Features

Based on the strong reactions that it provokes from people, it would be fair to say that mathematics has an image problem.

Maths is one of the few skillsets, unlike reading for example, that people are not embarrassed to admit they do not possess. Class room memories of daunting equations and fractions with no immediate resonance to the real world, scare people into declaring they are frankly, “rubbish at maths”.

In reality, mathematics underpins the world around us in more ways than we could ever imagine. Just by paying bills, measuring home improvements and making everyday decisions, people do maths, often without realising.

Our new Scienceblog series will tackle these preconceptions, highlighting the role that maths plays in shaping our understanding of science, nature and the world at large.

In the first of the series, Michael Bonsall, Professor of Mathematical Biology at the Oxford University Department of Zoology, discusses his research in population biology, and what it tells us about species evolution and why grandmothering is important to humans.

What is mathematical biology?

It is easy to get lost in the details and idiosyncrasies of biology. Understanding molecular structures and how systems work on a cellular level is important, but this alone will not tell us the whole science story. To achieve this we have to develop our insight and understanding more broadly, and use this to make predictions. Mathematics allows us to do this.

Just as we would develop an experiment to test a specific idea, we can use mathematical equations and models to help us delve into biological complexity. Mathematics has the unique power to give us insight in to the highly complex world of biology. By using mathematical formulas to ask questions, we can test our assumptions. The language and techniques of mathematics allow us to determine if any predictions will stand up to rigorous experimental or observational challenge. If they do not, then our prediction has not accurately captured the biology. Even in this instance there is still something to be learned. When an assumption is proven wrong it still improves our understanding, because we can rule that particular view out, and move on to testing another.

By using mathematical formulas to ask questions, we can test our assumptions. The language and techniques of mathematics allow us to determine if any predictions will stand up to rigorous experimental or observational challenge.

What science does this specialism enable – any studies that stand out, or that you are particularly proud of?

Developing a numerate approach to biology allows us to explore, what at face value, might be very different biologies. For instance, the dynamics of cells, the dynamics of diseases or the behaviour of animals. The specialism allows us to use a common framework to seek understanding. The studies that stand out in my mind are those where we can develop a mathematical approach to a problem, and then challenge it with rigorous, quality experiments and/or observation. This doesn’t have to happen in the same piece of work but working to achieve a greater understanding is critical to moving the science forward.

You recently published a paper: ‘Evolutionary stability and the rarity of grandmothering’, what was the reasoning behind it?

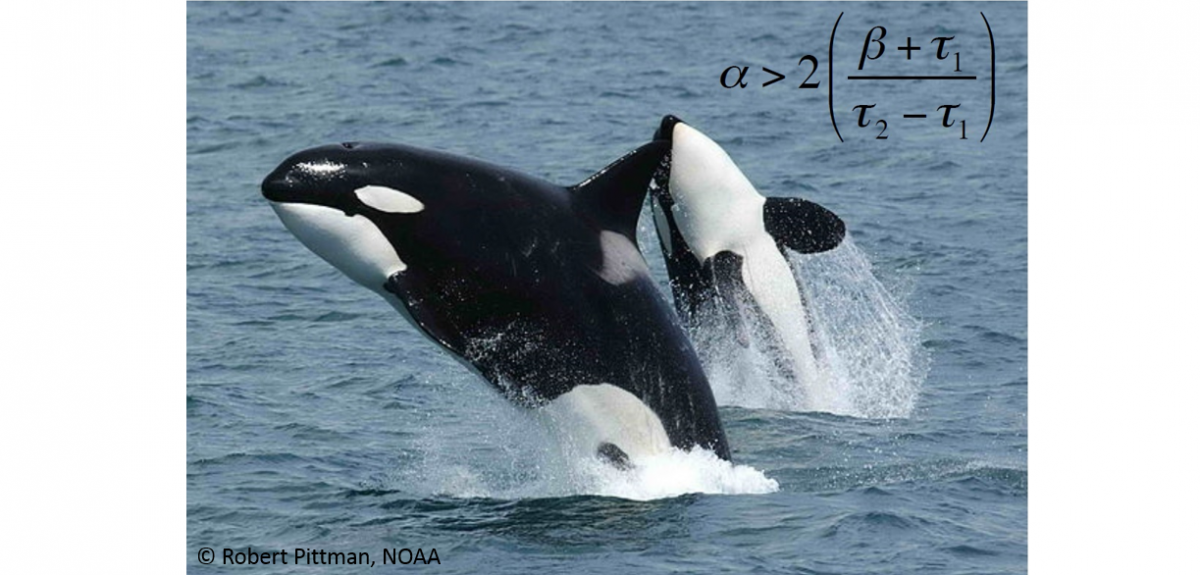

Grandmothering as a familial structure is very rare among animals. Whales, elephants and some primates are the few species, besides humans, to actually adopt it. In this particular study we took some very simple mathematical ideas and asked why this is the case.

Evolution predicts that for individuals to serve their purpose they should maximise their reproductive output, and have lots of offspring. For them to have a post-reproductive period, and to stop having babies, so that they can care for grandchildren for instance, there has to be a clearly identified benefit.

We developed a formula that asked why grandmothering is so rare in animals, testing its evolutionary benefits and disadvantages, compared to other familial systems, like parental care and co-operative breeding for instance, (When adults in a group team up to care for offspring). We compared the benefit of each strategy and assessed which gives the better outcomes.

What did the findings reveal about the rarity of grandmothering and why so few species live in this way?

Our maths revealed that a very narrow and specific range of conditions are needed to allow a grandmothering strategy to persist and be useful to animals. The evolutionary benefits of grandmothering depend on two things: the number of grandchildren that must be cared for, and the length of the post-reproductive period. If the post-reproductive period is less than the weaning period (the time it takes to rear infants) then grandmothers would die before infants are reared to independence.

We made the mathematical prediction that for grandmothering to be evolutionary feasible, with very short post-reproductive periods it is necessary to rear lots of grandchildren. But if this post-reproductive period is short, not many (or any) would survive. Species with shorter life spans, like fish, insects and meerkats for instance, simply don’t have the time to do it and focus on parental-care. Evolution has not given them the capability to grandparent, and their time is better spent breeding and having as many offspring as they can. By contrast long-lived animals like whales and elephants have the time to breed their own offspring, grandparent that offspring and even to great-grandparent the next generation.

We developed a formula that asked why grandmothering is so rare in animals, testing its evolutionary benefits and disadvantages, compared to other familial systems, like parental care and co-operative breeding for instance, (When adults in a group team up to care for offspring).

How do you plan to build on this work?

Although grandparenting isn’t a familial strategy that many species are able to adopt, it is in fact the strongest. Compared to parental-care and co-operative breeding, grandparenting has a stronger evolutionary benefit – as it ensures future reproductive success of offspring and grand-offspring – giving a stronger generational gene pool.

Moving forward we would like to test mathematical theories to work out if it is possible for species to evolve from one familial strategy to another and reap the benefits. Currently for the majority of species rearing grandchildren instead of having their own offspring is not a worthwhile trade-off.

What are the biggest challenges?

Ensuring that the mathematical sciences has relevance to biology. Biology is often thought to lack quantitative rigour. This would be wrong. The challenge is to show how the mathematical sciences can be relevant to, and help us to answer critical questions in biology. This will continue to be a challenge but will yield unique insights along the way in unravelling biology.

What do you like most about your field?

So many things. Firstly, the people. I work with a lot of very smart people, who I look forward to seeing each day. I also get to think about biology and look at it through a mathematical lens. Finally I think the specialism allows us to do fantastic science that has the potential to improve the world.

Is there any single mathematical biology problem that you would like to solve?

Developing a robust method to combine with biological processes that operate on different time scales - as this would have so many valuable, and to use one of my favourite words, neat, applications to our work.

Why did you decide to specialise in this area?

Because of the perspective that we can gain from it and because I love biology and maths. Unpicking the complexities of the natural world with maths and then challenging this maths with observations and experiments is super neat. And I can do (some of this) while eating ice-cream!

As the much anticipated Conservation Optimism Summit begins, Scienceblog talks to Professor EJ Milner-Gulland, Tasso Laventis Professor of Biodiversity in Oxford’s Department of Zoology. Co-creator of this landmark movement, she shares how she is working to protect some of wildlife’s most endangered species, what we can all do to be more environmentally conscious and why she has had enough of the doom and gloom around nature.

What was the inspiration behind the Conservation Optimism Summit?

The idea came about when I attended a lecture given by the great coral reef biologist Professor Nancy Knowlton, who founded the #OceanOptimism initiative. That campaign has done a fantastic job of highlighting positive stories about ocean conservation, and spreading them far and wide via social media.

Highlighting the challenges we face, rather than showing the progress that is being made to tackle them, makes people feel like there is nothing that they can do to help, when it really isn’t the case.

It got me thinking about how much we conservationists shoot ourselves in the foot by focusing on the negative. Highlighting the challenges we face, rather than showing the progress that is being made to tackle them, makes people feel like there is nothing that they can do to help, when it really isn’t the case. There is a lot to be proud of in conservation, and we need to be better at sharing it.

Once I had the idea in mind, I thought about how exciting it would be to have a Conservation Optimism event linked to the Earth Day events that people like Nancy Knowlton were also planning, and about the potentially powerful effect we could have in changing the conversation within conservation.

How does the format of the summit differ from other environmental campaigns?

Conservation Optimism is intended for everyone. Environmentalists, scientists, policy makers, academics, children – people in general. Our initiative encourages a global, collaborative way of thinking. While the only professional summit, specifically for conservationists, is taking place at Dulwich College, London, there are public events taking place all over the world. The flagship Earth Optimism event is organised by the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC, but there are also events in Cambridge and elsewhere, so it is possible for people to get involved anywhere. My hope is that everybody who comes along not only enjoys themselves but comes away with a renewed commitment to protecting the natural world and a set of actions that they can implement themselves to make a difference.

Image credit: EJ Milner-Gulland

Image credit: EJ Milner-GullandThe summit has been a culmination of months of planning and work, how do you plan to build on the initiative’s success in the future?

After the event we will sit down and analyse how people responded to the programme, did it inspire them or change their thinking or actions? Hopefully it will become an annual event, and more and more people around the world will get involved over time. The movement’s website will continue, and be updated with highlights from the summit and ideas to encourage people to stay connected with the Optimism movement.

What would you like the legacy of Conservation Optimism to be?

I hope conservationists will think hard about the way in which we approach our work, how we present it, and how we can be more forward-thinking and positive. We need to stop focusing on winning battles and collaborate to win the war. That begins and ends with the public working with us. We have to connect with them in a way that makes them feel that they can do something to change things.

Starting a community initiative, checking out local wildlife trust websites for news about public events, or simply replacing plastic bags with bags for life and plastic bottles for refillable ones, all helps. Plastic pollution is a huge threat to our oceans, with tragic consequences for wildlife. In all parts of the world, whether it's the UK or elsewhere, people can play a more active role in conserving their local wildlife. No matter where we live, every one of us can do more to protect the environment and get actively involved in conservation.

What’s next for you?

I’m going to Colombia in a couple of months to present at the International Congress on Conservation Biology and am looking forward to connecting with international colleagues and working how we can collaborate to tackle the challenges in our field.

What are the biggest challenges that you face in your work?

As scientists who are passionate about nature, it is challenging to make our work relevant to people's daily lives. Scientific language can be alienating; we need to bring nature to life in an exciting way that makes conservation interesting to people.

In today’s society everything we do as scientists has to have a real world impact to make it onto the agenda for governments and funders. People want to know ‘why should I care about this?’ and if we want to change the world for the better, we have to make a strong case that speaks to their needs and priorities.

Professor Milner-Gulland was inspired to start Conservation Optimism, after attending a lecture given by the coral reef biologist Professor Nancy Knowlton, who founded the #OceanOptimism initiative.

Image credit: Shutterstock

Professor Milner-Gulland was inspired to start Conservation Optimism, after attending a lecture given by the coral reef biologist Professor Nancy Knowlton, who founded the #OceanOptimism initiative.

Image credit: ShutterstockAnd the opportunities that you enjoy the most?

For me it is the feeling that you are making a difference, changing the way people think about the natural world. I enjoy working with young people from around the world who are really passionate about conservation.

Starting a community initiative, checking out local wildlife trust websites for news about public events, or simply replacing plastic bags with bags for life and plastic bottles for refillable ones, all helps. Plastic pollution is a huge threat to our oceans, with tragic consequences for wildlife.

What achievement are you most proud of?

My ecological research in Central Asia with the saiga antelope. I’ve stuck with it for more than 25 years, through a time when uncontrolled poaching catapulted the species towards the brink of extinction,to now, when saiga numbers are increasing, and there is hope again. My research has played a part in in getting us to this point, and although it has not been without its challenges, I am very proud to have been involved.

Aside from Conservation Optimism, what other projects are you working on at the moment?

One exciting new initiative is the Oxford Martin’s School Illegal Wildlife Trade programme. The illegal and unsustainable trade in wildlife is a major threat to global biodiversity. I am working to understand the drivers and motivations of wildlife consumers to work out how we can change this behaviour.

Do you think there are any unique challenges to being a woman in science?

Balancing family time with your passion for research is a constant challenge. Fortunately, universities actively try to support people to achieve this, much more so than in many other jobs. It is important for people to realise that it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. It is possible to do well in science and have a life outside of your work.

Are there any changes that can be made to make this balance easier?

A lot of the problem comes from young people being employed on short term contracts before they achieve permanent positions, and that makes it hard to plan your life. Once you have the security of a permanent position there are lots of positive initiatives in place to support people who have family commitments. But making that step is really hard. Research grants like the Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship which support people coming back into academia after a career break, are fantastic. These allow people to have research time to build their career when coming back, and make it easier to balance their various commitments.

How did you come to be a scientist?

I was raised in the British countryside, so grew up surrounded by nature and spent lots of time outdoors. I have always found biology fascinating, and was also fortunate to have a fantastic teacher who inspired me. Coming from a family who were keen to share their love and knowledge of nature with me was also an inspiration.

One piece of advice that you would give to other would be scientists entering the field?

Do what you love, rather than compromising on doing research that you feel you ought to do because it's fashionable or where the money is.

Professor Milner-Gulland pictured rowing, with her family

Professor Milner-Gulland pictured rowing, with her familyProf Armand D’Angour tells Arts Blog about the power, excitement, and drama of ancient Greek music

Thinking about ancient Greek poetry and drama, we tend to overlook a very important aspect. 'All the great poetry, from Homer through to the lyric age, and the great Greek tragedians – most of that was music,' says Professor Armand D'Angour. It was sung, played, and even danced.

Armand D’Angour is a Professor in Classical Languages and Literature (Faculty of Classics) at Jesus College. Formerly a professional cellist, he is currently engaged on a project to reconstruct ancient Greek music.

'I try to bring together all the different elements,' he says. 'My particular expertise is in ancient metre and rhythm. The rhythms are quite complicated and their names are quite off-putting, so my approach is to say "Let’s just hear what we’re talking about".'

Experts on ancient music theory have long understood the general principles of Greek melody. 'Ancient Greek has a natural melody - there was a pitch change on different syllables of words,' says Prof D'Angour. Ancient documents confirm that song melodies generally imitated the natural rising and falling pitch of words.

Prof D’Angour is working on scores and literary texts preserved on papyri and stone with musical notation above the words. 'When you have an ancient text, very often it’s got bits missing, but because we know the rhythms, we can conjecture what was in the gaps,' he explains. 'So also with the music.'

The ultimate goal is not an ‘accurate’ reconstruction, which is not only impossible but would misrepresent what ancient Greek music was like. 'Music was mostly orally transmitted. It wasn’t written down, it wasn’t recorded,' says Prof D'Angour. 'You cannot ‘recapture’ any single performance, and they were all different. Music was variable, but within the framework of an idiom.'

'What I'm trying to do is understand the musical idiom of ancient Greece – the general melodic and rhythmic principles of music. I want to say: Look, this isn’t the way it was sung, but this accords with the prevalent melodic idiom. If ancient Greeks heard it now, they would understand it to be their kind of music.'

It is not that an understanding of ancient Greek music and musical notation has ever really been lacking. Thanks to treatises like that of Alypius (5th century AD), following on the Elements of Harmony by Aristoxenus of Tarentum (4th century BC) and Harmonics by Ptolemy (2nd century AD), we know what the signs mean and how the modal systems worked. What Prof D’Angour is doing is trying to make coherent musical sense of what we have.

Now that there is music to play, Prof D’Angour’s reconstructions can be performed with a whole chorus and the two main instruments that were used in ancient Greece: lyre (or kithara) and double pipes (aulos). 'We don’t have any archaeological records of lyres, because they were made from wood and animal gut which perished,' he says.

But from ancient vase painting and descriptions in texts we can tell more or less what the size, shape, and look they would have had. 'We can then make them and play them.'

We tend to talk as if there was just one kind of Greek music, but in fact 'there were hundreds of different kinds of music'. And it was as ubiquitous as it is now: you could hear it in the home, in the temple, in the theatre. 'And of course ancient authors tell us what effect it had: it was moving, it sounded tragic, it was joyful or triumphant,' says Prof D'Angour.

Ancient Greek conservatives like the philosopher Plato thought that the kind of music you listened to affected your character. “Popular” music wasn’t beautiful, therefore it was bad. However, it could be effective, exciting, sublime. 'It wasn’t beautiful according to traditional canons of beauty.'

Looking at contemporary times, Prof D'Angour notes that 'the same aesthetic debate was going on: is beauty the criterion of goodness in art and music? Music is also about power, excitement, drama, which may be no less important.'

The discovery of a new species of pistol shrimp off the coast of Panama by a team of researchers including Dr Sammy De Grave of Oxford University’s Museum of Natural History was announced yesterday.

The news made headlines across the world – partly because of the shrimp’s bright pink claw, but also because Dr De Grave and his colleagues decided to name the shrimp Synalpheus pinkfloydi after the band Pink Floyd.

This gave journalists the chance to flex their headline-writing muscles. ‘Shrimp found on the Dark Side of the Lagoon,’ said the Oxford Times. Many went for the less imaginative ‘Shrimp Floyd’.

In trying to think of a headline for this article, Arts Blog came up with Brine On You Crazy Diamond, Goodbye Krill World, Fish You Were Here, Dark Side Of The Tuna and Another Shrimp In The Wall. All ended up in the bin.

Although this all seems like a lot of fun, naming the shrimp after Pink Floyd actually helped Dr De Grave and his team to get across the shrimp’s features: by closing its enlarged claw at rapid speed, the shrimp creates a high-pressure cavitation bubble.

When this bubble implodes, it creates one of the loudest sounds in the ocean, which is strong enough to stun or even kill a small fish.

That never happened to any of Pink Floyd’s fans who stood next to the amps during a gig.

100 years ago this week, the poet Edward Thomas died at the Battle of Arras in World War One.

Although he is celebrated as a war poet, Thomas’ poems rarely dealt directly with the conflict.

Dr Stuart Lee of the Faculty of English Language and Literature and IT Services started the First World War Poetry Digital Archive, which crowdsourced over 7,000 items of text, images, audio and video related to the First World War for teaching, learning and research.

Dr Lee says Thomas is a significant poet from the war era because, unlike the war-focused poems of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, his poetry represents what so many people back in the UK felt during the war.

'I think he’s a wonderful poet and he certainly deserves recognition because from that period he points us to another side of the war, the people who were at home who could just see the effects and playing on their mind,' he says.

'In poems like Rain and Owl he clearly is at home but his mind is going to those men on the front who are suffering for him and suffering for his country.

'He also presents probably what many people felt in terms of the attitudes of the war – he is not jingoistic and at the same time he’s not a pacifist, he’s right in the middle saying I don’t hate Germans and I don’t love England in the way the newspapers want me to, but I need to fight.

'It focuses us on the discussion of what we mean by a war poet and war poetry. We tend to think of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon and the likes because they were competent poets and they write about their experience in the trenches, but of course the war like all wars affected people who never actually served, who were on the home service, or who just experienced the war.

'Thomas was one of those men who was tackling a great problem which many people had to face up to, of what involvement he should have in the war.'

Dr Lee was interviewed about Edward Thomas on the BBC World Service this week. The full interview can be found at 48 minutes 30 seconds.

- ‹ previous

- 99 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria