Features

Biologist Doctor Adam Hargreaves studies genetic alterations, how they give rise to novel phenotypes, and how these relate to evolutionary adaptation. His initial studies were of venomous reptiles, which led him to debunk a commonly accepted hypothesis. At a recent debate in Oxford members of the public and members of the International Society of Toxinology sided with Adam’s views on the evolution of reptile venom. Here, he explains the competing stories about how snakes and lizards got their toxins.

How biological novelties evolve, especially when thought to have played a major role in the subsequent success of a group, are of great interest to biologists. Of course, ideas of how these novelties might arise begin as a hypothesis, which can change quite dynamically over time. This has certainly been the case with reptile venom evolution.

Historically, venom was thought to have evolved twice within reptiles; once in venomous snakes (such as cobras) and again in venomous lizards (such as the Gila monster). However, in 2006 a publication in the journal Nature proposed that venom evolved only a single time in reptiles, based predominantly on the shared expression of genes known to encode venom toxins in venomous snakes in the oral glands of snakes and lizards traditionally considered to be non-venomous. It was therefore concluded that the majority of reptiles descended from a common venomous ancestor and, as a result, a new clade was named the Toxicofera (comprising all snakes and a number of lizards), implying the presence of venom in these groups. Consequently, many lizard species previously considered to be non-venomous were designated as venomous, including the Komodo dragon.

Over the past 10 years or so this hypothesis of a single origin of venom in reptiles (the 'Toxicofera hypothesis') has become considered to be established fact, and has been cited in both scientific and popular media (including on several UK television shows, such as QI). However, a large-scale and long overdue test of this hypothesis conducted during my PhD working with colleagues at Bangor University, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the Institute of Biological, Environmental and Rural Sciences at Aberystwyth University used cutting-edge DNA sequencing technologies to show that this hypothesis was unsupported. Furthermore, a comprehensive review of the evidence previously used to support the Toxicofera hypothesis suggested that it may never have actually been supported.

The study (published in the journal Toxicon) found that genes which had previously been proposed to encode venom toxins were in fact expressed in different body tissues at low levels. There was no evidence for a venom/oral gland-specific splice variant (an alternative product of the same gene which encodes a different protein) or a consistently increased expression of a toxin gene in the oral glands (where toxicity might be dependent on the increased dosage of a particular toxin). With this in mind, it appears that many genes which have been used to support the Toxicofera hypothesis are more likely be 'housekeeping' or maintenance genes, which encode normal non-toxic physiological proteins.

What is it doing expressing these toxin genes in its oral glands? Unless of course, the genes don't actually encode toxins.

In short, many of these genes code for proteins which are not toxins at all, but fulfil other biological roles. Additionally, one species sampled turned out to be crucial. I think one of our key results was that many of the proposed toxin genes are expressed in the oral glands and other body tissues of the Leopard gecko. This species belongs to one of the most basal (oldest) groups of squamate reptiles which pre-date the proposed venomous ancestor. With that in mind, what is it doing expressing these toxin genes in its oral glands? Unless of course, the genes don't actually encode toxins.

These findings have real-world applications for the development of improved treatments for snake bite, as Doctor John Mulley at Bangor University, senior author of the study, explained: 'Ruling out so many of the proposed toxins as actual components of venom means that snake venom is far simpler than was previously suggested, with the majority of venom complexity limited to just a few gene families. It seems likely therefore that we can develop more effective antivenom treatments which focus on combating the effects of just these families. More fundamentally, this new research demonstrates the power of advanced DNA sequencing technologies to shed new light on old questions, and to overturn established hypotheses regarding the evolution of venom in reptiles.'

A survey of gene expression in different tissues of the Burmese python, conducted by a different group of researchers based in the USA, also found that many proposed toxin genes are expressed in many different tissues outside of the oral glands, and at low levels. It appears that evidence to support the multiple evolutions of venom in reptiles is building, especially with the constant improvement and increasing use of DNA sequencing technologies.

As part of the International Society on Toxinology 18th world congress held in Oxford from the 25th to the 30th of September, a public engagement with science session was held for members of the public in the Sheldonian theatre. An Oxford-style public debate was held as part of this session with the motion This house believes that venom originated only once in the course of reptilian evolution. The motion was rejected by an almost unanimous vote, demonstrating widespread support from a large gathering of toxinologists that venom evolved multiple times in reptile evolution.

The differences between venom systems in lizards and snakes is very apparent, most notably how they use their venoms, with venom in snakes being used primarily as a way of immobilising prey items whereas venom in lizards is used as a defensive strategy.

This multiple origins hypothesis is of course the less parsimonious explanation, that is to say a trait evolving once is a simpler process than evolving several times. However, convergent evolution (where non-related species evolve the same trait independently) is widespread in nature, giving rise to analogous structures such as wings in bats and birds; both enable flight, but the evolutionary origins in these animals are different. The same can be said about the venoms and venom systems in venomous snakes and venomous lizards. Indeed, the differences between venom systems in lizards and snakes is very apparent, most notably how they use their venoms, with venom in snakes being used primarily as a way of immobilising prey items whereas venom in lizards is used as a defensive strategy.

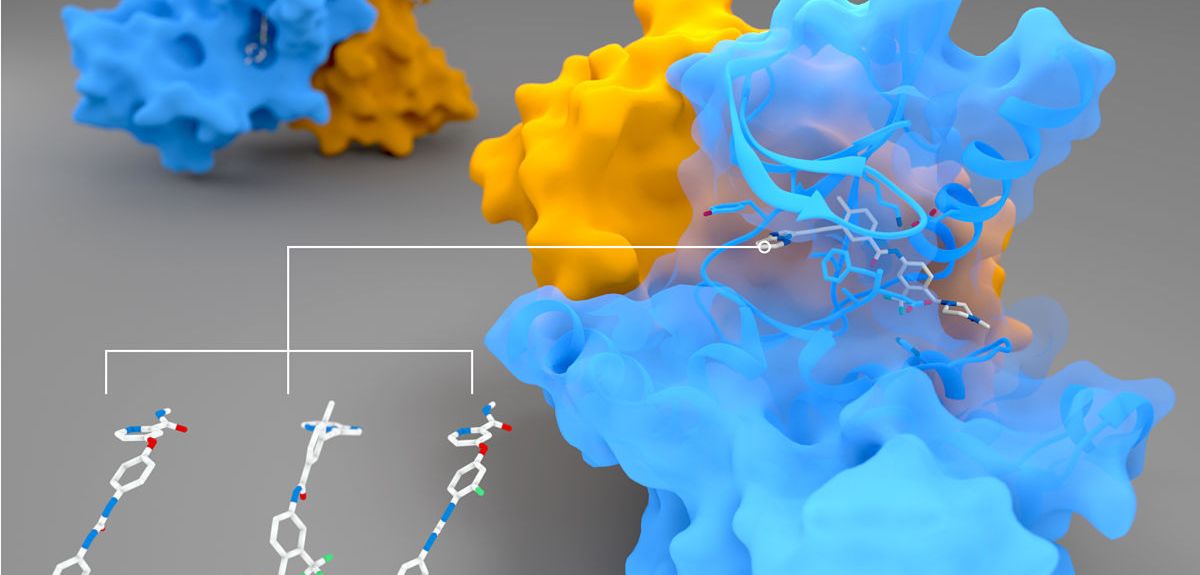

Ponatinib is an anti-cancer drug which has earned some notoriety for its cost (£90,000 per patient per year) and side-effects that were serious enough to temporarily suspend its use. But the findings from a recent Cell Chemistry and Biology paper led by the Structural Genomics Consortium suggest that this 'dirty' drug might actually hold the key for coming up with newer, more effective drugs for chronic illnesses such as Crohn's and Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

The Oxford Science Blog asked the first author, Dr Peter Canning (who worked on this study while at the Nuffield Department of Medicine) to explain what they found.

OxSciBlog: Why were you interested in ponatinib?

Peter Canning: Our main interest was originally in a protein called RIPK2 (pictured above), which has an important role in regulating the body's immune response. When the body is invaded by rogue bacteria, they can be detected by two human proteins, NOD1 and NOD2. But NOD1 and 2 need RIPK2 to pass on a signal that will activate an immune response to fight off the invasion.

This signalling can go wrong in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, and abnormal inflammatory signalling can even be a factor in some kinds of cancer. One potential cause of disease is if the NOD proteins start to signal constantly, even when there are no bacteria around. This then produces a constant signal from RIPK2, which in turn triggers a constant inflammatory response. If we can find ways of inhibiting this signal, we can stop it, and thus treat the disease. So RIPK2 is potentially a very interesting drug target for inflammatory diseases.

OSB: How do you go about finding inhibitors for a protein?

PC: We can use a number of methods, but one of the first screens we try at the Structural Genomics Consortium is to perform a 'thermal shift' experiment: we take the protein of interest, and we heat it.

Proteins are folded into a three dimensional shape, but when they get too hot, they unfold and lose their shape.

Proteins are folded into a three dimensional shape, but when they get too hot, they unfold and lose their shape. We exploit this change by using a dye that sticks to the unfolded protein core, and so it can only do so when the core is exposed. The dye is fluorescent, and you see these beautiful peaks in the fluorescent signal when the protein unfolds.

When we add a protein inhibitor into the mix, it has a stabilizing effect on the protein, so that it unfolds at a higher temperature. So you get an increase in the temperature at which you see a peak in the fluorescent signal.

OSB: So what happened when you added ponatinib to RIPK2 in this experiment?

PC: I’ve used this method to look for protein inhibitors many times, and the results with ponatinib were the most striking that I have ever seen. In my experience working on protein kinases like RIPK2, a good inhibitor might increase a protein’s unfolding temperature by about 10 ˚C.

However, with ponatinib, the melting point of RIPK2 increased by 23 ˚C. So that was immediately interesting.

OSB: Can you tell us a bit more about ponatinib, and how and why it was originally developed?

PC: Ponatinib is based on a drug called imatinib, which I've worked on before. Imatinib inhibits the BCR-ABL protein that causes chronic myelogenous leukaemia (a cancer of white blood cells) and gastrointestinal stromal tumours.

Imatinib was an amazing breakthrough that featured on the cover of Time magazine. It's a striking example of what is called target-based drug design

Imatinib was an amazing breakthrough that featured on the cover of Time magazine. It's a striking example of what is called target-based drug design: some clever scientists worked out that the specific fusion of two genes was producing the BCR-ABL fusion protein, and that this fusion protein was then resulting in the development of specific kinds of cancer. So they reasoned that targeting this specific protein would be a great treatment for this kind of cancer. And they turned out to be 100% right!

The problem is that to stop the cancer from coming back, you have to keep taking imatinib for the rest of your life. More or less inevitably, the disease-causing BCR-ABL eventually mutates, developing resistance to imatinib. So imatinib derivatives have now been designed to treat particular kinds of cancer when imatinib has stopped working.

One of these derivatives is ponatinib, which is designed to treat a very specific mutation of BCR-ABL. Its approval was actually retracted for a while, because it causes an increase in blood clots, leading to a greater risk of heart attacks and strokes in the patients taking it. It was then reapproved, but with restrictions on dosage levels and the conditions it can be used for: it’s really only for a subset of late-stage cancers.

OSB: How did you use ponatinib in your experiments?

PC: We wanted to solve the 3D structure of the RIPK2 protein to understand more about how it works as well as how drug molecules might bind. This involves using X-ray crystallography to determine the exact 3D arrangement of the atoms that make up the RIPK2 protein.

This is often a difficult challenge, as we first need to induce the protein to form into solid crystals. RIPK2 is a protein kinase, and it can be tricky to induce kinases to form crystals, due to their flexibility. However, if you add an inhibitor so that the protein locks into a particular 3D shape, it can make the protein a lot easier to crystallize.

Once we have grown a protein crystal, we take it to the Diamond Light Source facility, which produces incredibly powerful and fine beams of X-rays. We shine these powerful X-ray beams onto the protein, and that gives us a diffraction pattern of X-rays as they go through the crystal. Then we use computational methods to turn the diffraction pattern back into the structure of the thing that scattered the X-ray in the first place: this kind of X-ray crystallography was used to decode the structure of DNA as well. RIPK2 crystals were particular thin and small, and we were really only able to get our data because the X-rays at the Diamond Light Source are so incredibly focused.

But having ponatinib is what allowed us to stabilise RIPK2 enough for it to crystallize in the first place.

OSB: Why is it important to understand the structure of RIPK2, or any other protein?

PC: Understanding RIPK2's crystal structure not only helps us understand how protein kinases work, but structural information is incredibly useful if you're looking for a drug target. If, for example, we know that an inhibitor locks onto RIPK2 but also several other proteins, we can look for clues in the structure of the proteins to come up with a more specific inhibitor that will affect RIPK2 only, but not others: that is how you make good drugs that have low side-effects.

Understanding RIPK2's crystal structure not only helps us understand how protein kinases work, but structural information is incredibly useful if you're looking for a drug target

OSB: What other experiments did you do?

PC: We tried putting ponatinib on isolated human cells to see if it could block their inflammatory response by inhibiting RIPK2. And it turned out that it could.

We also looked at whether other similar drugs might also bind to RIPK2. As we hoped, we found three others that seemed to bind equally well. But when we put these drugs onto cells, we were surprised that only two produced the same potent effect as ponatinib. We don't fully know why that would happen.

One clue was that all the drugs (including ponatinib) that were very effective in cells were so-called 'type II kinase inhibitors': they work by binding to kinases and twisting them out of shape, thus blocking their function. The drug that didn't work as well was a 'type I' inhibitor: it simply blocks up the place where a key molecule (ATP) binds, and this may explain the difference. But we don't know for sure – it's a curious puzzle that we are still investigating!

OSB: Are these drugs potential treatments for inflammatory diseases then?

PC: The most marked effect in our experiments was from ponatinib, but it’s pretty unlikely that ponatinib would make for a good treatment. Its side-effects are too severe: inflammatory diseases like inflammatory bowel disease and Crohn's disease are chronic conditions. You’d need to take any treatment for a long time, and so you can't really risk something like increased heart attacks!

But thanks to ponatinib, we know the 3D structure of RIPK2, including its drug binding 'pocket', and this has provided us with some clues for how we might make modified drug molecules so that they target RIPK2 more selectively. With luck, such molecules could potentially provide a treatment for chronic inflammatory diseases in future.

How can lawyers draw on literature to make their case? Can English professors benefit from a legal perspective? These are among the questions to be tackled by a new network set up by TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities.

Dr Tessa Roynon of the Faculty of English Language and Literature and the Rothermere American Institute at Oxford has set up the ‘Fiction and Human Rights’ network, in collaboration with Natasha Simonsen of the Law Faculty.

To mark the launch, a one-day symposium is being held at the St Cross Building in Oxford on Saturday 7 November from 10.30am to 5.30pm.

It is called 'Dignity and the Novel since 1948' and will involve lawyers, literary scholars, philosophers and political theorists discussing the relationship between the modern novel and the concept of 'dignity' in legal theory and practice.

Dr Roynon says: 'Although the two faculties share a building, English and Law have not collaborated in this way before. The network will hold discussions and talks over the course of the next year and we hope that postgraduate students and academics from English and Law will come together to share ideas about fiction and human rights, and perhaps to form promising research partnerships in the future.’

Dr Roynon explains that literature and law have often approached human rights in different ways and believes the two can complement each other.

'I think the relationship between human rights law and world literature is conflicted,' she explains. 'In one sense it is affirming, vindicating and validating for novelists and literature academics to feel that literature makes a real, concrete intervention. For example in writing 'Half of a Yellow Sun', Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie informs otherwise ignorant people about the Biafran war and the Igbo cause. The very fact that PEN exists or that Amnesty has literature programmes endorses the usefulness and validity of literature.

She adds: 'On the other hand, while lawyers may well be sceptical about the ‘usefulness’ of literature, literature academics also take a sceptical view of the apparent specificity and confidence of human rights legal discourse. A work of fiction, such as Ralph Ellison's 1955 novel ‘Invisible Man’, might implicitly take apart, parody or show up the loopholes in the confident rhetoric of a document such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

'In the Declaration's Preamble, it says with great certainty, "Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world ..."

'This is not dissimilar to the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 in which wishful thinking is expressed as indisputable truth. As literary scholar Joseph Slaughter has asked, 'Is dignity 'inherent'?' Are rights 'inalienable'? Literature has space and time to explore the pitfalls of such a belief system and to question the power of language. A common process in a typical 'world novel' is that it will take apart one way of thinking and offer an alternative world view in its place.'

The symposium’s aim is 'to bring together an eclectic range of thinkers to analyse the ways in which the genre of fiction might or might not contribute to debates about the nature and role of dignity in human rights'.

Visiting keynote speakers include Stephen Clingman from the University of Massachussetts, Amherst, Zoe Norridge from Kings College London; and Philippe Sands QC.

Oxford-based participants include Ankhi Mukherjee, Michelle Kelly, Marina MacKay and Kate McLoughlin from the Faculty of English Language and Literature; Cathryn Costello, Jonathan Herring and Charles Foster from the Law Faculty; Dana Mills from the Department of Politics and International Relations, and Kei Hiruta and Carissa Véliz from the Faculty of Philosophy.

There will also be contributions from Helena Kennedy QC, Principal of Mansfield College, and Mark Damazer, Master of St Peter's College.

The event is open to the general public as well as members of the university. Advanced booking is essential. Visit the TORCH website for registration and the full programme.

This year is the 100-year anniversary of the death of Henry ‘Harry’ Moseley, a promising English physicist who died in Gallipoli in World War One in 1915, aged only 27.

His work on the X-ray spectra of the elements provided a new foundation for the Periodic Table and contributed to the development of the nuclear model of the atom.

He had been tipped for one of the 1916 Nobel Prizes and when he died, newspapers on all sides of the conflict denounced his death. One English newspaper declared he was “too valuable to die”.

To mark this anniversary, TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities and the Museum of the History of Science have co-organised a discussion on this question tomorrow evening (13 October).

Taking part in the discussion will be Silke Ackermann, director of the Museum of the History of Science; Liz Bruton, co-curator of the ‘Dear Harry’ exhibition into Henry Moseley’s life, and Nigel Biggar, Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford.

Professor Biggar has given Arts Blog a preview of his argument.

'In one sense, scientists are not special: surely every individual is too valuable to die. More exactly, unless we think along pacifist lines, scientists along with everyone else might have a moral duty to risk their lives in war for a just cause.

'Indeed some scientists might prefer not to be privileged with a special, safer status: for example, the future socialist economic historian, R. H. Tawney, deliberately chose to fight in the ranks as a non-commissioned officer.

'What's more, scientists ought not to pretend that somehow their academic calling exempts them - like medieval clergy or religious Jews - from the demands of political duty that fall on every citizen.

'If we think that Britain's fighting at all in WWI was just a dreadful mistake, then Moseley's death (like every other death) at Gallipoli was a tragic waste; but I suggest that Britain's belligerence as a whole was not a mistake, even if parts of it (like Gallipoli) were.

'All that said, however, there are of course very good pragmatic reasons why a country at war should exempt certain classes of citizen from front-line service--whether to play alternative important roles in the war effort, or whether to preserve cultural stock for the peace: maybe Henry Moseley should have been one of them.'

Tickets for the event are free, and can be booked online here. This is part of the programme of events for the centenary exhibition, 'Dear Harry...' - Henry Moseley: A Scientist Lost to War, staged by the Museum of the History of Science with support from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) which has been now been extended until 31 January 2016 due to popular demand.

If you aren't a sports fan, the language of sport might seem inescapable.

Either the ball’s in your court and you’ve got into the full swing, or else you’re about to throw in the towel and have to hope you’ll be saved by the bell. Sports jargon and idioms permeate the way we use English.

Professor Simon Horobin, of the Faculty of English Language and Literature at Oxford University, reveals that the language of sport comes to us from a huge variety of sources. For instance, the rugby terms “ruck”, “maul” and “scrum” come to us, respectively, from a Scandinavian word for “haystack”, a Latin word for “hammer”, and as a modified version of the military term “skirmish”.

The diverse origins of sporting terms reflect the wide range of languages which have influenced English vocabulary. ‘Sporting lexicons are like the English language in miniature,’ said Professor Horobin.

Some sporting terms reflect their international context. Cricket is popular round the world, particularly in Commonwealth countries, and the terminology has developed accordingly. The “doosra”, for instance, is a bowling technique which takes its name from the Hindi word meaning “other (one)”.

Perhaps more unexpectedly, the word “tennis” itself is said to derive from medieval France, where the game first developed. Players shouted “tenez!” (“take that!”) as they hit the ball.

Even in English-speaking countries, the regional differences can be surprising. In Britain, the difference between “rugby” and “football” is obvious. But one was originally known as “Rugby football”, named after the public school where the sport was invented, while the other became known as “association football”, perhaps to resolve the ambiguity.

“Association football” gave rise to the term “soccer”, which is used in the USA to distinguish it from American football – which itself developed from rugby.

Confusing. But one of the things Professor Horobin is particularly interested in is how slang and language conventions in sport separate “true fans” from the uninitiated: 'In British usage, you only need to hear someone say the score in a football match is “zero-zero” to know they aren't a true fan, since it should be nil-nil, or love-all if it's tennis or squash.'

Those who don’t follow football but watch matches during a World Cup will know this only too well.

“Nil”, incidentally, derives from the Latin “nihil”, meaning “nothing”. “Love”, meanwhile, is said to derive from the French “l’oeuf”, meaning “egg” – the shape of the numeral zero.

'I'm also interested in the way sporting terms and phrases have infiltrated non-sporting contexts, said Professor Horobin. Cricket is a good example. Since it's associated with fair play, we talk about “playing with a straight bat” to mean “behaving honestly and decently”, and it's “just not cricket” to refer to any behaviour that flouts common standards of fairness.'

Professor Horobin has discussed sports etymology on the BBC World Service Sportshour programme in the last few weeks. He also blogs about word origins on Oxford University Press' Oxford Dictionaries site.

- ‹ previous

- 142 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?