Features

Bernard Naughton and Dr David Brindley from Oxford University’s Saïd Business School and Medical Sciences Division discuss the problems of identifying fake, substandard and expired medicines.

Pharmaceuticals are critical to our society, supporting patient health and an innovative industrial sector. Research and development (R&D) by leading pharmaceutical companies totals hundreds of billions of pounds globally each year. These extraordinarily high development risks contribute to the sometimes high reimbursement costs of medicines. Therefore, it comes as no surprise, that as with most large and lucrative industries it attracts its share of bootleggers.

Counterfeit medicines are becoming a serious concern worldwide, and have increasingly been appearing through the legitimate pharmaceutical supply chain, including community and online pharmacies. This not only poses a health threat to the public but also to the balance sheets of pharmaceutical companies.

The Pharmaceutical Security Institute report that between 2011 and 2015 the global incidence of drug counterfeiting has increased by 51%, with 2015 seeing the highest levels of counterfeiting to date - a 38% increase when compared with 2014. In the UK supply chain alone, 11 cases of fake medicines were detected between 2001 and 2011.

These products vary immensely - fake medicines may be contaminated, contain the wrong or no active ingredient, or could contain the right active ingredient at the wrong dose. In any of these scenarios, patient safety is compromised.

There are a variety of methods currently used to detect counterfeit medicines, including laboratory-based methods and SMS texting. The detection of counterfeit medicines by customs officials usually occurs as a result of intelligence or random checks, after which suspect medicines are sent away for laboratory-based analysis. Advancing technology has made a variety of techniques available which include spectroscopy, chromatography, SMS, handheld or portable laboratories, radiofrequency identification and serialisation.

The recent advent of the EU Falsified Medicines Directive (FMD) mandates that all prescription medicines are serialised, verified and authenticated from February 2019 in all member states. Serialisation is the process of identifying a medicine with a unique code printed onto the medicines pack and verification is the process for identifying and checking that code. The term ‘authentication’ relates to the final scanning of a medicine and the subsequent decommissioning of a product at the point of supply to the patient to ensure authenticity.

In our own recent study, published in BMJ Open, we tested the effectiveness of a medicines authentication technology in detecting counterfeit, recalled and expired medicines within a large UK hospital setting. More than 4,000 serialised medicines were entered into a hospital dispensary over two separate 8-week stages in 2015, and medicines were authenticated using secure external database cross-checking, triggered by the scanning of a 12-digit serial code. In this instance, 4% of medicines included were pre-programmed with a message to identify the product as either expired, pack recalled, product recalled or counterfeit.

We found that the operational detection rate of counterfeit, recalled and expired medicines scanned as a combined group was between 81.4% and 87%. While the technology's technical detection rate was 100%, not all medicines were scanned, and of those that were scanned not all that generated a warning message were quarantined. Owing to an operational authentication rate of 66.3%, only 31.8% of counterfeit medicines, 58% of recalled drugs and 64% of expired medicines were detected as a proportion of those entered into the study.

The detection of medicines was largely effective from a technical perspective; however, operational implementation in a complex environment such as a secondary care pharmacy can be challenging.

The study highlighted significant quality and safety issues with this detection approach. There is a need for further research to establish the reasons for less than absolute authentication and detection rates in the hospital environment to improve this technology in preparation for the incumbent EU (2019) and US (2023) regulative deadlines.

In order to safeguard patients against potentially dangerous pharmaceuticals, it’s clear that we need to find an iron-clad detection system to filter out fake and expired products. It will also be vital to address the implementation approach to this technology whilst educating those who will use the system effectively and efficiently.

While we can’t stop the production of fake medicines, we can and must safeguard patients from them.

The full paper, ‘Effectiveness of medicines authentication technology to detect counterfeit, recalled and expired medicines: a two-stage quantitative secondary care study,’ can be read in the journal BMJ Open.

We would like to thank Prof. Stephen Chapman (Keele University), Prof. Sue Dopson (Saïd Business School) and Dr. Lindsey Roberts (Oxford Academic Health Science Network) for their support in this collaboration.

If you don't have the energy to mark Burns Night by going to a ceilidh or cooking haggis, neeps and tatties, Arts Blog has a suggestion for how to mark the day.

We asked Fiona Stafford, Professor of English Language at Literature at Oxford University, to suggest a Robert Burns poem to share with our readers.

She picked ‘To A Louse, On Seeing One on a Lady’s Bonnet at Church’ - and here it is.

'Burns speaks to modern readers very directly because his observations of humanity still ring true, while at the same time a relatively simple poem often turns out to have numerous layers and hidden jokes,’ she says.

‘In 'To a Louse', the speaker is riveted by the steady progress of the louse he spots in the very elaborate and highly fashionable bonnet of a young lady who is evidently hoping to make an impression.

‘As the poem continues, it becomes clear that the joke is not just on the young lady, who is unaware of her little visitor, but also on the speaker, who is much more interested in the young lady (and, indeed, where the louse may be heading) than in the service, not to mention the minister, who doesn't even merit a mention and thus seems to be commanding the attention of no one.

‘The famous concluding prayer - 'To see oursels as others see us' - arises naturally from the situation, and reads as a common-sense reflection, but there is a further joke in that it's adapted from the contemporary moral philosophy of Adam Smith.

‘The speaker who has been addressing the louse in broad Scots turns out to be very well read and up to date in his thinking.'

Professor Stafford is currently interested in Burns and the natural world. Her latest book, ‘The Long, Long Life of Trees’, was published by Yale University Press last year. She has found that Burns has a real affinity to nature.

‘As a farmer, we might expect Burns to have had a fairly practical attitude to the land, but many of his poems reveal a sensitivity to the beauty of the local landscape and wildlife, as well as a rare ability to sympathise with non-human perspectives on the planet,’ says Professor Stafford.

‘Burns is one of the first poets to show concern over the clearance of woodlands by contemporary landowners and to influence attitudes by speaking up in verse for the plantation of indigenous trees. He was, in this way, an early voice for the environment and his enormous popularity and stature as Caledonia's Bard meant that his views carried weight.’

For those new to tech culture, or even just interested in how the industry and its many inventions work, the associated terminology can sometimes feel like an unknown, foreign language. But, like most things in life, when you remove the jargon and insert short, simple explanations for what things really mean, they become immediately less intimidating and more accessible to all.

The ScienceBlog tech nine is designed to give the less scientifically inclined a basic introduction to some of the industry’s more commonly used terms. This glossary will not guarantee that the reader speaks fluent techie overnight, but it is a useful conversation aid and gateway into the industry.

The name given to a fast growing, new or emerging company that has launched a product in response to a marketplace need or opportunity - think AirBnB, borrowmydoggy.com and Uber. Startup companies tend to rely on the backing of other more established businesses or investors to fuel early development.

2) Unicorn

Forget fantastical mystical horned horses, in the land of technology, the word is used to describe a startup company valued at over $1 billion. How do the two connect, you might ask? Well, one’s a mythical and much-sought after beast which countless authors have written extensively about, and the other’s a horse with a cone on its head. But, when you join the dots and think of them symbolically as rare (so rare, many see them as too good to be true), wonderful things, a picture emerges. For investors, unicorns are the ultimate business opportunity. Mention one in passing to a tech insider, and watch their eyes light up.

While more often spotted in the tech forests of Silicon Valley, Oxford University has its own unicorn in the shape of handheld DNA sequencer developer Oxford Nanopore, which was valued at £1.25bn after its recent £100m investment.

3) Tech cluster / innovation community

The ultimate power gathering, a tech cluster is the name given to a group of thriving tech companies, situated in close proximity to both each other and surrounding a renowned research university. The most famous example is California’s Silicon Valley, home to tech trailblazers’ eBay, Google, Facebook and Pixar, to name a few. Slightly lesser known and unfortunately named by comparison, the UK’s Silicon Roundabout, also known as Old Street Roundabout in East London, is growing rapidly and includes CrowdCube and Deliveroo.

Home to the top ranked university in the world, it is little surprise that Oxford is one of the most active tech clusters in Europe. The region is buzzing with innovators, entrepreneurs, and investors, with a rapidly increasing level of activity.

4) Spinouts

In the world of university innovation, a spinout is a company that has university research underpinning its core product of service. Markedly different to a regular startup, spinouts require a strong bond with the academic community to succeed and significantly more resources and time to get to market, but the overall chance of success is much higher and the impact of such companies can be literally world-changing. A great example of a successful spinout is Oxford University’s very own Oxbotica, who develop next generation autonomous vehicles.

Oxford University Innovation (OUI), the university’s research commercialisation company, is one of the most impactful offices of its kind, worldwide. In 2016, it set a European record for spinout generation, and will this year celebrate 30 years of operation, during which it has helped launch over 150 companies based on Oxford research.

5) Incubator

In the same way that hospital incubators protect babies, business incubators offer emerging entrepreneurs a safe space to grow, develop and test their abilities, until they are strong enough to fly solo. In the tech world, the term describes a flourishing business that supports the development of new enterprises by providing services and outreach support that make them stronger. Examples include, training, office space and resource.

Incubators, such as the one situated at OUI, play an increasing role in university life. At the start-up incubator, rising entrepreneurs receive bespoke support in a protected environment, where they can then benefit from learned experience, expert training and even financial support.

Not to be confused with the other, university-specific VC, venture capital describes a type of enterprise funding given to new or developing companies by more established, financially fluid organisations. Investors look at a chosen business and weigh up its potential, in terms of the number of employees and revenue generation, in return for financial equity. For a lot of emerging and startup businesses, venture capital is essential to their survival in the early stages of operation.

Although many dream of getting rich overnight, mindful investors know that in business, sustainability is the key to success. A counter balance to the short term outlook of VC, patient capital plays the long game and has a much longer view on returns from investments. This sort of investment has become crucial to supporting spinouts, which have a much longer development cycle than a traditional startup.

An example of patient capital is Oxford Sciences Innovation (OSI), which manages the university venture fund of Oxford University. Focused entirely on supporting spinouts, it is the largest such fund in the world.

8) Seed Funding

As the name implies, seed funding is financial support provided right at the start of a company’s lifecycle, to help them grow. Increasingly seen as a way to get companies off the ground, seed investors are typically high-net worth individuals (also known as angel investors) or small, dynamic funds focused on this pivotal early stage.

9) Stealth Mode

Keeping a secret, a secret, is not always easy, and a business in “stealth mode,” is essentially working to protect a big one of its own. The term is often used when a company wants to withhold information from competitors or to avoid sharing details about a new development. It is particularly common for startup companies to work this way, ahead of launch, while they test the water and build their brand and product identity.

“Siri, will it rain today?”, “Facebook, tag my friend in this photo.” These are just two examples of the incredible things that we ask computers to do for us. But, have you ever asked yourself how computers know how to do these things?

Machine learning is not a new concept but it is constantly evolving and the potential benefits of its capability are increasing by the second. A form of artificial intelligence, it provides computers with the ability to learn through experience, without being explicitly programmed to perform a task. As the computer receives more data, its algorithms become more finely tuned and over time it begins to recognise patterns and solve problems on its own - without the use of a programme. The more finely tuned the algorithm, the more accurate the computer can be in its predictions.

In their latest animation, Oxford Sparks, the University of Oxford’s digital science portal, outline how researchers have combined the power of statistics and computer science, to build algorithms capable of solving complex problems more efficiently while using less computer power.

Using machine learning this way is already informing medical diagnosis and strengthening the speed and capability of smartphones and social media, but its scope to revolutionise the world seems limitless.

View the video and learn more about the power of machine learning here:

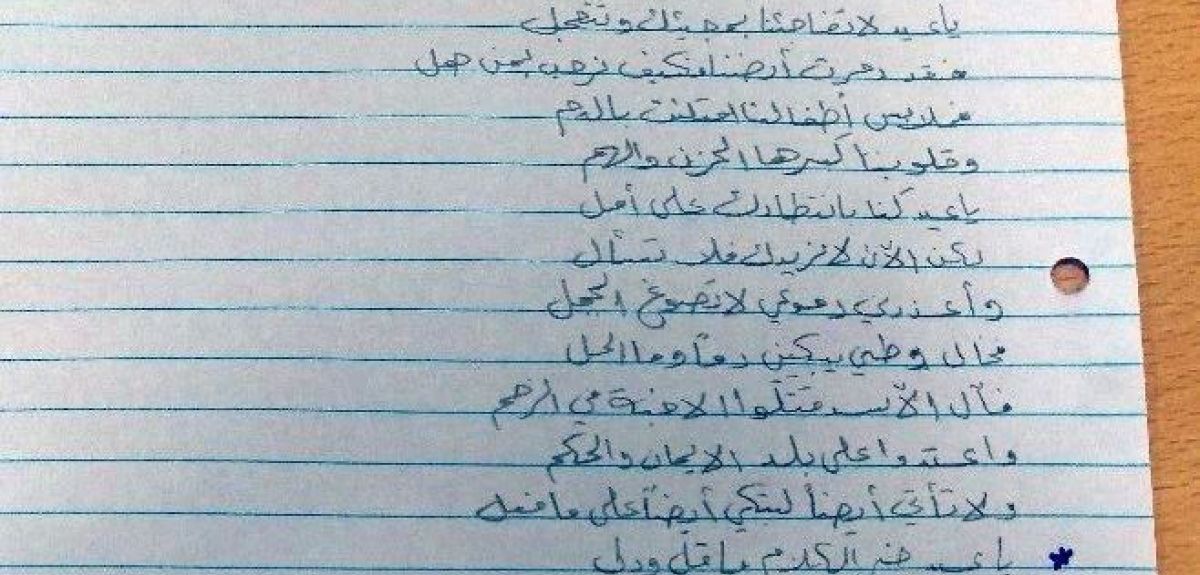

Oxford students have helped to put on a multi-lingual poetry writing workshop at Oxford Spires Academy.

Pupils at the state secondary school in East Oxford were encouraged to express themselves through poetry in different languages.

The workshop was a collaboration between Oxford University’s Creative Multilingualism research project and Oxford Spires Academy’s poetry hub. It was led by award-winning Iraqi poet, Adnan Al-Sayegh, who has lived in exile since 1996 and been based in the UK since 2004.

‘One of the main aims of the Creative Multilingualism project is to show that the linguistic diversity in UK schools, and the UK in general, has tremendous potential both in terms of fostering productive communication across cultural groups, and in terms of creative thinking and writing,’ says Professor Katrin Kohl, director of the project.

‘These workshops encourage students to be creative in their own language and across languages.’

32 languages are spoken by children at Oxford Spires Academy, and the majority do not have English as their first language.

Students from Syria, Algeria, Tanzania, Pakistan and Sudan heard Mr Al-Sayegh speak about the importance of poetry, which he considers to be a basic human need.

He described how poetry is not restricted to the written word but is found in music and on the street, with the power to build bridges between people, as having a poetic heritage is something shared by all cultures.

A more detailed summary can be found here.

- ‹ previous

- 105 of 252

- next ›

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria