Features

200 years ago William Smith published the first geological map of England and Wales. A new exhibition at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History tells the story of the life of Smith, the 'father of geology'.

The exhibition is called 'Handwritten in Stone: How William Smith and his maps changed geology', and runs from this Friday (9 October) to 31 January 2016.

The Museum holds the largest archive of Smith material in the world and many of its treasures will be shown in the exhibition. The map will be shown alongside Smith’s personal papers, drawings, publications and other maps, in addition to fossil material from the Museum's collections.

Visitors can also see the oldest geological map in the world – a map of Bath drawn in 1799 by Smith.

Smith was born in Oxfordshire and he conceived his geological theories and created maps single-handedly. His story was made famous with the publication of Simon Winchester's 'The Map that Changed the World' in 2001. Mr Winchester will give a talk at the Museum on Tuesday 13 October. Tickets can be booked here.

Smith's approach to mapping remains in use today. On 3 November, Oxford's Professor of Earth Sciences Mike Searle will give a lecture at the Museum on how he himself has used Smith's techniques to map the Himalaya, combining it with modern techniques.

The exhibition was supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

Tom Stoppard, Simon Schama, Stephen Greenblatt, the Assad Brothers and Christian Thielmann have been announced as Humanitas Visiting Professors at Oxford University over the next academic year.

This month, Professor Stephen Greenblatt will give two public lectures in Oxford as Humanitas Visiting Professor of Museums, Galleries and Libraries.

In Hilary Term next year Christian Thiemann will be Visiting Professor for Opera Studies and Tom Stoppard will be Visiting Professor for Drama Studies. In Trinity Term the Assad Brothers will share the Visiting Professorships for Classical Music and Simon Schama will lecture as Visiting Professor for Historiography.

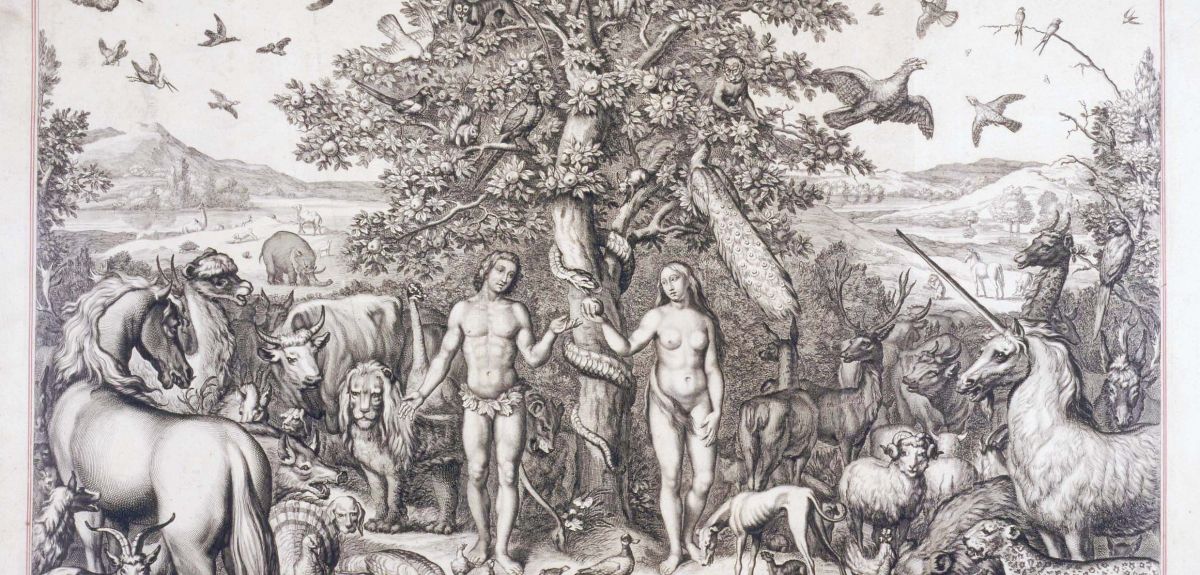

Professor Greenblatt will speak on the theme of 'The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve' in the Weston Library's Blackwell Hall on 19 October and the South School of the Examination Schools on 20 October.

He will also lead a graduate seminar in the lecture theatre of the Weston Library on 21 October.

Stephen Greenblatt is Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University. He is the author of twelve books, including The Swerve: How the World Became Modern and Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare.

His honours include the 2012 Pulitzer Prize and the 2011 National Book Award for The Swerve, the William Shakespeare Award for Classical Theatre, and two Guggenheim Fellowships.

Professor Greenblatt's visit has been organised by TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities, the English Faculty, and the Bodleian Library.

Humanitas is a series of Visiting Professorships at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge intended to bring leading practitioners and scholars to both universities to address major themes in the arts, social sciences and humanities.

Created by Lord Weidenfeld, the programme is managed and funded by the Weidenfeld-Hoffmann Trust with the support of a series of benefactors and administered by TORCH | The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities.

It can take botanists decades to accurately classify plants after they’ve collected and stored away samples from the wild. But now Oxford University researchers have developed a technique to streamline the process — and it’s already unearthing new species around the world.

In 2010, researchers from the Department of Plant Sciences, led by Dr Robert Scotland, published a paper that investigated how long it takes for plants to be described after they’ve been collected in the wild. The results came as a surprise: it turned out that just 14 percent of specimens were classified within five years, and on average it took 35 years for specimens to be recognised and classified as ‘new’. ‘People might imagine that researchers venture into the wild, point at something and say “that’s new”,’ explains Dr Scotland. ‘But it doesn’t work like that: mostly they get added to collections, then they're discovered at a later date.’

All the while, then, collected flowers sit dried and mounted on cardboard and placed in storage at herbaria for safekeeping. From their figures, the team estimated that of the 70,000 species of flowering plants thought to remain un-described, up to half may in fact sit in collections awaiting identification. Given the rate of discovery currently averages around 2,000 plant species per year, the team vowed to investigate whether there may be a way to expedite the process.

Generally, botanists perform one of two studies to describe plants in a given genus. The first, known as the Flora approach, is performed in a limited timeframe and describes all plant species in a particular country or region, using short descriptions and simple illustrations with no assessment of genetic differences taken into account. The second, referred to as the Monograph approach, takes a global view of all the species in a given genus, accurately demarcating each species and providing long descriptions, genetic analyses and detailed illustrations.

The latter is considered the gold standard in botanical taxonomy, not least because it provides a reliable means of identifying redundancies in existing classifications. But it often takes a long time to perform and involves intensive study. ‘It would be lovely to monograph the whole world, but that’s a pipe-dream,’ explains Dr Scotland. ‘Especially in the tropics, where there are too many plants, written about in too many places, often in too many different languages, with too much redundancy in existing names. The size of the task is just too big.’

Instead, the team thought there could be middle-ground between the two approaches. ‘We wondered if we might be able to combine some of the speed of a Flora approach with some of the rigour of a Monograph,’ explains Dr Scotland. ‘And we’ve ended up with what we call “foundation monographs”.’ The new approach combines the time-limited approach and short descriptions of the Flora approach with the genetic analyses and fieldwork of Monographs, enabling species to be uncovered quickly, but accurately. Crucially, it borrows content like drawings and genetic analyses, where they exist, from existing studies, in order to avoid duplicating work.

With a year of funding from Research Councils UK’s Syntax program, Dr Scotland’s team performed a one-year pilot study to create a foundation monograph for Convovulus (bindweed) — the first ever global study of the genus. It worked well: in 12 months, they recognised 190 species, including 4 new ones. ‘We showed that we’re able to catch the species that have slipped through the net in the past,’ explains Dr Scotland.

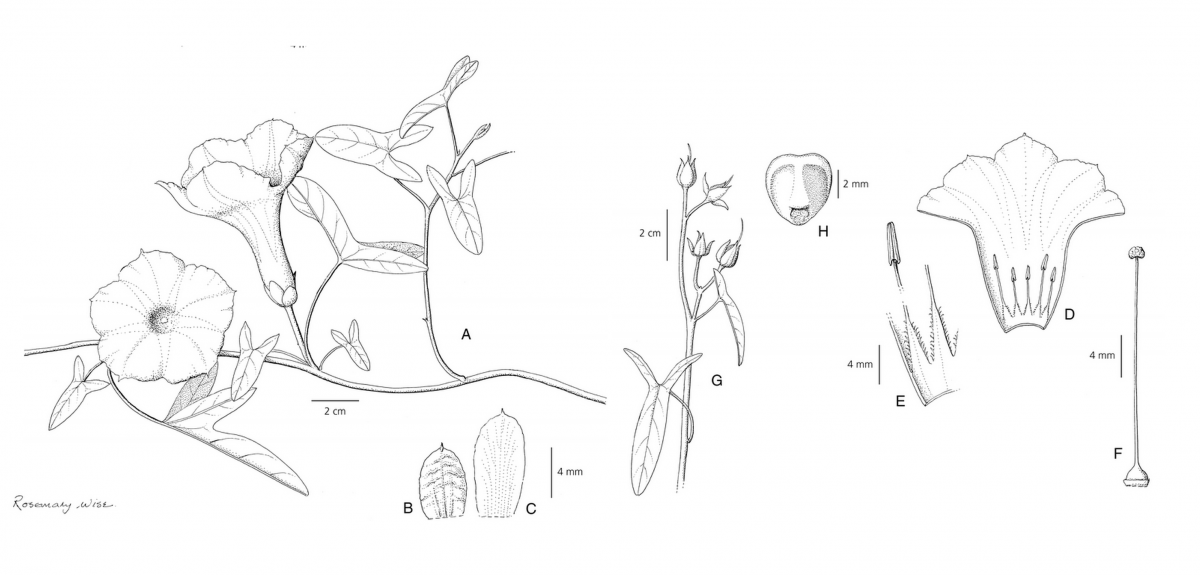

That was enough to help them secure a larger grant from the Leverhulme Trust to perform a three-year study of the Ipomoea (morning glories) genus — of which sweet potato is a member. Taking 1,500 samples from around the world, they sequenced DNA from the samples to identify key genes that can be used to create the genetic family tree of the species. Using those data, they were able to refute or corroborate existing species concepts, in the process identifying 18 new species and confirming the existence of 102 separate species in the genus from a single country, with many more to follow from other areas. From there, they were able to photograph and create detailed line drawings for those newly discovered species, finally publishing the foundation monographs in Kew Bulletin this September.

As far as Dr Scotland is concerned, we’re likely to see more species being identified like this in the future. “We’re probably seeing the end of the traditional approach to botanical taxonomy,” explains Dr Scotland.“That’s why we’re trying to do taxonomy in a time-efficient, clever way, at a scale that’s truly impressive.”

The most recent paper, entitled ‘Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in Bolivia’ is published in Kew Bulletin. The Convolvulus monograph, entitled ‘A foundation monograph of Convolvulus L. (Convolvulaceae)’, is published in Phytokeys. The illustrations for the research were funded by an NERC IAA award.

Despite huge efforts to treat and eradicate the disease, in 2013, 198 million people were infected with Malaria. 584,000 died. More than 525,000 of those deaths were African children aged under five.

Researchers are looking for new ways to target malaria, including vaccines and drugs, and important clues may lie in genes – our genes, the parasite’s genes and even those of the mosquito that transmits the parasites from person to person. A team based in Oxford and at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, just outside Cambridge, are working together with scientists and clinicians in more than 40 malaria-endemic countries to integrate epidemiology with genome science.

This is the Malaria Genomic Epidemiology Network (MalariaGEN), a global researcher community aiming to understand the genetic diversity in the human host, the malaria parasite and the mosquito vector. Last year the science blog spoke to the team about some of their initial findings, but their research has continued.

In the first of two interviews about research from MalariaGEN, we look at a study published in Nature, which found that genetic variation at a particular place in the human genome is responsible for protecting some children from developing severe malaria. The Oxford Science Blog put some questions to Dr Chris Spencer and Dr Kirk Rockett, two of the team behind the study. Their research reinforces earlier findings about a long-standing evolutionary battle between the human and malaria parasite genomes, each trying to outfox the other (the so-called Red Queen Hypothesis first coined by Leigh Van Valen in 1973).

OxSciBlog: In effect, some people are more resistant to malaria than others?

Answer: Yes. In regions where malaria is endemic, people are exposed to malaria (get bitten by mosquitoes carrying malaria) all the time. Most people will develop some form of illness with the classical symptoms (fever, sweating and chills) and sometimes this will develop into a severe, life-threatening disease. Young children are most at risk from severe illness as they have not yet had time for their immune systems to protect them, such that by adulthood they are less likely to become ill yet may be infected.

However, it is clear that some children are less likely to develop illness or severe disease than others. Some of these children have underlying conditions such as G6PD deficiency, thalassemia or sickle cell trait. All of these have been shown to have defined genetic polymorphism (mutations/changes). Studies such as ours allow estimates to be made of how protective these genetic changes are; individuals with sickle-cell trait for example are about 10 times less likely to develop any degree of illness from a malaria infection wherever they live compared with the general population.

This is a particularly strong effect and the other known protective genetic changes are providing generally between 20% and 50% protection. The other well-known example is the ABO blood group, where the genetic polymorphism which determines the O blood group also provides protection against malaria.

Questions remain as to whether there are other common genetic changes that protect from malaria and what happens in people with more than one polymorphism.

OSB: You carried out a genetic association study – what is that?

We've performed this test at over 10 million polymorphisms across the whole genome in thousands of individuals across Africa.

A: Don’t tell anyone, but a genetic association study is a very simple experiment! For the polymorphism you are interested in you measure which alleles of the polymorphism individuals carry.

For example, the sickle cell polymorphism has 2 alleles, either an A or a T, and we measure whether people have 2 copies of the A, 2 copies of the T or one copy of each. We then simply look to see if any of these alleles occur less often in children that develop severe disease than they do in the general population. If an allele is at a lower frequency in children with severe disease the implication is that this allele is protective.

The experimental and statistical complications come from the fact that we’ve performed this test at over 10 million polymorphisms across the whole genome in thousands of individuals across Africa and this generates a huge amount of data.

OSB: What did you find?

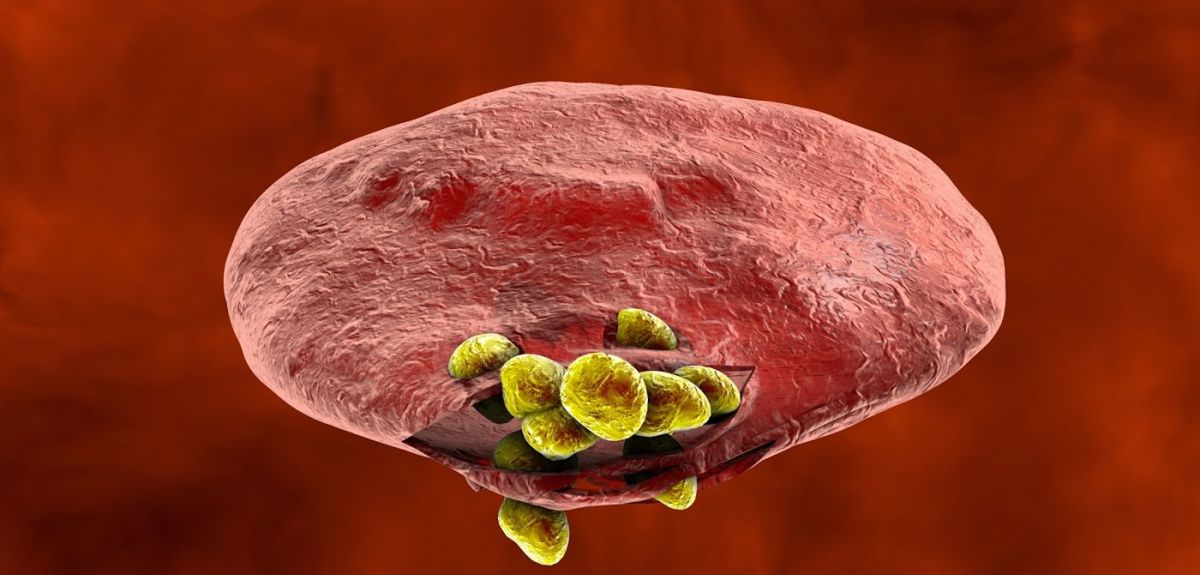

A: Our study identifies several new DNA variants that have a substantial protective effect for developing severe malaria. For one polymorphism in East Africa, the protective allele almost halved a child’s chances of developing life-threatening malaria. This DNA variant occurs near a set of genes belonging to the glycophorin family of genes, which express proteins on the surface of the red blood cells.

The discovery potentially links malaria susceptibility to one of only six clear examples of combinations of alleles (haplotypes) that have been maintained in human populations by natural selection. These alleles are thought to predate the time at which we split from chimpanzees some 5 million years ago. The genome is a big place and to find a haplotype of this kind slap-bang next to novel malaria susceptibility alleles is surprising, not least because ABO blood groups also show common polymorphism with chimpanzees. It is possible that susceptibility to malaria is part of the evolutionary mechanism sustaining alleles in the human population that would otherwise be lost by chance.

OSB: What are the implications for modern malaria research?

These genetics changes, whatever they do, have a major impact on the progression of infection either down the path to recovery, or to life-threatening disease.

A: Identifying the specific DNA variants that influence risk is the first step on a scientific path to understanding the mechanisms of disease. We can’t yet be sure what molecular biology underlies the variants that we observed, but there is good evidence that it relates to the nearby glycophorin genes which, when expressed as proteins on the red blood cell surface, are known receptors for the malaria parasite that help them bind and enter the red cell.

This reinforces the need to understand these host-parasite interactions, and our study means that we can pinpoint particular genetic changes which are unequivocally important in the outcome of infections – this allows scientists to focus future research with much more confidence and precision. On the flip side this research will also help to understand more about and parasite and how it has evolved and is evolving.

Our observation in this large population study proves that in real-world settings (as opposed to in a laboratory) these DNA changes provide strong protection against severe malaria. Rather than guessing as to what the relevant molecular biology is in malaria infections, our study says that these genetics changes, whatever they do, have a major impact on the progression of infection either down the path to recovery, or to life-threatening disease.

Countless animals have gone extinct over the years but the dodo is one of only a few to be remembered. A special day of events at Oxford University will investigate why this bird has remained so popular.

'The Oxford Dodo: Culture at the Crossroads' will be held on 18 November 2015 to celebrate the life and legacy of the dodo.

There will be a panel discussion of the dodo’s significance at 5.30pm in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, which is home to the world’s only preserved soft tissue dodo remains.

The panellists are from very different fields and will explore the dodo from a range of perspectives. They include Paul Smith (Director, Museum of Natural History), Pietro Corsi (historian of science), Jasper Fforde (children’s author), Paul Jepson (environmental researcher) & Kirsten Shepherd-Barr (literary scholar).

On the day, Oxford's Story Museum will host a children's workshop led by author Jasper Fforde, who will show how you can bring extinct animals to life through creative writing.

The University has also launched a writing competition, in collaboration with Blackwell’s, for 7 to 14 year olds, who will bring the dodo back to life through short stories and poetry.

The University has been awarded funding to hold the event as part of Being Human 2015, the UK's only national festival of the humanities. The event is organised by TORCH and the Museum of Natural History in Oxford and has been made possible by a grant from the festival organisers, the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Kirsten Shepherd-Barr, Oxford's Humanities Knowledge Exchange Champion and an English professor, said: 'The dodo: an icon of extinction, and a powerful symbol of humanity's impact on the environment. It crosses disciplinary lines, encompassing literature, science, the arts, geography.

'It haunts our imagination, from Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland to David Quammen's The Song of the Dodo to the Natural History Museum's very own exhibit on this extraordinary and elusive creative. What did it sound like? How did it really look? Why are we left to reconstruct, from a few bones, this creature that seems so real and touches us so immediately?'

Paul Smith, Director of the Museum of Natural History, said: 'Collaborating with Oxford Humanities researchers and sharing Dodo stories with the public is an excellent way to celebrate the power of museum objects and their ability to cross cultures, in this case the world’s only preserved soft tissue remains of the Dodo.'

Stephen Tuck, TORCH Director and Professor of Modern History, University of Oxford said: 'The dodo is such a symbolic character for so many fields, and this event is a great opportunity to bring those conversations together - and where better, than at the Museum of Natural History in Oxford?'

The event is free and open to the public, but booking is recommended. A ‘pop-up crèche’ for children up to 12 years old will be provided. Visit the TORCH website for more information.

- ‹ previous

- 143 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?