belgium and elsewhere, over the past 20 years or more. The replacement of structures of social solidarity with the relentless logic of the market, have hollowed out the ways in which the poorer communities of Brussels and many other cities across Europe have invested in their larger collective existence.

There are of course many reasons for that, most obviously the way in which the scale and diversity of migration has transformed cities into communities where there is no identifiable majority.

But the larger picture, in Brussels and elsewhere, is the degree to which social inequality has generated its own dynamics of marginalisation and radicalisation.

In Molenbeek, as in many other disadvantaged communities, the emergence of cultures of militant Islam has been less a stand-alone phenomenon than the product of wider phenomena of poor schooling, limited economic opportunities and consequent petty criminality.

Previous manifestations of terrorism in Western Europe have had immediate and tangible origins. The conflicts between communities in Northern Ireland and between Basques and the Spanish state are two of the most well-known causes of the 20th Century.

It is tempting to see the current waves of terrorism as very different – the result of the sudden invasion of militant Islam. But in many respects the origins of the current violence remain just as local.

They lie in the willingness of young men of immigrant populations to turn the quasi-criminal expertise learned in their formerly marginal lives to more political and violent ends.

For some, such radicalisation leads to Syria and back. For others, there is no need to travel further than across the cities of Brussels and Paris from the neighbourhoods of the marginalised to the bars, music venues and metro stations of the comfortable classes.

All of which suggests that the problems that we – a pronoun which is more exclusive than we are often inclined to recognise – confront today are not going to go away soon.

The current terrorism is so amorphous and so shallow in its political affiliations that it may fade away, as those drawn towards it today are attracted to the more immediate opportunities of tomorrow.

But it is more likely that the breaking up, arrest and imprisonment of particular networks of individuals will simply be replaced by other such groups, who will similarly find in particular languages of Islam the vehicle for their angers and their emotional rejection of wider society.

Putting back together Europe's social contract might take longer than any of us would like to think.

Professor Conway's article appeared in The Conversation.

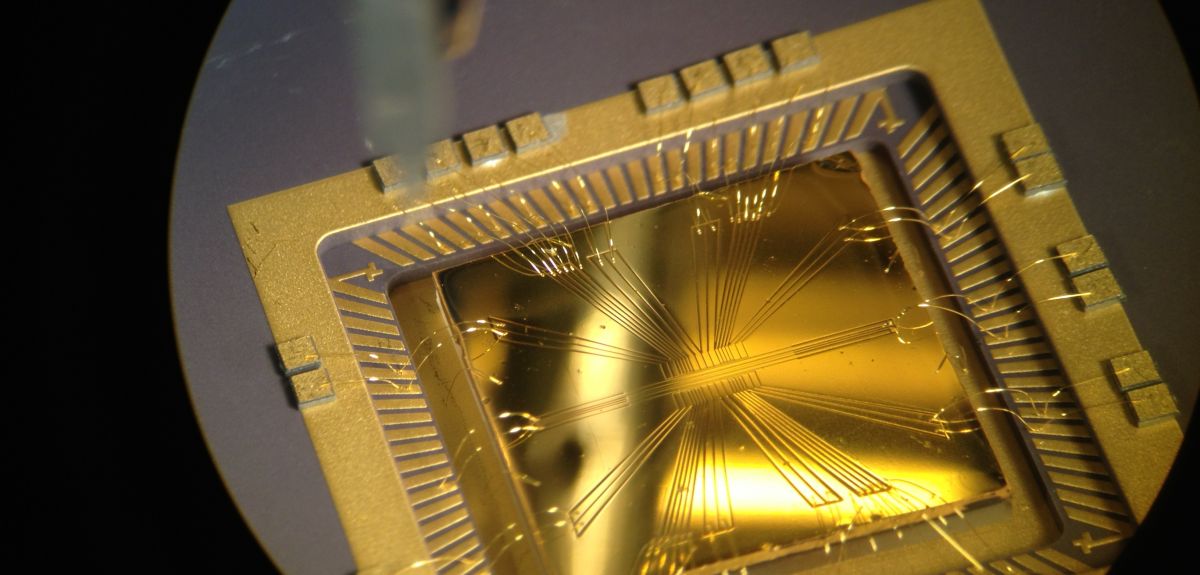

A stunning close-up image of a gold ion-trap chip has landed an Oxford DPhil student first place in the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council's (EPSRC) national science photography competition.

Diana Prado Lopes Aude Craik, a DPhil student working in the Ion Trap Quantum Computing Group in the Department of Physics, is the overall winner of this year's contest for her picture 'Microwave ion-trap chip for quantum computation'.

And Dr Dario Carugo, currently a visiting researcher at the Institute for Biomedical Engineering (IBME) in the Department of Engineering Science, was awarded second place in the innovation section of the competition for his image of fluid streams from an oscillating microbubble.

Diana, whose supervisors are Professor Andrew Steane and Professor David Lucas, and who worked on the project featured in the image with Norbert Linke, said: 'We work on designing, fabricating and testing prototype building blocks of an ion-trap quantum computer. Such a quantum computer would store information in single ions (charged atoms), which are used as "quantum bits" (qubits).

'We are very happy that the EPSRC photo competition has given us the opportunity to share our excitement about our work with a wide audience of science enthusiasts.'

Diana's picture caption states: 'When electric potentials are applied to this chip’s gold electrodes, single atomic ions can be trapped 100 microns above its surface. These ions are used as quantum bits ("qubits"), units which store and process information in a quantum computer. Two energy states of the ions act as the "0" and "1" states of these qubits. Slotted electrodes on the chip deliver microwave radiation to the ions, allowing us to manipulate the stored quantum information by exciting transitions between the 0 and 1 energy states. This device was micro-fabricated using photolithography, a technique similar to photographic film development. Gold wire-bonds connect the electrodes to pads around the device through which signals can be applied. This image is taken through a microscope in one of Oxford University's physics cleanrooms. The wire-bonding needle can be seen in the top-left corner. The Oxford team recently achieved the world’s highest-performing qubits and quantum logic operations.'

'Fluid streams from an oscillating microbubble'

'Fluid streams from an oscillating microbubble'Image credit: Dario Carugo

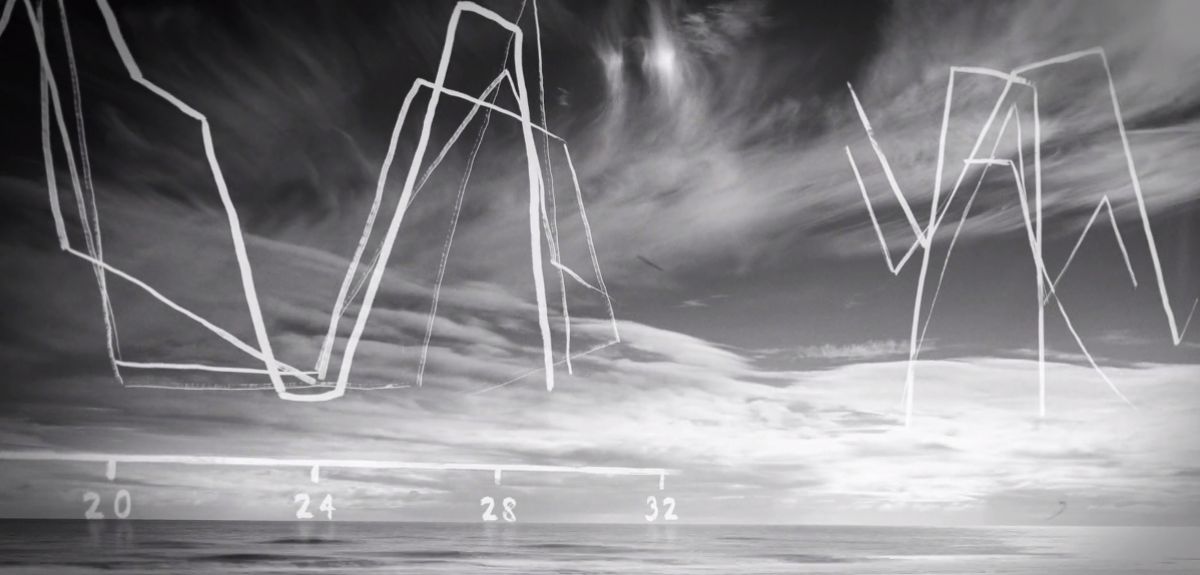

Dario's image was taken while completing his post-doc at IBME under Professor Eleanor Stride. His caption stated: 'The photograph shows fluid streamlines generated by a gas microbubble exposed to an ultrasound wave. Microbubbles are only few micrometres big, on the same scale as bacteria or the diameter of a human hair. They comprise of a gas core enclosed by a thin shell, and are frequently used in the clinic as contrast agents for echocardiography. In the presence of ultrasound, they oscillate by cyclically expanding and contracting. This causes the displacement of the surrounding fluid and the generation of a fluid flow, which takes the form of counter-rotating vortices. In this photograph, fluorescent microparticles are added to the fluid in order to visualise the flow streamlines using a microscope. Image contrast enhancement and colouring was performed using ImageJ. Importantly, the observed fluid flow could be exploited in therapeutic applications as a means of effectively transporting drugs towards desired locations within the body (ie cancer tissues).'

One of the judges was Professor Robert Winston, who said: 'It is crucial to promote greater understanding of science and engineering research, and the role it plays in making new discoveries, developing new technologies and in making the world a better place for us all. These are truly inspirational images and tell great stories. It was a real pleasure to take part as a judge and I hope people will want to find out more.'

Professor Philip Nelson, EPSRC's chief executive, said: 'Yet again, the standard of entries into this year's competition shows the inquisitive, artistic and perceptive nature of the people EPSRC supports. I'd like to thank everyone who entered; you made judging a very hard but enjoyable task.

'This competition helps us engage with academics and these stunning images are a great way to connect the general public with research they fund, and inspire everyone to take an interest in science and engineering.'

The competition received over 200 entries which were drawn from researchers in receipt of EPSRC funding.

'It became very hard to breathe…but I just had to remember to keep calm and still.'

You might be thinking that this sounds like a hapless victim from one of the increasingly ubiquitous Nordic noir dramas taking over our TV screens – so you may be surprised to learn that it's the experience of one of the subjects in a recent University of Oxford study! Olivia Faull and colleagues from the Oxford Centre for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain (based in the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences) devised an experiment to look at what is happening in the brain when we might be about to become breathless. And the results have striking ramifications that will help us better understand – and may eventually lead to new treatments for –asthma and other chronic respiratory disorders.

Asthma costs the NHS £1bn a year, and the economy a further £2bn, due to time off sick (Asthma UK). It has long been suspected that some cases of asthma may be made worse by stress and worry. Sometimes breathlessness is out of proportion with what is actually happening physiologically in the lungs. In some people anxiety or worry can even bring on an asthma attack. Researchers in Oxford became interested in what is happening where in the brain when this reaction occurs.

A normal functioning PAG is clearly a good thing. We need to know when we are in danger, whether from something we could run away from – such as a hungry lion – or something we can't escape but could endure, such as becoming breathless. But what happens when things go wrong?

Scientists have known for some time that a tiny part of the brain called the periaqueductal gray (or PAG for short) plays an important role in how we perceive threat. Animal studies have revealed this bundle of cells in the brainstem to be the interface between automatic processes – such as breathing and heartbeat – and consciousness. The PAG is a group of cells ('grey matter') less than 5mm in diameter. Historically it has been very difficult to study in humans because it is so small and buried so deep. But the Oxford team managed to isolate the PAG using state-of-the-art magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with super fine resolution.

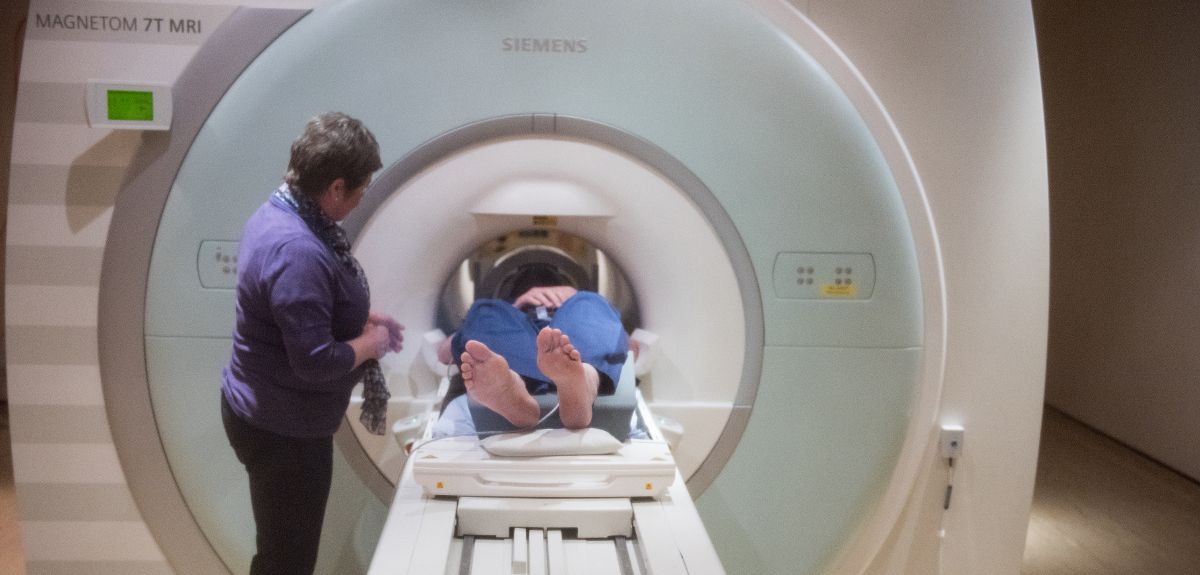

Olivia and colleagues scanned a group of healthy volunteers in the ultra high-field 7 Tesla MRI scanner. The volunteers wore a breathing system similar to a snorkel, that could be altered to produce a resistance when subjects breathed in (like breathing through a very narrow straw). During the scan, subjects looked at a screen that showed three different symbols at various times. Eventually the subjects learnt the meaning of the symbols – for instance the triangle meant that nothing would happen and they could breathe normally, and the star meant that their air would definitely be restricted and they would become breathless.

Volunteers therefore learned when they may be about to find it difficult to breathe. Olivia was then able to look at what was happening in the PAG both when people thought they might become breathless, as well as during the difficult breathing itself. Olivia wanted to know what was happening when people anticipate breathlessness, to better understand the stress and anxiety that exacerbate it. The study found that averaged over all participants, a particular subdivision of the PAG (called the ventrolateral column) became active when people anticipated that they might become breathless, and another subdivision (called the lateral column) became active while they were actually breathless. This means that different subdivisions of cells within the PAG are doing different things throughout the course of breathlessness.

A normal functioning PAG is clearly a good thing. We need to know when we are in danger, whether from something we could run away from – such as a hungry lion – or something we can't escape but could endure, such as becoming breathless. But what happens when things go wrong? It could be that in people who are hyper-sensitive to threats, the function of the PAG or its communications to the rest of the brain are altered. For example, some people with asthma may get very stressed if they can't find their inhaler, and this may even bring on an attack: perhaps the PAG is telling them that they are in danger of becoming breathless (even if, physiologically, at that moment they are breathing normally).

Now that this ground-breaking MRI experiment has enabled researchers to know where and how to look at the PAG, they can carry out further studies to find out more about asthma and other conditions where the physiology doesn’t match the perception – such as chronic pain or panic disorders. Such work could lead to the development of new treatments, to see whether they have any effect on this tiny, hitherto inaccessible part of the brain. These could be new medicines or new behavioural interventions such as as mindfulness or cognitive behavioural therapy, or combinations of both.

The full article is published in the journal eLife.

- ‹ previous

- 128 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?