Features

Dr Toby Young, Gianturco Junior Research Fellow at Linacre College, writes for Arts Blog about the Displaced Voices project. Read the previous blog post on Displaced Voices here.

Displaced Voices is an initiative that brings together school and university students with the professional musicians of the Orchestra of St John’s, community members, refugees and asylum seekers through musical collaboration, and raises awareness about refugee issues in Oxfordshire through the medium of artistic expression. Together with conductor, researcher and activist Dr Cayenna Ponchione, I have been working over the past term with four creative, intelligent and emotionally mature refugee students from the Oxford Spires Academy to help give voice to their lived experiences of forced migration.

Through the creation of live orchestral ‘backing tracks’ to underscore spoken word performance of their own poetry – developed as part of an award-winning poetry programme developed by Kate Clanchy – we have been exploring how music might help magnify the strong emotional content of these unique and moving stories, creating a musical experience somewhere akin to the accompaniment of a rousing or emotional speech in film music. As well as offering technical and aesthetic discussions of the ways in which music can support, enhance or even subvert spoken text, our group sessions have involved a certain amount of discussion about the student’s experiences. Even reflecting on these stories now, months after first hearing their shocking accounts of living in brutally war-torn countries and undergoing distressing journeys to seek protection in the UK, gives me chills.

Dr Toby Young and Dr Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey with students from Oxford Spires Academy.

Dr Toby Young and Dr Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey with students from Oxford Spires Academy.As well as a direct collaboration on the students' spoken performances, I have been writing my own setting of one of the student’s poems to be sung by the mezzo-soprano Charlotte Tetley. Compared to my other experiences of working with text (by both historical and living writers) this process has thrown up a lot more challenges: for example, techniques and methods I might have used to engage with to texts in the past – perhaps by trying to empathise with the text through connection to my own lived experiences (in this case my homesickness or experience of injustices), or by trying to think of the poem as a sort of atmospheric backdrop to key words or phrases – feel unethical and unfair. These stories are hugely personal and poignant to the students, with every word being critical for an authentic and unfiltered representation of their stories in specifically the way they need to be told. In contrast to historical texts where adding my own meaning, experience and ownership to a text is taken for granted, my role here is of translator, not re-interpreter.

Running alongside the creative component of Displaced Voices is a research project that seeks to methodically and critically understand the impact of these activities and concerts on not only the students, but also other individuals who might come into contact with the music (for example the orchestral musicians, teachers, audiences and so on). As well as trying to evaluate how effectively students feel that the music has enhanced or detracted from the emotional meaning of their poems, we are interested in understanding how the whole process – both the challenges and rewards – might impact on the students’ lives. Watching the students’ develop into confident and talented young public speakers has been truly inspirational, and seeing how music has afforded them an increased confidence in their stories and identities has been deeply moving. Through this and future projects, it is our hope that we are able to help support the development of these unique young people as future leaders and agents of social change, amplifying their powerful stories to new parts of society so that their experiences might help those in power to better consider how they might support the cultural integration and wellbeing of young migrant children all over the country.

To date no research has been conducted on an orchestral engagement project like this one, and it is our hope that the findings of this study will inspire and inform other orchestras to create similar projects. I cannot emphasise enough how strongly I recommend other organisations consider using the methods we have piloted here to engage with refugee and migrant communities near them. It has been one of the most inspiring, moving and valuable experiences of my life, and I leave the process a transformed musician and human being.

Displaced Voices will be performed in Somerville Chapel, Oxford on 18 January, preceded by a panel discussion exploring the issues facing refugees in the UK and a showcase of poetry on the subject of displacement, migration and home. For further information, and to book, click here.

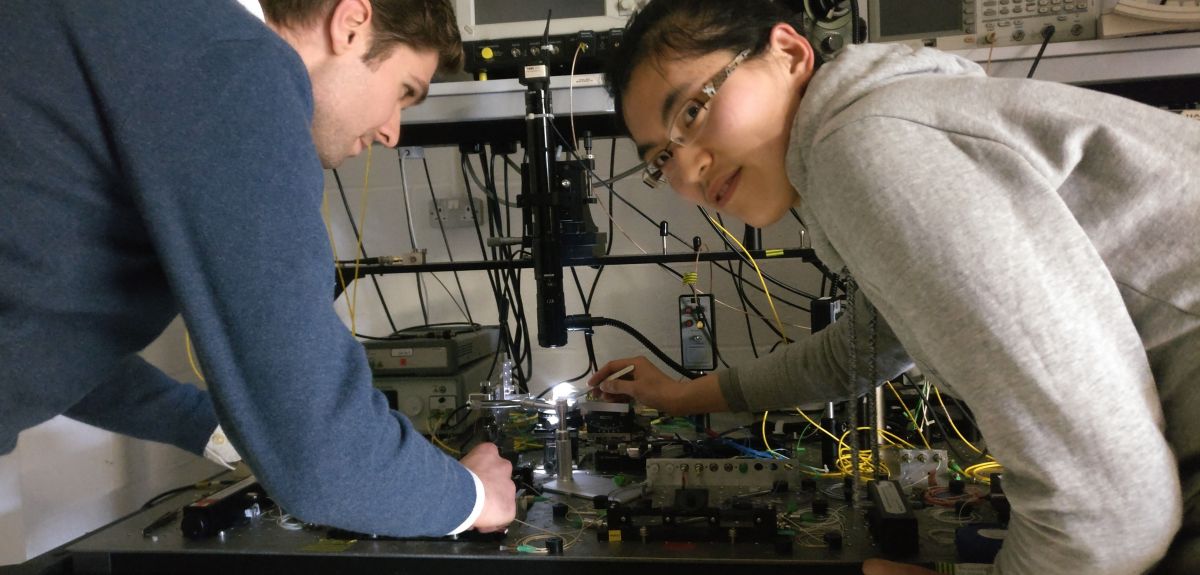

A new device could enable computers that use optics and electrical signals to interact with data

Researchers from the universities of Oxford, Exeter and Münster have demonstrated a new technique that can store more optical data in a smaller space than was previously possible on-chip. This technique improves upon the phase-change optical memory cell, which uses light to write and read data, and could offer a faster, more power-efficient form of memory for computers.

In Optica, The Optical Society's journal for high impact research, the scientists describe their new technique for all-optical data storage, which could help meet the growing need for more computer data storage.

Rather than using electrical signals to store data in one of two states - a zero or one - like today’s computers, the optical memory cell uses light to store information. The researchers demonstrated optical memory with more than 32 states, or levels, the equivalent of 5 bits. This is an important step toward an all-optical computer, a long-term goal of many research groups in this field.

Research team leader Harish Bhaskaran from Oxford University’s Department of Materials said: ‘Optical fibres bring light-encoded data to our homes and offices, but that information is transformed to electronic signals once inside computers. By bringing the speed of light-based data transmission to the circuit boards that run computers, our all-optical memory could enable a hybrid computer chip that interacts with data both optically and electrically.’

The new work is part of a large project called Fun-COMP, for Functionally-scaled Computing technology, that brings academic and industrial partners together to develop groundbreaking hardware technologies.

Writing data with light

optica detail

optica detail

The optical memory cell uses light to encode information in a phase change material, a class of materials used to make re-writable CDs and DVDs. A laser heats portions of a phase change material, which causes it to switch between states where all the atoms are ordered or disordered. Because these two states exhibit different optical indices of refraction, the data can be read using light.

Phase change materials can store data for a long time because they remain in the disordered or ordered state until illuminated again with the specific type of laser light originally used to write the data. Mixing different ratios of ordered and disordered states in an area of the material allows information to be stored in a continuum of levels instead of just a zero and a one as in traditional electronic memory.

The researchers accomplished the increased resolution by using a new technique they developed that uses laser light with a single, double-stepped pulse — two pulses put together into a rectangular-shaped pulse — to precisely control the melting and the crystallisation of the material.

Multi-level memory storage

The researchers showed that they could use their approach to reliably encode data on 34 levels, which is more than the 32 levels necessary to achieve 5-bit programming.

‘This accomplishment required understanding the interaction between the light and the material perfectly and then sending exactly the right sort of laser pulse necessary to achieve each level,’ said Bhaskaran. ‘We solved an extraordinarily difficult problem.’

The new technique could help overcome one of the bottlenecks limiting the speed of today’s computers: the link between the processor and the memory. ‘A lot of work has gone into improving the communication between these two units using fiber optics,’ said Bhaskaran. ‘However, linking these two units optically still requires expensive electro-optical conversions at both ends. Our memory cell could be used in a hybrid optical-electrical setup to eliminate the need for that conversion on the memory side by allowing data to be stored and retrieved optically.’

Next the researchers want to integrate multiple memory cells and individually program them, which would be required to make a working memory chip for a computer. The research groups have been working closely with Oxford University Innovation, the University’s innovation arm, to develop commercial opportunities arising from their research on photonic memory cells. The researchers say that they can already replicate the devices extremely well but will need to develop light signal processing techniques to integrate multiple optical memory cells.

'What are you going to do with a degree in Classics / English / Maths?' is a common question, often from parents, and particularly when compared with apparently more vocational degree subjects. The question becomes particularly loaded when the prospective student is from a non-traditional background, and perhaps is the first in their family to consider going to university.

Analysis of the first career destinations of the Oxford undergraduates who left in 2017, shows that there is no statistically significant difference in career outcome associated with any of seven different measures of social background. This result is contrary to the national picture; it also confirms the result that we found for the Oxford leavers of 2015.

By career outcome, we used three measures: the proportion of students unemployed and looking for work, the proportion in a 'graduate-level' job, and the average starting salary. While there are, of course, other measures of career success, including satisfaction, happiness, feeling of doing something worthwhile, and intellectual challenge, all of these are difficult to quantify – so we use what is widely and reasonably reliably available. The career measure is taken from the Destination of Leavers from Higher Education (DLHE) survey of all leavers, six months after leaving. Again, we all recognise that higher education can equip graduates with life skills – and surveying five, 10 or 20 years later would be more helpful. As an aside, the DLHE is now changing to a Graduate Outcomes Survey, taken 15 months after leaving.

By social background, we used seven measures: two post code assessments (ACORN, a postcode-based tool that categorises the UK's population by level of socio-economic advantage; and POLAR, a similar tool that measures how likely young people are to participate in higher education based on where they live); ethnic background (black and minority ethnicity (BME) and white); school type (state and independent), Oxford's 'Widening Participation' (WP) flag (which is used to determine students who are from disadvantaged backgrounds); Oxford bursary holders; and household income (£0-£16,000, £16,000-£25,000 etc.).

Effectively we found no association between social background and initial outcome. While there are some differences in starting salary for some groups (for example, a higher proportion of BME students than of white students, start work in higher paying sectors such as banking and consulting), once the analysis controls for the industry sectors each group enter, that difference is not significant.We analysed whether there was any statistically significant difference in the three outcome measures (unemployment, graduate-level work, average salary) for the different populations of students on all seven measures. For example, BME versus white students, state versus independent school students, WP-flag versus non-WP-flag students, and so on. We ran the analysis for the whole University of Oxford and for each division (Medical Sciences; Maths, Physical & Life Sciences; Social Sciences; and Humanities) separately.

In particular, it's worth noting that there is no difference in outcome for students from households with incomes below £16,000 per year versus everyone else.

This is a very welcome and reassuring result of which Oxford can be rightly proud. The University can confidently tell all prospective students, regardless of their school type, ethnic group, postcode, or household income, that their career prospects are not significantly affected by their background.

At Oxford, the answer to the opening question, 'What are you going to do with a degree in Classics / English / Maths?' is 'almost anything.'

Jonathan Black is the director of Oxford University's Careers Service.

How could a sugar pill placebo cause harm? A new review of data from 250,726 trial participants has found that 1 in 20 people who took placebos in trials dropped out because of serious adverse events (side effects). Almost half of the participants reported less serious adverse events. The adverse events ranged from abdominal pain and anorexia to burning, chest pain, fatigue, and even death.

The study found that the apparently strange phenomena of sugar pills producing harm can be explained by misattribution and negative expectations.

Misattribution

Someone in a trial might have a symptom like a stomachache for any number of reasons that are not related to the trial. Because they are in a trial, they think the trial intervention caused the ache. This gets reported as an adverse event when it would have happened anyway.

Negative expectations

The way patients are warned about adverse events can sometimes cause an adverse event. Effects of negative expectations are called ‘nocebo’ (‘negative placebo’) effects. ‘Our study provided preliminary data indicating that some trial participants experience nocebo effects,’ reports lead author Jeremy Howick. Other studies provide more definitive evidence that the way patients are warned about adverse events can affect whether they report them. For example, a study found that patients in a randomised trial of aspirin or sulfinpyrazone for treating unstable angina who were warned about gastrointestinal adverse events were six times more likely to withdraw from the study due to reported gastrointestinal adverse events. A more recent study published last year in The Lancet found that patients were more likely to report adverse events when they knew they were taking statins, compared to when they didn’t. This is probably because the belief that statins cause adverse events like muscle pain can actually produce the muscle pain.

Finding ways to reduce adverse events among patients in placebo groups is important for improving trial quality (since fewer participants will drop out), and improving trial ethics (by avoiding harm). The question is: how?

‘Misattribution can be hard to avoid,’ says Jeremy Howick, ‘because it’s hard for someone to know whether a symptom like a stomachache would have occurred anyways or whether it was because of the trial. However, I believe we can reduce the harm caused by negative expectations.’

For example, telling patients that a new treatment is safe for 90% of patients contains the same information as saying it causes adverse events like headaches in 10% of patients. But the second way may be more likely to actually cause the adverse events than the first.

Unfortunately, guidance for informing trial participants about trial intervention harms, in a way that is ethical, understandable, and does not produce nocebo effects, is currently under-researched. A recent study suggested that information provided to trial participants often fails to tell them what they wish to know, and that it is presented in a way that is difficult to understand. Ongoing research at the Universities of Oxford and Cardiff is looking at ways to inform patients in trials about the best way to provide balanced information about the benefits and harms of participating in trials. Their preliminary research suggests that patients are provided more information about trial harms than trial benefits.

Says co-author Professor Kerry Hood (Director of Cardiff Centre for Trials Research): ‘We believe it is possible to balance the information about trial benefits and harms in a way that is fact-based and that does not cause unnecessary harm. This can be achieved by ensuring that the benefits, as well as the harms, are explained in a way patients understand.’

The full paper, 'Rapid Overview of Systematic Reviews of Nocebo Effects Reported by Patients Taking Placebos in Clinical Trials,' can be read in Trials.

A UK instrument, co-designed by the University of Oxford, has captured the first sounds ever recorded directly from Mars.

The NASA InSight lander, which is supported by the UK Space Agency, has recorded a haunting, low rumble caused by vibrations from the wind. These vibrations were detected by an ultra-sensitive seismometer, developed in the UK, and an air pressure sensor sitting on the lander's deck.

Both recorded the Martian wind in different ways. The seismometer recorded vibrations as the wind moved over the lander's solar panels, each of which is more than 2 metres in diameter and sticks out from the sides of the lander like a giant pair of ears. The air pressure sensor recorded the vibrations directly from changes in the air.

This is the only time during the mission that the seismometer - called the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure, or SEIS - is capable of detecting these sounds. In a few weeks, it is due to be placed on the Martian surface by InSight's robotic arm. For now, it is recording wind data that scientists will later be able to cancel out of data from the surface, allowing them to separate "noise" from actual Marsquakes.

These sensors can detect motion at sub-atomic scales, including the wind on Mars, which is barely within the lower range of human hearing.

Dr Neil Bowles, from the University of Oxford’s Department of Physics, said:

'To get the first data from the seismometer instrument package has been fantastic and even with a short test run the analysis is now full swing. To "hear" the low frequency rumble of the Martian wind on the lander being picked up by the SEIS-SP is really eerie and provides a strangely human connection to this very different environment.'

- ‹ previous

- 61 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?