Features

Female red junglefowl, the wild ancestor of the domestic chicken, may be able to optimise the immunity of their offspring by selecting sperm after mating with different males.

That's the conclusion from a study led by Oxford University researchers published in this week's PNAS.

'In natural populations, males can coerce females and selecting sperm after mating with multiple males is a safer way to control offspring paternity for a hen,' explains Dr Tom Pizzari of Oxford University’s Department of Zoology, one of the research team.

Whilst previous work has demonstrated that hens are able to select against the sperm of related males after mating, quite what triggers this response is a mystery.

The team focused their efforts on the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC), a gene complex that plays a key role in immune responses. 'Similarity at the MHC between two individuals is often a good proxy for their overall relatedness,' Tom tells me.

In the study the team looked for evidence of sperm selection after both natural matings and artificial insemination. Whilst there was strong evidence for sperm selection in the natural matings, evidence of this occurring with artificial insemination was much weaker.

'During natural mating hens appear to be able to assess their relatedness and genetic similarity with prospective partners,' comments Tom. 'One possibility is that the genetic profile of an individual at the MHC may be associated with olfactory cues, but the extent to which olfactory cues mediate kin recognition in birds remains unclear.'

The team's results suggest that hens may preferentially retain the sperm of males with a MHC different from their own. This could mean that rather than selecting sperm merely to avoid the risk of inbreeding, hens may select sperm in order to optimise the MHC diversity of their offspring, which translates into better immunity against a wider range of pathogens.

The findings are not just relevant to junglefowl or chickens:

'Mechanisms of female sperm selection are widespread, yet their functional significance has remained elusive,' Tom tells me. 'The results of our study suggest that some of these mechanisms may have evolved to allow females to optimise the genetic diversity of their offspring after mating with multiple males. These results may therefore have relevance for breeding programmes in animal productions and conservation biology.'

Scientists as eminent as Stephen Hawking and Carl Sagan have long believed that humans will one day colonise the universe. But how easy would it be, why would we want to, and why haven't we seen any evidence of other life forms making their own bids for universal domination?

A new paper by Dr Stuart Armstrong and Dr Anders Sandberg from Oxford University's Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) attempts to answer these questions. To be published in the August/September edition of the journal Acta Astronautica, the paper takes as its starting point the Fermi paradox – the discrepancy between the likelihood of intelligent alien life existing and the absence of observational evidence for such an existence.

Dr Armstrong says: 'There are two ways of looking at our paper. The first is as a study of our future – humanity could at some point colonise the universe. The second relates to potential alien species – by showing the relative ease of crossing between galaxies, it makes the lack of evidence for other intelligent life even more puzzling. This worsens the Fermi paradox.'

The paradox, named after the physicist Enrico Fermi, is something of particular interest to the academics at the FHI – a multidisciplinary research unit that enables leading intellects to bring the tools of mathematics, philosophy and science to bear on big-picture questions about humanity and its prospects.

Dr Sandberg explains: 'Why would the FHI care about the Fermi paradox? Well, the silence in the sky is telling us something about the kind of intelligence in the universe. Space isn't full of little green men, and that could tell us a number of things about other intelligent life – it could be very rare, it could be hiding, or it could die out relatively easily. Of course it could also mean it doesn't exist. If humanity is alone in the universe then we have an enormous moral responsibility. As the only intelligence, or perhaps the only conscious minds, we could decide the fate of the entire universe.'

According to Dr Armstrong, one possible explanation for the Fermi paradox is that life destroys itself before it can spread. 'That would mean we are at a higher risk than we might have thought,' he says. 'That's a concern for the future of humanity.'

Dr Sandberg adds: 'Almost any answer to the Fermi paradox gives rise to something uncomfortable. There is also the theory that a lot of planets are at roughly at the same stage – what we call synchronised – in terms of their ability to explore the universe, but personally I don’t think that’s likely.'

As Dr Armstrong points out, there are Earth-like planets much older than the Earth – in fact most of them are, in many cases by billions of years.

Dr Sandberg says: 'In the early 1990s we thought that perhaps there weren’t many planets out there, but now we know that the universe is teeming with planets. We have more planets than we would ever have expected.'

A lack of planets where life could evolve is, therefore, unlikely to be a factor in preventing alien civilisations. Similarly, recent research has shown that life may be hardier than previously thought, weakening further the idea that the emergence of life or intelligence is the limiting factor. But at the same time – and worryingly for those studying the future of humanity – this increases the probability that intelligent life doesn't last long.

The Acta Astronautica paper looks at just how far and wide a civilisation like humanity could theoretically spread across the universe. Past studies of the Fermi paradox have mainly looked at spreading inside the Milky Way. However, this paper looks at more ambitious expansion.

Dr Sandberg says: 'If we wanted to go to a really remote galaxy to colonise one of these planets, under normal circumstances we would have to send rockets able to decelerate on arrival. But with the universe constantly expanding, the galaxies are moving further and further away, which makes the calculations rather tricky. What we did in the paper was combine a number of mathematical and physical tools to address this issue.'

Dr Armstrong and Dr Sandberg show in the paper that, given certain technological assumptions (such as advanced automation or basic artificial intelligence, capable of self-replication), it would be feasible to construct a Dyson sphere, which would capture the energy of the sun and power a wave of intergalactic colonisation. The process could be initiated on a surprisingly short timescale.

But why would a civilisation want to expand its horizons to other galaxies? Dr Armstrong says: 'One reason for expansion could be that a sub-group wants to do it because it is being oppressed or it is ideologically committed to expansion. In that case you have the problem of the central civilisation, which may want to prevent this type of expansion. The best way of doing that get there first. Pre-emption is perhaps the best reason for expansion.'

Dr Sandberg adds: 'Say a race of slimy space aliens wants to turn the universe into parking lots or advertising space – other species might want to stop that. There could be lots of good reasons for any species to want to expand, even if they don't actually care about colonising or owning the universe.'

He concludes: 'Our key point is that if any civilisation anywhere in the past had wanted to expand, they would have been able to reach an enormous portion of the universe. That makes the Fermi question tougher – by a factor of billions. If intelligent life is rare, it needs to be much rarer than just one civilisation per galaxy. If advanced civilisations all refrain from colonising, this trend must be so strong that not a single one across billions of galaxies and billions of years chose to do it. And so on.

'We still don't know what the answer is, but we know it's more radical than previously expected.'

Meeting Alison Woollard over a coffee is a delight. It's clear she is a story teller. She is engaging, enthusiastic, chatty, fun, easy to relate to, has lovely turns of phrase and illustrates everything with great tales and examples. I thoroughly enjoy the conversation and my time with her.

But those are all incidental skills of a presenter. She also has a great story to tell: Where we all come from.

And that's surely why she's been chosen as this year's Royal Institution Christmas lecturer.

The Christmas Lectures are an institution in themselves. Broadcast annually since 1966 from the Royal Institution's tight, high-sided lecture theatre, they are a fixture in the TV schedule as soon as the turkey and present opening have finished and a cornerstone of science education and outreach in this country.

Started by Michael Faraday in the first part of the 19th century, the lectures have always been loaded with showpiece demo after demo to illuminate the latest in scientific understanding in an accessible way for children (and their parents).

Dr Alison Woollard is Dean, Fellow and Tutor in Biochemistry at Hertford College, and a University Lecturer in the Department of Biochemistry, where her research looks at the nematode worm as a model system for understanding embryonic growth and development.

Her Christmas lectures on Life Fantastic will uncover the transformation through which a single cell becomes a complex organism. She will look at where we come from, what makes us, how we grow and how we age, but also how we might want to harness this knowledge and the questions it raises.

The lectures will bring in all sorts of subjects: covering some of the working of cells, developmental biology, how morphology changes over time, and evolution and the role of chance in shaping us as organisms.

So at Christmas time, when many people around the world will be celebrating a miracle birth, Alison will be explaining the amazing process by which a newly fertilised egg cell divides and grows. Or as she says: 'How cells in the growing embryo know what to do in the right place at the right time. How cells, all with the same DNA instructions, know to become liver cells, eye cells or toenail cells.

'It's all about interpreting those instructions,' she explains.

While it quickly becomes clear to me that she will make a tremendous presenter, when Alison first received an email inviting her to put herself forward for the Christmas lectures, her first reaction was to delete the email.

A few days later, she tells me, she retrieved the email from trash so she could at least leave it sitting there in her inbox. She then did nothing for a week. After a subsequent email chasing her, she did then draft a short proposal for the lectures and sent it off. She was surprised to get an audition. 'I'm still a novice,' she protests, though she admits that won't be the case come the New Year.

The Christmas lectures can draw anywhere between 1 and 4 million viewers, and is likely to be BBC Four's biggest show over the Christmas period.

'It's an enormous privilege,' says Alison. 'Other lecturers have had letters years later from scientists who say they were initially inspired by watching them.

'If my lectures are able to inspire any of the children in the lecture theatre or those at home, then job done!'

She suspects that the TV audience has a range of ages and interests, but doesn't believe that is a problem. 'The lectures need to be accessible to children and adults alike, and I don't see much difference. I think you can begin with basic ideas and go right up to the cutting edge, guiding people through and taking them with you.

'In my case, I have my 10 year old daughter at home to try stuff out on, and my mum at the other end of the spectrum.'

She is keen to use her set of lectures to go beyond explaining the pure science, and also explore some of the issues and ethical dilemmas it can raise.

'Part of my area of science includes new cell-based medicine and genome sequencing,' Alison says. 'These technical advances are important and raise some issues. There is a tremendous opportunity to improve human health, and a consensus will need to be reached on the issues.

'For example, where do we draw the line on screening for genetic abnormalities in embryos? If when born, we are presented with the complete sequence of our genome, we will need to understand risk to interpret information on what our genes may say about our future health.

'These need to be discussed, not just by scientists but by the public more widely. There is an absolute responsibility for scientists to take their science into society.'

Alison is also very clear on the importance of 'science where we don't know where it is going to lead; science that is blue skies, curiosity-driven, non-impact led'. She adds: 'Many medical advances have been purely serendipitous, arising unexpectedly from studying a biological problem.'

She points to the example of the important biological process known as 'apoptosis', or 'programmed cell death'. This is a normally well controlled and regulated process that is important in the development of an embryo, and is also a way in which cells in tissues that are stressed or damaged are shut down and broken apart.

Alison explains: 'The process was first identified in the nematode worm. The process's importance became clear when mutants lacking an active cell death pathway didn't develop properly and the embryos would die.

'Apoptosis is also important in cancer formation in humans. The inability of cells to die when they should, coupled with the uncontrolled proliferation of cells can drive the growth of a tumour.

'The molecules involved in apoptosis are very highly conserved. Those in the worm are similar to those in a human tumour. Studying simple, model organisms such as the worm can have an enormous impact on cancer medicine and biomedicine in general.'

Alison notes that she is only the fifth woman to do the Christmas lectures since they began in 1825. 'Which is kind of shocking,' she says.

She believes that there is much still to be done to solve the poor representation of women in many areas of science. It's not that male scientists are necessarily discriminatory or sexist, she says, the biggest problem is the career path. The need to keep producing results and journal papers, to work all hours in the lab, to keep going to conferences, all the things you need to run a successful research group – it is hard to marry that with having a family.

Alison took six months' maternity leave for each of her children, but much of that time she was still running her lab. 'Who else would know my research to direct it?'

She adds: 'Looking back, it was detrimental to my own experience to try and do all these things at the same time.'

Wanting a sneak preview of the lectures, I ask about the demos the Christmas lectures are known for.

'The demos are not worked up yet,' Alison says, to my disappointment. 'Unlike chemistry, where you can put two chemicals together and get a big explosion but there is perhaps more difficulty building a narrative, biology has extraordinarily profound ideas but you need to find the bangs.

'A lot of biological material needs microscopy to see what's going on,' Alison points out. 'We'll need good microscopy and good projection to grab the attention. We're thinking about great, high tech ways of doing this,' she reveals. 'One thing I can promise - we'll see life unfurl before our very eyes.

'We can also balance this with audience participation. Biology lends itself quite well to games, and we're thinking about that too,' she says.

As we continue to enjoy the summer, there are some things about Christmas I can't think about yet: Christmas shopping, the heavy eating and drinking. But watching Alison's Christmas lectures is one thing I'm already looking forward to.

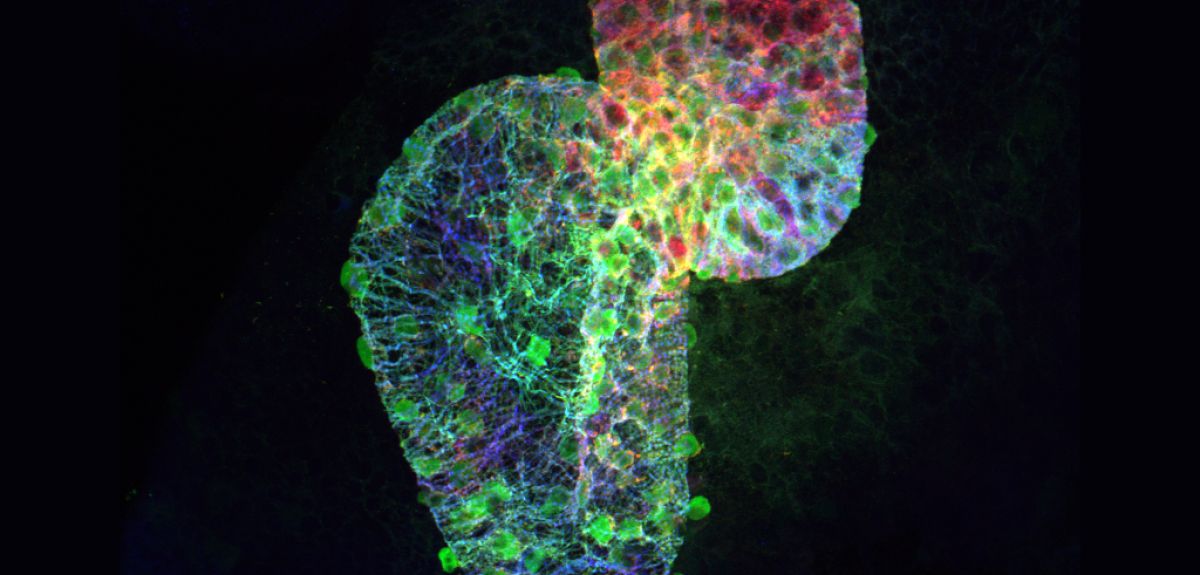

This picture shows the heart of a two-day-old zebrafish.

Its striking beauty has seen it win the Mending Broken Hearts prize in the British Heart Foundation's competition for outstanding images and videos from the research it funds.

The image was produced by Dr Jana Koth as part of her research at the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine at Oxford University.

Under the microscope, it is possible to see individual cells and the internal organization of the early heart as it grows and develops. The green cells are heart muscle cells, and the red and blue staining shows components that make up the muscle. The heart consists of two sections – the large, thin atrium (where blood flows in) and the smaller, thicker ventricle (where blood leaves the heart).

Remarkably, the hearts of zebrafish can repair themselves after damage, something which human hearts cannot do. The hope is that understanding this ability might in the future allow ways of prompting heart repair in people who have had heart attacks and develop heart failure, an area of research known as 'regenerative medicine'.

On winning the prize, Jana said: 'I'm stunned and delighted to receive this year's Mending Broken Hearts award. In the course of our regenerative medicine research we produce images like this all the time. They help us to uncover the secrets of the zebrafish. It's great to be able to take a step back and admire the beauty, as well as the biology, of this natural wonder.'

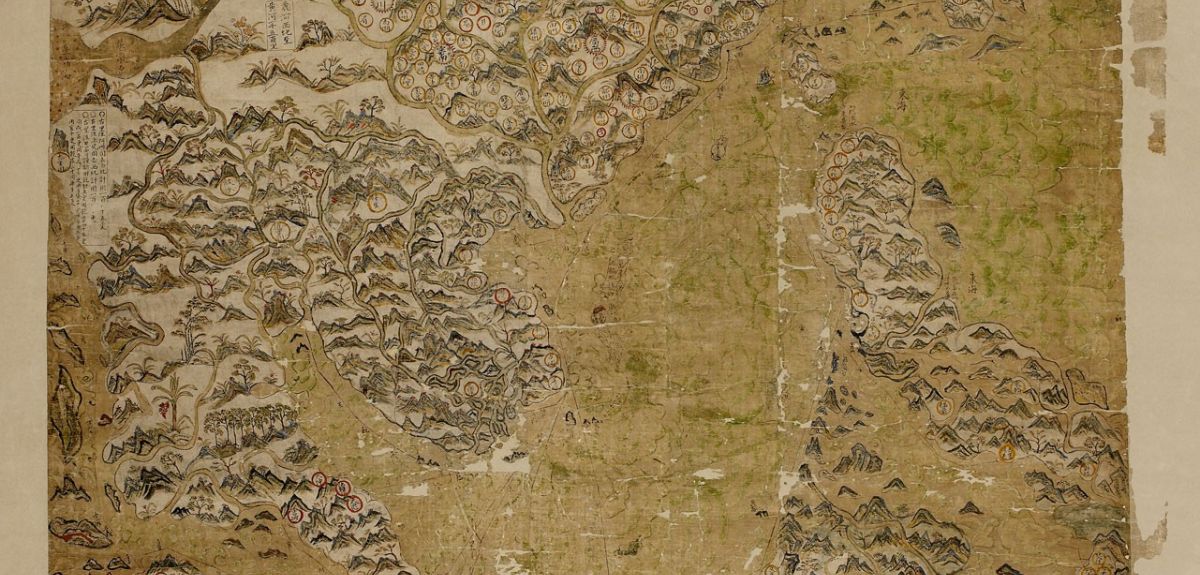

It was once described as 'a very odd map of China'. Today, the 17th-century Selden Map – which London lawyer John Selden bequeathed to Oxford in 1659 – is one of the treasures of the Bodleian Library.

David Helliwell, curator of Chinese collections at the Bodleian, explained: 'We don't know exactly when the map was made, nor do we know exactly where it was picked up in the Far East, but we imagine that it was probably made in 1620. It was acquired by a merchant of the East India Company and brought to London, where it passed into the hands of Selden. But we don't know exactly how, and we don't know exactly when.'

The newly-launched Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), which seeks to promote interdisciplinary collaboration, invited a number of scholars from different disciplines to cast their eye over the map. The resulting short film throws up a wide range of intriguing, interrelated perspectives.

Dr Kate Bennett, an English lecturer with a research interest in antiquarianism, was one of the academics invited to have their say. She said: 'What we can certainly say is that Selden knew a very interesting potential source of study and scholarship when he saw one. His works were things that he had collected to help his own scholarship, which was formidable.'

Rana Mitter, professor of the history and politics of modern China, hailed the value of the Selden Map in providing historical context for our understanding of the region today. He said: 'One of the things that has emerged from the research I have done is that things that we consider to be natural circumstances – the idea perhaps that China and Japan might be in conflict or hostile with each other – are actually often historically determined and often rather short-lasting. In other words, looking at the map gives you that longer-term view – a reminder that the kind of understanding we have of this immensely important region has to be informed by an understanding that trade routes, relationships, commerce and people engaging with each other has a long history. The map is a marvellous example of that.'

Ros Ballaster, professor of 18th-century studies, added: 'There was a lot of enthusiasm in the late 17th and early 18th centuries to find ancient cultures other than Greek and Roman classical culture, and that's a strong line in talking about China through the 17th and 18th centuries – as an alternative classical culture. I think that's what Selden is, in a way, trying to collect.'

As well as being an interesting object from a historical perspective, the Selden Map is also an important piece from an artistic point of view. Ros Holmes, a researcher in contemporary Chinese art, said: 'One of the most interesting things for me about the Selden Map is the sheer richness of the detailing itself. What first appears to be a 17th-century map about Chinese trade routes is actually a more complicated art historical object that attests to cross-cultural flows of knowledge and an exchange of ideas – not just about pictorial representation but about how China visualised itself in relation to the rest of the world.'

Mr Helliwell agreed about the visual impact of the map. 'It was probably a map that almost had a half aesthetic function and it was probably displayed in the house of a rich merchant,' he said. But for Mr Helliwell the most striking aspect of the map lies in its scope, and what it tells us about commerce in this period. The map extends to the whole of the Far East, with China only in the top half and the South China Sea at the centre. He said: 'This is a map drawn by ordinary people. It’s drawn by tradesmen – tradesmen who simply wanted to illustrate the routes on which they plied their trade.'

Image of the Selden Map courtesy of the Bodleian Library.

- ‹ previous

- 179 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?