Features

Why are we entertained by evil? Who has the capacity to commit evil? These questions were considered by 90 delegates from around the world who met in Oxford today (Friday 27 June) for a conference exploring the concept of evil, and what role it plays in human experience.

The conference, entitled Evil: Interdisciplinary Explorations, was organised by Oxford University theologian Kate Kirkpatrick and linguist Marieke Mueller, with the support of The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), Wycliffe Hall, the Faculty of Theology and Religion, and the Oxford Centre for Christianity and Culture.

Discussions at the conference touched on evil in many forms: from fictional representations of devils, monsters and murderers, to institutional evil and the relationship between evil and technology.

Kate Kirkpatrick, of St Cross College and the Faculty of Theology and Religion, said: 'We've had a fantastic level of interest, including delegates from North America, Europe, and Australia, as well as around the UK. We're aiming to get people from different fields to talk to each other and share their ideas.

'It's a question of dispute whether it’s possible for anyone "not to have a bad bone in their body", or to be perfectly evil. Do we call individual actions evil, or do people have evil characters?

'If someone is pure evil, does that make them responsible for their actions, or do they not have a choice? If you put ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances they will sometimes do heinous things.'

Many speakers explored our cultural fascination with evil, from Shakespeare to serial killers. Professor Terry Eagleton of Lancaster University gave the closing lecture, on William Golding’s novel, Pincher Martin, which deals with a shipwrecked man’s struggle to survive and eventual descent into madness.

Horror films and contemporary television also came under scrutiny. 'It makes one wonder whether evil is a more interesting concept than good,' said Kirkpatrick.

The conference was held in the Andrew Wiles Building and Radcliffe Humanities Building, part of the University's Radcliffe Observatory Quarter.

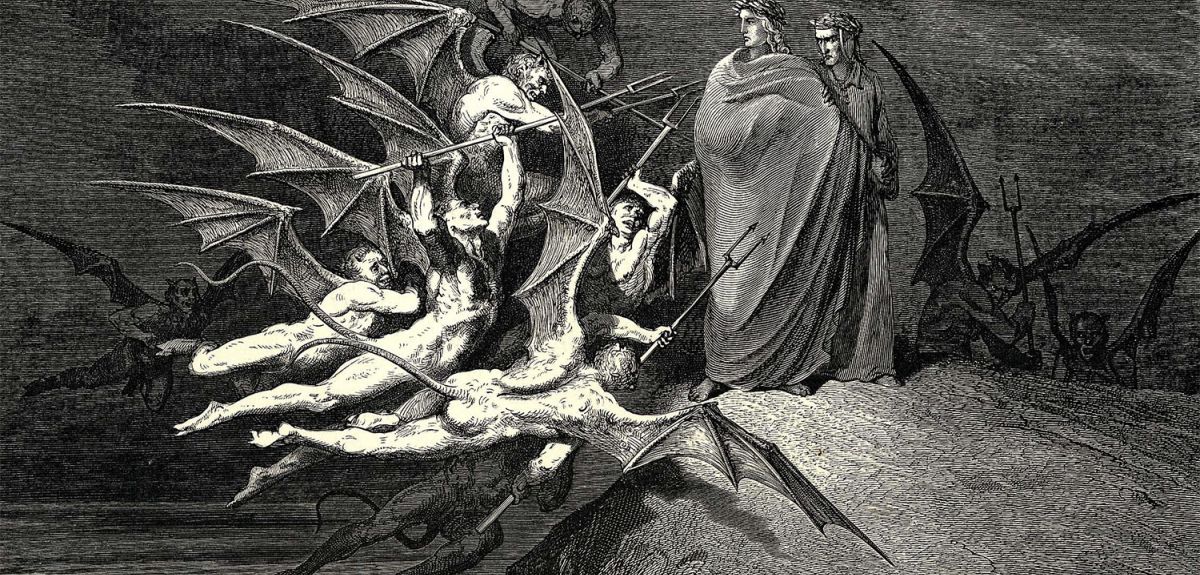

Image: A depiction of evil from Gustave Doré's illustrations to Dante's Inferno.

The weirdness of quantum theory has caused some physicists, including Einstein, to suggest that it doesn't give us a picture of the way the world is.

Viewed this way, quantum theory might just be a mathematical tool for making predictions about an object without describing what it's really like. If this was true, a single object could be described by more than one quantum state.

Now scientists at Oxford University and the University of Sydney have shown that the idea of objects with multiple quantum states may be an illusion that could vanish as experimental measurements become more precise. If they are correct it could help to chart the limitations of quantum information processing [QIP].

A report of the research is published this week in Physical Review Letters.

The team liken trying to understand the nature of objects from experimental observations of quantum states as a bit like trying to determine how a playing card was chosen from being dealt a single playing card.

'Imagine a deck of 52 playing cards is shuffled by a special shuffling robot,' explains Owen Maroney of Oxford University, an author of the study. 'The robot has two settings, with the first it deals you a red card drawn at random and with the second it deals you one of the four aces at random. You have to deduce what's really going on from just one card, but if you are dealt the ace of hearts then you can't distinguish if the robot was using setting one or two.'

This is because the cards dealt out by settings one and two overlap in the case of the ace of hearts. Two different quantum states can also show 'indistinguishability' – sometimes you just can't tell whether an object is in one quantum state or another. This led some physicists to suggest the same explanation.

'Rather like with the playing cards, when quantum states seem to overlap the problem could lie in the way that the state is prepared,' Owen tells me.

'What we have shown is that this puts a strong limitation on experiments performed on three different states, and we've found quantum states that exceed this limitation.'

This question of whether quantum states are grounded in reality or not is an important one for anyone trying to use the 'weirdness' of the quantum world to do advanced calculations or form the basis of a quantum computer.

'We're exploring the fundamental limits of what information can be squeezed out of quantum states from what we can detect,' Owen explains.

The team are currently working with three different labs on experiments to see whether the limitations they have scoped out can be tested.

'The best experimentalists are only just reaching the 99% accuracy in reading quantum states that we need to be able to test our ideas,' Owen says. 'We still don't know for sure what the real boundaries are between what classical and quantum computing can do, it may be that we are reducing quantum problems to classical ones. Our work isn’t just about the limitations; it could lead to new opportunities for quantum information processing.'

Forget Cannes, move over Sundance. The Radcliffe Humanities building will host a film festival on public health next week.

The Public Health Film Festival, which will take place on Friday 27, Saturday 28 and Sunday 29 June, has been organised by public health students and practitioners from Oxford.

Through the medium of film, the organisers aim to facilitate discussion and debate about the big public health issues of the day and provide a springboard for action to reduce poverty, improve social inclusion, and provide advocacy for marginalised communities.

The Oxford Centre for Research in the Humanities (TORCH) is hosting several screenings and sponsoring a prize, along with the Nuffield Department of Population Health. TORCH's director Dr Stephen Tuck says: 'We are delighted to support the Public Health Film Festival. It demonstrates how arts and sciences can work together for the public good, by using techniques of film and advocacy - which are more often associated with the arts - to support scientific, evidence-based cases for reform to public health policies.'

One of the films, Unborn, is shown below. Directed and produced by Dr Oliver Rivero, senior health economist at Oxford's National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, it shows a young woman who suffered a miscarriage dealing with feelings of sadness and self-blame when she sees a happy mother with her baby in a park.

Another film that will be shown, called 'Sea of change: Walking into trouble', has been used for advocacy for the partially sighted and blind at Number 10 Downing Street and the House of Lords.

Sarah Gayton, who made the film to support her campaign, says: 'I decided to use to film as I thought this way the people in charge of the safety of the public could see first-hand the negative impact this road system was having on the blind and partially sighted people of the UK.'

Dr Stella Botchway, a Public Health Speciality Registrar in Oxford University's Nuffield Department of Population Health and organiser of the Public Health Film Festival, says: 'Public health in the UK and around the world is the key issue of our time. Diet, social inequality, the global economy, the control of infectious diseases and climate change are just a few of the challenges facing public health experts.

'The Public Health Film Festival passionately believes that both film and public health have the ability to change people’s lives, which is why we have brought these two disciplines together in order to inform and inspire the public.'

A full schedule of events can be found on the Public Health Film Festival’s website. Screenings and talks will take place in Radcliffe Humanities on Woodstock Road and the Phoenix Picturehouse on Walton Street.

Artwork by final-year art students at Oxford University will go on show this weekend at the annual Ruskin Degree Show.

Taking place from 21–23 June at the Green Shed, Osney Mead, with a private view on 20 June, the public exhibition will feature a bold and diverse range of work in a variety of forms and on a number of themes.

The show, which will present the work of the 24 Ruskin School of Art students graduating this year, is always eagerly anticipated and generates lively debate among those who attend. Last year’s exhibition attracted more than 1,000 visitors from Oxford and further afield.

Jason Gaiger, Head of the Ruskin School of Art, said: 'The Ruskin Degree Show is one of the highlights of the year, attracting interest across the University and bringing a large number of visitors from beyond Oxford who want to experience at first hand cutting-edge contemporary art and to identify the next generation of leading artists.'

Melanie Gurney, one of the students organising and exhibiting at this year’s show, said: 'The quality of the artwork in this year's show is outstandingly high. The size of the Green Shed allowed many of us to be bold and ambitious. The Ruskin degree show 2014 will be bigger and better than ever before.'

Sponsors of this year’s event are HMG Law, Bonhams, and Joshua Horgan Print and Design.

Participants in last year's Degree Show have gone on to win awards for their art, including James Lomax, who secured a Sky Arts Scholarship, and Jack Stanton, who won the Saatchi/Channel 4 New Sensations Prize.

James said: 'Degree shows are a pivotal moment in an artist's career – they allow for both engagement in creative practice and curatorial exercise while preparing the artist for life past art school as they look to seek funding and venues from outside sources to allow them to showcase their work. My degree show gave me the necessary skills to build upon, and these skills have allowed me to successfully continue my career as an artist past art school.'

The Degree Show is open to the public and free to enter from Saturday 21 to Monday 23 June from 12pm-5pm.

Yesterday a giant blast levelled the top of a mountain, part of the 3000-metre peak of Cerro Armazones in Chile.

But this bang is nothing compared to the Big Bang that the telescope the mountain was blasted for will be studying. The European-Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) will be the world's largest optical and infrared telescope and will help astronomers to observe the early Universe, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, in unprecedented detail.

The E-ELT is being built by the European Southern Observatory (ESO), an international collaboration supported by the UK’s Science and Technology Facilities Council. Oxford University scientists are playing a key role in the project: I asked Aprajita Verma, Deputy Project Scientist for the UK E-ELT project at Oxford University's Department of Physics, about what makes the telescope so special and what discoveries it could make…

OxSciBlog: What questions about the Universe will E-ELT investigate?

Aprajita Verma: There are so many! The E-ELT is designed to be a versatile telescope that will answer a huge range of questions in astrophysics and cosmology. Some examples are understanding the first stars and galaxies that formed after the Big Bang, studying extra-solar planets and looking for possible signs of life, and directly measuring the expansion of the Universe.

In extra-solar planets, finding planetary systems like our Solar System but around other stars in the Milky Way is a key driver for the E-ELT. In the last 20 years we've gone from the first discovery of exoplanets to the prospect of directly imaging and studying the atmospheres of exoplanets that are at Earth-like distances from their stars with the E-ELT.

There's a whole host of contemporary astrophysics problems that we can tackle with the power of the E-ELT but perhaps the most fascinating and exciting prospect are the things we just can't predict yet. When we make such an enormous scale change from the currently largest telescopes in operation (8-10m) to a 39m telescope we can expect the unexpected!

OSB: What makes E-ELT unique as an instrument?

AV: The E-ELT will be largest telescope of its kind in the world. The fact that it has a large primary mirror means that we can collect more light, so see deeper into the Universe but it also gives us the ability to observe objects in the Universe in exquisite detail.

The telescope incorporates a system that's called adaptive optics that basically corrects for the blurring caused by atmospheric turbulence. This allows us to get the best possible resolution from the telescope, that's dependent on the size of the mirror, rather than the atmosphere. Space telescopes, like the Hubble Space Telescope [HST], are put up there to get above the atmosphere to avoid this blurring producing some of the most iconic images of the sky we know. But it's simply not feasible to put a mirror of the size of the E-ELT into space, so what the E-ELT can deliver is space quality images but from the ground.

The E-ELT images will in fact be 16 times sharper than the HST! There are several advantages of having a ground-based telescope, we can take advantage of new technologies as they get developed, we can maintain the telescope, we can guarantee a long lifetime (not true of most space telescopes). The E-ELT's baseline operation is at least 30 years but we can expect it to be around taking images and spectra of astronomical objects for several decades to come.

OSB: How are Oxford scientists involved in the project?

AV: Oxford scientists are heavily involved in two main aspects: Instrumentation and science. For the former this means designing and building what can be thought of as the "eyes" of the telescope. The primary mirror collects the light but then this is passed through four further mirrors to a suite of instruments that span different capabilities. These instruments then record the light in different ways.

For example, for the first phase of the telescope there will be two instruments, a camera that takes very high resolution images of the sky called MICADO, and an instrument called HARMONI that is being led by Professor Niranjan Thatte. HARMONI is as an integral field spectrograph or imaging spectrograph. This means that you get an image, but for each pixel in that image you get a spectrum. This is an extremely powerful and versatile instrument, and it's a credit to Professor Thatte and his team that ESO selected their instrument to be available at early light.

We're also involved in other instruments foreseen for the E-ELT, a multi object spectrograph that can take simultaneous spectra of objects in the sky over a wide field (ELT-MOS), and the technologically challenging instrument dedicated to studying extra-solar planets (ELT-PCS).

Several Oxford scientists will be future users of the E-ELT and are therefore very interested in understanding the capabilities of the telescope and how that will aid their research and the UK astronomical community. Professor Isobel Hook and I work with the UK instrument teams and the community to promote and develop the science case for the telescope. Professor Hook has led ESO’s E-ELT Science Working Group that defined the key science cases for the telescope, and the ESO's E-ELT Project Science Team.

OSB: After the ground-breaking what are the next big milestones?

AV: The next big steps for E-ELT are the dome and main structure contracts that are currently out for tender during the next months. Once the tender process has been completed this means that actual construction of the telescope will start.

The contract for the primary mirror production is also a major milestone. The primary mirror of the E-ELT is so large that it can only be constructed by making it in smaller parts. In fact the E-ELT primary mirror is made up of 798 segments, each 1.4m across. Around 1000 segments will be made including spares, so this is a major contract. It's a challenging contract to fulfil as the precision on the smoothness of the mirror surface is very high, it's equivalent to ripples of a few centimetres on the surface of the Atlantic Ocean! To preserve the quality of the primary mirror, 1-3 segments will be removed for cleaning and coating each day!

OSB: What puzzle from your own area of research do you hope E-ELT might solve?

AV: I'm really excited about the prospects for using the E-ELT to push the boundaries of the observable Universe to the first stars and galaxies that formed after the Big Bang. We can only go so far with current ground based facilities and the E-ELT might be able to capture galaxies that were in place in the Universe at only 2-3% of its current age (or about 300 million years after the Big Bang). This will give us tremendous insight on how galaxies first began to form in this very young Universe. We think that about 700 million years later, galaxies like the Milky Way just started their lives and the E-ELT will be able to capture these objects in unprecedented detail and help us understand how our own galaxy might have started its life.

- ‹ previous

- 167 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?