Features

Professor Rosalind Thomas, Balliol College.

COVID-19 has prompted reflection on many previous pandemics, above all the outbreaks of plague in the 17th century and the Black Death in the 14th. I want to go still further back to the great plague of Athens in the fifth century B.C., which hit the Athenians shortly after they began the great Peloponnesian War against Sparta and her allies in 431 B.C.

The Athenian plague prompted the historian Thucydides to offer in his History a full medical and secular description, so that if it occurred again, people ‘would not fail to recognise it’, as he cautiously put it. Thucydides also offered a brilliant and searing analysis of the plague’s social and mental effects, a devastation of the social order which has been noted after other pandemics. As a survivor himself, he offered as his own observation that survivors acquired immunity, the first attested (written) observation of this phenomenon. This was an absolutely catastrophic plague with a massive death-toll; the precise disease is not clearly identifiable. Can we learn anything from his account?

The death rate was far higher, of course, than our current pandemic: of the 4,000 Athenian soldiers who sailed to northern Greece, 1,050 were lost in 40 days

The ‘Athenian plague’ was not only Athenian, though we have the account of its impact only for Athens. It also hit Egypt and much of the Persian King’s territory, according to Thucydides, and it came to Athens via the Piraeus, and to the northern Aegean. The death rate was far higher, of course, than our current pandemic: of the 4,000 Athenian soldiers who sailed to northern Greece, 1,050 were lost in 40 days.

Thucydides tells of the symptoms of high fever, inflammation, sneezing, retching and spasms, and unbearable thirst, with people throwing themselves into rain-tanks, others recovering but losing extremities and even their sight or memory. He describes the dying gathering around wells, and piles of the dead lying in the streets and even in the temples. Thucydides spoke from personal experience.

There are aspects of the Athenian plague which touch our own current experience, and others which Thucydides as a student of human nature meant future generations to ponder – and to look out for again. First, there was no cure: what worked for some failed for others, and the doctors could not help.

Thucydides refers somewhat acidly to the treatment by regimen (diet etc.) which was the new Hippocratic method of the time: it had no effect and doctors died even more frequently than their patients. Second, it was made worse by the crowded conditions in Athens and in ‘the most populous places’, as Thucydides carefully pointed out.

The leading statesman Pericles had persuaded the Athenians at the outbreak of war to evacuate the countryside to within the walls of Athens, and not venture out to fight the invading army; ironically, his determination on war with Sparta but not engaging on land made the plague more destructive. Moreover, it was entirely unexpected. Even Pericles, praised for wisdom and forethought, could not foresee it, and he urged on the Athenians their hard-line stance to protect the Athenian empire, at the very height of their confidence. The plague was no respecter of persons – rich and poor died. Pericles himself died. The hoplite soldiers (fairly well-off) died and infected others. Thucydides was careful to make clear, against Hippocratic medical theory, that this was infection and had little to do with one’s way of life, medical care, or humours; nor was it affected by religious remedies.

There are aspects of the Athenian plague which touch our own current experience...First, there was no cure: what worked for some failed for others, and the doctors could not help

Thucydides offered an entirely secular vision of the plague. Its cause was terrifyingly unknown: he would leave speculation as to its causes to others, ‘if causes can be found adequate for such an upheaval’. Its nature was ‘beyond logos’ (beyond description or understanding). Many Greeks, however, would have believed that it was the god Apollo who sent the plague as punishment, and by offering a full-scale scientific description of symptoms and the course of the disease, as in the new Hippocratic methods of objective observation, Thucydides was saying that it was amenable to human enquiry and observation, and the new science of medicine (he says there was no cure, but perhaps one might hope for one eventually). His emphasis was on this detailed description, and on the social and moral effects.

Thucydides offered an entirely secular vision of the plague. Its cause was terrifyingly unknown...‘if causes can be found adequate for such an upheaval’. Its nature was ‘beyond logos’ (beyond description or understanding).

For he stresses first that the most dangerous element was the despair or dejection (athumia) which hit whenever someone felt themselves sickening, weakening their power of resistance. He stresses that those who tried to nurse the sick fell ill themselves, while those left alone died of neglect.

Thucydides then traces the corrosion of the social order and moral values as people abandoned the proper formalities of burial. There was the onset of ‘anomia’, literally ‘lawlessness’ or unconcern for customs and tradition. This passage has had deep influence on later plague descriptions: ‘men dared to do what formally they had done in secret’, seeing the same disaster hitting all alike, ‘those of good fortune dying suddenly and those with nothing taking their possessions’.

Bodies and possessions were alike ephemeral and so men turned to enjoyment: ‘neither fear of the gods nor human law held people back’, no one feared eventual coming to justice, for they would probably not live to see it. And so in this darkest of passages, Thucydides re-calibrates contemporary debates about the nature of religious belief and the purpose of punishment to trace the beginnings of the decline of social order.

In this darkest of passages, Thucydides re-calibrates contemporary debates about the nature of religious belief and the purpose of punishment to trace the beginnings of the decline of social order

It should be stressed how remarkably original this analysis was at the time: no writer had tried to analyse the collapse of social norms in this way. It is such an uncompromising picture that some scholars have thought it must be a little exaggerated, but that denies the value of the astute eye-witness. We recall that this occurred at the height of Athenian prosperity and confidence: the era of the Acropolis temples and the intellectual ferment visible in Athenian tragedy, comedy, philosophy and the radical democracy. Not everything collapsed, though there was an immediate effect of acute demoralisation, while longer-term effects might be harder to calibrate - what Thucydides saw as a long-term malaise and loss of integrity.

The contrast with our own experience is stark. The Coronavirus has brought out a vast reservoir of individual sacrifice for others, mutual respect and responsibility for the greater good (some, no doubt, taking advantage also). But two points stand out. Even in Thucydides’ dark description, there was humanity: he does say that the doctors tried to tend the sick (only they died too – as now); he does say that friends and family tried to look after each other (only they died). Indeed in a ray of hope, he explains that people were best tended and cheered by those who had the plague and survived, for they ‘knew in advance’ and were unafraid, and indeed the survivors entertained the ‘empty hope’ that they would never again fall ill. So there were numerous self-sacrificing and pitying helpers and they were only brought low by the disease itself. He hints perhaps that at least if you know in advance, it might not be so unbearable next time.

There was no state response, no health system, no public health knowledge or policy: the Athenian democracy was sophisticated, but on the matter of the plague, this was a do-it-yourself...response

And finally, there was no state response, no health system, no public health knowledge or policy: the Athenian democracy was sophisticated, but on the matter of the plague, this was a do-it-yourself, entirely private response. As far as we know, the only public, official response on the part of the Athenians was to purify the sacred island of Delos and introduce the cult of the healing god Asclepius.

It was through close observation that Thucydides deduced the operation of what we call ‘acquired immunity’

It was through close observation that Thucydides deduced the operation of what we call ‘acquired immunity’, and he was surely offering a rival theory to the nascent science of medicine around Hippocrates.

The other lasting lesson from this historian who wished readers to interpret the future by means of an accurate knowledge of the past, was about human nature: the reactions of human beings in the face of catastrophe and inexplicable death, and the wider effects on social values, morality and the scaffolding of justice. He was careful to say later that war itself also had corrosive effects, but that was humanly contrived and in some respect avoidable; the plague was completely unexpected and a force of nature. So in the end he teaches us to expect profound changes on the level of individuals’ reactions and wider social values in the face of huge upheaval; and on the state level to expect the unexpected – and hope for good government when it hits. The Athenians continued the war anyway.

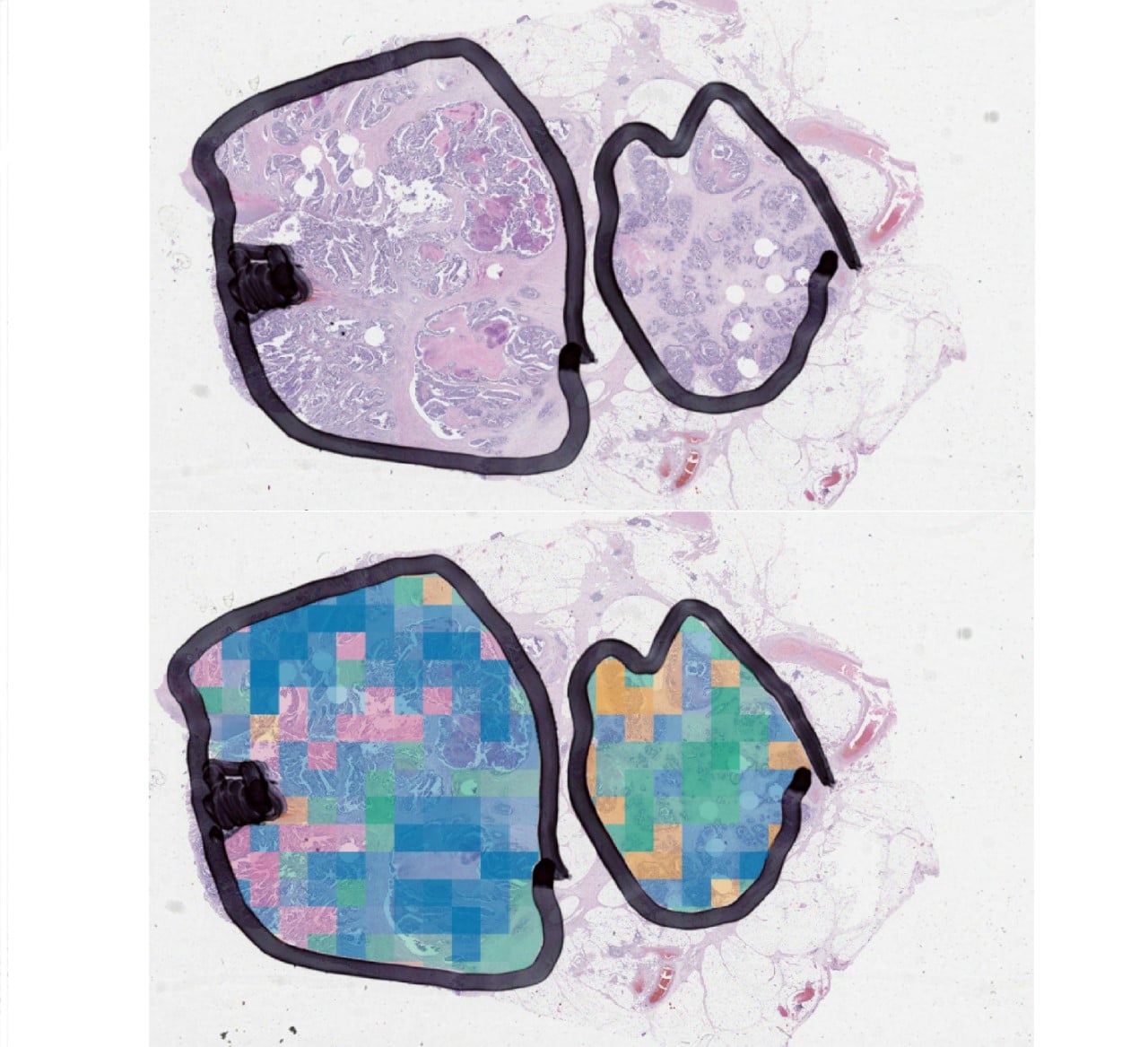

A new study from S:CORT demonstrates an easy, cheap way to determine colorectal cancer molecular subtype using AI deep-learning digital pathology technology.

Understanding the molecular subtype of a cancer is becoming an importance part of the diagnostic process as it helps a doctor better understand a patient’s prognosis, determine the best course of action for treatment and helps researchers devise new, more-efficient, precision therapies.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) currently has four known molecular subtypes which are identified on the basis of its RNA expression profile, using RNA analysis. But the process of RNA analysis is costly, technically challenging and it requires a specialist to interpret data to determine the subtype. In order to more efficiently and cheaply determine the molecular subtype of a patient’s CRC, there is a need to use more easily-acquired data on a tumour and categorise its subtype based on an automated technique.

One prevalent source of data in cancer diagnostics is images, such as histological images of the microscopic anatomy of a cancer. Almost all CRC patients already have a sample of their tumour inspected by a pathologist as part of their standard care.

Caption: Image information can be used to predict the molecular classification of patient tumor samples in colour, using state-of-the-art deep learning models in pathology.

A new paper published by Dr Korsuk Sirinukunwattana, Dr Enric Domingo, Prof Viktor H Koelzer & Prof Jens Rittscher from the Stratification in Colorectal Cancer consortium (S:CORT), has demonstrated the potential for using these images to determine molecular subtype.

Through the training of a deep-learning neural network, using over 1,000 tumour samples, the team discovered that AI could be trained to distinguish between the four molecular subtypes using images alone.

Usually, histological images are a modest indicator of how colorectal cancers have progressed, and there is currently no way to determine the molecular subtype of a tumour by the human eye alone, without doing a gene profile on tumour samples. However, this new study demonstrates that technology can be trained to identify the minute morpho-molecular differences between molecular subtypes.

This new concept, called Image-based Consensus Molecular Subtyping (imCMS), will allow images to be interpreted through association of tile-level predictions with morphology, molecular features and outcome data.

Furthermore, this study also demonstrated that AI is able to classify the molecular subtype of samples that were previously unclassifiable by the standard process of RNA expression profiling. It also provides information for the spatial distribution of each subtype within a tumour.

This AI technology will have huge implications on the standardisation of classifying molecular subtypes of CRC. It opens new opportunities to create simple, cheap and reliable ways to quickly stratify a patient’s colorectal cancer, and decreases the demand for specialist input that is not always immediately available.

It has potential to reveal new avenues for the translation of the classification of CRC subtypes into clinical practice and increase availability of molecular stratification in low-resource settings, helping to make accurate cancer diagnoses and appropriate treatment more accessible to everyone.

About S:CORT and the researchers

For more information about the Stratification in Colorectal Cancer consortium (S:CORT) see here.

Samples for this study were collected by the S:CORT program and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The S:CORT consortium is a Medical Research Council stratified medicine consortium jointly funded by the MRC and CRUK. This work was further supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

This study is a joint venture conceived by Prof Tim Maughan (Dept. of Oncology), Prof Ian Tomlinson (Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, Edinburgh), Prof Jens Rittscher (Institute of Biomedical Engineering) and Prof Viktor H Koelzer (University Hospital and University of Zurich; Honorary Senior Clinical Researcher, Dept. of Oncology, University of Oxford;)

S:CORT consists of a team of clinicians, healthcare professionals, academics and scientists across the UK, lead from Oxford by Prof. Tim Maughan, and seeks to apply cutting edge molecular diagnostic and histopathological technologies to improve and tailor the treatment of colorectal cancer patients.

By Dr Michelle Kendall, senior researcher, Oxford University’s Nuffield Department of Medicine

A Test and Trace (TT) programme was rolled out across the UK in May 2020, first on the Isle of Wight (5 May) and then nationwide (18-28 May). The Isle of Wight’s programme included version 1 of the NHS contact tracing app. We looked to see if the Isle of Wight’s epidemic changed after the TT launch and if the island fared any differently from comparable areas of the UK.

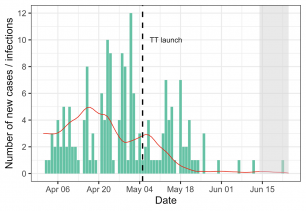

Using Public Health England’s daily “case counts” (positive swabs) we developed a method to estimate the number of new infections per day - there is a lag because people rarely get swabbed the day they are infected. The graph below shows Pillar 1 (hospital testing) case counts on the Isle of Wight in green, and our estimated number of new infections per day in red. New infections were decreasing from mid-April. There was a slight increase at the end of April, possibly an artefact of increased testing on 5th May, but then a noticeable decrease in infections despite the increased testing shortly after the TT launch.

Figure 1. Isle of Wight Pillar 1 data used to back-calculate estimation of incidence of new infections (red) from COVID-19 case data (green)

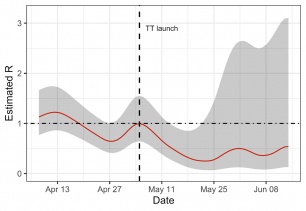

Similarly, the reproduction number R - the average number of further infections each infected person causes - decreased rapidly on the island following the TT launch as shown by the red line below:

Figure 2. Isle of Wight Pillar 1 data (red line) used to estimate R, together with confidence intervals (grey shade)

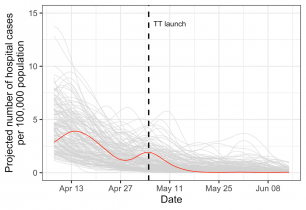

But how did the Isle of Wight compare to other areas? We used a variety of methods which all led to the same conclusion: something quite different happened on the Isle of Wight. The incidence and R rate dropped more rapidly than for other areas over comparable time periods. The graph below is a “nowcast” of the expected number of new hospital cases in the near future. The island had a sizeable epidemic in April-May, positioned “middle of the pack” in comparison with other areas; by June-July it led the way with case counts down to less than one a week, even when we included Pillar 2 (community tested) cases. Using a Maximum-Likelihood method we found that from March-May the Isle of Wight was ranked amongst the worst R rates in England (147th out of 150) but by mid-June it was positioned 10th best.

Figure 3. Pillar 1 data showing a simple "nowcast" for 150 local authorities to quantify the combined effects of R and incidence; the Isle of White shown in red

We have made our analyses available in this interactive EpiNow-C19 tool which updates daily. It allows you to view the epidemic trend in each of the 150 local authorities to identify successes and hotspots, including the most recent surges in Leicester, Herefordshire and Blackburn with Darwen.

The success on the Isle of Wight is striking, and the course of its epidemic was different from other areas - a statistically significant difference. To prove that the TT programme was the cause of the success would require ruling out all other possible causes, for which we would need more data. The island’s epidemic control certainly warrants further investigation because it might translate to other local and national strategies.

If TT did have an impact we will also need to disentangle which aspects had the greatest effect. Was it the huge advertising campaign at the launch? Did people self-isolate more carefully after a positive test result? Was the contact tracing programme getting ahead of the virus, advising people to quarantine before they infected others? And if so, was that primarily human contact tracing or via the app? Top level results suggest 163 people were traced through the human tracing service and 1,188 through the app between 6-26th May. A key piece of the puzzle would be: of the people who tested positive, how many were already self-isolating because they had been contact-traced? We hope that more data will soon be made available so that we can answer these important questions.

COVID-19 incidence and R decreased on the Isle of Wight after the launch of the Test and Trace programme. Kendall et al. Available as a preview ahead of pre-publication on MedRxiv.

Face coverings in shops will be made compulsory from 24 July, and the prohibition may be extended to other indoor spaces. The move follows last week’s COVID-19 face coverings study from Oxford’s Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science on behalf of the Royal Society and British Academy.

The announcement was made this morning, and comes after Prime Minister Boris Johnson was pictured over the weekend publicly wearing a face covering. The Prime Minister described face coverings yesterday as offering a ‘great deal of value’ in controlling the spread of the coronavirus and giving people confidence to go back to shops and workplaces. But this morning came the news that, from 24 July, shoppers face a £100 fine, if they enter a shop without a face covering.

There is a general assumption that countries such as the UK, which have no culture or history of mask wearing, will not rapidly adopt them or that people will be put off going to shops if they have to wear a face covering. But this just doesn’t reflect the data from similar countries

Professor Melinda Mills, Director of the Leverhulme Centre and lead author of the study on the effectiveness of face coverings, says, ‘It is great news that face coverings are to be made compulsory in shops in England. More than 120 countries around the world have introduced recommendations or regulations and the report last week contains clear evidence that face coverings are effective in respect of COVID-19.’

She maintains, ‘There is a general assumption that countries such as the UK, which have no culture or history of mask wearing, will not rapidly adopt them or that people will be put off going to shops if they have to wear a face covering. But this just doesn’t reflect the data from similar countries. As of late April, mask-wearing was up to 84% in Italy, 66% in the US and 64% in Spain, which by June was over 90%, increasing almost immediately after clear policy recommendations and advice was given to the public.’

As early as April, a report in the British Medical Journal was advising people to wear face coverings. Professor Trisha Greenhalgh, Oxford’s professor of primary health care sciences, was among experts who urged the adoption of face coverings, 'It’s time to encourage people to wear face masks as a precautionary measure on the grounds that we have little to lose and potentially something to gain.'

They maintained in their report that, despite limited evidence, masks ‘could have a substantial impact on transmission with a relatively small impact on social and economic life’.

Face coverings have not been widely worn in the UK, in spite of the pandemic. The Leverhulme-led study shows cloth face coverings, even homemade masks of the correct material, are effective in reducing the spread of the virus – both for the wearer and those around them

Speaking today about the announcement, Professor Greenhalgh says, 'I very much welcome this news. It made no sense to mandate face coverings on public transport while not requiring them in other crowded and poorly-ventilated indoor spaces such as shops and supermarkets. What we now urgently need is proactive use of behavioural science techniques to inform a public information campaign to overcome weeks of mixed messages and shift the ethos of this policy from something that is 'enforced' and 'policed' to an exercise in common sense and social solidarity. Masking is a symbolic practice as well as a public health intervention. My own team and also Melinda Mills in Demography (among many others) have done research on this topic; we’d be happy to help make this policy a success.'

Face coverings have not been widely worn in the UK, in spite of the pandemic. The Leverhulme-led study shows cloth face coverings, even homemade masks of the correct material, are effective in reducing the spread of the virus – both for the wearer and those around them. And the study reveals that, once the WHO announced there was a pandemic in mid-March, within days many countries around the world had already recommended wearing face masks. Nations including South Korea, Japan and a series of African countries, experienced in handling previous epidemics including SARs and Ebola, have experienced very low numbers of deaths and transmission.

It is ‘far more invasive’ to tell people to stay at home than to wear a mask

Professor Mills, insists that face coverings should be recognised as a public health issue as part of a package of policies alongside hand hygiene and social distancing, not a matter of civil liberties.

She maintains, it is ‘far more invasive’ to tell people to stay at home than to wear a mask, with the report revealing that in order to increase compliance of the general public, it is important that they understand how the virus and coverings works to protect both themselves and others. The study reveals, ‘Next to hand washing and social distancing, face masks and coverings are one of the most of widely adopted non-pharmaceutical interventions for reducing the transmission of respiratory infections.’

Refuting claims that there is no or weak scientific evidence, Professor Mills finds that there has been an over-reliance on medical studies and specifically ‘randomised control trials’ – while high quality behavioural studies have been discounted. But she says, ‘The evidence is clear that people should wear face coverings to reduce virus transmission and protect themselves, with most countries recommending long ago that the public should wear them, particularly in enclosed indoor spaces and crowded areas.’

The evidence is clear that people should wear face coverings to reduce virus transmission and protect themselves, with most countries recommending long ago that the public should wear them, particularly in enclosed indoor spaces and crowded areas

The study calls for clear and consistent policies and public messaging on the wearing face masks and coverings by the general public. Professor Mills says, ‘The public is confused about wearing face coverings because they have heard the scientific evidence is inconclusive and advice from the WHO and others has changed.

‘But where are randomised control trials about coughing into your elbow or social distancing?’ And she adds ‘People need to know what to wear, when and where to wear it, how to wear it and who cannot wear it.’

Professor Mills says, ‘What to wear is high quality multi-layer cloth coverings and not surgical masks or respirators and people need to ensure there are no gaps. For instance, combining cotton and silk or flannel provide over 95% filtration, so wearing a mask can protect others.

The public is confused about wearing face coverings because they have heard the scientific evidence is inconclusive...But where are randomised control trials about coughing into your elbow or social distancing?

‘When and where includes crowded shops, where you cannot often keep social distance, are places where face coverings would be valuable, but you don’t need to wear one while outside, walking or jogging, in a socially distanced way. And in restaurants, you need to wear one, until you are sitting down at your table. We also need to acknowledge who cannot wear them such as those with disabilities, breathing difficulties or young children.

Just as the WHO gathered evidence and changed its advice in early June, it is now time to re-evaluate the evidence and make clear recommendations to the public and those who need to re-open their businesses

'By learning from mask-wearing experiences from previous epidemics, such as SARS, H1N1 and MERS, the systematic review revealed key behavioural factors underpinning the public’s compliance to wearing a mask. People need to understand virus transmission and how masks protect them and others. And they need to understand how to reduce the barriers of wearing them related to practical aspects such as comfort or what to do in a restaurant or shop.’

She says, ‘We learned from previous pandemics that individuals underestimate their own risks of contracting the virus or transmitting it to others and think that ‘it won’t happen to me’.’

But, she adds, ‘Just as the WHO gathered evidence and changed its advice in early June, it is now time to re-evaluate the evidence and make clear recommendations to the public and those who need to re-open their businesses.’

The full text of ‘Face masks and coverings for the general public: Behavioural knowledge, effectiveness of cloth coverings and public messaging’, on behalf of the Royal Society and British Academy can be found here.

See also

COVID Conversations

Face masks work!

Join Professor Melinda Mills to hear more about the effectiveness of different face mask types and coverings and ask any questions you have.

Wednesday 22 July, 1.15pm–1.45pm

This talk will be broadcast here on YouTube, and on our main Facebook & Twitter channels.

By Jesús Aguirre Gutiérrez, researcher at the Environmental Change Institute, School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, and the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre, The Netherlands.

The tropical forest canopy is one of the Earth’s underexplored frontiers. To understand how these unique environments respond to climate change a team from the Ecosystems Lab at the University of Oxford and partner institutes in Ghana gathered evidence from the treetops, finding drier forests are at greater risks.

Our natural world is facing unprecedented changes in the distribution of biodiversity – the variety of life on earth – at local and global scales. Around one million species are threatened with extinction, posing an imminent threat to the functioning of ecosystems and to human wellbeing.

Image: A tree climber collecting leaf samples 30 m up a rainforest tree (Ankasa, Ghana). © Yadvinder Malhi.

In our new study, recently published in Nature Communications, we investigate if and how climate change has affected the diversity of tropical ecosystems in West Africa over the last decades. In particular, we wanted to understand if wetter and drier tropical forests responded in different ways to the same drivers of change.

For this study we conducted fieldwork in Ghana over six months. The field campaign was led by Dr Imma Oliveras and Dr Stephen Adu Bredu and coordinated by co-authors Theresa Peprah and Agne Gvozdevaite. It formed part of a global effort. More than 25 research assistants from KNUST University and Forestry Institute of Ghana (FORIG) participated in the field campaign and were trained in the sampling techniques and scientific protocols for undertaking the research.

Image: Albert Aryee labels plastic bags for collecting samples of leaves. All bags must be labelled with a unique code so that each leaf can be tracked to a branch, tree, and site. © Imma Oliveras

During the campaign we visited clusters of sample plots at three sites, stretching along a climate gradient from humid ancient rainforest through to parched try forest and savanna. We sampled leaves and branches from 299 trees. These were very long days, usually starting at 4.30 am with a group breakfast and by 6 am we would be already working in the field. We would finish the fieldwork at around 3 pm and then work in the field laboratories until 10 pm. Some of the research assistants – who were masters and undergraduate students at the time – have pursued further postgraduate studies after the experience and successfully found scholarships in Ghana, Europe and the US.

Image: Working in the field laboratory. © Imma Oliveras

Image: Working in the field laboratory. © Imma Oliveras

When starting this research, we expected that a drying trend would be reflected in overall diversity decreases for all tropical forests. However, we found that forest communities in drier sites experienced on average stronger declines in functional, taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity across time than forest communities in wetter areas.

This means that drier forests are transitioning towards increasingly more homogenous forest communities, diverging further from wetter forests in functional, taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity. In contrast, wetter forests showed on average increases in functional and taxonomic diversity, which could be the result of their higher atmospheric and ground water availability in comparison to that available for drier forests. Overall, climatic and soil conditions partly explained the changes in diversity and differences in responses between drier and wetter tropical forests in West African.

Stephen Adu-Bredu and Theresa Peprah from CSIR-Forestry Research Institute of Ghana, described that some of the most challenging things to do during the fieldwork were waking up daily at 3am in order to get to the field around 4am for predawn water potential measurements, as well as climbing of the trees at this hour of the day. They say: ‘The dry season CO2 exchange measurement was difficult and frustrating. One can spend over an hour or even a day on a single leaf, and the measurements are to be carried on three leaves per branch, as the protocol demands.’

Dr Imma Oliveras, senior study author and Deputy Programme Leader on Ecosystems at the Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, reflects on the field campaign: ‘To me this field campaign was an incredible enriching experience. These were busy days of knowledge exchange. I would be training local students on scientific methodologies, and they were teaching me about the local flora as well as about the local forests and of the Ghanaian culture and traditions.

‘Some forests had taboo days in which we were not allowed to go to the forest and we would use for catching up on lab work. We would also exchange knowledge in other aspects, such as cuisine. I learned to make fufu and I taught them to cook Spanish omelets. Scientifically, I enjoyed training the research assistants in both data collection, data curing and data analyses, and most participants are now co-authors of other related research.’

Image: Part of the team at base camp. © Yadvinder Malhi.

Image: Part of the team at base camp. © Yadvinder Malhi.

In our study we did not assess on how diversity changes affect ecosystem functioning. However, there is ample evidence showing that decreases in functional, taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity could cause loss of forest functions, such as resources uptake, cycling and biomass production and resilience to a changing climate. Therefore, the ecosystem functions of communities that show decreases across all three facets of diversity could be especially vulnerable under a drying climate.

Overall, our study found that drier forest communities have undergone biodiversity homogenisation due to a warming and drying climate, which could ultimately have negative impacts not only on the functioning of ecosystems but also on their contribution to people’s wellbeing and livelihoods.

Image: Heading into the field. © Yadvinder Malhi.

Image: Heading into the field. © Yadvinder Malhi.

The work was funded through a European Research Council Advanced Investigator Grant to Prof Yadvinder Malhi, coupled with a Royal Society Africa Capacity Building Award. The transects of field sites where this work was conducted were established with the support of a NERC Standard Grant.

Citation: Aguirre-Gutiérrez, J., Malhi, Y., Lewis, S.L. et al. Long-term droughts may drive drier tropical forests towards increased functional, taxonomic and phylogenetic homogeneity. Nat Commun 11, 3346 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16973-4

- ‹ previous

- 40 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?