Features

Two new exhibitions have opened at the Ashmolean Museum.

Love Bites: Caricatures by James Gillray and Great British Drawings will be on display until 21 June and 31 August respectively.

Love Bites marks the 200th anniversary of the death of British caricaturist James Gillray. Visitors can see more than 60 of Gillray’s finest caricatures from the collection of New College, Oxford.

'We are accustomed to seeing caricatures that divide the world along political and personal lines,’ says Professor Todd Porterfield, exhibition curator.

'In this exhibition I hope to emphasise a previously under-explored theme in James Gillray’s work: love, friendship and alliances; and by doing so to provoke fresh insights into his work and to show that Gillray was a substantial figure of his time and an enduringly great artist.'

Great British Drawings showcases the Ashmolean’s collection of British drawings and watercolours, which is considered one of the most important in the world. The exhibition comprises more than 100 words by some of the country’s greatest artists and many of them are on display for the first time.

The exhibition includes work from Flemish artists working in Britain in the sixteenth and seventh centuries and experiments in modernism instigated on the Continent and enthusiastically taken up by the British after the First World War.

'The exhibition of Great British Drawings can only scratch the surface of the extraordinary riches of the Ashmolean’s collections,' says Colin Harrison, Senior Curator of European Art at the Ashmolean Museum.

'It will provide the visitor with an unparalleled opportunity to explore the amazing variety of drawing in Britain, from the rapid sketch in pencil or pen, to the most highly wrought watercolour.'

Ashmolean staff hanging a James Gillray caricature

Ashmolean staff hanging a James Gillray caricatureAshmolean Museum

The remains of Richard III were reinterred at Leicester Cathedral today (26 March 2015).

Dr Alexandra Buckle, an expert in medieval music at Oxford University, has been on the Liturgy Committee for the Reinterment of King Richard III for nearly two years, after finding the only known manuscript to document what a medieval reburial service involved.

Over the last two years, Dr Buckle has been working on the context of medieval reburials, looking at why they happened, who organised them and who received them. She has managed to compile a long list of the great, the good and the not-so-good of the 1400s, involving most kings, dukes and earls.

She said: 'Medieval reburials were far more common than I envisaged. They happened for many reasons – this was an age of active warfare – many who fell in battle were buried cloe to where they fell, only to be moved by family members to a place with family associations 10-30 years later.

'Other reasons include political, status and, always, a desire to keep the dead in the memory of the living. Richard III was involved in two reburial ceremonies (for his father, Richard, duke of York and for Henry VI) so he would have not been unfamiliar with the medieval document of reburial I found, which dates from his life time.'

Dr Buckle's discovery has formed the basis for the ceremony in Leicester Cathedral.

She said: ' The manuscript I found in the British Library has really guided the process: the opening and closing prayers are taken from this, as well as much in between.

'The manuscript includes two unique prayers, not known to survive in any other liturgy, and these have become a real feature of the service. They draw on passages in the bible which feature bones – the famous ‘dry bones’ passage from Ezekiel and the carrying of Joseph’s bones from Egypt to Canaan.

'The document has also influenced the music – although the medieval chant of this service will not be the only music heard, the same items of music will be used. For example, where the document asks for Psalm 150, the chant will not be used but a modern setting of this will be heard instead, in this case a setting, which has been revised for this occasion.

'The manuscript called for a lengthy service, running over two days so some of the material has had to be cut, namely the prayers which draw heavily on the doctrine of Purgatory and are, therefore, not appropriate in a modern, Church of England service. In addition, some modern elements (such as hymns, commissions and The National Anthem) have had to be added to make this service intelligible to the congregation and those watching the broadcast at home but much remains from the medieval rite.'

Dr Buckle said the ceremony gives a dignity to Richard III's memory that would have been missing from his original burial.

'When I started work on this manuscript, I never envisaged it would influence a service of national importance and that some of the prayers I unearthed would end up in the mouth of The Archbishop of Canterbury. The team at Leicester have had a hard task but I think they have managed to blend the medieval and modern sensitively. Richard III’s funeral was notoriously plain and hasty: he did not have a coffin, his grave was too small and he only had the most basic of funerary masses. The overriding concern of the team at Leicester has been to bury Richard, this time around, with dignity and honour, and it has been very special to be involved with this process.'

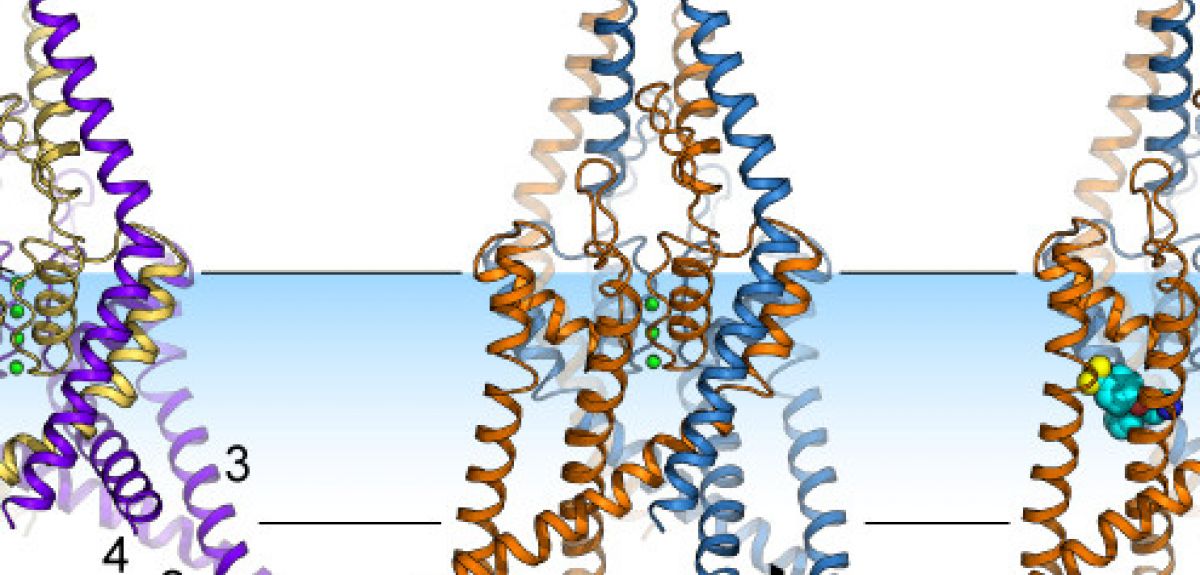

The electrical impulse that powers the workings of the brain and the heart begins with charged particles passing through cellular structures known as ion channels. Using the same technique used to decode the structure of DNA, an Oxford University team has been able to catch snapshots of an ion channel in action. Their results, published in Science earlier this month, help explain how neurons respond to a variety of stimuli, from drugs to touch.

I talked to the lead authors, Professor Liz Carpenter from the Structural Genomics Consortium and Professor Stephen Tucker from the Department of Physics, about why it Oxford is a particularly good place to study ion channels.

OxSciBlog: What are ion channels and why are they important?

Stephen Tucker: Ion channels are literally holes in the cell membrane, and they allow electrically charged particles ('ions') to move from one side of the cell membrane to the other. This is the process responsible for conducting the electrical signal via which the brain and the heart work.

So ion channels are important because they control neuron excitability, which in turn controls how different parts of our bodies talk to each other and how we sense the external world.

Liz Carpenter: Cell membranes are what separate the inside of cells from the outside, and ion channels sit right in the cell membrane. When a nerve fires a burst of electricity, charged particles flow through ion channels, acting like a current. This current then triggers other channel opening, and this is how electrical activity flows down the nerve cell.

OSB: You've got many collaborators from pharmaceutical companies as well: why are these cellular structures of particular interest for people interested in drug development?ST: They're many, many different kinds of ion channels, letting in different kinds of charged particles. We're specifically looking at an ion channel called TREK-2 that let in charged potassium ions, and while you find these channels all over the heart and the brain, they're especially concentrated in nerves that sense pain.

And if we can figure out a way to activate these channels, to keep them open, then we can actually silence the cascade of electrical activity through which neurons communicate. This could potentially block the pain signal from getting to the brain.

OSB: So how are these channels activated?

LC: Originally, people thought that these channels just let in charged potassium ions. But since then, researchers have found that they are activated by stretching the cell membrane, by temperature changes, and by a whole range of pharmaceutical compounds. We still don't know how all these ways of modifying the activity of these channels affects the activity of cells in the brain. What we do know is that in a test-tube, you add some drugs to these channels and they open, and other drugs make them close.

The problem was that before our study, the picture that we had for these ion channels was a little square blob: we didn't actually know what their structure looks like, or how they open and close.

So my group has been studying all possible human ion channels (they are 240 of them!). These proteins are very difficult to crystallize (which you need to do in order to study their structure), but the family of ion channels that TREK-2 belongs to are particularly well-behaved. Not only did we manage to crystallize the TREK-2 channel, but just by chance, we actually got crystals of two different states of the channel: we saw a structure that was stretched, and then another structure that was much less stretched.

OSB: What does the structure of these TREK-2 channels look like?

LC: This channel has two protein chains, with each chain made up of a few thousand atoms. Each chain folds up into a series of helices and loops, which come together to form a folded structure with a pore at the centre. This pore acts as a filter: the oxygen atoms in the pore are lined up in such a way that they can only bind potassium ions, so that is the only thing that can pass through these channels.

When we looked at the crystal structure of these ion channels, we found that the helices could either move down into the inside of the cell, or move up, into the cell membrane. This movement is somehow controlling the flow of ions past the oxygen atoms and through these channels.

OSB: How did you discover this structure?

LC: We have to start by persuading a 'reporter' line of insect cells to produce the protein that we're interested in studying: we splice the gene for the specific protein that we're interested in into an insect virus, which then infects the cells, causing them to make large amounts of the protein.

The next problem we have is that these ion channel proteins are water-repellent (hydrophobic) where they interact with the cell membrane, and water-attracting (hydrophilic) where the interact with the inside and outside of the cells. So we can't just pull these ion channels out of their cell membranes by dissolving them in water.

So we add detergent, which is good at dissolving hydrophobic and hydrophilic molecules: it's not quite washing up liquid that we’re using, but it's not far off!

Then we try use a variety of different reagents to try and persuade all these ion channels to line up in orderly arrays next to each other: to make crystals, in other words. Whether this works or not is very much a matter of luck, I'm afraid!

OSB: Why do you need to crystallize these molecules in order to study them?

LC: We work out the structure of molecules from the diffraction pattern that are produced by passing a beam of X-rays (at the Diamond light source in Harwell) through the material: single molecules by themselves aren't big enough to produce a strong enough diffraction pattern that we can study.

But if we line up each of the molecules to make a crystal, the crystal acts as an amplifier, producing a clear diffraction pattern. We rotated the crystal within the X-ray beam to get different diffraction patterns, and then we worked back from the diffraction patterns to figure out where each individual atom sits in the ion channel.

This is the same technique that was used to work out the structure of DNA, another complex protein molecule. But we're finally getting to the point that we can use this method to look at the structure of human proteins, which have been particularly hard to work with: they’re hard to express in reporter cell lines (if we get half a milligram of protein, we’re very happy!), and hard to crystallize.

OSB: What was the next step, once you had the structure worked out?

ST: We were lucky enough to solve more than one protein structure. But we still didn't know which structure corresponded to the open version of the channel and which to the closed version: just looking at two structures, you can't tell which one was open and which was closed, since it looked like ions could get through both forms of the channel.

So we took advantage of the fact that some drugs, such as Prozac, are known to only bind to the TREK-2 channel when it is closed. So when Liz managed to get a crystal of TREK-2 with Prozac bound to it, we knew that this version of TREK-2 had its 'pore' closed, not allowing potassium to travel through it.

LC: We also wanted to track exactly where Prozac binds to the channel. But Prozac itself doesn't show up in the diffraction patterns that we're using, so we used another trick: we attached a molecule of Bromine to the Prozac. Bromine lights up nicely in the diffraction pattern, and lets us see exactly where the Prozac is attaching itself to TREK-2.

So we really needed all sorts of different expertise in order to these experiments: my experience is in decoding protein structures, and Stephen's interest is ion channel function. But we needed the help of our colleagues from the Chemistry Department to do the Bromine tagging experiment, and colleagues at a pharmaceutical company supplied us with the drugs that we used in the experiment.

ST: In Oxford, we're lucky enough to have a huge consortium of people who work on ion channels (the OXION consortium), and I think this study demonstrates why Oxford has become a major international centre for this kind of work. For example, the two images that we got were frozen snapshots, but we think that this channel is likely to exist in many states, rather than just two. Computational modelling from other colleagues (Professor Mark Sansom in the Department of Biochemistry) was also essential to give us an idea of how the protein might actually move in a cell membrane.

OSB: What sort of future work are you planning?

ST: The drug that we looked at, Prozac, binds to a 'window' in the channel that only exists in its closed state. We'd like to look at how some other drugs bind to TREK-2, and we need very high-resolution 'pictures' of the channel in order to do this.

LC: There are other ion channels related to TREK-2 that we'd like to look at: one of them, TRESK, has been linked to migraines for example. We'd like to work out the structure of these channels, especially since many of them have been linked genetically to diseases. We're also trying to get more uniform crystals to increase the resolution of the structure we get.

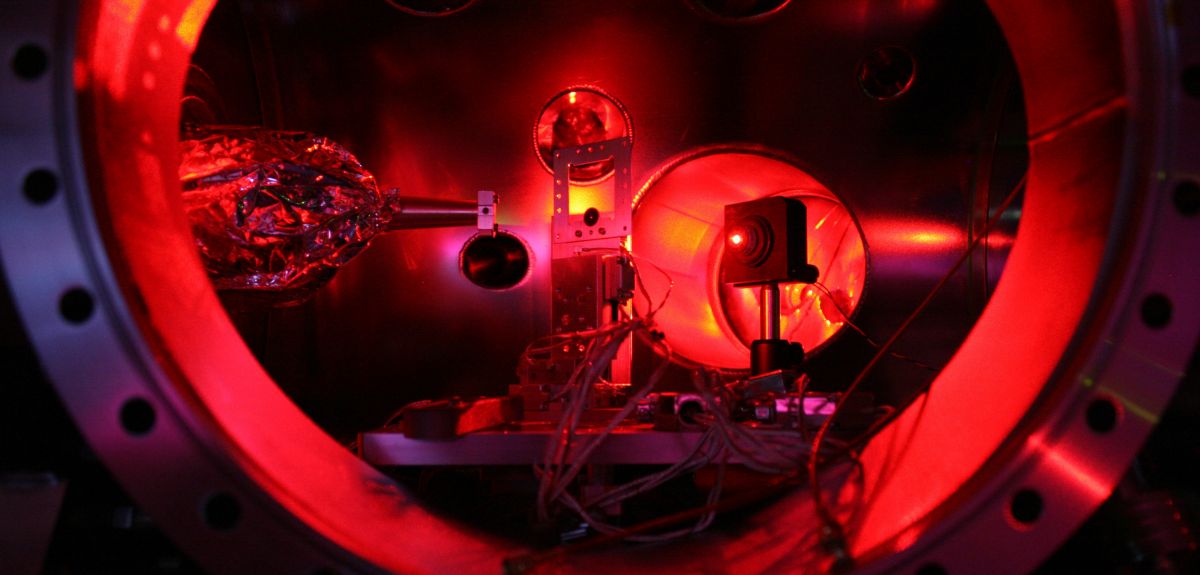

We're also going to use a fantastic new device called the LINAC Coherent Light Source (LCLS) in Stanford: it is about a billion times more powerful that the light source we've used previously, which means that laser pulses hit the sample hundreds of times every second. What we're going to do here is fire a slurry of small crystals through the LCLS beam. The crystals explode as they hit the beam, but we get our data before the atoms within the crystal have time to move apart. The data we get from the LCLS is going to much higher-resolution, and it will allow us to study ion channels that don’t crystallize into large crystals.

By recreating the extreme conditions similar to those found half-way into the Sun in a thin metal foil, Oxford University researchers have captured crucial information about how electrons and ions interact in a unique state of matter: hot, dense plasma. Their snapshot of the fraction of a trillionth of a second during which these extreme conditions existed during the experiment found that previous theoretical models used to inform how quickly atoms ionize and heat up in a dense plasma were off by a factor of three.

I caught up with Dr Sam Vinko, the lead researcher of the study published in Nature Communications, and I talked to him about how to recreate stellar conditions in a lab in California.

OxfordSciBlog: Your study investigates conditions during a plasma; what is this state, and why is it important to look at it?

Sam Vinko: A plasma is a collection of electrically charged particles: a flame is a common example, but plasmas are ubiquitous – they are the most common state of matter in the visible Universe. For example, our Sun in made of plasma, a soup of electrons and ions at high temperatures and densities.

Using intense X-rays, we've been looking at how to recreate extreme states of matter, conditions similar to those found half-way towards the centre of the Sun, in a lab. We managed to create a plasma at a density typical of a solid, but heated to several million degrees centigrade.

We're interested in these sort of extreme states of matter for many reasons; they are important to understand how matter behaves in the cores of large planets, various types of stars and other astrophysical phenomena, in intense laser-matter interactions, and also for inertial confinement fusion (ICF) research.

Inertial confinement fusion is a process where hydrogen isotopes are merged together to create helium, a neutron and quite a bit of energy, in a way similar to what happens in the core of stars. It's a potentially very promising source of energy for the future, but we still need a better understanding of the physics of matter in extreme conditions to get it to work controllably in a lab.

OSB: How did you create this hot, dense plasma?

SV: We created this plasma state by exposing a very thin sheet of aluminium foil to X-ray laser pulses produced by the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) in Stanford, California. This is the most powerful X-ray source every made, and the X-rays are focused on a spot 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair. The end result is of course a hole in the foil, as the ions quickly heat up and the foil explodes.

But atoms and ions have some, albeit small, mass. Because of this mass, they have some inertia. And this inertia means that it takes some amount of time for the ions to move and for the material to actually explode. The trick here is that if you can do all your physics before this explosion happens, you’ve got what is called 'inertial confinement': the plasma is being held together by the inertia of its constituent atoms and ions.

So we created a hot and dense plasma by taking advantage of this inertial confinement: we dumped a large amount of energy very, very quickly onto a solid target, in the fraction of the trillionth of a second, before the material has had a chance to explode. This is the point where we take all our measurements: before the material blows up.

OSB: How long did you experiment last then?

SV: Our entire experiment is over in about 50 femtoseconds (a femtosecond is a quadrillionth of a second). This is an unimaginably short amount of time, but to give you a sense of how short it is: there are more femtoseconds in a single minute than there have been minutes since the beginning of the Universe!

OSB: What do you measure during this short time?

SV: We do spectroscopy: we record and then analyse the light emitted during the experiment to find clues about the underlying processes. One key problem is how to limit this analysis only to the radiation that is emitted in the first 50 femtoseconds of the experiment.

The trick we use to get around this problem takes advantage of the fact that the inner-most electrons orbiting the nucleus remain tightly bound, even in the hot plasma conditions we create. They are only knocked lose by the high-energy X-rays we use. So the 'fingerprints' of these innermost electrons are only visible when the X-ray beam is on, which in turn allows us to observe the sort of extreme conditions you’d find ordinarily only inside stars.

We analysed these spectral 'fingerprints' to track a specific property that we were interested in: collisional ionization.

OSB: What is collisional ionization?

SV: Electrons which have been knocked out of their orbits (e.g., by the high-intensity X-ray pulse that we used) collide with other electrons inside atoms and ions, in turn knocking them out from their orbits: this is known as (electron) collisional ionization.

The rate at which collisional ionization takes place in a material is very dependent on its density: if you have a gas, it's more likely that a free electron will just fly off without bumping into anything else. In a more dense material, it's more likely to bump into another electron.

But the rate at which this collisional ionization happens has never been measured in a dense plasma before, in part because it is so very quick – on average it takes place in less than a femtosecond!

OSB: Why is it important to measure these rates?

SV: Collisional rates are essential to model and understand how a dense plasma (such as that found in an astrophysical object or in an inertial confinement fusion experiment) is created, and how it heats, ionizes and equilibrates.

These collisional ionization rates have previously been either calculated from theory or extrapolated from measurements in very diluted systems, but have never been measured directly in a dense system. We’ve now found a way to measure these rates for a hot, dense plasma.

OSB: What did you find?

SV: Firstly, we've shown that it is possible to measure very, very short-lived events, by tracking them with respect to other short-lived events that have a clear 'fingerprint'. The trick was to use Auger decay (a very fast process where electrons inside an atom or ion are reshuffled to fill a hole in a deep state) as an ultra-fast clock to time a collisional event in a single ion – a process that takes on average less than a million-billionth (quadrillionth) of a second to happen.

By measuring these ultra-fast events, we've found that the collisional rates are actually much higher than had been assumed previously: it’s not a small amount either, since the rates we find are more than three times faster. So the ionization process seems to be a lot more efficient than people had thought previously.

We're hoping that this is the first of many experiments aimed at replacing untested models with quantitative, experimentally measured values. The fact that current models don't quite work in many conditions isn't really a surprise, given their reliance on extrapolations and unverified assumptions. Excitingly, we now have a method that can provide the experimental data to plug in the gaps.

This week, Oxford students will investigate ethical puzzles - from the everyday to the extraordinary - through a practical lens.

The Oxford Uehiro Prize in Practical Ethics has been organised by the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics in Oxford University’s Faculty of Philosophy. The four finalists in the competition will present their cases in an event on Thursday 12 March which is open to the public.

Professor Julian Savulescu, director of the Centre, said: 'This competition aims to bring students from across Oxford together to think about an issue in practical ethics, drawing on their own expertise whether that is philosophy, politics, theology, or even science or medicine.

'Whatever career our students choose, a workforce which is trained to identify ethical problems, think logically about how and why they occur, and find an ethical solution will be a positive step forward for the future.'

The four philosophy students have given Arts Blog a preview of their arguments.

Should I stop playing music in my room because my neighbour can hear it through the wall?

According to Miles Unterreiner, a graduate student at St John's College, we all engage with practical ethics, whether we're aware of it or not.

'Supposing my displeased neighbour wants me to stop listening to music because she can hear it through the wall,' he said.

'I think I have a right to play music in my own room. Should she buy earplugs, or am I obligated to buy headphones?

This is a small and relatively insignificant example, one of the many questions about right and wrong that we ask ourselves every day.

How many lives can you save?

'If we care about the well-being of others, we should try to improve the lives of as many people as possible by as much as possible,’ said Dillon Bowen of Pembroke College, who has researched the most effective ways to give to charity.

'Now, when you first hear this, it seems like a strikingly obvious idea. If I donate £100 to charity, and I have the choice between donating to a charity which can save two children from starvation, or one which can save 20 children, I ought to choose the latter.

'But these sorts of economic questions don't often enter into people's minds when they donate money. People see someone in need, feel a strong visceral desire to help, and donate to the cause. End of moral calculus.

'But when it comes to morality, we need to think more reasonably. It's good that we want to help people, but bad that the way we go about doing it is so ineffective. We need to retain the altruistic intuition to help others, but use our reason to make sure we're helping others effectively.'

How should you live if you care about animals?

Xav Cohen, of Balliol College, is vegan because he cares about the harm that comes to animals from humans eating meat and using animal products. But it's hard to say how vegans should behave if they really want to minimise harm to animals: should they try to convince as many people as possible to adopt a fully vegan lifestyle?

'I found that vegans should really be looking to build a broad and accessible social movement which allows people to reduce their consumption of animal products, rather than condemning anything that isn't full veganism,' he said.

'This will lead to less harm to animals overall. What's needed is a popular label or movement which is plural and accepting, with the only requirement that we do more to reduce harm to animals.'

Should people be allowed to have breast implant surgery if it will harm them?

'Some would argue that a woman’s decision to have breast implants is morally unproblematic, as long as the woman is not coerced into having the surgery,' said Jessica Laimann, also of Balliol College. 'But if women believe that their success, self-worth, and even their careers depend on their appearance, is this still the case? Arguably, breast implant surgery is significantly harmful.'

So should we prohibit this kind of surgery in order to protect people from harming themselves?

'I immediately feel uneasy about the idea of prohibition. There is something deeply problematic about letting a society create people with the desire to inflict harm on themselves, and then trying to solve the problem by prohibiting these people from acting on that desire.

'Prohibiting breast implant surgery would put the lion’s share of the costs of changing harmful social norms on the people who already suffer most from them. Instead, we need to forcefully address the circumstances that make them willing to harm themselves in the first place.'

- ‹ previous

- 152 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?