Features

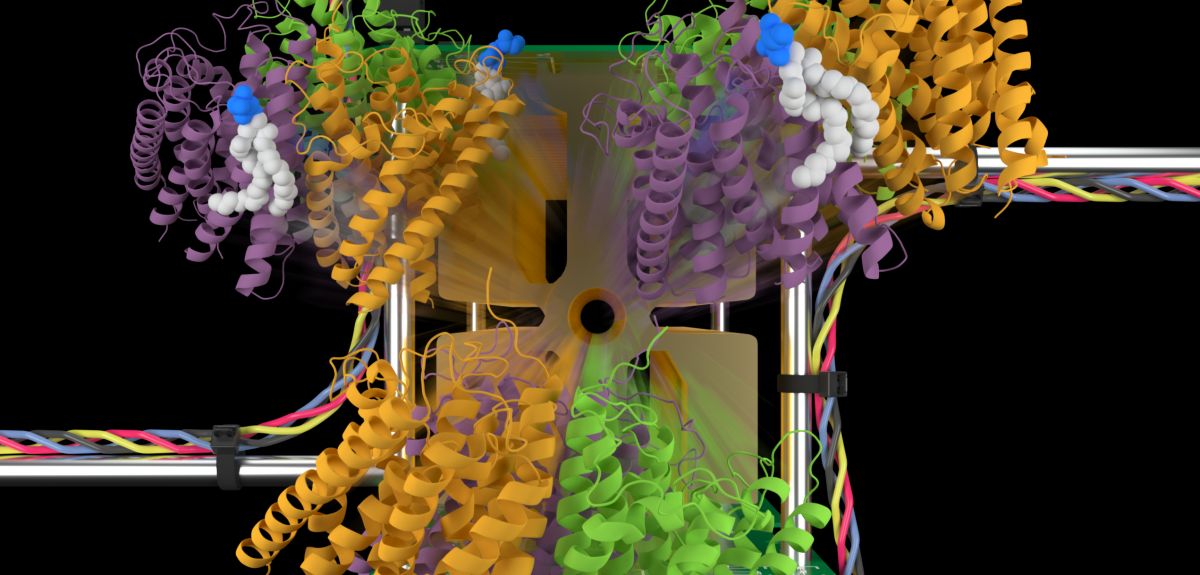

Protein machineries embedded in the membranes of our cells act as 'gatekeepers' controlling everything transported in and out of every cell in our bodies.

Because these machineries, called membrane embedded proteins, are vital to the way our bodies function they are the target of at least 40% of drugs. But one of the problems of targeting these proteins is that they are known to be influenced by lipids and current methods often struggle to distinguish between the effects of lipids and drugs.

Now Oxford University researchers report in Nature that they have found a way to assess what effect lipids have on proteins by measuring how lipids resist being 'unfolded'. By using a technique called ion mobility mass spectrometry, that propels proteins and their lipids into a vacuum, they discovered that by measuring resistance to unfolding they could rank these lipids based on their ability to stabilise membrane proteins.

'We could see lipids binding to membrane proteins but we couldn't work out how to rank their effects,' Carol Robinson of Oxford University's Department of Chemistry, who led the research, tells me. 'However, by measuring resistance to unfolding we were able to observe big differences between the lipids.

'We have found that they can change their overall stability - quite dramatically - and this can lead to structural changes and also has implications for the function of membrane proteins. They were much more intimately linked than we first thought - important for function and also for conformational change.'

She explains that the research was originally considered controversial since it was unclear how relevant measurements made using such techniques would be: 'We didn't know that the measurement of resistance to unfolding would correlate so well with function and stability. The unfolding is performed in the gas phase while function and stability take place in a biological membrane – it is surprising that there is such a good correlation.'

The new findings could have important implications in the search for new drugs:

'This approach is readily applied to drugs since the same methods of ranking lipids can be used to rank drug molecules,' Carol explains. 'We also think that we will learn a lot about the synergy between lipid and drug binding - something that is often very difficult to assess with current techniques.'

An Oxford University choir has been featured on Hong Kong television as part of its most recent tour.

The Oxford Gargoyles, a long-established jazz a cappella group, visited Hong Kong and Macau to perform at the first Meeting Minds: Oxford Asia Alumni Weekend, as well as the Cathay Pacific/HSBC Hong Kong Sevens rugby tournament and the Oxford University Society of Macau's fundraising concert in the historic Teatro Dom Pedro V.

The 14-strong choir's dazzling black-tie vocal jazz performances were a huge hit throughout the tour, as were the workshops it held at 10 local and international schools in the region. In total, the group put on more than 30 concerts at a wide range of venues, including Hong Kong City Hall, the Hong Kong Fringe Club, arts exhibitions, restaurants and shopping malls.

Media appearances included a performance at the Radio Television Hong Kong studio and a news item on the school workshops broadcast on TVB Pearl.

The Gargoyles have now returned to Oxford and are looking forward to performing at a host of college balls, garden parties and weddings this summer. Their end-of-term concert will be held at Magdalen College on Tuesday 10 June and will be raising money for the student-run mental health charity Student Minds. The choir will also be performing at the Edinburgh Fringe in August.

The Oxford Gargoyles would like to thank the Oxford University China Office, the Oxford University Society of Macau and the many Oxford alumni who supported the tour.

An Oxford researcher is among 10 scholars chosen as part of a scheme to find the academic broadcasters of the future.

Will Abberley

Will AbberleyWill Abberley has been named as a New Generation Thinker 2014 by BBC Radio 3 and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

The nationwide initiative, which receives hundreds of applications from early-career academics each year, seeks out the brightest minds with the potential to turn ground-breaking ideas into fascinating programmes.

The winners will spend a year working with BBC Radio 3 presenters and producers to develop their research into broadcasts. They will make their debut appearance on the arts and ideas programme Free Thinking on Tuesday 10 June and will also have the opportunity to develop their ideas for television.

Will, a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in English, was picked from a group of 60 finalists following a series of day-long workshops at the BBC's bases in Salford and London. He told Arts Blog about his excitement on hearing he had been chosen as a winner.

How does it feel to be named one of the BBC Radio 3/AHRC New Generation Thinkers for 2014?

Really exciting! I've always been interested in communicating research beyond the academy and this is a unique opportunity for doing that. As academics, I think it is important for us to be able to explain our work and why it matters to everybody, not just our colleagues. It's a very competitive process and the other applicants I saw were all great, so I have to say I'm pretty surprised to have been selected!

How would you sum up your research?

My current project explores the history of the concept of natural mimicry, and its impact on Victorian culture. Natural mimicry is basically when organisms pretend to be things they are not. For example, insects which are camouflaged by their resemblance to leaves, or butterflies which resemble the patterns and colours of other, inedible species in order to ward off predators. Naturalists like Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Walter Bates were the first to argue that deceptions like these evolved through natural selection; that nature was constantly producing tricks and imitations. This idea was disturbing for two reasons. First, it disturbed religious models of a world created by a moral, truth-loving God. Second, it complicated scientific observation and objectivity, since mimicry involved imagining the mental processes of different animals as they interpreted each other's appearances in the wild. The naturalists had to put themselves in the position of predators and prey and try to see the world through their animal point of view.

I come from a literary background, so I am focusing on how naturalists used certain forms and genres of writing to communicate the controversial idea of natural mimicry to public audiences. I want to argue that the scientific travel narrative was particularly useful for this end, as it enabled the naturalists to retell the stories of their dramatic encounters with mimicry and camouflage in wild environments across the world. My research also concerns how Victorian science and literature imagined the role of mimicry and deception in psychology and sociology. Were these phenomena primitive and bestial or did they hold the key to human evolution and even civilization?

What does being named a New Generation Thinker mean for your career?

Well, humanities scholars are always keen these days to demonstrate the 'impact' of their work, and I think this will be a pretty good way to do that! I am genuinely passionate about broadcasting – between degrees, I worked as a radio journalist – and I hope to combine that passion with my academic research interests in many ways. In the longer term, I would love to make a big series on TV or radio that would enthuse wider audiences about the fascinating intersections between literature and science.

A Europe-wide project which began at Oxford University has received the backing of Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Europeana 1914-1918 makes digital copies of material related to the First World War and makes them freely available online. It follows the model of Oxford University’s Great War Archive, which digitised more than 6,500 items contributed by the British public between March and June 2008.

Europeana 1914-1918 extended this project across Europe, and more than 90,000 items have now been added to the website. Oxford University is still involved in this wider project, helping to run family history roadshows across Europe to which members of the public bring memorabilia and stories of their family’s life during the Great War.

Speaking in her weekly video podcast, Ms Merkel said: 'I am happy that many people participate and that history also becomes more comprehensible … This is a great thing.' She added that such a project makes clear that it is 'better to negotiate 20 hours longer and talk, but never come back to such a situation in the middle of Europe'.

Dr Stuart Lee of Oxford University’s English Faculty and IT Services said: 'It is wonderful to see an Oxford-initiated project now being picked up and discussed by one of the main leaders of a European country. More so that this is in Germany where we are witnessing possibly the first engagement by the general public in Germany with the memory of the war.'

He added: 'The centenary of the First World War offers us an important opportunity to reflect on the war but also to challenge prejudices across Europe, and Oxford's Great War Archive project which led to the Europeana 1914-1918 initiative had this as one of its main aims by allowing the public to expose material they had held for nearly a century and explain its importance.'

The archive has already turned up some interesting discoveries, including two postcards written by Adolf Hitler in 1916 to his comrade Karl Lanzhammer.

Anyone who has items relating to the First World War is encouraged to add these to the website.

The Oxford undergraduate recently commemorated by the Football Association (FA) as 'England's first football captain' is among the new lives added in the latest update to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography today.

Cuthbert Ottaway (1850-1878) was in his final year studying classics at Brasenose College when he captained the England association football side against Scotland at Glasgow on 30 November 1872 in what sports historians regard as the first ever official international football fixture. The match ended in a 0-0 draw.

In the 150th anniversary year of the Football Association, in 2013, a restored memorial to Ottaway was unveiled in Paddington Old Cemetery, London, where he is buried. At the time, current England captain Steven Gerrard said: 'I never knew Cuthbert Ottaway's story before. He had the honour of being the first England captain and it is great that what he achieved is being recognised in this way.' Now, as the FIFA World Cup approaches, Ottaway has found a place in the Oxford DNB.

In his own lifetime, Ottaway was better known as a cricketer, batting alongside W G Grace for the 'Gentlemen of England'. He captained Oxford University Cricket Club to victory over Cambridge University at Lord’s in 1873.

In total, Ottaway represented Oxford at five sports against Cambridge: cricket, real tennis, rackets, athletics, and association football. He also captained the newly-founded Oxford University Association Football Club to victory in the FA Cup final in March 1874.

When Ottaway returned to Oxford in June 1874 to take his BA degree, there was a great ovation for him in the Sheldonian Theatre in recognition of his sporting achievements. The degree ceremony was held in the morning; that afternoon, Ottaway was back in London, where he scored a century at Lord’s for the Bar against the Army. His legal career was sadly cut short by his early death, aged only 27, in 1878.

Dr Mark Curthoys, an Oxford University historian who wrote the Oxford DNB entry for Ottaway, says: 'Ottaway was well known in his own lifetime as a sporting phenomenon, representing his university at five sports. He can now be viewed in the longer term as one of the first generation to organize and play association football on the national stage.'

The Oxford DNB is freely available through public libraries, and by remote access to public library members. It is the national record of men and women who have shaped British history and culture, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. It is overseen by academic editors at Oxford University, UK, and published by Oxford University Press.

- ‹ previous

- 169 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?