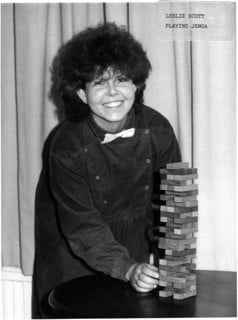

Credit: Sue Macpherson

Jenga: a tale of randomness and design

This month Senior Associate of Oxford’s Pembroke College, Leslie Scott, was honoured by her wildly popular invention Jenga being inducted in the US’s National Toy Hall of Fame. Sold in 117 countries across the world and loved by all ages, as a family- and pub-favourite, Jenga is now officially a classic.

Science Blog caught up with Leslie Scott, to find out how the game evolved and why its simple concept keeps people coming back for more.

How did Jenga come into being?

As a game, it evolved amongst my family when we were living in Ghana in the mid-70s. I moved to Oxford a few years later and had a set of these blocks and started to play it as a game. They weren't exactly like the Jenga blocks are now but the principle of the game was there.

I played a lot with friends here in Oxford. But it took a long time for the penny to drop that this didn't exist already as a game. People and children have obviously been piling up blocks of wood for years, but actually to turn that into a game, it just didn't exist.

So in 1982, I decided I was going to take this game to market. But that's when the issues started. I knew nothing about the toy industry and nothing about retail business. But I was just so convinced this was going to work.

What are the secrets to Jenga’s success?

Not many people realise this but each one of the blocks in the game are slightly randomly different from each other. And that's absolutely deliberate. Because without that, the game just really doesn't work. If they're all identical it just sits there. So that sort of randomness was a factor of the original, handmade wooden blocks.

I had to figure out how to mass market some of these flaws. Then there was the question of how many actual blocks there should be, plus their size. The original ones were slightly longer than Jenga blocks are now. That meant you couldn't assemble them three by three and make a stable tower to start with - there were gaps between each.

But I figured out that if you made them just slightly shorter you can square it up. So you can start with a fairly stable tower. The decision to go for 54 blocks was trial and error. You start with 18 rows and it just worked - I don't think there was anything more scientific.

How did you scale up production to maintain randomness?

I spoke to a carpenter I knew and asked him how would you do this. He came up with a very clever suggestion, which was to send the planks of wood through a sanding template that was not in itself 100% even. So these planks of wood would go through that template, and then be chopped up into the pieces.

The next stage was introduced by a group of people in Yorkshire at a place called Camphill. It's a sheltered community for adults with learning disabilities and other special needs - it's a movement all around the world. In Yorkshire they have a farm, they've got a dairy, but they also have a woodworking shop.

They had already been making wooden toys, and a person that I knew at Oxfam suggested talking to them. I went up and saw them and asked if they would be interested in doing this for me? And they said, “Yes”, provided that if it became successful, I took it elsewhere to be manufactured because they didn't want to spend the rest of their lives just churning out hundreds and thousands of the wooden blocks!

They came up with this idea of tumble polishing them. When you very lightly tumble polish it puts a nice sheen on them. It smooths the edges, but it doesn't smooth them totally - it introduces another level of slight inconsistency, so it's really clever.

I haven't seen how Hasbro make them now in vast quantities, but I understand it's not that different. This randomness is still built into it. People love playing with wood. There's that tactile element to it, but it's also actually key to the functioning of the game.

What do you think is Jenga’s enduring appeal?

I think it appeals because you can play it with anybody - as long as you've got a certain amount of dexterity. It still seems to require skills, but they're not skills that take a lifetime to learn. And plus, it is never the same. There's nothing inevitable about who's going to win. When you start the game you could make exactly the same moves, but it's not going to end up in the same way because of the randomness.

It's thrilling when you're teetering at 30 layers already. And it's terrifying it when it comes back to you.

Also, I didn't deliberately intend it to be a cooperative game. But if you watch people playing, once the tower gets beyond a certain height, most people end up wanting it to get higher. They really want it to get high, so it becomes almost like a team effort, in a funny way. The excitement comes in trying to get it as high as possible. Nobody deliberately wants it to fall over. So on one hand it could be considered a very competitive game, on the other hand, there’s actually quite surprisingly cooperative play involved. It's thrilling when you're teetering at 30 layers already. And it's terrifying when it comes back to you.

Where did the name Jenga come from?

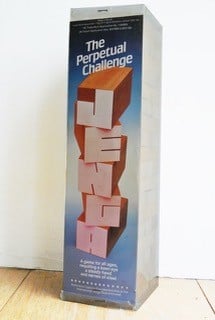

I grew up speaking Swahili and the word jenga is the imperative form of kujenga, the Swahili verb “to build.” When I first put it on the market, I called it ‘Jenga the perpetual challenge’. And the company that took it on - first of all Irwin in Canada, and then subsequently Hasbro worldwide - hated the word ‘perpetual’. They said Jenga doesn't mean anything and nobody in North America will understand what perpetual means either! So I had a bit of a battle with them and I ended up saying, “Okay, okay, okay, you don't have to call it perpetual.” Even though I actually really meant it – I’d thought about that hard. It is always a challenge. It's not the ultimate challenge, but it's always a challenge. But I have this feeling that by giving up on 'perpetual' I got away with keeping Jenga [laughs].

Do you feel that your childhood influenced the development of Jenga?

I think we should leave children to think and do things for themselves a great deal more than we do now.

When we were kids, the idea that every moment of the day was somehow timetabled wasn’t there. Even at school, there were large, large chunks of time where we literally went out and played, and we were not being supervised for every moment. And, personally, I think we've got the concept of education a wee bit wrong. I mean, I think we should leave children to think and do things for themselves a great deal more than we do now.

If you think about some of the toys that are now produced for children, there's an awful lot that have stories already built into them. I think it's interesting that the National Toy Hall of Fame (which has inducted 74 items), have quite a large number that don't have an inventor as such. There's things like the cardboard box, the stick, marbles. What they're trying to recognise are playthings that have actually contributed to genuine play, playful play.

I think the opportunity to be creative, or the environments in which you can become creative arise when somebody else hasn't told you how to think about something. I don't know how Jenga fits into that, but play is a subject that really interests me.

What is a play – what is a game?

We use terms like “Somebody's got to play the game” or we imply that incredibly serious things are games - like business is a game and life is a game. I think we need to be quite careful how we define what we mean by ‘play’ and make sure that if we are saying, “it's all a game” that at least we actually know what those rules are when we're playing this game. And we know when we're outside of that too.

The thing about a game is that you've agreed to take part in it, it is something voluntary. Secondly, you've got a set of rules that you've agreed that you understand, you're playing by that set of rules, you're playing within a confined space, a delineated area, you're playing for a certain amount of time. So there's a beginning and there's an end to it too.

How do you feel about Jenga entering the National Toy Hall of Fame?

I am thrilled! And I’m honoured and delighted, too, that I am to be included in an upcoming Strong Museum exhibition of women who created a toy or game that became a classic. It’s very exciting.

The National Toy Hall of Fame at The Strong Musuem, was established in 1998 and recognizes toys that have inspired creative play and enjoyed popularity over a sustained period. Each year, the prestigious hall inducts new honorees and showcases both new and historic versions of classic toys beloved by generations. Final selections are made on the advice of historians, educators, and other individuals who exemplify learning, creativity, and discovery through their lives and careers. Toys are celebrated year-round in an exhibit at The Strong museum in Rochester, New York.

For more information about the hall, visit toyhalloffame.org.