Features

Adventures on the Bookshelf is a popular blog for school students interested in studying French at university. It is run by Oxford's Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages and has received more than a quarter of a million hits in its first year, with readers in more than 100 countries.

In a guest post for Arts Blog, Dr Simon Kemp, whose research interests are in the French novel in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, explains the difficulty of translating the Harry Potter books into French.

'I know from my students that for many people wanting to have a first go at reading a book in a foreign language, translations of J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels are the gateway to reading books in French.

They’re a good place to start: if you’re familiar with the stories already from the books or films in English, then you’ll always have a rough idea what's going on if the language gets tricky, plus it’s always entertaining to find out how a Crumple-Horned Snorkack or a Dirigible Plum comes out in a foreign language.

From the fourth Harry Potter book onwards, once the saga’s French translator, Jean-François Ménard, was most definitely not translating the work of a little-known British children’s author any more, his working routine was the same.

The publisher's paranoia about plot leaks meant that translators were refused advance access to the English original. Ménard's copy arrived on the day of publication of the English-language version. Two months later he would be expected to present the publishers with the French text to be rushed into print for millions of impatient francophone readers.

Every day of those two months would be spent translating J. K. Rowling’s prose, starting at 6 a.m. and finishing at midnight, barring a long lunch-break to refresh his brain and a weekly trip to the physiotherapist to ward off writer's cramp.

Translating Harry Potter presents unusual challenges. What to do with the latiny riddle-language of Rowling’s spells, which allows English-speaking readers to work out that wingardium leviosa implies 'wings' and 'levitation', or that the cruciatus curse will bring excruciating pain?

What to do with the names of people and places, with their hidden jokes and clues? Let’s take a look at a few, so that we can appreciate what Ménard was up against. In the original, Hogwarts school is divided into the four houses, Gryffindor, Ravenclaw, Hufflepuff, and Slytherin.

In Ménard's translation, L'École de Poudlard ('Poux-de-lard', or 'bacon lice') is divided into Gryffondor (‘Gryffon d’or’, or ‘golden griffin’), Serdaigle ('serre d’aigle', or 'eagle talon'), Poufsouffle (which suggests 'à bout de souffle', or 'out of puff') and Serpentard (which contains the word serpent, meaning snake).

Some are quite different, presumably because literal translations of Hogwarts ('verrues de porc') and Ravenclaw ('serre de corbeau') are not as mellifluous, or as funny-sounding, in French as in English.

A little of the subtlety is lost from Slytherin, who are now bluntly linked to snakes, and even the name which stays the same, Gryffindor/Gryffondor, is different, since the French allusion in the original becomes a straightforward label in the translation.

The characters become an exotic mix of French and English names, with Dumbledore, Harry, Hermione and Ron remaining unchanged, but now finding themselves sharing classrooms with Neville Londubat ('long-du-bas', or 'long-in-the-bottom'), Severus Rogue (‘haughty’), and Olivier Dubois, who has to be repatriated from his original identity as Oliver Wood to accommodate a gag about Professor McGonagall needing to 'borrow Wood', which Harry misunderstands as an implement for punishment.

This oddly franco-British establishment becomes odder still with the introduction of an actual French school of witchcraft, Beauxbatons, in the fourth book, leaving us wondering why the French-named students enrolled in Scotland. And talking of French names, Rowling's own liberal use of them gives the translator an extra headache.

Fleur Delacour may sound sophisticated to English ears, but to a French reader it means the rather more ordinary-sounding Yard Flower. Similarly, Voldemort transforms from a figure of fear and mystery to a comic-book villain when his name simply means ‘Deathflight’ (or 'Death-theft') to the reader of the translation.

And it would not escape the notice of the French audience that a surprising number of Rowling's bad guys have French names, such as Malfoy or Lestrange. Rowling perhaps meant them to sound like ancient, aristocratic Anglo-norman families. French readers who missed the implication might have felt a little hurt.

In a project fraught with difficulty, and scattered with no-win situations pitting sound against sense, or humour against consistency, Ménard pulls off a sterling job seven times in succession. I wonder how many French readers realize just how much Harry Potter à l'école des sorciers and its sequels owe, not just to J. K. Rowling, but to J.-F. Ménard as well?'

This blog was originally posted on Adventures on the Bookshelf. Subscribe here to receive updates from the blog.

Over the last few days, media outlets from Fox News to Russia Today have reported on a new book claiming to have uncovered a previously censored ‘fifth gospel’ which they say reveals that Jesus married Mary Magdalene and they had two children. In The Lost Gospel, which is published today, Professor Barrie Wilson and writer Simcha Jacobovic claim to have translated a manuscript dating from around 600 CE and written in Syriac, a dialect of the Aramaic language spoken by Jesus.

Jonathon Wright, a DPhil student in Oxford University’s Oriental Institute, has studied the Syriac version of the ancient story of Joseph and Aseneth, on which these claims are based. He assesses the sensational claims in a guest post for Arts Blog and concludes that they are not at all credible.

'The story referred to is commonly called Joseph and Aseneth. It was originally written in Greek and translated into a number of ancient languages. The story deals with Genesis 41.45, which says Pharaoh gave Aseneth, the daughter of a pagan priest, to Joseph as a wife.

It seems Jews and Christians worried about how Joseph could marry a presumably idol-worshipping woman, especially as the children were the ancestors of two tribes of Israel. Joseph and Aseneth tells us that Aseneth was converted to worshipping God through repentance and fasting after meeting Joseph.

Let us consider two of the sensationalist claims made in the book. First, “the story is about Jesus.” For early Christians, their Bible was the same as that of Jews. Important figures in the Old Testament came to be seen as types of Jesus. Christians saw in a popular figure like Joseph some elements of Jesus’ ministry.

The book's authors claim the story is about Jesus all along, but there is no evidence for this in the text, or any of the 90 or more manuscripts still existing today- indeed in the Armenian tradition it is often in the Old Testament. Joseph in the story does not do anything we associate with Jesus. The story was probably often copied because it was not controversial and because Christian beliefs about repentance and conversion were portrayed in an apparently Jewish story.

Secondly, “the story was censored.” A good conspiracy theory always helps improvable claims. In the oldest Syriac manuscript, the end of a letter from the translator and the first chapter is lost. It appears that this letter was just about to provide some interpretation about the story. The authors of this book suggest it was torn out because it said that Joseph really was Jesus.

We can strongly doubt this! It is much more likely that the page was lost through wear. There are several other places this has happened in the manuscript. The story was copied into another Syriac manuscript in the middle ages, and this included the opening chapter, so the page still existed hundreds of years after it was written. This later manuscript has many works of the Church Fathers which would absolutely dispute that Jesus was ever married. Probably, the copyist thought the message of the work was clear enough and not controversial.

The one good aspect of this book is that hopefully more students will want to learn Syriac and discover the wealth of literature which extends to the present day. With the war in Syria and Iraq at the moment, a poignant fact is that many truly remarkable stories and histories have probably been lost forever as a result of Islamic State, not to mention the human cost to a culture with roots stretching back to shortly after the time of Jesus himself.'

The Lost Gospel by Simcha Jacobovici and Barrie Wilson was published on Wednesday 12 November by Pegasus Books.

Sunday 9 November was the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. The event was marked by thousands of illuminated balloons installed along the former course of the wall. On Sunday evening, the balloons were released into the sky.

'It's a significant anniversary because it means a generation has now come to adulthood with no memory of living under the GDR (East Germany),’ says Karen Leeder, Professor of Modern German Literature in Oxford’s Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages.

One might expect that people’s connection with the GDR would be falling as time passes, but Professor Leeder says more young people have connected with the culture of the GDR in recent years. She says: 'Nostalgia for the GDR is becoming more prevalent.

'GDR-branded goods such as Spreewald gherkins are popular and young people have re-established the Jugendweihe celebrations (a secular coming of age ceremony practised by 14 year olds), which were common under the GDR, to mark the end of their exams. Young writers who were children when the Wall came down are writing books which draw on their connection to the GDR.

'This is also reflected in politics. Die Linke, the left-wing party which descends from the former socialist unity party under the GDR, received 30% of the vote in Berlin in the last election (and 45% in the Eastern part) including a strong youth vote. At demonstrations you see a curious combination of the old guard who lived under the GDR and young people who were born in the 90s.'

Professor Leeder says disaffection with modern Germany is also increasing among older people who lived in East Berlin. 'Every so often there are questionnaires in which people are asked if they preferred life under the GDR and a large percentage still say yes,' she says. 'A lot of people continue to live a segregated life, staying in their own areas and rarely venturing into the west of the city.'

Professor Leeder says this increasing disaffection is partly due to the struggles of former-GDR areas in recent decades, which have suffered from high unemployment, low household income and a 'brain drain' of young qualified people moving to the west. But she argues that a key reason is that the reality of life under the GDR is being written out of the official narrative of post-war Germany.

'There is a divide between this local and regional connection to the GDR on the one hand, and the official narrative of modern Germany on the other,' says Professor Leeder. 'Germany and its political institutions present themselves today as having totally obliterated the GDR.

'The Wall is gone and the buildings are gone. Last weekend’s ceremony featured illuminated balloons along the course of the Wall to demonstrate that Germany has left the dark and come into the light.

'There were of course terrible things about the GDR but lots of people grew up, raised families and spent half of their lives in East Germany and they feel that the state does not recognise this experience as legitimate. They have had their history packaged, commodified and rendered back to them.

People from the former west run the GDR museums and encourage tourists to buy pieces of the Wall, Soviet-style hats and Ampelman figures which were used on traffic lights in East Berlin. So it is no surprise that there is a divide in the politics and culture of Germany.'

Given Germany's relative economic strength and political clout in Europe, this diagnosis might surprise some people. Professor Leeder explains: 'Hosting the World Cup in 2006 allowed Germany the opportunity to find a way to be nationalistic without seeming aggressive, and the country has developed a much more dominant role in Europe.

'But while the nation has become outwardly more confident, inwardly it is still very much coming to terms with its split identity. With the drive to present itself as a united, central political player, there has been a strong urge to gloss over a lot of the ambiguities of modern Germany.'

Professor Leeder says this approach is not the way to unite Germany. She says: 'I am currently writing a book called ‘Spectres of the GDR’ and one of the fascinating things is that since 1990, ghosts and spectres from Germany’s past have become very prevalent in art, film, literature and photography.

'As the past is repressed, it comes back in various forms as a threat or a disturbance. Germany needs to address the reality of its history before it can lay these ghosts to rest.'

Spectres of the GDR will be published by Duke University Press in 2015.

An Oxford academic is working with an American theatre company to test her research into how actors would have rehearsed in the time of Shakespeare.

In a book published in 2000, Tiffany Stern presented new information about the way plays would have been rehearsed in Shakespeare’s time. Since then, Professor Stern of the Faculty of English Language and Literature has been working with a theatre company which is following this model.

'A lot of people have investigated how actors performed in Shakespeare’s time, but not how they rehearsed,' Professor Stern said. 'Companies put on different plays every day because London was too small to sustain audiences for the same play. They might put on forty different plays in a season so there is no way they could rehearse each play for four weeks the way actors do today.

'Surviving parts from actors of the time reveal that they were given only their own speeches and their cues, so they would have learned their lines without knowing the full, detailed picture of the play. This makes a lot of sense because paper and scribes were expensive and there was no copyright so, if a full manuscript of your play fell into the wrong hands, someone else could perform your play.'

Having published this research, Professor Stern then learned that some theatre companies were already adopting it. She was contacted directly by the American Shakespeare Centre in Staunton, Virginia, USA.

Professor Stern explains: 'I went to talk to the ASC and meet the actors and since then we have struck up a mutually beneficial relationship. It’s given me a laboratory to test ideas about how actors would have rehearsed and performed in Shakespeare's time.

'I was interested in the texts actors read aloud on stage to save them having to learn some lines – for example, when they read out a fictional letter. I asked the actors in Stanton about this and they tried it out and came back to me to suggest that actors would have written letters out themselves.

'They explained it is hard to read alien handwriting on stage for the first time -- while writing the words in advance would help them to approximate what was said if they were given the wrong document on the night! I then found evidence that this was the case.'

She added: 'They also came up with a number of other ways that actors could have saved themselves from rote learning all their lines, for example using hats and other props to secrete text.'

Professor Stern said this model of producing plays may be beneficial for the future of performances for small Shakespeare companies. She said: 'I think we will see more and more companies start to put on plays in this fashion, partly because it saves their paying for a director, but also because it gives their actors a lot more autonomy and responsibility.

There are also artistic advantages to an actor only learning their own part. Professor Stern said: 'If your part is a humorous one, or you have a comic line, then you will act comically. But if a modern actor is playing a humorous role within a tragedy, he or she is likely to act according to the mood of the play.

'If you perform having largely rehearsed just your own part, you are likely to deliver a much richer and more varied performance of the play.'

Professor Stern added: 'It also makes us look at Shakespeare's writing in a new way. He was conceiving plays not only as a full narrative arc, but as separate strips of text with their own internal logic.'

This weekend is the last chance to see the Tutankhamun exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum. Almost 35,000 people have visited the exhibition so far, and it has been the most popular special exhibition for school groups in the history of the Museum.

The exhibition draws extensively from archival material about the discovery of the tomb, which is held by the Griffith Institute, part of the Faculty of Oriental Studies. Cat Warsi and Elizabeth Fleming of the Griffith Institute have given Arts Blog an interview about the exhibition.

The exhibition has shown the Griffith Institute to be the world’s main centre of archive material relating to the tomb of Tutankhamun. How did this come about?

Cat Warsi: About 15 years ago the then Keeper of the Griffith Institute Archive, Dr Jaromir Malek, made the decision to start an ambitious project to publish online all material housed within the Institute’s archive relating to the excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun. The excavation records, created by Howard Carter and his team from 1922 to 1932, were given to the Institute by Carter’s niece, Phyllis Walker after Carter’s death in 1939.

Carter had always planned to publish a full scientific account of all the 5398 objects found in the tomb but died before he could complete it. Due to many factors, not least the outbreak of WWII, this task was not taken on by the subsequent generations of Egyptologists – new material is constantly being discovered in Egypt and there may have been a certain amount of trepidation amongst scholars to take on objects that are so well known; coupled with the understandable security measures in place to access some of the world’s most valuable works of art.

Dr Malek felt it was an unacceptable state of affairs that so little of Carter’s Tutankhamun records had been studied and hoped that by digitising thousands of notes, photographs and plans and making them freely available online, academics could incorporate the study of objects from the tomb into their research and so continue the work Carter started 80 year ago. It took many years to completely scan, catalogue and transcribe all the material, but now that it is fully accessible to everyone we are starting to see results.

Objects from the tomb are slowly being published, with more and more Griffith Institute material being citied in research and academics requesting copies of documents or visiting Oxford to work with the originals. We are currently aware of 20 academics working on objects from the tomb, with many nearing completion within the next five years. Though it may surprise people to learn that perhaps the most famous object of all, the gold mask, has never been comprehensively studied and published; this is surely the real ‘curse of Tutankhamun’.

What do you hope will be the exhibition’s legacy?

CW: The Griffith Institute is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year but, in partnership with the Ashmolean Museum, this is our first ever public exhibition. Whilst Egyptologists may know of our existence, this has given us a real public platform to engage with people and showcase some of the ‘wonderful things’ we have in our Archive. It’s given us the opportunity (in collaboration with the British Museum) to produce learning resources for families and schools which will live on and grow after the exhibition closes.

Elizabeth Fleming: Whilst sourcing archive material for the exhibition we have become aware of the ‘gap’ within our Tutankhamun Archive which documents the huge global impact the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun had on the world, from the moment of discovery in November 1922 which has continued to the present day. As a consequence the Archive is actively collecting and preserving documents such as original newspaper reports, Tutankhamun/ancient Egyptian themed advertisements, sheet music, cigarette cards, period photographs and costume jewellery.

CW: In amongst all the myths, theories and curse stories surrounding the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun we hope we’ve given the public thought-provoking facts and information from which they can decide what to believe and continue researching if we’ve sparked their interest. If we've been able to communicate just a fraction of the love and excitement we have for our subject then the exhibition will have been a success.

Do you hope it encourages young people to consider studying Egyptology and archaeology?

CW: One of the first objects visitors see when entering the exhibition is a beautiful watercolour by Howard Carter painted many years before the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Having grown up and been home-schooled in a small village in Norfolk, Carter first travelled to Egypt when he was just 17 in order to draw and paint scenes in tombs and temples.

We hope young people will be inspired by Carter’s story but that it also shows the patience, passion and dedication needed to pursue such a career. Little has changed since the 1920’s in as much as the hours are long, the jobs are few and discoveries may be a long time coming – Carter didn’t discover Tutankhamun’s tomb until he was 48!

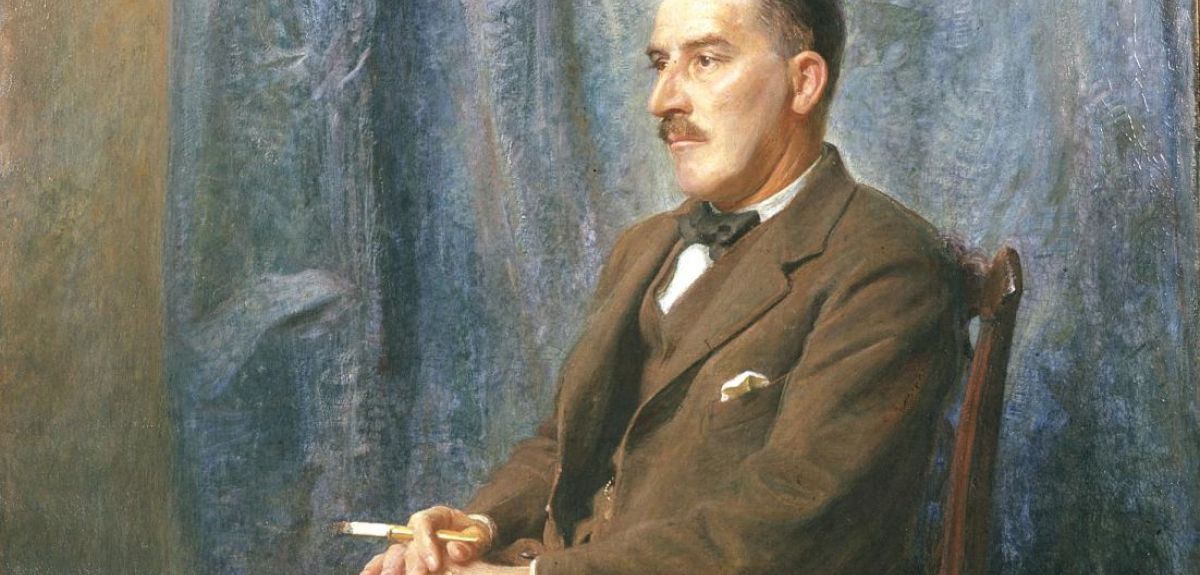

EF: The last object in the exhibition is another painting, this time the subject is Howard Carter himself. This portrait painted by Howard’s brother William, was created not long after the discovery of the tomb, he is shown seated staring into the middle distance which allows the viewer to imagine that Howard Carter is reflecting on his great accomplishment.

The curators of the exhibition invite young exhibition visitors to contemplate Howard Carter’s great achievement too, and if they are contemplating a career in Egyptology, to consider continuing Carter’s work on publishing all of the objects found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, which even now, 92 years after the discovery, leaves 70% of the tomb’s contents not properly studied and published.

How has the feedback been?

CW: We’ve been absolutely delighted with the many reviews the exhibition has received; people seem to have understood the narrative we were trying to get across and our motivations in staging ‘yet another’ exhibition on Tutankhamun, albeit from a very different angle. We all have our favourite items we hope our audience has discovered, but one of the most popular amongst reviewers seems to have been a wonderfully illustrated item of Carter’s ‘fan mail’ written by a six year old Irish boy wishing he ‘was an Egyptolisty’ like Carter. Of course feedback also highlights things we could have done better and although we may not have another exhibition in the immediate future we can apply constructive comments to archive material published on our ever expanding website.

Has the exhibition led to any unexpected results?

CW: As hoped, the exhibition has highlighted our existence amongst non-specialists and we have already received two donations of archive material from a members of the public as a consequence. We’ve received more enquiries generally concerning Tutankhamun – along with the many other benefits we hope this exhibition has made us more approachable.

The exhibition has also given us the opportunity to get in touch with old friends, including the grandson of Arthur Mace, a member of Carter’s team, who very kindly donated some family papers to the Archive.

One of our aims for the exhibition was to highlight Carter’s early work in Egypt as an artist, a passion that he sustained throughout his life but something many are not aware of. While visiting us Mace’s descendent told us a fantastic story passed on by his grandfather, that whenever Carter (a man notorious for his bad temper) had a real bee in his bonnet Mace would send him out of the tomb, telling him to go and paint in order to calm down.

EF: As many of the contemporary records for the discovery and excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun are black and white, visitors have a unique opportunity to view the treasures of the tomb without the ‘distraction’ of gold. As a consequence, we’ve been asked many more questions about the less familiar material from the tomb during tours of the exhibition.

A recurring question from visitors who were especially intrigued by a line of boat oars carefully placed in antiquity along the floor next to Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus, the oars ritualistically represented the boat that the King would use on his journey through the Underworld where he would have to face many obstacles and challenges before he was allowed to be reborn in the Afterlife. This is just one example of visitors being able to engage with the hidden gem buried with Tutankhamun, often overshadowed by the more spectacular gold items from the tomb, such as the iconic solid gold mask of Tutankhamun.

The exhibition will remain open until Sunday 2 November. A special 'Live Friday' event will be held this evening (31 October) from 7.30pm-10pm. Admission is free.

If you have been inspired by the exhibition to consider studying Ancient Egypt, Oxford University is a leading centre for undergraduate and postgraduate study in the field. More information is available here.

- ‹ previous

- 159 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?