Features

In the race to describe all of Earth's species before they go extinct it has been suggested that one species that is thriving is taxonomists.

Taxonomists are the people responsible for describing, identifying, and naming species – so far they have described around two million species. This could involve trekking into the jungle to discover new plants and animals but more often means poring over samples in existing collections and databases to unearth previously undescribed species.

'Taxonomic data, knowledge about species, underpins nearly every aspect of environmental biology including conservation, extinction, and the world's biodiversity hotspots,' explains Robert Scotland of Oxford University's Department of Plant Sciences.

If you want to describe all Earth's species before they vanish then the question of the taxonomy community's capacity, and the speed with which they can discover new species, becomes very important.

Some recent studies looking at trends in extinction counted the number of authors on each taxonomic paper and concluded that there was an expanding workforce of taxonomists chasing an ever diminishing pool of undescribed species. 'These findings contradict the prevailing view that there are six million species on Earth remaining to be discovered by an ever diminishing number of taxonomists, the so called 'taxonomic impediment',' Robert comments.

To test whether taxonomists were really a booming or endangered species, and what this might mean for species discovery, Robert and colleagues from Exeter University and Kew Gardens analysed data on the discovery of new plant species. A report of the research is published in the journal New Phytologist.

'What we found was that from 1970 to 2011 taxonomic botanists described on average 1850 new flowering plants each year, identifying a total of 78,000 new species,' Robert tells me. 'But while this period saw the number of authors describing new species increased threefold, there was no evidence for an increase in the rate of discovery.

'One recent idea is that species are becoming more difficult to discover and more authors are subsequently required to put in more effort to describe the same number of new species. We found no evidence for this as the lag period between a specimen being collected and subsequently described as a new species has increased.'

The team's study showed that, far from running out of new species, there are still around 70,000 new species of flowering plant waiting to be discovered. So why are taxonomy authors multiplying?

To get some context the researchers analysed the number of authors on papers in other subjects including botany, geology and astronomy over a similar period, 1970-2013, and then compared them to the data on taxonomy authors.

'We found that the increase in authors on taxonomy papers was in fact fairly modest compared to the 'author inflation' in other subjects including botany,' Robert explains. 'Our data show for geology that there were 1.8 authors per paper in 1975 but this has risen to 4.8 in 2013, and for astronomy, 1.6 authors per paper in 1970, 8.4 in 2013, so a fivefold increase.'

There could be many different reasons for author inflation; more interdisciplinary research, technological advances, the closer monitoring of performance indicators in scientific institutions that has led to the inclusion of students, lab assistants, junior staff and technical staff as authors on papers.

Robert comments: 'Using crude measures of author numbers to measure taxonomic capacity at a time of author inflation across all of science has the potential to be highly misleading for future planners and policy makers in this area of science.

'Our study found that in fact a very large number of new species are discovered and described by a very small number of prolific botanists, and more than 50% of all authors are only ever associated with naming a single species.

'It shows that there remain huge uncertainties surrounding our capacity to describe the world’s species before they go extinct.'

The clocks will be turned back 430 years at Christ Church on Saturday.

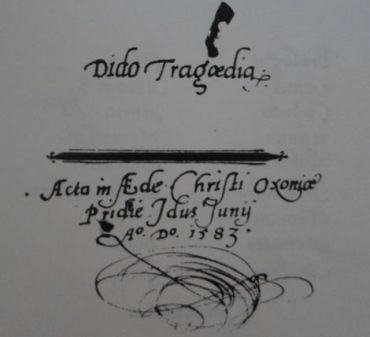

A little-known but fascinating Elizabethan play, rustled up to entertain the Polish ambassador Albert Łaski on his visit to Oxford in 1583, was the inspiration for this weekend's special event.

The evening of drama, served up alongside a banquet in Christ Church hall, is being organised by the University's Early Drama at Oxford (EDOX) project, run by a team of scholars and specialist film-makers.

Central to the sold-out event will be the performance of William Gager's Dido, translated from its original Latin by classicist and English scholar Elizabeth Sandis. The play will be staged in its original venue – once again in front of a representative of the Polish embassy, the Deputy Head of Mission, Dariusz Łaska.

Gager, who was a law student at Christ Church at the time, will be competing for top billing with Christopher Marlowe, whose Dido, Queen of Carthage will also be staged on the night.

Elizabeth Sandis: "We're trying to give people a chance to get to know dramatic material, some of it in Latin, that they may be unfamiliar with or find intimidating"

Elizabeth Sandis: "We're trying to give people a chance to get to know dramatic material, some of it in Latin, that they may be unfamiliar with or find intimidating"And the 16th-century feel will be completed by an authentic Elizabethan banquet, featuring such contemporary delicacies as vegetable and herb soup, roast pork belly with cinnamon gravy, spiced orange and wine jelly, and frumenty, a wheat-based 'porridge' traditionally served with venison or porpoise.

Elizabeth Sandis (pictured above), a DPhil candidate at Merton College specialising in the academic drama of Christ Church and St John’s College in 17th-century Oxford, said: 'We're trying to give people a chance to get to know dramatic material, some of it in Latin, that they may be unfamiliar with or find intimidating. The Christ Church event is the second in our series, after Magdalen last year, and next year we are thinking about a similar event at Merton.

'William Gager got really involved in the drama scene at Christ Church in the 1580s, so when the Polish ambassador was visiting at short notice and they needed to entertain and impress him, Gager was the person they turned to.'

The result was Dido, an adaptation of Virgil's epic Aeneid in the original Latin.

Elizabeth said: 'I've injected a few of the Latin verses back into my translation to give people the chance to hear how it would have sounded in 1583 – iambic senarii and lyric metres, and the Virgilian vocabulary.

'Gager was able to take entire sections of Virgil and incorporate them into his work. It was Elizabethan-style plagiarism but of a wholly acceptable kind because he was able to show off his skills as a Latinist and transpose Virgil's canonical lexicon into something new.

'At the time, everyone would have been familiar with the story of Dido and the fall of Troy, so it was a challenge for the playwright to dramatise that and do something clever with it.'

One example of Gager's playfulness involves a scene in which Aeneas's son, Ascanius, is brooding on the collapse of his home at Troy, having heard his father’s tale of the city’s fall the previous evening at dinner.

Elizabeth said: 'Dido asks him what the matter is, and he replies that he is thinking about his father's story from the night before and is beginning to imagine Troy in the features of a giant pudding on the banquet table – for example, the river Simoeis and the place where the wooden horse was brought in.

'It would have been a large marzipan dessert, and we’ll be recreating it on the night.'

The authentic Elizabethan menu to be enjoyed by the 240 guests was created by Christ Church head chef Chris Simms.

Gager's Dido will form part of a double bill on Saturday, sharing the stage with Marlowe’s Dido, Queen of Carthage. Both will be performed by all-male casts, just as they would have been in the late 16th century. Attendees will be able to compare and contrast the two adaptations ahead of a conference, titled 'Performing Dido', to be held by EDOX the following day.

EDOX was formed around 18 months ago by Elizabeth Sandis, Dr James McBain and Professor Elisabeth Dutton, who is directing Dido. The project, partly funded by the British Academy, is undertaking a systematic study of plays written and/or performed in the Oxford colleges between 1480 and 1650.

A highly effective new treatment for multiple sclerosis was approved yesterday by the European Medicines Agency, the regulator for drugs in Europe.

The drug can offer people with early multiple sclerosis many more years free from worsening disability, and Oxford played an important role in the drug's development.

Professor Herman Waldmann was involved in the early discovery work with the antibody drug at Cambridge University and brought a significant proportion of the research to Oxford when he moved here in 1994.

Once in Oxford, his team worked on the manufacture of the drug, contributed important new understanding of how the drug worked, and investigated the drug's application in a number of disease areas.

Cambridge continued to lead the clinical trials of the new drug in multiple sclerosis, and it is these which have now seen the drug approved by the European regulator.

The newly approved drug is called alemtuzumab and is made by the drug firm Genzyme, which will market the drug under the brand name Lemtrada.

'We are very pleased and proud of this outcome,' said Professor Waldmann. 'In particular, we have great admiration for the neurology team in Cambridge, with whom we have worked on this project for so many years. Their commitment and focus has been exemplary, and this has been a good example of basic and clinical science collaboration at its best.'

Although now approved for use in the EU, it still remains to be determined whether this drug will become a common treatment option for NHS patients, as the drug has not yet been assessed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for multiple sclerosis.

Multiple sclerosis affects 2.5 million people worldwide and approximately 100,000 people between the ages of 20-40 years in the UK. The disease sees the patient's own immune system attack their nerve cells, resulting in symptoms including numbness, tingling, blindness and even paralysis. Although some recovery may occur, the majority of patients relapse and then see repeated relapsing and remitting stages. Current treatments require frequent administration and are only moderately effective, reducing the relapse rate by only approximately 30%.

Alemtuzumab has the potential to make a great difference to patients, in terms of a better quality of life and not having to take treatments continuously.

'It is the first drug for multiple sclerosis that only needs to be given for a short course to provide long-term benefit,' explained Professor Waldmann, though the drug does need to be given before the disease has progressed too much.

The drug offers people with multiple sclerosis an improvement in their ability to function in their daily lives, a significant slowdown of disease progression and fewer disease relapses, he says. 'It compares favourably in terms of efficacy to most of the current treatments.'

Alemtuzumab reboots the immune system by first depleting a key class of immune cells, called lymphocytes. The system then repopulates, leading to a modified immune response that no longer attacks myelin and nerves as foreign.

But in doing so, roughly one third of multiple sclerosis patients develop another autoimmune disease after alemtuzumab, mainly targeting the thyroid gland and more rarely other tissues especially blood platelets.

Dr Alasdair Coles of the University of Cambridge explains: 'Alemtuzumab offers people with early multiple sclerosis the likelihood of many years free from worsening disability, at the cost of infrequent treatment courses and regular monitoring for treatable side-effects.'

The Cambridge research team is currently investigating how to identify people who are susceptible to this side-effect and seeing whether this side-effect can be prevented.

It was soon after the Nobel laureates Cesar Milstein and George Kohler invented the technology for making large quantities of monoclonal antibodies at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology that Herman Waldmann and others in Cambridge produced the first monoclonal antibody for potential use as a medicine. This antibody, then called Campath-1H and now known as alemtuzumab, was subsequently licensed for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.

In the 1980s, the scientists also began to explore the drug's use in autoimmune diseases, which occur when the body's immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue.

'By applying the drug in leukaemia, vasculitis, bone marrow and organ transplantation, we learned lot about how to use it, and this was the background for the application in multiple sclerosis,' explained Professor Waldmann.

Through the 1990s, while Cambridge neurologists began to explore the use of alemtuzumab as a treatment for multiple sclerosis, the Therapeutic Antibody Centre at the University of Oxford led by Professor Waldmann – a unique facility at the time – permitted the development and manufacture of alemtuzumab for clinical trials.

And through this partnership between Oxford and Cambridge, it was determined how the drug worked and its advantages in multiple sclerosis became clear.

Professor Alastair Compston and Dr Coles of Cambridge University led the subsequent clinical research to develop alemtuzumab in partnership with Genzyme.

Professor Compston said: 'This announcement [by the European Medicines Agency] marks the culmination of more than 20 years' work, with many ups and downs in pursuing the idea that Campath-1H might help people with multiple sclerosis along the way. We have learned much about the disease and, through the courage of patients who agreed to participate in this research, now have a highly effective and durable treatment for people with active multiple sclerosis if treated early in the course.'

The science of how rubbing a balloon on a woolly jumper creates an electric charge may help to explain how volcanoes generate lightning.

Volcanic plumes play host to some of the most spectacular displays of lightning on the planet but, whilst there are many theories, the exact mechanisms behind these natural light shows, and why some volcanoes see more lightning than others, are a mystery.

In a recent study published in Physical Review Letters researchers from Oxford University, and the Universities of Bristol and Reading, investigated what role volcanic ash particles rubbing together might play in making lightning bolts.

I asked Karen Aplin of Oxford University's Department of Physics, a co-author of the study, about volcanic lightning and how it can give insights into volcanoes on Earth and even other planets…

OxSciBlog: What do we think causes lightning in volcanic plumes?

Karen Aplin: Lightning in volcanic plumes is not completely understood, but there are several ideas about how it might work. Lightning is a giant spark that fires when large quantities of electric charge build up. Thunderclouds are made of water, ice and hail, and the electrification arises from collisions between light particles (ice) moving upwards in the cloud, and heavier water drops falling.

One way lightning in volcanic plumes could be generated is from ash particles colliding with each other. This is similar to the electric charge that can be generated by rubbing a balloon on a jumper.

Another way lightning can occur in volcanic plumes is from some volcanoes, like Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland, that have glaciers on top of them. When the volcano erupts, the glacier melts, which both causes huge floods and makes a big cloud of ice and water that becomes mixed with the volcanic plume. This mixture of cloud and plume can generate volcanic lightning by ice, water, and ash collisions in what's called a 'dirty thunderstorm'.

OSB: How did you set out to study the role of ash particles?

KA: We were interested in measuring the electric charging from ash particles colliding with each other. To do this, we dropped small samples of ash through a tube and measured the electric charge on the ash when it lands on a detector at the bottom of the tube. As the ash falls it rubs against other ash particles, and transfers electric charge (like the jumper and the balloon).

This experiment, carried out under controlled conditions in the lab at Oxford Physics, is the closest we can get to copying how the ash behaves in a volcanic plume. We took special care to make sure unwanted effects, such as the ash rubbing against the sides of its holder, were as small as possible so that we only measured the electric charge generated from the ash rubbing against itself.

The ash samples we tested were from the Icelandic volcanoes Grímsvötn and Eyjafjallajökull, and were generously given to us by the Icelandic Met Office. With the help of our colleagues in Earth Sciences and Geography at Oxford we measured the sizes of the ash particles, and sieved the ash to separate out the particles of different sizes, so we could understand how the size of the ash affected the electric charge transferred.

OSB: What do your results reveal about how variation in ash particles affects lightning?

KA: We found that some ash particles became more electrically charged than others, and that the size of the ash particles was important. If the particles have a wide range of sizes, they charge better than particles that are all of similar size.

Particles with the biggest difference in size from the largest to the smallest charged best of all. This suggests that frictional charging from particles rubbing together will be quite efficient in the plume near the volcano, where lightning is observed.

We also found that ash from different volcanoes had different electrical properties. For example, the ash from Grímsvötn charged up much more easily than the ash from Eyjafjallajökull. This is particularly interesting, as the Grímsvötn eruption produced much more lightning than Eyjafjallajökull. We don’t yet know why this is, but our lab measurements may be a first step towards understanding what part the properties of the ash play in volcanic lightning.

OSB: How could these findings help in the remote sensing of volcanic activity?

KA: Firstly, motivated by the dramatic lightning from the Grímsvötn eruption, the Icelandic Met Office is experimenting with lightning detection to provide additional early warning of eruptions. A better understanding of how volcanic plumes become charged could reduce false detections of volcanic lightning, and perhaps provide more information on the progress of the eruption.

Secondly, our results explain our previous curious observations, obtained with weather balloons, of electric charge within plumes distant from the volcano. This charge was unexpected, since the electricity on the particles when they were near the volcano should decay away relatively quickly.

Our results show that when the ash particles of different sizes rub against each other anywhere in the plume, they become electrified. Knowing that all plumes are very likely to be charged, no matter how far away from the volcano, means that we can start to develop new techniques to distinguish between clouds and volcanic plumes, the separation of which is crucial in mitigating hazards to aircraft.

OSB: What can they tell us about volcanism on other planets?

KA: Our findings are not limited to just terrestrial volcanoes. They are another step towards confirming that volcanic lightning occurs in planetary atmospheres.

One reason why this is important is that chemicals generated by lightning have been linked to the origins of life, so any planet that might have lightning may yield fundamental answers to some of the biggest questions there are. Electromagnetic signals from lightning also look promising for detecting volcanic activity as space probes fly past.

Top image: Lightning bolts in a volcanic ash cloud, Eyjafjallajökull Glacier, Iceland, via Shutterstock. Middle image: ash particles from Icelandic volcanoes used in the study.

A report of the research, entitled 'Triboelectric Charging of Volcanic Ash from the 2011 Grímsvötn Eruption', is published in Physical Review Letters.

Bees and other pollinators aren't just pretty creatures, they work for us.

In 2009 it was estimated that services provided by pollinators are worth an annual £510m in crops to the UK. That's why declines in many insect pollinator populations are a worry for economists and politicians as much as ecologists.

Take the bumblebee: the number of species has declined across Europe in the last 60 years and in Britain at least two species are thought to have gone extinct. Many other specialist pollinators are threatened and no one knows what effect this will have on overall pollination services.

There have been many theories about what's causing the decline and how we might halt it: recently insecticides called neonicotinoids have been suggested as a prime suspect but parasitic mites (Varroa destructor) and fungal disease (Nosema ceranae) have also been in the frame, not to mention the widespread destruction of pollinator-friendly habitats, such as wildflower meadows.

At an event in the Houses of Parliament this afternoon, UK politicians can find out about the current evidence concerning pollinator decline and what might be done to stop it. The event and accompanying POSTnote are the work of Rory O'Connor, a DPhil student at Oxford University's Department of Zoology and the NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology.

'The idea of POSTnotes is that they are an unbiased source of the best information about a topic and explain the science in a clear and understandable way,' Rory tells me. 'This is challenging when it comes to pollinator decline as there are opposing views, with neonicotinoids being a particularly controversial issue. What I had to do was go back through all the scientific evidence, summarise it, and then present it in just four pages.'

One of the big problems is how much we still don't know about pollinator populations. 'How do you monitor insect pollinator populations effectively? Which pollinators provide pollination services to which crops or wildflowers? In a lot of cases we don't know,' Rory explains. 'There's already some ongoing research into this but it's still early days and it's a fast-changing area, but then this is part of what makes it exciting to investigate!'

Rory's usual area of study is butterflies, so branching out to research a wide range of pollinators was quite a departure. The opportunity to work in Westminster came when he was awarded a British Ecological Society Fellowship at POST.

The event and publication of the note marks the end of his Fellowship but Rory comments that he's learnt a lot from it: 'My writing has improved, as has my analytical thinking and ability to synthesise a lot of complicated information – all particularly useful skills to hone for when I'm writing up my thesis. The simple but important things, like my confidence in asking questions and talking to people about my work and ideas, have also improved. I've also learnt a lot about the tremendously important world of insect pollinators.'

So what have we learnt about how to save the bees?

As well as the need to improve our fundamental knowledge of the role of insect pollinators and monitoring populations, the evidence Rory has gathered suggests that conserving and creating pollinator-friendly habitats could be crucial in providing refuges for at-risk species to feed and nest.

One answer could be to build on and extend current initiatives such as the UK government's 12 Nature Improvement Areas, Wildlife Trust's Living Landscapes, and the B-Lines project in Yorkshire, where farmers create corridors linking pollinator habitats. England's 402,000 km of hedgerows could also be used to provide new habitats.

Let's hope that the Westminster hive-mind can find an answer to the question of how to protect such valuable and productive insect species.

- ‹ previous

- 178 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?