Credit: Shutterstock

Trash talk: 'no time to waste'

By Alexis McGivern, Environmental Change and Management MPhil at the Environmental Change Institute

I have an obsession that I’ve given up trying to beat: I’m fascinated by trash. I started low-waste and plastic-free living in 2013 with a month-long challenge and have since oriented my career and studies around the captivating problem of over-consumption. In 2015, I started working on plastic pollution issues at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in a position funded by the Gallifrey Foundation, a Swiss-based philanthropic foundation.

My current research at Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, looks at the environmental justice implications of waste management interventions, examining the relationship between social deprivation and the location of waste incinerators in the UK.

Plastic pollution has captured public attention like few other environmental crises. Those of us in this field pre-2016 saw the ‘Blue Planet Effect’ happen in real-time: at IUCN, we went from trying to convince funders that plastic pollution was a problem worth caring about to having our cup runneth over with funders who wanted to make a splash on the current hottest environmental problem.

Unless we can rapidly halt plastic production, we need to rapidly transition towards a plastic economy that is circular.

In 2018, I represented IUCN in negotiations at the UN for an international treaty on plastics and saw firsthand how complicated it is to reach meaningful consensus between industry, governments and environmental NGOs. Despite these difficulties, there are a huge number of international, national and corporate commitments that all work towards the goal of reducing the amount of plastic leaking into our environment. But how effective are these lofty ambitions at managing this ever-growing problem?

The Plastic Pollution Emissions Working Group (PPEG) is a group of experts who wanted to pin down how effective different interventions actually are at reducing the amount of plastic into aquatic ecosystems. We knew we wanted to pin down how much plastic was currently leaking into all aquatic ecosystems: the oft-quoted Jambeck et al (2015) figure of between 8 -12 million metric tonnes (Mt) annually did not include lakes and rivers, and also needed to reflect 2020 numbers of production and consumption. We found current annual leakage to be between 24-35 million metric tonnes, which is more than three times the number currently used to inform policy responses (Jambeck et al. 2015). It was an incredible experience to work with authors from that seminal study (Jenna Jambeck and Kara Lavender Law) and to be a part of generating new insights for academics and practitioners in this space.

The Plastic Pollution Emissions Working Group (PPEG) is a group of experts who wanted to pin down how effective different interventions actually are at reducing the amount of plastic into aquatic ecosystems. We knew we wanted to pin down how much plastic was currently leaking into all aquatic ecosystems: the oft-quoted Jambeck et al (2015) figure of between 8 -12 million metric tonnes (Mt) annually did not include lakes and rivers, and also needed to reflect 2020 numbers of production and consumption. We found current annual leakage to be between 24-35 million metric tonnes, which is more than three times the number currently used to inform policy responses (Jambeck et al. 2015). It was an incredible experience to work with authors from that seminal study (Jenna Jambeck and Kara Lavender Law) and to be a part of generating new insights for academics and practitioners in this space.

We wrote down a laundry list of policy interventions, from bag bans to an internationally harmonised recycling standard, and got to work quantifying their impact at reducing the mammoth number leaking into our aquatic ecosystems each year

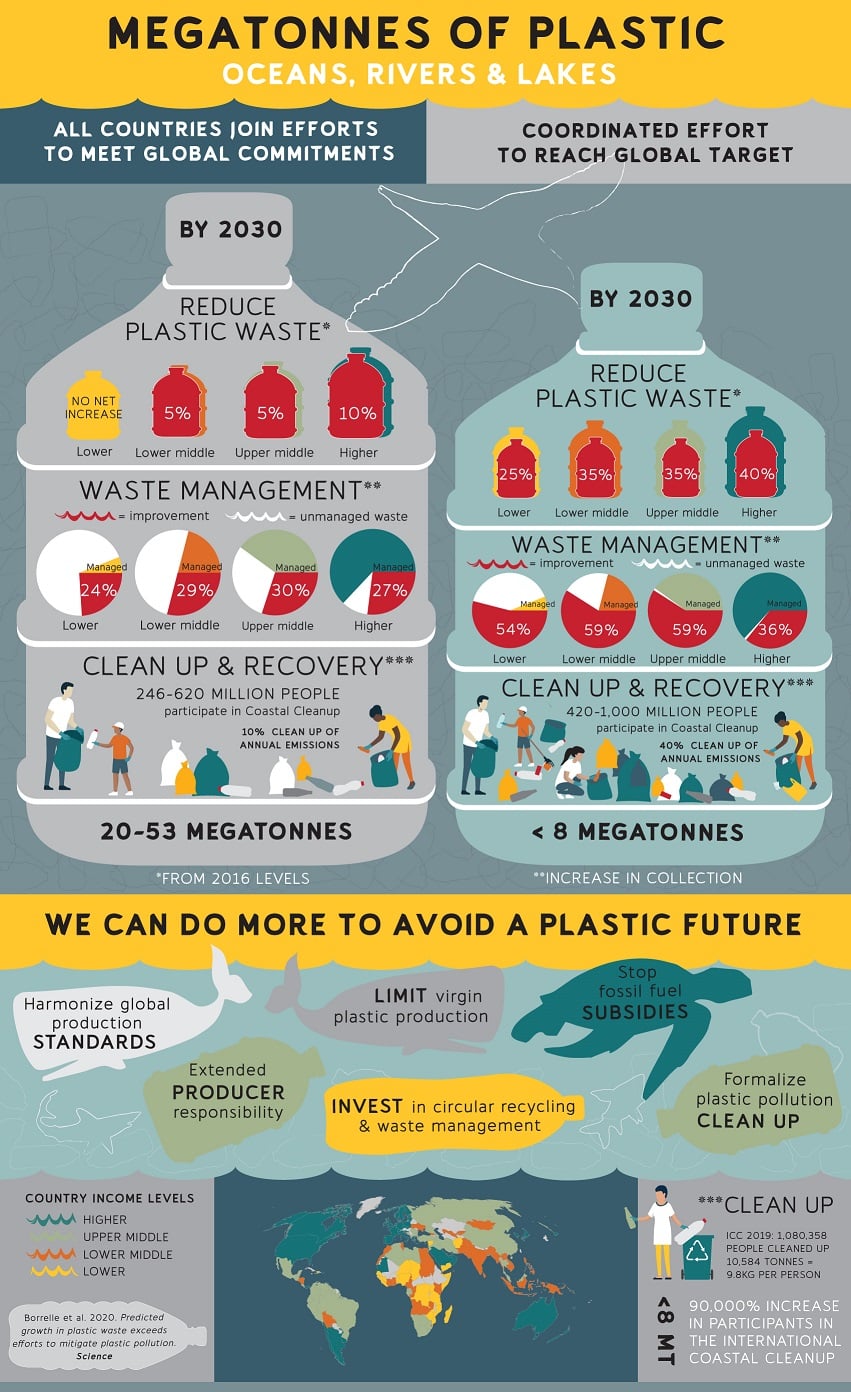

Using a cross section of interventions across three categories (reductions in plastic waste generation, waste management interventions and recovery interventions), we compared multiple reduction scenarios to a business as usual scenario. We wrote down a laundry list of policy interventions, from bag bans to an internationally harmonised recycling standard, and got to work quantifying their impact at reducing the mammoth number leaking into our aquatic ecosystems each year.

We found that even under current ambitious global commitments, between 20-53 million metric tonnes of plastic will enter aquatic ecosystems annually by 2030. That’s the same approximate weight as up to one million ‘Hercules’ airplanes!

This demonstrates that our current commitments are not enough to deal with increasing production of virgin plastics, rising consumption rates, current inadequate waste management efforts, and population growth.

Another scenario we generated sought to keep annual plastic emissions below 8 million metric tonnes, the estimated global emissions in 2010 to the oceans, and the number that prompted a wave of action and commitments on plastic pollution.

We found that the global community would need to make profound, systemic changes to achieve this target:

- Almost halving the amount of plastic waste going to our trash cans by 2030;

- Increasing our waste management capacity by an additional 36-59% each year (in low-income countries, the capacity increase would need to be tenfold);

- And capturing at least 40% of plastic leakage through beach, river and lake clean-ups every year.

What does all of this tell us? There is no time to waste. Unless we can rapidly halt plastic production, we need to rapidly transition towards a plastic economy that is circular. End-of-life plastic products must be valued in order to avoid becoming waste, and clean-up strategies must expand beyond grassroots efforts into systematised efforts in order to catch inevitable leakage. We all must come together to transform the plastics economy and avoid these troubling futures.

Current Environmental Change and Management MPhil Alexis McGivern is a co-author on an article published in Science that quantifies the amount of plastic pollution in lakes, rivers and the oceans by 2030. See 'Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution' in Science.

The study demonstrates that plastic waste production is rapidly outpacing the ability to manage it. Even under the most ambitious current commitments, there will still be up to 53 million metric tonnes of plastic leaking into aquatic environments every year.