Features

Scientists keen to understand and preserve global biodiversity have been quietly going about a mammoth task: indexing the world’s known species.

So far the Catalogue of Life has indexed over 1,368,009 species and the latest edition features a database from Jeya Kathirithamby of Oxford University’s Department of Zoology detailing Strepsiptera, a strange order of parasitic insect.

Strepsiptera are endoparasites – they live inside their host – with almost all females spending their entire lives inside the body of other insects and males emerging as free-living adults to mate before they die, just five or six hours later.

‘The females are totally endoparasitic for their entire life history (except in one family) and all that is visible of an adult female is an extruded cephalothorax,’ Jeya tells me. ‘The female is nothing more than a “bag of eggs”, having lost all structures such as eyes, antennae, mouthparts, legs, wings and external genitalia any other insect would possess.

‘This dramatic difference between male and female makes Strepsiptera interesting model organisms for studying such aspects as mating and reproduction.’

Jeya is a world authority on these parasites where males and females can have such different lives that they even choose entirely different hosts:

‘There is a family where the males parasitize ants and the females parasitize grasshoppers, crickets or mantids. Due to the extreme sexual dimorphism and dual hosts, the sexes could not be matched until recently. We have achieved this using molecular data.’

Surprisingly, although Strepsiptera can infect and live inside the host insect for almost its entire life, the host seems unaffected and can even have its lifespan extended.

‘Strepsiptera have adapted to the life cycle of whatever host they parasitize,’ Jeya explains. ‘The comparison of the strepsipteran life cycle to the life cycles of the various hosts they parasitize is fascinating: For example the strepsipteran life cycle in a host which is a eusocial wasp is different to that of a host which is a solitary wasp and is different to that of a host which is an ant.’

Despite its unusual lifestyle this order of insect is far more than a curiosity: there are thought to be more than 600 species, with genetics revealing that individuals that look identical are in fact different species.

A recent molecular study carried out by Jeya and her collaborators found that a monotypic species in the southern states of the USA, Mesoamerica and the Neotropics revealed as many as ten cryptic species – animals which appear identical but are genetically distinct.

‘The global Strepsiptera database in the Catalogue of Life has host records and geographical distribution. These will be linked to the database of the hosts and to GenBank data. In our molecular studies, we sequence the hosts as well in order to check for contamination,’ Jeya tells me.

‘Like most Strepsiptera we find in the field the hosts are also often new to science. Here again there will be links to molecular data of the hosts. Strepsiptera parasitize seven orders of Insecta so this will be a substantial contribution.’

According to Jeya, Strepsiptera could include so many examples of cryptic speciation because of the different hosts they parasitize or their geographical distribution.

She comments that understanding the factors involved could prove very helpful in the study of a wide range of insects:

‘For instance, we are working on the phylogeny of crickets from Central America because we collected a large sample of crickets while looking for strepsipterans. Many of these crickets are new to science and at present there is no comprehensive data for crickets of Central America.

‘Both the molecular data and the geographical distribution of the cricket hosts will be linked to the database. This information will be invaluable for future researchers. Similarly, we are working on another little known host group in another area.’

Dr Jeya Kathirithamby is based at Oxford University’s Department of Zoology.

Watching a dead animal rot may not sound like everyone’s idea of fun but for insect expert Sarah Beynon it can provide a feast of information.

Sarah, from Oxford University’s Department of Zoology, took part in Hippo: Nature's Wild Feast which airs tonight on Channel 4, 9pm. The programme reveals what happens to the carcass of a hippopotamus in the wild over a week, using high-tech equipment to track the vast array of predators, scavengers and insects that strip the body down to the bone.

‘The hippo is essentially a whole ecosystem to an insect,’ Sarah tells me. ‘During the decomposition process, it goes through five stages of decay; fresh, bloated, active decay, advanced decay, and remains. Each stage supports a unique suite of insects.

‘Also, the different parts of a hippo support different insects - the flesh, skin, bones and gut contents all have different species feeding on them. In fact, insects are the only creatures that will feed directly on the tough, dry skin.’

The hippo carcass studied by the team was located in Zambia's Luangwa Valley. Sarah explains that in Africa such a body may support more than 300 species of insect, with millions of individual insects calling the carcass home.

Sarah was one of the scientific team studying the carcass, her work included observing insect behaviour, collecting specimens, and then commenting on each day’s footage for the programme.

‘My personal highlights were getting up close and personal to the hippo carcass,’ she reveals. ‘I had to don a fully protective plastic boiler suit and mask to guard against potential disease, and being out in 46˚C heat (ground temperature 64˚C), it was rather warm to say the least, but well worth it to see the wealth of insect life up close and personal.

‘The metallic green hide beetles were feasting on the parched skin, whilst a host of hister beetles were preying on all other insects feeding on the carcass.’

But with such a massive meal on offer she had to be on the lookout for some of the larger diners: ‘We got stranded at night on the river bed right next to the hippo carcass surrounded by well over 200 crocodiles and 7 hyenas!

‘We got the vehicle stuck in the sand and had to dig it out in torchlight with the hyenas and crocs waiting for us to leave so they could resume their feast. Seeing so many pairs of eyes glowing in torchlight was an awe-inspiring experience.

‘In fact, every time I went filming insects, we always seemed to run into the large game at very close proximity - a herd of elephants when setting the light trap, and hyenas when searching through dung for dung beetles! Quick retreats were called for in all cases!’

Whilst the cameras recorded animals visiting the hippo day and night Sarah and the team found innovative ways to study the insects – using radio transmitters mounted on individual insects to track their movements. She believes this technology has great potential, particularly in investigating the large-scale impacts of pesticides on insect populations.

The filming may be over but Sarah is flying back with plenty of new data and specimens that could still spring some surprises: ‘All specimens taken will be identified, with the hope of finding species new to science. When I was in Zambia last year, I found a sub-species new to science, so it is very possible, as the country is so under-studied.’

Hippo: Nature's Wild Feast airs Monday 7 November 2011 on Channel 4, 9pm.

Citizen science at Oxford

Citizen science at OxfordAll publicity is good publicity, or so the saying goes, and so by all accounts I should have been pleased by the mention of our Galaxy Zoo project in the Times Higher Education a couple of weeks ago.

On closer inspection, though, there’s something really rather odd about the argument it presents, and not just in giving Galaxy Zoo, which was developed and led here at Oxford University, as an example of an American project (to be fair to THE, they printed a letter correcting this misconception in today’s edition).

The THE article divides into two sets of examples. Two examples from the past (the mathematician Ramanujan, and the discovery of fossils by Mary Anning) and one contemporary story illustrate the remarkable contribution that can be made by exceptional individuals from outside the academy. Inspirational stuff, for sure, even if, as in the case of Ramanujan and Sharon Terry, the chaplain turned biologist mentioned in the article, they were swiftly embraced by conventional institutions.

These shining, trail-blazing examples are contrasted with modern citizen science, such as Galaxy Zoo or Cornell’s amateur birdwatching projects. These, we’re told, are ‘passive’, involving only rudimentary observational activities, instead of a ‘more active and in depth approach’. I’ve dealt with similar criticism of the projects, but there’s a more interesting point here in working out how to encourage deeper engagement with modern scientific data.

The article calls for more openness, leaving the impression that us academics are keeping the data and the fruits of our labours to ourselves.

This isn’t the place to jump into the arguments for open access to journals, but in my opinion what’s missing isn’t a lack of access, but often a lack of confidence. We’ve seen with Galaxy Zoo that there is a tremendous desire to help the process of understanding the Universe - the motivation most often given by respondents to our surveys - but that doesn’t translate to a desire to be dropped head first into a sea of data, literature and jargon.

If you’re a mathematician of the calibre of Ramanujan, such a sink or swim approach will work fine, but for the rest of us some confidence building is needed. What citizen science can do is to build a series of experiences, each richer and more complicated than the last, each of which constitutes an authentic contribution to science.

As Galaxy Zoo volunteers move from classifying objects, to discussing unusual finds on our forums, to collaborating with each other and with the professional scientists on projects, they are essentially navigating an alternative to the traditional career structure. Instead of taking multiple degrees before contributing to research, they are doing something useful from the start, and as a result many more have the confidence and ability to strike out on their own.

The remarkable contribution of Galaxy Zoo volunteers has been made possible by this infrastructure. After all, the project uses almost entirely public data but significant amateur discoveries have only come through our interface, and our supportive and collaborative community.

We’re putting a lot of effort into building tools that gradually lead into this sort of free research. We have just released a paper that depends substantially on the collaboration between professionals and volunteers on the Galaxy Zoo forum. Hubble Space Telescope observations are scheduled this month to follow up on objects identified by volunteers through careful and targeted work.

Does that sound like ‘passive’ participation to you? Me neither.

Dr Chris Lintott, Principal Investigator of Galaxy Zoo, is based at Oxford University's Department of Physics.

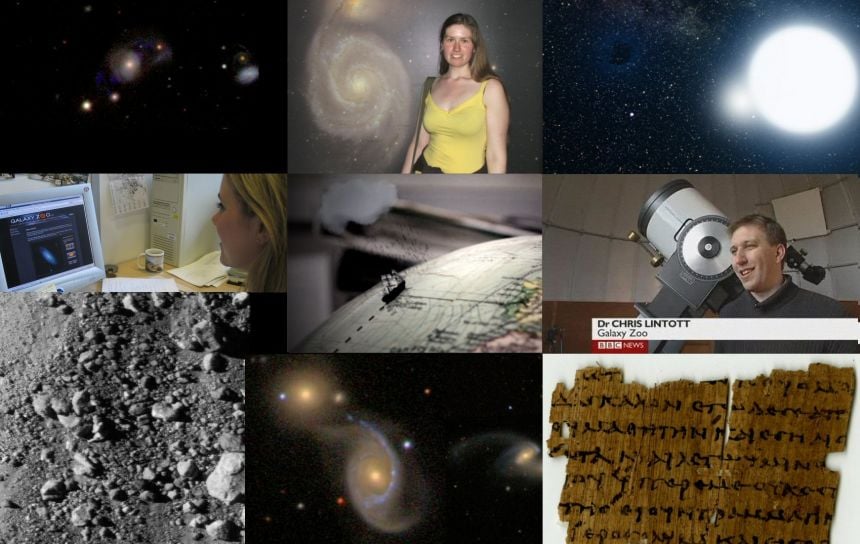

Image: highlights from Oxford-led citizen science projects [L-R] distorted galaxies from the new Galaxy Zoo paper; Hanny van Arkel, a schoolteacher who used GZ to find a new type of astronomical object; an eclipsing binary system was discovered by volunteer Carolyn Bol using planethunters.org; launch of GZ website; oldweather.org mines ship weather data; BBC Breakfast and Today interview Chris and GZ volunteers; Moon Zoo volunteers study the lunar surface; GZ Mergers searches for merging galaxies; Ancient Lives gets the public to help transcribe papyri.

Genetically modified male mosquitoes have been shown, for the first time, to mate successfully in the wild.

The experiment, carried out in the Cayman Islands and reported in Nature Biotechnology, shows that males, modified so that any offspring they father die before reproducing, could help to tackle outbreaks of dengue fever and other insect-borne diseases.

‘We were really surprised how well they did,’ Luke Alphey, a visiting professor at Oxford University and chief scientific officer of Oxford University spinout Oxitec, which developed the approach, told BBC News Online’s Jonathan Black.

‘For this method, you just need to get a reasonable proportion of the females to mate with GM males - you'll never get the males as competitive as the wild ones, but they don't have to be, they just have to be reasonably good.’

The GM modified male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes made up 16% of the male population of the trial area and fathered 10% of larvae – close to the mating success rate of wild males and evidence the technique could work outside the lab.

Aedes aegypti is a target because it carries dengue fever – afflicting an estimated 100 million people each year with some countries seeing ‘explosive’ outbreaks.

Luke explains that bednets offer no protection against dengue because the female mosquitoes carrying the virus bite during daytime.

‘We don't advocate [GM mosquitoes] as a 'magic bullet' that will solve all dengue in one go,’ he adds, ‘so the question is how it fits in as part of an integrated programme - and for dengue, it would be a huge component of an integrated programme.’

The next stage is to see if the release of a group of GM males can have a significant impact on the number of cases of dengue.

Luke Alphey is a visiting professor at Oxford University’s Department of Zoology.

Oxford University helped to fund the development of the approach through four awards from the Oxford University Challenge Seed Fund (UCSF). Oxitec was spun out of Oxford University by Isis Innovation in 2002.

Many of them are in Earth’s neighbourhood, patrolling the space between Mars and Jupiter, but there’s a lot we don’t know about asteroids.

Now new observations from the VIRTIS instrument aboard the Rosetta spacecraft are revealing what the potato-shaped asteroid Lutetia is made of.

I asked Fred Taylor of Oxford University’s Department of Physics, one of the team reporting the new findings in this week’s Science, what makes Lutetia special and what this new research tells us about our rocky neighbours…

OxSciBlog: Why is Lutetia an interesting asteroid to study?

Fred Taylor: All of the asteroids are interesting, because there is such a variety of sizes, shapes, and compositions. If we want to understand them we must study a large selection, and so far we only have close-up data on a few.

Lutetia is particularly interesting because it is one of the largest, about 130 km along its longest axis (it is potato-shaped) and a thousand trillion tonnes in mass, discovered as long ago as 1852.

Before the Rosetta encounter, Lutetia was remarkable for having an infrared spectrum (the way in which it reflects sunlight and emits heat radiation at different wavelengths) that is different from most other asteroids. We wanted to find out why this is, using the VIRTIS spectrometer.

OSB: What do the latest VIRTIS observations tell us?

FT: The composition of the surface of Lutetia turns out to be nearly the same everywhere, whereas most asteroids and meteorites have a variety of materials exposed in different places.

The reason, it turns out, is that Lutetia is covered all over with a thick layer of dry, dusty soil that covers the hard surface. We know there is a hard surface, although we can't see it, because the density of Lutetia is very high, so most of it has to be hard rock with a significant metal - we'd expect mostly iron, but also nickel etc - content.

There's no sign of hydrated minerals or organic material, both of which are often present in other asteroids and meteorites. This, and the thick ubiquitous regolith, is what makes the spectrum of Lutetia unusual. The closest match we have found is to the so-called E-type meteorites, which are very depleted in oxygen (so the iron is present as sulphides etc rather than the more common oxides, for example), but we may not be able to confirm this without samples from Lutetia.

OSB: How do these results help us understand other asteroids/the asteroid belt?

FT: This was the largest asteroid yet studied close up, until the Dawn spacecraft arrived at Vesta recently (and will go on to the largest, Ceres). The big asteroids (larger than 100 km in diameter) are thought to be remnants of the primordial asteroidal distribution - this means they are not by-products of fragmentation events, and their physical properties were probably determined during the accretion epoch.

They may be the only large bodies we have studied that are relatively unmodified since the early days of solar system formation (but there are others, icy rather than rocky, in the Kuiper belt out beyond Neptune that we will visit some day).

OSB: What important questions about Lutetia remain to be answered?

FT: The next logical step would be to land on the asteroid and drill into its interior to find out what minerals are actually present, in what properties, and how they are distributed throughout the body, especially with depth, so we can see how Lutetia was originally put together. This of course is a major undertaking that will be some time in coming!

Professor Fred Taylor is based at Oxford University's Department of Physics.

- ‹ previous

- 194 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria