Features

With the Golden Globes handed out and the Oscars looming, much of the media's attention is focused on the top films of the past 12 months.

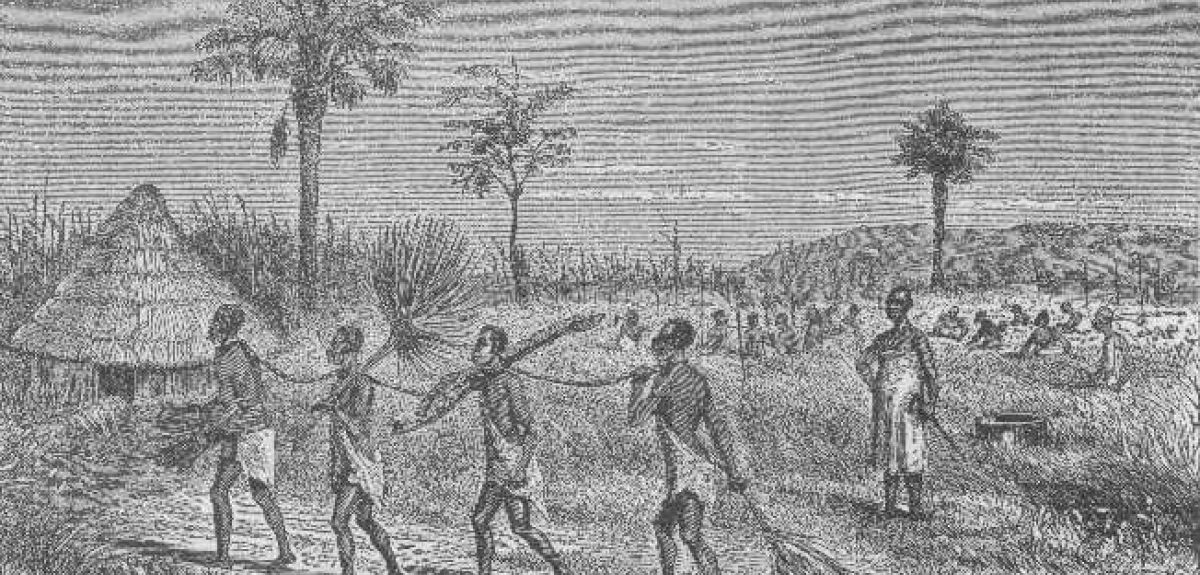

Chief among them is Steve McQueen's 12 Years a Slave, which has already scooped the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture amid a slew of other nominations and is the hot favourite to triumph at the Academy Awards in March.

The film, starring Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Fassbender, Lupita Nyong'o and Benedict Cumberbatch, is an adaptation of an 1853 memoir by Solomon Northup, a free-born African American from New York who was kidnapped by slave traders.

To coincide with the release of 12 Years a Slave, a BBC Culture Show special, presented by Mark Kermode, looked at the history and culture of slavery.

Oxford academic Jay Sexton, Deputy Director of the Rothermere American Institute (RAI), was one of the experts interviewed for the programme.

He said: 'To be a free black in the northern states would be much better than being a slave in the south, but there would be all sorts of limitations – both legal and political.'

Also interviewed was Richard Blackett of Vanderbilt University, Harmsworth Visiting Professor of American History at the RAI.

He said: 'Kidnapping was a major issue in mid 19th-century America. One can't quantify how many people were kidnapped, but a considerable number of free black people were kidnapped and sold into slavery.'

The programme can be viewed on BBC iPlayer here (link available until 12:04am, Saturday 1 February).

Leading figures from the arts, science and public policy came together in Oxford last night to discuss the value of the humanities in the 21st century.

Around 450 people packed into the University's Examination Schools to hear the views of, among others, Guardian chief arts writer Charlotte Higgins and Oxford mathematician Professor Marcus du Sautoy.

The event, which included a keynote speech from Dr Earl Lewis, President of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, kicked off the Humanities and the Public Good series, organised by The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

Among the audience given a warm welcome by the University's Vice-Chancellor, Professor Andrew Hamilton, were a number of school groups from across the UK.

Dr Lewis, in his speech titled 'In Everyone’s Interests: What it Means to Invest in the Humanities', said: 'Three quarters of a century ago, Virginia Woolf posed the question: if you had just three guineas to share, what would you support? In each age we face ostensibly insurmountable challenges that require choices to be made, resources to be allocated and areas to be ignored.

'The American Academy of Arts and Sciences argued in a recent report that we live in a world characterised by change, and therefore a world dependent on the humanities and social sciences.'

Dr Earl Lewis gave the keynote speech

Dr Earl Lewis gave the keynote speechHe added: 'We have to consider that the humanities continue to demonstrate the vibrant and dynamic tension between continuity and change. Longstanding disciplines such as literature, history and philosophy remain important to scholarship and discovery. And for nearly a quarter of a century we have also been embracing interdisciplinary scholarship.

'The humanities give us a fuller understanding of our world – past, present and future. The use of one's precious guineas in support of the humanities must start with a clear sense of its narrative, backed up by data. Investment then follows because the case for support is clear. That is why it is in everyone's interests to support the humanities and the public good – doing so advances our shared future.'

Responding to Dr Lewis's speech, Dame Hermione Lee, President of Wolfson College, Oxford, argued that those defending the humanities should not do so in an 'indignant, embattled or sentimental way'. She added: 'Why should we invest in the humanities? Because we're human.'

Charlotte Higgins, herself an Oxford classics graduate, called for the humanities not to be measured by the same criteria as the sciences, while Professor du Sautoy hailed the value of narrative, storytelling and collaboration in his own discipline.

Nick Hillman, Director of the Higher Education Policy Institute and a late addition to the panel, suggested that humanities scholars need to become better at engaging with policy makers, adding that the humanities have an unfortunate tendency to fight the previous battle rather than the current one.

And in an audience question and answer session chaired by Professor Shearer West, Head of the Humanities Division at Oxford, topics covered included why a sixth former should study a humanities subject at university; the value of longitudinal career studies into humanities graduates; the relationship between humanities study and employment prospects; and funding for the arts and humanities.

Information on the rest of the Humanities and the Public Good series can be found here.

Images: Stuart Bebb (stuartbebb.com)

Palaeobiologists at Oxford University have discovered a new fossil arthropod, christened Enalikter aphson, in 425-million-year-old rocks in Herefordshire. It belongs to an extinct group of marine-dwelling 'short-great-appendage' arthropods, Megacheira, defined by their claw-like front limbs.

Arthropods are a highly diverse family of invertebrates that include insects, arachnids and crustaceans, making up some 85 percent of all described animal species. The discovery and analysis of Enalikter aphson has given support to the notion that Megacheira came before the last common ancestor of all living arthropods in the tree of life. If correct, this would indicate that megacheirans were distant ancestors of all arthropods alive today.

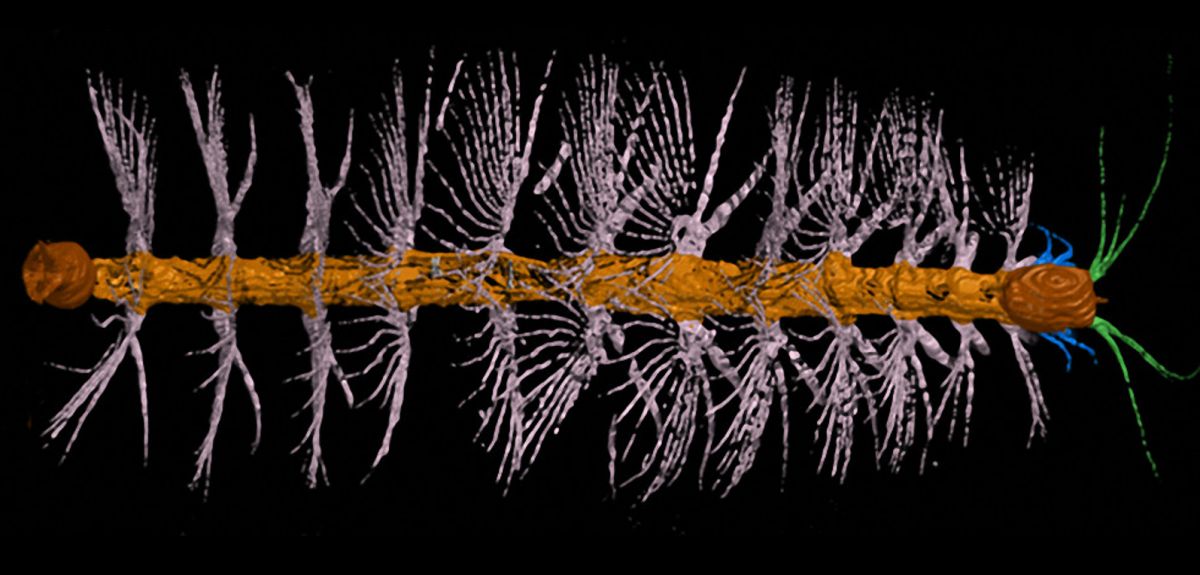

Enalikter was just 2.4 centimetres long with a rounded rectangular head, no eyes and a curved, whip-like feature protruding from in front of its mouth that may have been used in feeding – for example to capture smaller marine invertebrates.

At the rear end of its stick-like body there were two pincer-like projections that were attached to a primitive 'tail', and which may have been used for defence against predators. The extinct arthropod had no hard shell but is nevertheless remarkably well preserved in a hard nodule of minerals comprised mainly of calcite. Professor Derek Siveter, lead author of the study from the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and Department of Earth Sciences, said: 'Enalikter aphson had a soft and flexible body so it is incredible that it survived. The nodule acted like a womb and kept the creature free from decay and destruction, which would normally have happened very quickly. It meant it was able to survive all the earth movements and history that have happened since.'

The researchers were able to reconstruct the specimen in 3D thanks to its perfect preservation in the nodule. The nodule was investigated by optical tomography, a technique that can be used to create digital reconstructions of 3D objects using a series of finely-spaced images. To reconstruct Enalikter, the researchers imaged sequential surfaces of the fossil, spaced a mere 20 microns – thousandths of a millimetre – apart. These numerous images were then edited on a computer, in places pixel by pixel, to identify true biological structures from background 'noise'.

'In 3D it looks a bit like a tiny bottle brush, or even a Christmas tree. It is beautiful,' said Professor Siveter. 'It has provided us with exceptional data for the fossil record. Its soft body shell, or cuticle, is less than 10 microns thick. It was organic but has not decayed. That is amazing. Such exceptional preservation represents the jewel in the crown of palaeontology and provides so much more information than what does the typical shelly fossil record. It offers a rare window on the marine community back then.'

The newly-discovered animal, described in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, lived so long ago that the UK would have been south of the Equator near where the Caribbean islands are now.

'It would have lived on the seabed in water possibly up to about 100 or 200 metres deep, at a time known as the Silurian, when invertebrates were just beginning to move onto land,' said Professor Siveter. 'It would have been a very warm, subtropical environment.'

The Herefordshire site where the fossil was discovered has been a real treasure trove for Professor Siveter and colleagues for almost twenty years, providing valuable clues about what life on Earth was like in ancient times.

The BBC's new drama series The Musketeers – adapted from Alexandre Dumas' novel Les Trois Mousquetaires – made its debut on Sunday evening. Ahead of the screening, Dr Simon Kemp, Oxford University Fellow and Tutor in French, tackled the curious question of why the musketeers appear to have an aversion to muskets...

"So here it comes. Peter Capaldi – Malcolm Tucker as was, Doctor Who as shortly will be – is twirling his moustache as Cardinal Richelieu in trailers for the much-heralded BBC adaptation of Alexandre Dumas' Les Trois Mousquetaires (1844). It's always good to see British TV take on French literary classics. Let's hope The Musketeers has a little more in common with its source material than the BBC's other recent effort, The Paradise, for which I'd be surprised if the producers were able to put up the subtitle 'based on the novel by Émile Zola' without blushing.

"At any rate, the Dumas adaptation looks exciting, with plenty of cape-swishing, sword-fighting, smouldering looks and death-defying leaps. Plus one element that is markedly more prevalent than in the book itself: gunfire. One of the odder things about Dumas' novel for the modern reader is its singular lack of muskets.

"In the mid-1620s, when the story is set, the Mousquetaires are the household guard of the French king, Louis XIII, an elite force trained for the battlefield as well as for the protection of the monarch and his family in peacetime. They are named for their specialist training in the use of the musket (mousquet), an early firearm originally developed in Spain at the end of the previous century under the name moschetto or 'sparrow-hawk'. Muskets were long-barrelled guns, quite unlike the pistols shown in the trailer, and fired by a 'matchlock' mechanism of holding a match or burning cord to a small hole leading to the powder chamber. By the 1620s they were not quite as cumbersome as the Spanish originals, which needed to have their barrels supported on a forked stick, but they were still pretty unwieldy devices.

"There are lots of weapons in the opening chapters of Les Trois Mousquetaires, where D'Artagnan travels to the barracks and challenges almost everyone he meets along the way to a duel (including all three of the musketeers). Lots of sword-fighting, but no muskets in sight. One of the musketeers has nicknamed his manservant mousequeton, or 'little musket', and that is as near as we get to a gun until page 429 of the Folio edition, when an actual mousqueton makes its first appearance. A mousqueton is not quite a musket, though, and in any case it's not one of the musketeers who is holding it.

"The siege of La Rochelle in the later part of the story seems a more propitious setting for firearms, and indeed, as soon as he arrives at the camp, D'Artagnan spies what appears to be a musket pointing at him from an ambush and flees, suffering only a hole to the hat. Examining the bullet-hole, he discovers 'la balle n'était pas une balle de mousquet, c'était une balle d'arquebuse' ('the bullet was not from a musket, it was an arquebuse bullet', arquebuse being an earlier type of firearm). We are now 586 pages into the story, and starting to wonder if Dumas is playing a game with us.

"The suspicion is heightened when the musketeers take a jaunt into no man's land for some secret scheming away from the camp: 'Il me semble que pour une pareille expedition, nous aurions dû au moins emporter nos mousquets,' frets Porthos on page 639 ('It seems to me that we ought to at least have taken our muskets along on an expedition like this'). 'Vous êtes un niais, ami Porthos; pourquoi nous charger d'un fardeau inutile?' scoffs Athos in return ('You're a fool, Porthos, my friend. Why would we weight ourselves down with useless burdens?').

"The key to the mystery of the missing muskets is in these lines. Their absence from the novel up to this point is simply for the historical reason that the heavy and dangerous weapons were appropriate for the battlefield, not for the duties and skirmishes of peace-time Paris. Even when his heroes are mobilized, Dumas remains reluctant to give his musketeers their muskets. Remember that, writing in the 1840s, Dumas is closer in time to us today than he is to the period he's writing about, and his gaze back to the 17th century is often more drawn to romance than historical accuracy (as the cheerfully pedantic footnotes in my edition point out on every other page).

"For Dumas, the charm of his chosen period lies in the skill and daring of the accomplished swordsman, and his breathless narrative can wring far more excitement from a well-matched duel of blades than it could from a military gun battle. Heroism in Dumas is to be found in noble combat, staring your opponent in the eye as you match his deadly blade with your own, not in the clumsy long-range slaughter of unknowns. Musketeers his heroes must be, in order that they might belong to the royal guard and thus play a role in the dark conspiracies hatched around the King, the Queen and her English lover by Cardinal Richelieu, the power behind the throne. But the muskets themselves are surplus to requirements.

"Dumas does relent a little on his musket-phobia by the end of the novel. On page 645, the musketless musketeers fire at their enemies using weapons grabbed from corpses. And finally, on page 705, when Richelieu catches the four friends conspiring on the beach, we are at last granted a glimpse of the soldiers' own guns: '[Athos] montra du doigt au cardinal les quatre mousquets en faisceau près du tambour sur lequel étaient les cartes et les dès' ('He pointed out to the cardinal the four muskets stacked next to the drum on which lay the cards and dice').

"As far as I can make out, this is the only point at which we see the musketeers with their muskets in the whole story, and it seems a fitting way to present them to the reader: lying idle while the musketeers are occupied with other, more important amusements."

This post originally appeared on the outreach blog of the French sub-faculty at Oxford University.

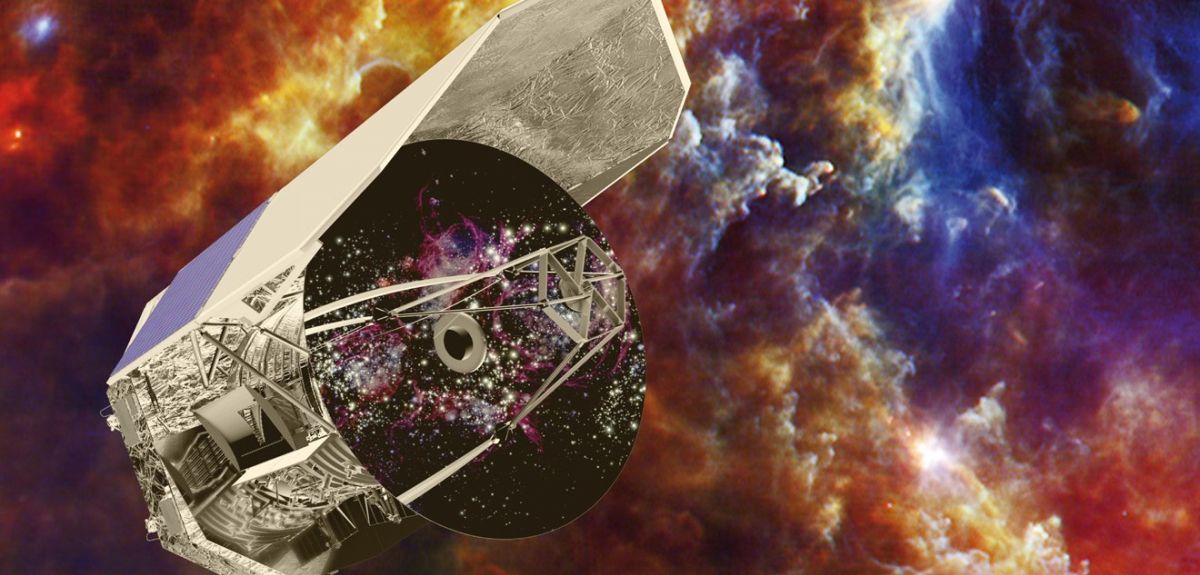

Luminous galaxies far brighter than our Sun constantly collide to create new stars, but Oxford University research has now shown that star formation across the Universe dropped dramatically in the last five billion years.

The research, co-led at Oxford by Dr Dimitra Rigopoulou and Dr Georgios Magdis from the Department of Physics, showed that the rate of star formation in the Universe is around 100 times lower than it was five billion years ago. They also showed that some luminous galaxies could create stars on their own without colliding into other galaxies.

The findings, published in the Astrophysical Journal, suggest that most of the stars in our universe were born in a 'baby boom' period five to ten billion years ago. The observations were made using the European Space Agency's Herschel Space Observatory.

I asked lead author Dr Rigopoulou to explain the research and what it tells us about the birth of stars.

OxSciBlog: What has changed in the last five billion years?

Dimitra Rigopoulou: There is clear evidence that the galactic-scale physical processes that initiate the formation of stars in the most luminous galaxies in the Universe have changed. Locally, luminous galaxies that produce a large volume of stars are almost always associated with galaxy interactions or merging. When galaxies collide, large amounts of gas are driven into small, compact regions in the galaxies causing stars to form. This process results in a highly efficient conversion of gaseous raw materials into stars. However, we found that many galaxies were able to form stars without colliding a few billion years ago.

OSB: Why is this important?

DR: We know that the majority of the stars in our Universe were born in massive, luminous galaxies. Our results change our understanding about how stars were formed in these systems. Consequently, our view about the way the majority of stars formed in our Universe must change.

OSB: Why is it surprising that non-colliding disk galaxies can create stars?

DR: Normal disk galaxies are unperturbed systems that undergo a slow and steady evolution. So, by discovering normal disks with very high star formation rates we have uncovered a fundamental change in the galactic-scale process of star formation in the most efficient star-forming galaxies of our Universe.

OSB: What results surprised you the most and why?

DR: Over the last decade there have been various lines of evidence suggesting that in the early Universe around ten billion years ago, luminous galaxies were quite different from what we observe in the present day.

To our surprise, we found that this change already occurred less than five billion years ago, suggesting that the changes were very rapid and did not happen over long timescales. We measured ionised carbon, which is produced when the gas in the galaxy cools down and collapses initiating the formation of stars. The ionised carbon levels from luminous galaxies five billion years ago were very similar to those from ten billion years ago but completely different to today's galaxies. Something important must have happened to change galaxies' behaviour to what we see today.

OSB: Do we know why galaxy behaviour is changing?

DR: We think there are two main factors responsible for the change in the behaviour of galaxies: one is the amount of gas that is available to them and the other is the gas 'metallicity', the proportion of matter made up of chemical elements other than hydrogen and helium . As galaxies get older, they use up their gas to make stars so they run out of the raw material needed to create more stars. The availability of large gas reservoirs means that some galaxies can make stars efficiently without the need of interactions to trigger the star forming activity, as happens in local galaxies. Metallicity, on the other hand, is very closely related to star formation so a change in the specific make up of the gas can have a huge impact on the way star formation proceeds and hence affect a galaxy’s behaviour.

While our results have highlighted these important changes in the way galaxies form their stars as they turn older we now have to follow these leads and firmly establish these points of change in the fascinating lives of these luminous infrared galaxies.

- ‹ previous

- 175 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?