Features

Professor Sally Shuttleworth, of Oxford's English faculty and St Anne's College, writes for Arts Blog about John Ruskin's role as an environmental campaigner. The Victorian art teacher and social reformer, who had strong views on the environmental impact of industrialisation, is the subject of a conference held in Oxford on Friday (8 February), the bicentenary of his birth.

In 1870, the historian J. R. Green, who had been exiled to the south of France for his health, wrote to a friend about startling events in Oxford:

I hear odd news from Oxford about Ruskin and his lectures. The last was attended by more than 1000 people, and he electrified the Dons by telling them that a chalk-stream did more for the education of the people than their prim “national school with its well-taught doctrine of Baptism and gabbled Catechism.” Also “that God was in the poorest man’s cottage, and that it was advisable He should be well housed.” I think we were ten years too soon for the fun!

Green’s glee at this ‘electrification’ of the Dons is palpable. The lectures to which he refers were John Ruskin’s, ‘Lectures on Art’ delivered in February and March 1870, by Ruskin in his role as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art. As Green’s summary highlights, the study and practice of art, for Ruskin, could never be separated from care for the natural environment, or concern for the material conditions of the poor. Ruskin raged against the ugliness, pollution and appalling living conditions created by industrialisation, and his argument that cities should have a ‘belt of beautiful garden and orchard round the walls’ so that ‘from any part of the city perfectly fresh air and grass and sight of far horizon might be reachable in a few minutes’ walk’ influenced the Garden Cities movement in the twentieth century, and the establishment of the principles of the Green Belt, which are under such pressure at present.

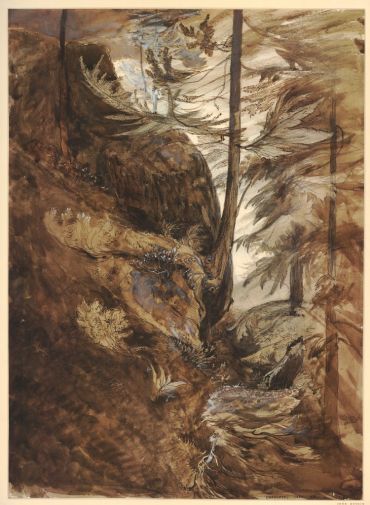

John Ruskin, Chamonix; hill with trees sloping upwards to l. 1850 Pen and brown ink, with brown wash, touched with white, over graphite

John Ruskin, Chamonix; hill with trees sloping upwards to l. 1850 Pen and brown ink, with brown wash, touched with white, over graphiteImage credit: British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Ruskin is often treated as a lone prophetic voice, but in the ERC project I run, ‘Diseases of Modern Life: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives’, we are uncovering a hidden history of environmental campaigning, to be found in the neglected records of sanitary reformers. The ‘diseases’ we look at are those of both body and mind produced by the pressures of modernity: stress, overwork, and information overload, but also ‘diseases of impure air’, and all the problems created for health by smoke pollution and insanitary living conditions. Ruskin, together with his friend Henry Acland, who was Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford, form part of this picture, as do all the local ‘citizen scientists’, patiently taking daily readings of sunlight hours for years on end in order to show the effects of smoke pollution, or the vicar who encouraged all his parishioners to acquire gauges so that they could measure air quality.

Ruskin, it has to be said, had a love-hate relationship with science: he quarrelled violently with John Tyndall over glaciers, and had contempt for Darwin’s materialism, but the close scrutiny of the natural world, upon which all his work was based, had much in common with the practices of science. To celebrate the bicentenary of his birth, we will be holding a conference on Friday 8 February at the Oxford Museum of Natural History (in partnership with the University of Birmingham Centre for Nineteenth-Century Studies), on ‘Ruskin, Science and the Environment’, to be followed at 6pm by a public lecture on ‘Ruskin’s Trees’ by Professor Fiona Stafford, author of The Long, Long Life of Trees. It is fitting that the conference is to be held in the Museum since it was built in the 1850s on principles drawn in part from Ruskin’s writings on nature and architecture, with Ruskin himself taking an active role in its design and decoration, as a tour by Professor John Holmes tour will highlight. The conference will be accompanied by an exhibition giving a rare opportunity to see designs for the museum by Ruskin and others, including the Pre-Raphaelite artists Thomas Woolner, Alexander Munro and John Hungerford Pollen.

To book for the conference click here, and here for the 6pm public lecture. Further information about both events can be found on the project website.

Louie Fooks, Humanities and Healthcare Policy Officer for Oxford Healthcare Values Partnership, discusses how a new report by Oxford University’s Healthcare Values Partnership and the Royal College of Physicians on ‘advancing medical professionalism’ can help address some of the problems faced by doctors and the NHS

The government’s Long Term Plan for the NHS, published earlier this month, sets out its vision for a quality health service able to cope with an ageing and expanding population. But, as many commentators point out, without the workforce it needs to support it, the plan will not meet its objectives.

More than 100,000 healthcare posts are currently vacant across the NHS and the number is likely to rise after Brexit. Indeed, the difficulty of recruiting, retaining, and ensuring the well-being of doctors has recently been described as a ‘crisis’ – with health organisations warning it’s a greater threat to the NHS than lack of funding.

Nationally, a quarter of doctors in training say they feel burnt out by high workloads and many are planning to reduce their hours or leave the profession early. And doctors report working in a culture of blame and fear which is jeopardising patient safety and discouraging learning and reflection.

Yet all this is set against a background of an ageing population with complex health needs – increasing the demands we put on doctors and making it even more important that they can operate at their best. Healthy life expectancy at birth is currently 63 years (against overall life expectancy of well over 80), with nearly half the population living much of their older years managing one or more chronic health condition.

Claire Pulford is the incoming Director of Medical Education for Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and explains the situation here. She says: 'Oxford and Thames Valley is lucky not to have some of the recruitment challenges to our medical training programmes which are faced by other parts of the country, but we still see vacancies and rota gaps in many essential specialities such as acute and emergency medicine. In recent years, there has been a marked drop-off after Foundation-level training, with doctors choosing not to move immediately into more senior or specialist training posts. And morale and engagement are adversely affected, with high levels of burn-out increasingly evident.'

Medical professionalism – part of the solution

How then should we prepare and educate students and junior doctors for modern medical practice – and enable doctors to maintain professional satisfaction throughout their careers? Advancing Medical Professionalism (AMP), argues that enabling and supporting doctors to develop their professional identities is an important part of the answer.

AMP took as its starting point the RCP’s 2005 definition of professionalism as the ‘set of values, behaviours and relationships that underpin the trust the public has in doctors’. It built on this with a series of workshops with healthcare staff, patients and other stakeholders to explore what professionalism might mean for doctors in 2018 and beyond.

The RCP’s Dr Jude Tweedie, co-author of AMP, says: 'Medical professionalism is extremely hard to define. As doctors, we recognise immediately when it’s absent and instinctively know that it’s essential to great patient care and physician satisfaction – but it can be very hard to quantify. So, we went out to talk not only to doctors, but to patients, academics, practitioners and others to find out what they thought.

'The process was really fruitful and helped us identify seven key aspects of doctor’s working lives essential to professionalism, highlighting the many different roles we expect our modern doctors to fulfil. From this we were then able to develop practical strategies and approaches to promote professional values, skills and attributes in each area.'

Seven key aspects of professionalism. Doctor as:

• Healer

• Patient partner

• Team worker

• Manager and leader

• Patient advocate

• Learner and teacher

• Innovator

Claire Pulford comments: 'The General Medical Council’s Generic Professional Capabilities have been adopted into the medical curriculum and give a much-needed basis for embedding professionalism in education and training. Advancing Medical Professionalism provides an excellent resource to support this – to start conversations with students, trainees and other colleagues – and help individuals, teams and institutions to reflect on, and develop, their practice. In Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust we intend to use the AMP report as a toolkit to inform our development programmes for trainees and trainers; and to explicitly reference it in our teaching, training, research, and Quality Improvement initiatives.'

Professor Joshua Hordern, of Oxford University Theology Faculty and the Oxford Healthcare Values Partnership, sits on the RCP Committee for Ethical Issues in Medicine and co-authored the AMP report. He believes passionately that humanities disciplines can provide vital insights into the modern health care challenges we face. Hordern says: ‘Most doctors go into the profession with a strong sense of vocation and commitment. But heavy workloads and the increasingly complex context in which they practice take their toll. We hope the approaches in AMP can support doctors in sustaining values of compassion, respect and integrity, developing their vocation and professional identity, and refreshing their joy and confidence in the work they do.'

Advancing Medical Professionalism was authored by Dr Jude Tweedie, research fellow to the president, RCP; Professor Dame Jane Dacre, immediate past president of the RCP; and Professor Joshua Hordern, Associate Professor of Christian Ethics, University of Oxford. Professor Hordern leads the Oxford Healthcare Values Partnership and is a member of the RCP’s Committee for Ethical Issues in Medicine. Dr Richard Smith added to, and extensively edited, the report.

Oxford Healthcare Values Partnership is a partnership of University of Oxford researchers and healthcare staff seeking to understand and improve the ethos of healthcare services. Advancing Medical Professionalism was developed as part of the healthcare and humanities programme, generously supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

A rare 15th-century French Gothic coffer, believed to have been used for housing and transporting religious texts, has been acquired by the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries. Thousands of manuscripts and printed books survive from medieval Europe but just over 100 book coffers are known to be in existence. This book-box forms the centrepiece of a new display at the Bodleian’s Weston Library, titled Thinking Inside the Box: Carrying Books Across Cultures, which opened on 19 January and continues until 17 February 2019.

The coffer is a small wooden chest complete with a vividly coloured woodcut print depicting ‘God the Father in Majesty’. It was acquired from a dealer with support from Art Fund, the Bodleian’s Kenneth Rose Fund and the Friends of the Bodleian.

The Bodleian Libraries hold one of the largest collections of medieval manuscripts and early printed texts in the world, but boxes and other objects for the storing and transporting of books rarely survive. This is the first coffer of its kind to enter the Libraries’ collections. It is hoped that the coffer will help researchers, curators and visitors understand more about how items were stored, transported or used in the very early days of printing in Europe.

This acquisition gives us greater insight into the ‘everyday life’ of books and print culture more broadly. The coffer provides a link between books held at the Bodleian and cultural objects which were once united, but now usually live apart in libraries and museums around the world.

The coffer features a vivid woodcut print.

The coffer features a vivid woodcut print.Dr Christopher Fletcher, Keeper of Special Collections at the Bodleian Libraries, said: “The Bodleian collects books and manuscripts but also objects which helps us to understand the history and culture of the book – how they were kept, used, moved and understood. The coffer is a remarkable item which is both utilitarian and devotional and preserves an exceptionally rare woodcut in its original context. Among other things, it shows us that our preoccupation with carrying information around with us in mobile devices – including texts and images – is nothing new.”

The majority of surviving book chests date to the 1500s. The Bodleian’s 500-year-old coffer is made of wood covered in leather, reinforced with iron fittings, hinges and a lock. The inside lid contains a fragile image dated to c.1491 and a prayer, in Latin, used as a chant on special feast days. Only four impressions of this woodprint are known to survive, dating from the very early days of printing in Europe.

What the coffer was designed to hold remains a mystery. It could have held a richly illuminated Book of Hours, alongside other Christian devotional books or materials, such as a rosary. The book would have been protected in the chest by a lining of red canvas, which survives still largely intact. Some surviving coffers contain hidden compartments and straps suggesting that they may have held additional relics and were designed for carrying.

Dr Cristina Dondi, Professor of Early European Book Heritage at the University of Oxford and Oakeshott Senior Research Fellow in the Humanities at Lincoln College, said: “Very few original woodblock prints from this period survive and each is rich in meaning, complex and exceedingly rare. So to be able to study one still attached to a physical object of this nature is truly exceptional.”

“This coffer dates to a time when devotional materials were at the crossing between the medieval and the modern period, between art made by hand and by mechanical means. The new arrival will join the right environment to further its investigation and understand how to place it within a European tradition,” said Professor Dondi, who is also the Principal Investigator of the 15cBOOKTRADE, an ERC-funded project which studies the impact of the printing revolution on early modern European society.

The Bodleian Libraries will make the coffer available to researchers; the Libraries already support programmes of scholarship in early printed books through its Centre for the Study of the Book and its Visiting Scholars programme, and funds academics to delve deeper into the Libraries’ unique manuscript holdings and early printed books.

Members of the public can see the coffer at the free Thinking Inside the Box display, which also features about a dozen fascinating boxes, bags and satchels from around the world that have been used to carry books through the ages. Visitors can see such treasures as Qur’anic manuscripts with specially designed satchels, a palm leaf manuscript from West Java inside a beautifully carved, lacquered and painted box, the Kennicott Bible with a lockable wooden carrying case, and a miniature artist’s book which springs from a faux matchbox to reveal an accordion-fold of 13 wood engravings. For more information, including opening times, visit https://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/whatson/whats-on/upcoming-events/2019/jan/thinking-inside-the-box.

There will also be a special Thinking Inside the Box activity day on 2 February, offering visitors of all ages the opportunity to meet expert curators, explore the technology behind creating modern boxes for library and museum objects, watch an artist demonstrate the technique of traditional wood engraving, and create their own miniature matchbox book. For more information, visit https://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/whatson/whats-on/upcoming-events/2019/feb/thinking-inside-the-box-activity-day

A 3D model and photos of the coffer are available to view on the University of Oxford’s Cabinet website, which uses digitisation to make museum collections more accessible for teaching and research. View the coffer at https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/gothiccoffer. In addition, Cabinet also includes a 3D model and photos of a deed box, which features in the Thinking Inside the Box display. View the deed box at https://www.cabinet.ox.ac.uk/deedbox.

Researchers at the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine (MRC WIMM) have developed technology that allows scientists to explore the complex 3D structure of DNA in Virtual Reality. In a newly published pre-print, the team describes their tool, which is now freely available to all.

Working out the sequence that makes up genetic code is now routine in medical research, but the sequence is not the whole story; genes are also turned on and off by physical interaction between specific parts of DNA.

Consider chromosome 1, just one of the 23 paired chromosomes we have: An intricately folded chain of 250,000,000 nucleotides containing 4,220 genes which physically interact with each other in three dimensions.

The molecular origami of these interactions needs to be very precise, and mistakes can literally be the difference between life and death. Changes in the folding of DNA is believed to be associated with a range of diseases, including cancer.

All 22,000 of the genes we carry are contained within 2 meters of DNA, which is similarly packaged into complex folds and whorls in the nuclei of every one of the 37 trillion cells of the body.

Visualising in 3D

Working out the 2D sequences of nucleotides that make up the genetic code in our DNA is crucial in understanding how genes work, but understanding the physical interactions between the folds of DNA requires a leap into a new dimension.

That’s where Stephen Taylor and Jim Hughes, from the Centre for Computational Biology at the MRC WIMM, come in. They put their expertise in computational biology and gene regulation together with experts in real time computer graphics and human-machine interaction at Goldsmiths, University of London, to produce CSynth. CSynth is an interactive tool that allows scientists to visualise a whole chromosome of DNA in 3D and track points of physical interaction.

Unlike comparable tools, CSynth combines interactive modelling with the ability toconnect what they see in their 3D model with the DNA sequence information freely available online. Users can dynamically change parameters and compare models to see how this might affect genes and other elements in the DNA, such as the switches that turn genes on and off. An additional feature of CSynth is that it combines its state-of-the-art computational model with Virtual Reality. This means that researchers can virtually step inside the DNA structure and explore and manipulate DNA molecules in a new way.

Learning tool

The potential to really visualise DNA also makes CSynth an excellent learning and public engagement tool, especially when combined with the Virtual Reality. Thousands of people have experienced CSynth at the Royal Society Summer Exhibition, the Cheltenham Science Festival and many schools and institutes.

The Oxford team has already collaborated with other researchers at the MRC WIMM to examine how the DNA that codes for part of the haemoglobin complex (the molecule that transports oxygen in red blood cells) folds in 3D, and how the folding changes in different cell types.

What’s new is that the software is freely available to anyone who has access to a web browser. Any scientist can now upload their own data to model and explore at http://csynth.org/. It doesn’t need software installation and is extremely fast to run. The researchers hope that this public web interface makes CSynth useful for education and learning too, and that researchers can share their models online.

But perhaps most importantly, CSynth will help scientists at Oxford and beyond identify potential structures and genetic elements associated with disease and to understand the impact of DNA structure on function.

In the summer of 2015, Peter Frankopan published his book The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, described by Bloomsbury as ‘a major reassessment of world history in light of the economic and political renaissance in the re-emerging east’.

Just three-and-a-half years later, the book has been named one of the 25 most important works translated into Chinese over the past 40 years. The Silk Roads takes its place on the list alongside literary classics including Pride and Prejudice, The Great Gatsby, Catcher in the Rye and One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Professor Frankopan, Professor of Global History at Oxford and Senior Research Fellow at Worcester College, described himself as ‘flabbergasted’ to be chosen for the list, which was compiled by Amazon China on the 40th anniversary of Chinese reform and opening-up.

He said: ‘When I was told about it, I thought it was a wind-up. Many of the books on the list are ones I admire hugely, and to be mentioned in the same breath as The Great Gatsby, One Hundred Years of Solitude, or A Brief History of Time is genuinely astonishing. I realise that tastes come and go, so who knows if it will still be mentioned in 25 years’ time. But it is a great testimony to the importance of the humanities in general, of history, and of the impact that historical writing can have far beyond the Senior Common Rooms of Oxford.’

The Silk Roads challenged Eurocentric views of world history, shifting the focus east of the Mediterranean. It became a bestseller in a host of countries and categories, and was met with widespread acclaim. A follow-up work, The New Silk Roads, was released last year and explores more recent events.

In Professor Frankopan’s own words, by writing The Silk Roads he was simply ‘trying to explain how the past looks from the perspective of the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East, Central Asia and beyond’.

He added: ‘I’ve been a Senior Research Fellow at Worcester for nearly 20 years, and Director of the Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research since it was founded nearly a decade ago. I simply wanted to explain why the regions, peoples and cultures that I work on are not just interesting, but also important. It was not easy to write at all and I spent many, many late nights at my computer trying to work out if it was possible. I never thought for a moment about whether lots of people would read it. But I did think it was worth trying to write!’

Reflecting on the book’s success, Professor Frankopan – who has just published an illustrated version of The Silk Roads for younger readers – said: ‘It’s been a lovely – if sometimes strange – experience. This week alone, I’ve had tweets or Instagrams from people sending pictures of my book from bookshops in Norway, Indonesia, Nigeria, India and Pakistan, and lots of emails from all over the world, often asking questions about what to read next, or for more information about a specific location, which I always try to answer if I can. But I don’t think it has affected me – we have four children, who do a pretty good job in keeping my feet on the ground. And because, like most academics, I always have deadlines for articles or chapters in books, there’s never a great deal of time to bask in the sunshine as I’ve got too much to be getting on with as it is.’

- ‹ previous

- 60 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria