Features

For over 100 years engineers have known that hydrogen can cause metals to become incredibly brittle, but they've been able to do little to protect against it. Now, Oxford University researchers are working on a large collaborative project to build the metals of the future, that can retain their strength in the presence of this disruptive gas.

Steel has a reputation for being strong: it's used in everything from your car's chassis and the reinforced concrete joists that supports buildings, to the internal workings of jet engines and the cables that hold up the world's largest suspension bridges. But while advances in high-strength steel technology theoretically allow engineers to use less of the material – making it possible to create structures that are lighter as well as stronger – there exists a problem holding some of the materials back from widespread adoption.

'There are new materials sitting on the shelf that could be used for many kinds of applications – construction, aerospace, cars, all sorts,' explains Professor Alan Cocks from the University's Department of Engineering Science. 'But companies are afraid to use some of them because of their susceptibility to what's known as hydrogen embrittlement.' First observed before the turn of the 20th century, hydrogen embrittlement is a phenomenon where some materials – particularly steel, but also metals like zirconium and titanium – become far weaker when exposed to hydrogen.

Professor Cocks points out that some steels can suffer a decrease in strength by as much as a factor of 10 when they're exposed to hydrogen, which means that they could fail when subjected to just a tenth of the maximum stress they can usually withstand. If engineers could find a way to overcome this weakness, they could more confidently use some materials – predominantly steels, but also the likes of titanium for aerospace applications or the zirconium sheathing of nuclear power rods.

'It seems like it should be a straightforward problem to solve,' explains Professor Cocks. 'But there's immense controversy about why it happens, and despite lots of experimental studies and theoretical modelling there's still no real solution.' That's why researchers from Oxford University are working on a large collaborative project – along with Cambridge University, Imperial College London, King's College London and the University of Sheffield – to finally understand its causes and build new materials that overcome them.

To make progress, the researchers decided to put together a team that understood metals from the atom up. So the team includes Oxford scientists from the Department of Materials, who investigate how materials work at the atomic level, and from the Department of Engineering Science, who model the larger-scale properties of the materials and the ways that hydrogen can move through the metallic structure. Elsewhere around the UK there are teams that specialise in different aspects of modelling, as well as the design, fabrication and testing of new metals.

Just over a year into the project, the Oxford team are trying to understand exactly how hydrogen causes steel to become brittle. There are, broadly speaking, two competing schools of thought. The first suggests that the hydrogen atoms build up around tiny defects called dislocations in the metal's crystal structure, affecting the way the material irrevocably deforms. The second proposes that instead the hydrogen gathers at boundaries between chunks of metallic crystal known as grains, making it easier to pull them apart. 'We suspect it could be a combination of both,' admits Professor Cocks. 'But by modelling the process at different scales, we hope to find out once and for all.'

At the same time, the Oxford engineers are also proposing new ways to help steels cope in the presence of hydrogen. 'In the past, people have used coatings to protect against hydrogen being absorbed by metals,' points out Professor Cocks. 'But if you get a crack in that coating, you expose the material underneath. And anyway, because of its size, hydrogen can ultimately diffuse through any material, so a coating will only ever slow down the process.'

Instead, the team is seeking to develop a series of internal traps that can capture the hydrogen as it enters the metal. 'You can think of them as little sponges in the steel that mop up all the hydrogen so that it's not detrimental to the material properties,' explains Professor Cocks. So far the team has been studying how carbides – a type of carbon-metal compound – can be used within the microstructure of metals to such ends, because hydrogen appears to gravitate towards boundaries between them and grains of iron. The team hope that once they move to this boundary, the hydrogen will sit there benignly.

There are, of course, still plenty of questions that need to be answered before such techniques calm the minds of engineers keen to use these kinds of materials. Not least among them is what happens to the hydrogen stored within those traps: it may affect the material properties in an unexpected way. But that's why fellow collaborators in Sheffield and Cambridge are taking the work performed in Oxford, and by other partners, as a blueprint from which they can design and fabricate new types of steel to test in the lab.

Given the team has so far only spent just over a year's work trying to solve a problem that's persisted for over a century, you might not expect much progress so far. 'There are certainly a lot of challenges,' concedes Professor Cocks. 'But we think we're finally getting close to a point where everything will fall into the right place.' Much, one hopes, like the hydrogen itself.

HEmS is funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). It is a joint collaboration between the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Sheffield, and Imperial and King's Colleges London.

In Arts Blog we try to cover the latest research findings in the humanities and social sciences. But what about the story behind the research?

Here, Dr Alice Kelly, a Postdoctoral Writing Fellow in the Women in the Humanities Programme in TORCH | The Oxford Centre for the Humanities, explains how she made a recent discovery about Edith Wharton.

Dr Kelly found a typescript of a short story written by the Pulitzer Prize-winning American novelist, short-story writer and three-time Nobel Prize in Literature nominee. Titled 'The Field of Honour', the story is about the First World War.

"It was the title that originally caught my attention: an undated folder of writing marked ‘The Field of Honor’, catalogued between a number of drafts of short stories in the Edith Wharton Collection in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

Initially at Yale on a one-year Fox International Fellowship completing my doctoral dissertation on women’s First World War writing, I stayed on for a further two years, eventually teaching in the English Department and in the History Department of Wesleyan University, a nearby liberal arts college.

Working in the marble-clad Beinecke Library in the Wharton papers was the highlight of my time at Yale, and led to my discovery of this unknown First World War story and its significance in terms of Wharton’s war writings.

In an article published in this week’s issue of the Times Literary Supplement I provide a critical introduction and reproduce the story, which concerns Wharton’s anxieties about women in wartime and the relationship between America and France.

Not many people know that Wharton – the wealthy and globetrotting writer famous for her novels of high society, The House of Mirth (1905), Ethan Frome (1911), The Custom of the Country (1913) and The Age of Innocence (1920) – was also a war worker, reporter and author.

When the war broke out, Edith Wharton was living in Paris and very quickly became involved with relief efforts, establishing and managing four war charities, which would later gain her a number of military honours.

Although her writing slowed down during this period because of her extensive relief work, she still produced a considerable amount of war-related writing: a series of war reports published in American magazines and collected as Fighting France: From Dunkerque to Belfort in 1915; three short stories ‘Coming Home’ (1915), ‘Writing a War Story’ (1919), and ‘The Refugees’ (1919); the 1916 fundraising anthology The Book of the Homeless; and the novels Summer (1917), The Marne (1918) and A Son at the Front (1923), as well as a number of poems, newspaper articles and talks.

The story ‘The Field of Honour’ gives us a further demonstration of Wharton’s imaginative engagement with the war, particularly into the complexities of wartime politics and the role of women.

The story’s title, with ‘honour’ spelt in the English rather than American spelling (which was typical of Wharton) and meaning the battlefield or the field where a duel is fought, was originally a phrase referring to the medieval battleground, which became part of commonplace Great War rhetoric, and eventually represented post-war memorialisation efforts.

For First World War literary and cultural historians, it is impossible to read the phrase without thinking of its numerous wartime iterations. Reading the story for the first time – sitting in the library of the university which awarded Wharton an honorary degree in 1921 – I realized that the story was as rare as I’d originally thought, and gives us a greater insight into Wharton as a war writer.

After the neglect of Wharton’s war writing for a number of years, more recently there has been a critical reassessment taking place. My critical edition of Fighting France, Wharton’s collection of First World War reportage, will be published by Edinburgh University Press for its centenary in December 2015, along with restored original photographs and significant new archival material from Yale and Princeton.

My hope is that editions such as this one will contribute to new scholarship on Wharton’s war writing and the broadening canon of women’s First World War writing.

As a Women in the Humanities Postdoctoral Writing Fellow based at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), I am currently working on a broader study of modernist culture and war commemoration, examining the ways that writers, especially women writers, thought and wrote about death during and after the Great War.

I also run a twice-weekly Academic Writing Group for DPhil, postdocs and Early Career Researchers – which I’m sure Wharton, who wrote every morning in bed until noon, would have approved of."

In a guest post for Science Blog, Dr Tessa Baker from the Department of Physics writes about her work on alternative gravity. Dr Baker is one of the new generation of physicists trying to explain 'dark energy', and she recently received a 'Women of the Future' award.

In the late 1990s physicists discovered, to their consternation, that the expansion of the universe is not slowing but accelerating. Nothing in the 'standard model of cosmology' could account for this, and so a new term was invented to describe the unknown force driving the acceleration: dark energy.

We really have no idea what 'dark energy' is, but if it exists it has to account for about 70% of the energy in the whole universe. It's a very big ask to add that kind of extra component to the standard cosmological model. So the other explanation is that we are using the wrong equations – the wrong theories of gravity – to describe the expansion rate of the universe. Perhaps if it was described by different equations, you would not need to add in this huge amount of extra energy.

Alternative gravity is an answer to the dark energy problem. Einstein's theory of general relativity is our best description of gravity so far, and it's been very well tested on small scales; on the Earth and in the solar system we see absolutely no deviation from it. It's really when we move up to the very large distance scales involved in cosmology that we seem to need to modify things. This involves a change in length-scale of about 16 orders of magnitude (ten thousand trillion times bigger). It would be astounding if one theory did cover that whole range of scales, and that's why changing the theory of gravity is not an insane idea.

One of the real challenges in building theories of gravity is that you need to make sure that your theory makes sense at the very large cosmological scales, without predicting ludicrous things for the solar system, such as the moon spiralling into the earth. I don't think enough of that kind of synoptic analysis gets done. Cosmologists tend to focus on the cosmological properties and they don't always check: does my theory even allow stable stars and black holes to exist? Because if it doesn't, then you need to throw it out straight away.

Over the past decade hundreds of researchers have come up with all sorts of ways to change gravity. Part of the problem now is that there are so many different theories that if you were to test each one individually it would take forever. I've done a lot of work on trying to come up with unified descriptions of these theories. If you can map them all onto a single mathematical formalism, all you have to do is test that one thing and you know what it means for all the different theories.

In doing this mapping process we've discovered that a lot of the theories look very different to start with, but at the mathematical level they're moving along the same lines. It suggests to me that people are stuck in one way of thinking at the moment when they build these gravity theories, and that there's still room to do something completely different.

More recently I've moved on to developing ways to actually test the mathematics – to constrain it with data. For example, we can use gravitational lensing. If you have a massive object like a galaxy cluster, the light from objects behind it is bent by the gravity of the cluster. If you change your theory of gravity, you change the amount of bending that occurs. Basically we throw every piece of data we can get our hands on into constraining these frameworks and testing what works.

At this precise moment the data we have is not quite good enough to distinguish between all the different gravity models. So we are doing a lot of forecasting for the next generation of astrophysics experiments to say what kind of capability will be useful in terms of testing theories of gravity. There's still time in some of these new projects to change the design, and I hope to see some of these experiments come on line.

I am very grateful to my former supervisor Pedro Ferreira, who nominated me for the 'Women of the Future' award, and to the Women of the Future scheme. There are two sides to this award; one is the scientific work itself, and the other is the female leadership aspect. In the interview for the award we had quite an extensive discussion about the role of women in science, and what challenges they face. It's a global field-wide issue, and it is changing; it's just going to take time. And in fact Oxford Astrophysics is brilliant for women: Jocelyn Bell Burnell, Katherine Blundell, Joanna Dunkley – they're all really strong female role models.

This blog post first appeared on the Mathematical, Physical and Life Sciences Division website.

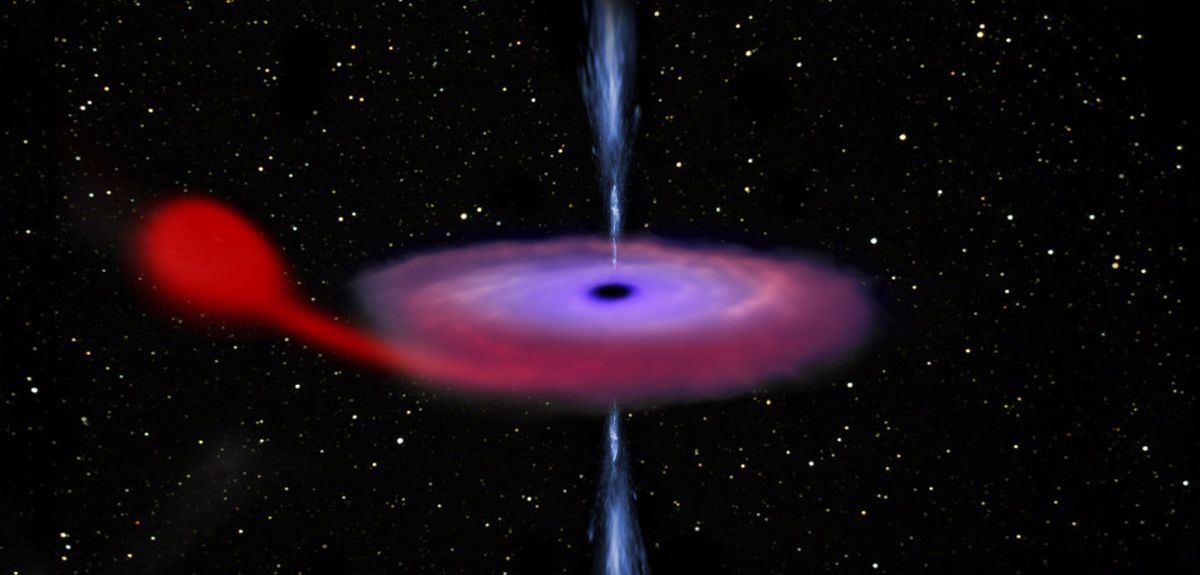

On 15 June 2015, V404 Cygni (V404 Cyg), a binary system comprising a sun-like star orbiting a black hole, woke up. A huge outburst of energy across the electromagnetic spectrum ‘lit up’ the sky. The last such outburst was 1989.

Dr Kunal Mooley, a Hintze Research Fellow at the University’s Centre for Astrophysical Surveys works on cutting-edge research based on the discovery and detailed study of transients at radio and optical wavelengths using a wide range of telescope facilities such as the Jansky Very Large Array, the Arcminute Microkelvin Imager (AMI), the Palomar Transient Factory, and the Giant Meterwave Radio Telescope. His research has revealed new physics operating in powerful galaxies called "active galactic nuclei" and has also uncovered intriguing extragalactic explosive events such as supernovae and gamma-ray bursts illuminating the dynamic radio sky. Recently, he carried out an intensive observing campaign with the AMI telescope at Cambridge to monitor V404 Cyg. This work, carried out in close collaboration with Professor Robert Fender of the Oxford Astrophysics sub-department, has helped paint a stunning picture how black holes can launch relativistic jets.

V404 Cyg was known to astronomers in the 18th century as a variable star in the constellation of Cygnus. Until the late 20th century, astronomers considered it to be a nova, a binary star system consisting of a white dwarf and a sun-like star undergoing sporadic outbursts. V404 Cyg first came into spotlight in 1989, when it underwent an outburst, releasing enormous energy over a span of a few months, and especially at X-ray, optical and radio wavelengths.

Not long after the outburst, it was recognised as a new class of X-ray transient sources, called low mass X-ray binaries (LMXBs). This class of transients contain a black hole devouring matter from its companion star, which is usually a sun-like main-sequence star. Through the 1989 outburst of V404 Cyg, astronomers learned a great deal about the accretion and jet-launching mechanisms in Galactic black holes. Once V404 Cyg returned to a quiescent state in the following year, astronomers were able to make accurate measurements of the motion of the companion star and calculate the masses of the two stars of the LMXB. The compact star was found to be twelve times more massive than the Sun, confirming that V404 Cyg contains a black hole. The companion star was about half as massive as the Sun.

During the 1990s, astronomers also reviewed archive data on V404 Cyg from optical telescopes, re-discovering two previous outbursts, in 1938 and 1956. So it appears that V404 Cyg undergoes outbursts every two to three decades. This likely results from material from the companion star piling up in a disc surrounding the black hole until a saturation point is reached. At this point the material is fed to the black hole rapidly, giving rise to an outburst.

Thanks to the Very Long Baseline Interferometric (VLBI) measurements of James Miller-Jones and coworkers, carried out in 2009, the distance of V404 Cyg from the earth is now precisely known to be 2.39 kiloparsecs (7800 light years or around 45.8 quadrillion miles).

On 15 June 2015 at 7:30PM BST, the Swift space telescope detected a burst of X-ray emission from V404 Cyg and sent out a worldwide alert via the Gamma-ray Coordination Network (GCN).

On 15 June 2015 at 7:30PM BST, the Swift space telescope detected a burst of X-ray emission from V404 Cyg and sent out a worldwide alert via the Gamma-ray Coordination Network (GCN).

The Arcminute Microkelvin Imager Large-Array (AMI-LA) telescope responded robotically to this trigger and obtained sensitive radio observations two hours after the trigger, once the source had risen in the sky.

This early radio observation, carried out at a frequency of 16 GHz, revealed a bright and already-declining radio flare. Early next morning we obtained another observation and found that V404 Cyg was still 200 times brighter than in quiescence. Following this initial detection, we launched an intense observing campaign with AMI-LA, and also triggered the eMERLIN array to get high resolution observations at 5 GHz. The radio observations carried out during the first few days of the outburst revealed several flares with increasing peak brightness and also characteristic oscillations in the intensity of radio emission on timescales as short as 1 hour. These oscillations are similar to those seen in previous LMXB outbursts, and are thought to be due to repeated ejection of matter from, and refilling of, the inner accretion disc.

The V404 Cyg outburst soon triggered a worldwide community of astronomers and amateur observers to perform coordinated observations across the electromagnetic spectrum, from the radio to gamma-ray wavelengths. During the outburst, V404 Cyg was exceptionally bright at optical wavelengths and, we could see it with a 14-inch telescope from the centre of Oxford! So I teamed up with Fraser Clarke, a Systems Engineer in the Astrophysics sub-department, to observe the source with the 14-inch Philip Wetton telescope on the roof of the Denys Wilkinson Building. We obtained measurements simultaneous with the AMI-LA observations to understand the correlation of flares at these two distinct wavelengths. Some flares appeared to be correlated, giving clues about the optical emission mechanism of the outburst. On some occasions, the emission at optical wavelengths arises from the base of a jet launched by the black hole, which expels the accreted matter in the form of a collimated outflow – an outflow in a specific direction. At these times, the radio emission arises from further down the jet, and the time lags between the flares seen at these two different wavelengths gives us the distance of the radio emitting region from the black hole, estimated to be a few thousand light seconds.

V404 Cyg was exceptionally bright at optical wavelengths and, we could see it with a 14-inch telescope from the centre of Oxford!

With the AMI-LA and the eMERLIN telescopes, we have the earliest and widest coverage of V404 Cyg's 2015 outburst at radio wavelengths, which lasted for 30 days. A large number of radio flares were seen, likely associated with relativistic ejections of the accreted matter.

VLBI observations during the outburst carried out by James Miller-Jones, a professor at the Curtin University in Perth, have indeed revealed blobs of plasma ejected by V404 Cyg and moving at speeds close to that of light. We would expect the direction of motion of the blobs to be aligned with the spin axis of the black hole, but we also have hints of blobs moving at two different angles from the VLBI observations. This could be attributed to the precession of the black hole spin, just like a spinning top precesses when set into motion. On 27th June, the biggest radio flare was seen in V404 Cyg, making it one of the brightest sources in the 16 GHz sky for a few hours. After this flare, V404 Cyg started its descent into quiescence.

With the outburst over, our research group at Oxford has turned its focus from radio observations and data processing, to compiling multiwavelength data, analysing and interpreting all the data together, and modelling the flares in order to extract the interesting physics of the V404 Cyg's outburst.

Erik Kuulkers, the project scientist for the INTEGRAL Gamma Ray observatory at the European Space Agency, aptly refers to the 2015 outburst of V404 Cyg as 'a once in a professional lifetime opportunity'. With the outburst over, our research group at Oxford has turned its focus from radio observations and data processing, to compiling multiwavelength data, analysing and interpreting all the data together, and modelling the flares in order to extract the interesting physics of the V404 Cyg's outburst. With the unique data set at hand, we aim at deriving the kinetic calorimetry - the energetics of the outburst, and, for the first time, directly compare the jets launched by black holes residing in own Galaxy with those launched by supermassive black holes residing at the hearts of powerful galaxies called active galactic nuclei (AGN).

About the Arcminute Microkelvin Imager Large-Array (AMI-LA) and the ALARRM observing mode

The AMI-LA is an array of eight 12-metre telescopes located at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory (MRAO) in Cambridge. It observes between frequencies of 14 and 18 GHz. Since 2013, the AMI-LA Rapid Response Mode (ALARRM) has been running where the array is robotically overriden on the basis of Swift triggers. For a suitably positioned source in the sky the array can start observing the target within minutes, delivering a 2 hour observation centred at 16 GHz. This programme has been extremely successful and, to date, more than 150 events have been followed up robotically, delivering exciting science. The ALARRM mode initially began as part of the 4 Pi Sky project whose Principal Investigator is Robert Fender from the Astrophysics sub-department at the University of Oxford.

We probably all know someone who has dementia. By 2025, there will be 1 million people affected by it in the UK. Alzheimer’s disease is well known as the most common cause of dementia. But what about the third most common cause of dementia, Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB)?

Dementia with Lewy bodies

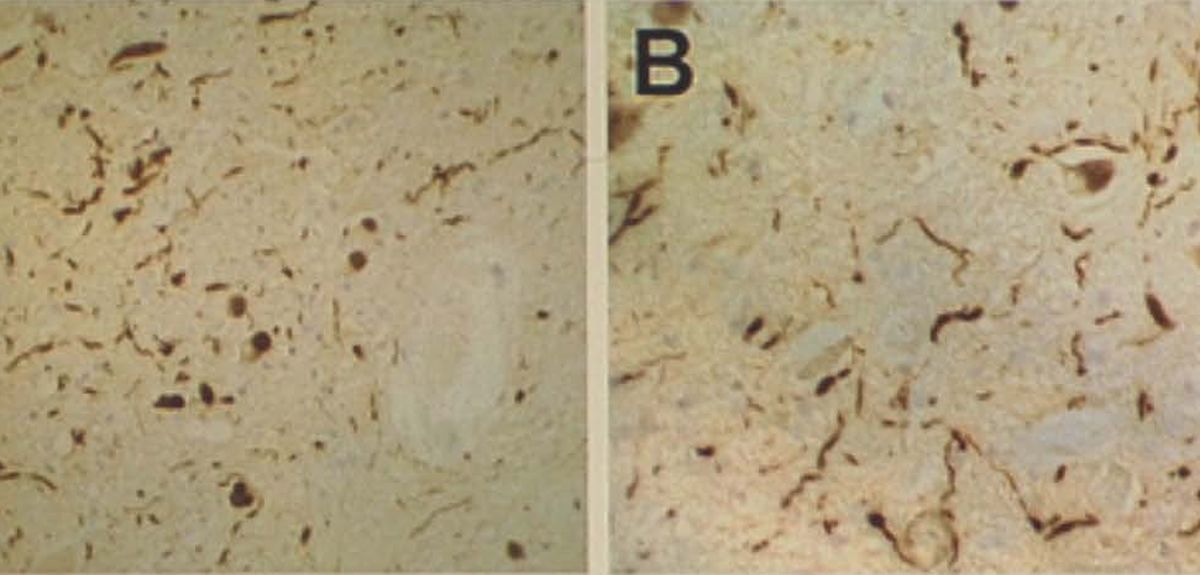

Frederic Henry Lewy, a prominent Jewish German-born American neurologist, first described the phenomenon that came to be known as 'Lewy bodies' in 1912. These 'bodies' are clumps of a sticky protein called alpha-synuclein that build up in nerve cells in the brain, causing damage and eventually death to these cells. Typically, they affect the cells that control thinking, memory and movement. In fact, Lewy bodies are the underlying cause of several progressive diseases affecting the brain and nervous system, including not only DLB but also Parkinson's disease.

We tend to get rid of this particular alpha-synuclein protein quite slowly, using a sophisticated 'clean-up crew' of enzymes. Studies of the brains of people who have died as a result of DLB have shown that one of these sets of enzymes is abnormally increased in the cells that contain the toxic protein clumps.

On the face of it, this may not seem to be a problem, but the system of waste-disposal enzymes is a complex one. They each have different roles and work together to regulate the level of alpha-synuclein. One set of enzymes is responsible for directly attacking the protein, whereas another – the one that is abnormally increased in DLB cases – counteracts this action. This set of enzymes works to either elongate or trim off a tag on alpha-synuclein. This tag is made up of molecules of a small protein called ubiquitin, and its regulation goes awry in patients with DLB.

Targeting the abnormally increased enzyme

Associate Professor George Tofaris, together with his research group in the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, is working on the development of targeted biological therapies in neurodegenerative disorders. George explains that when it works, this tagging system is essentially 'a kiss of death for proteins, but a kiss of life for the cell because it gets rid of unwanted or toxic proteins'.

Alzheimer's Research UK has allocated £50,000 to George and his team to investigate how the enzymes in the ubiquitin system might be targeted, in order to improve the disposal of alpha-synuclein. So how will the team go about this ambitious project over the next two years?

The first step is to work with others on screening the hundreds of possible chemical compounds that may have an effect on such enzymes in the test tube. Researchers will identify the structures of the compounds and make computational improvements in order to refine the list of compounds that will be used in the next stage of the experiment.

Moving on the second stage, George and his team will test the compounds on human brain cells. Researchers can create cortical neurons and dopamine cells – the brain cells affected by Lewy bodies – from skin cells, by using genes that regulate gene expression. This stem-cell technique is invaluable in allowing scientists to go straight from the test tube to working directly on a real human brain cell. The team will treat these brain cells with compounds and see which one has the most success in destroying the clumps of alpha-synuclein that can be triggered in these cells.

Neurological research such as this is mirroring the work that has been going on in the field of cancer for some time: targeting specific enzymes that have been identified in the lab as having a critical role in disease.

Paving the way for a new drug

After identifying an effective compound, the next step would be to test it in animals to see how the drug might affect the whole system, and to find out whether it can get through the blood brain barrier, a semi-permeable membrane separating the blood from the cerebrospinal fluid.

The good news is that even if this work doesn’t eventually result in a drug in tablet form, scientists will at least be in possession of good tools that can be used to manipulate alpha-synuclein and better understand how it is targeted for destruction.

- ‹ previous

- 140 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?