Features

It sounds like the perfect arrangement. The plant receives vital nutrients such as phosphorous and potassium, and in return the friendly fungus gets the sugars and carbon it needs.

But there might be something more sinister going on, according to evolutionary biologists at the University of Oxford.

In such partnerships – known as mutualisms – two species work in close cooperation with one another. In the case above, a mycorrhizal fungus will latch on to a plant's roots, setting in motion a mutually beneficial trading of resources.

In a new paper published in Nature Communications, however, researchers have shown using mathematical modelling how one species can end up becoming the dominant partner in the relationship, doing harm to the other and forcing it to become more dependent.

Professor Stu West of Oxford's Department of Zoology said: 'What we're looking at in this paper is the theory that when you have two species cooperating, one can be "favoured" – or naturally selected – to harm the other. This makes things tougher for the other species, causing it to become more reliant.

'The specific example we're looking at is the interaction between plants and mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi connect to the roots of plants and in effect "trade" resources. The plants give sugars and carbon to the fungi, and in return the fungi provide nutrients like phosphorous and potassium.

'If the fungi can make it harder for the plants to acquire these resources – and there is empirical evidence that fungi can upset the physiology of plants and their ability to get these resources directly, which sparked our theory – then the plants are forced to trade with the fungi.'

According to Professor West, a good analogy is that of an economy: if you can monopolise a resource, you'll get better trade for it.

He said: 'We've always known that species interact like this with one another, but here we’re seeing the darker side of that. Even when individuals are cooperating, they're still looking out for their own interests. One is essentially double-crossing the other.'

To demonstrate this, the researchers set up a series of resource-trading 'games' in which one of the partners – in this case, the fungi – had the opportunity to evolve an ability to harm the other. As it turned out, they evolved this ability quite easily.

Professor West added: 'This could, in theory, apply to any sort of interaction between species. It's something we should be looking out for.'

Renowned cellist Natalie Clein has joined the University as Director of Musical Performance in the Music Faculty.

Ms Klein, who has been appointed for a four year term, regularly performs in Oxford’s major music venues, most recently performing the complete Bach cello suits in the Sheldonian Theatre.

As Director of Musical performance, she will take a leading role in concert programming, developing new artistic projects, and introducing new modes of teaching.

This will begin with a Bach project in autumn 2016 and visits from a number of leading contemporary composers.

The Faculty of Music at Oxford University is delighted to announce the appointment of cellist Natalie Clein as its Director of Musical Performance for the next four years.

The wider community in Oxford will also benefit from Ms Clein’s new position. On 1 June this year she will give a recital of Debussy, Kodály, Kurtág, Britten and Prokofiev with pianist Christian Ihle Hadland.

'Ever since I first visited Oxford as a student and then later as a professional cellist performing at the Sheldonian, Holywell and Jacqueline du Pré, it has occupied a place of great significance in my consciousness, both intellectually and artistically,' she said.

'So it is with great excitement that I take on this newly created position. My ambition over the next four years is to bring students, international artists and academics from across the cultural spectrum together in dialogue and a spirit of discovery.'

Michael Burden, Chairman of the Music Faculty, said: 'Natalie brings with her a wealth of experience and has already inspired an unprecedented response among the students.

'The integrity of her playing speaks for itself. Her time at the University has already been artistically productive for everyone who has the opportunity to work with her.'

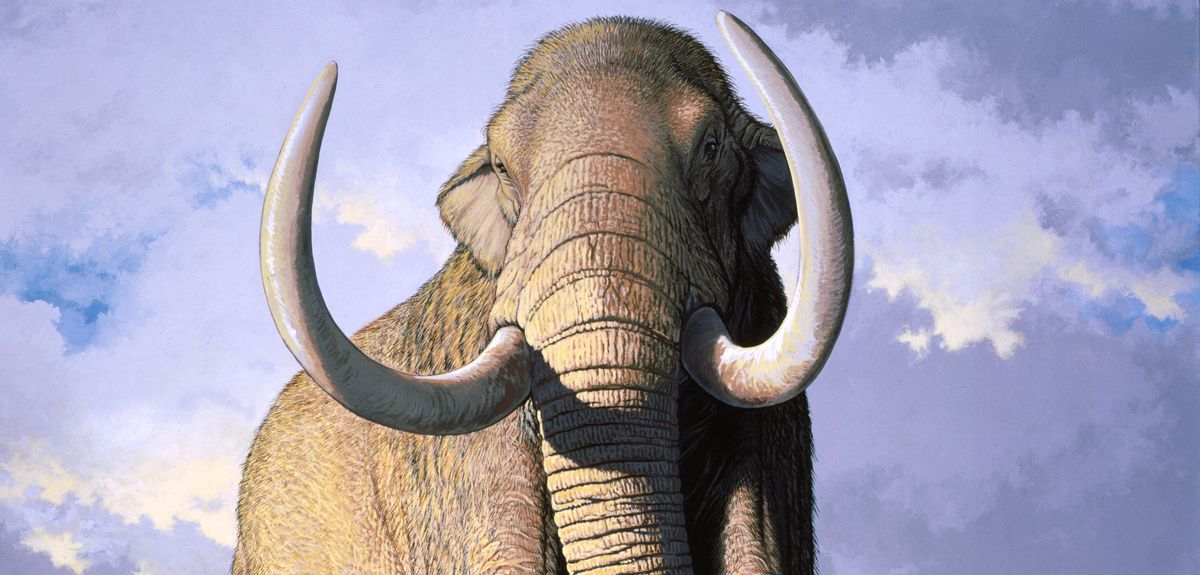

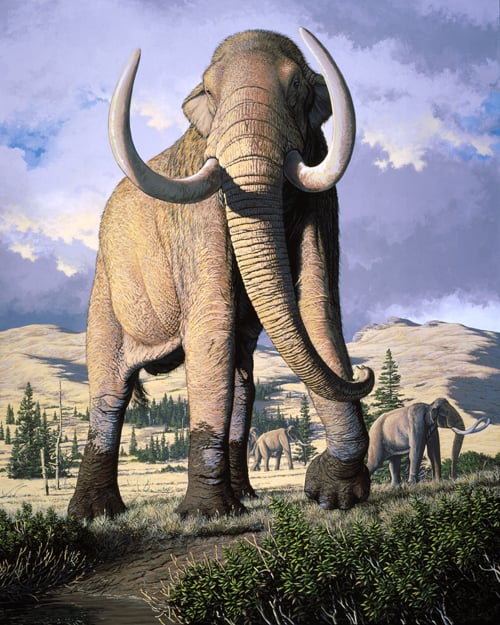

Following a successful conference on megafauna - large animals - two journals have published special features on the topic. Professor Yadvinder Malhi from the Environmental Change Institute, part of the School of Geography and the Environment explains:

This week sees the publication of two special features, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Ecography with 24 papers examining how megafauna affect ecosystem and Earth System function. This topic is based on a conference we held on Oxford in March 2014, and features on the cover of both journals.

In almost all land regions the decline and disappearance of these large animals, the megafauna, has been associated with the sudden arrival of modern humans, with only Africa and southern Asia, with a longer human prehistory, having pockets of substantial remaining megafauna.

We live in the shadows of lost giants. Until relatively recently almost every major vegetated land area on Earth possessed an abundance of large animals that we now only associate with African game parks. Mesmerizing early art shows how much these giant creatures dominated the psyche of our ancestors. They included larger relatives of familiar creatures such as elephants and lions, but also exotic wonders such as giant sloths, car-sized glyptodonts in the Americas, rhino-sized marsupials in Australia, and gorilla-sized lemurs in Madagascar. The oceans also hosted a high abundance of giants, which linger on in greatly reduced populations after the advent of commercial whaling.

Over the last 50,000 years, a blink of an eye in geological and evolutionary time, something extraordinary happened. These giants have disappeared completely from many continents, and been greatly reduced in diversity, abundance and range in other continents. In almost all land regions the decline and disappearance of these large animals, the megafauna, has been associated with the sudden arrival of modern humans, with only Africa and southern Asia, with a longer human prehistory, having pockets of substantial remaining megafauna. The evidence of strong decline is earliest in Europe and Asia, but most dramatic in Australia, the Americas and islands such as Madagascar and New Zealand. Much has been written about the size and cause of this decline, but much less on its consequences on the broader environment.

Too little of our thinking about contemporary ecosystems, whether marine or terrestrial, reflects that these are ecosystems missing a major functional component with which they co-evolved. It is likely that there are many “ghosts” of the megafauna in the structure and function of the contemporary biosphere. When we wander out into the closed woodlands of, say, Europe or North America, the woody savannas of South America or the fire-dominated drylands of Australia, it is worth reflecting on the elephants or other giants that were there just recently, and how even the most apparently pristine ecosystems may still resound with the echoes of their absence.

In March 2014, we convened a major international workshop at St John's College Oxford, supported by the Oxford Martin School, and gathered a large number of international experts from disciplines ranging from paleoecology and anthropology through to conservation science and policy . The workshop was the first international meeting focused on the impacts of megafauna and megafaunal loss. It started by looking at the causes and impacts of past megafaunal loss, and then moved on to looking at contemporary studies around the world, ranging from work in savannas of Africa to 'megafaunal rewilding' experiments in Europe and Russia. Finally it examined the challenge on ongoing loss of megafauna, and explored the potential and consequences for bringing back megafauna in selected landscapes, and what it means for conservation thinking and science. The proceeding of the conference have led to two special features in scientific journals, which were published on January 26th 2016. Ten papers are published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and 14 in Ecography.

Collectively, the studies show emphatically the large impact that megafauna have on various aspects of the environment, ranging from vegetation structure and composition, species composition, through fire patterns, soil fertility and nutrient flow in both land and oceans, and even regional and global climate by affecting land surface reflectivity and atmospheric methane concentrations. The loss of megafauna cascades through all levels of functioning of ecosystems. Even the apparently wildest contemporary landscapes likely carry the legacies of lost megafauna, and the consequences of contemporary decline of elephants and other megafauna may be felt for centuries or millennia to come. This improved understanding of the many ways that megafauna have influenced ecology and biogeochemistry may also help identify hitherto underappreciated and unidentified 'ecosystem services' that our planet's remaining giants provide – or could provide if megafaunas were allowed to recover.

Taking the latter perspective, the special features conclude by looking forwards, and exploring the potential of a 'megafaunal rewilding' agenda to shape how with think about nature conservation, and how we maximize landscape vitality and resilience in the changing and pressured environments of the Anthropocene. Much of the world is still suffering ongoing loss of its remaining wild large animals, often even within protected areas, as illustrated by dramatic and urgent rhino and elephant poaching crisis in Africa. However, in some regions a new dynamic is taking place, where megafaunas are undergoing unprecedented recoveries. These involve spontaneous recolonizations in response to societal changes, e.g., the return of wolves to Western Europe in recent years. It, however, also includes an increasing number of megafauna reintroductions, not just to aimed at restoring these magnificent species, but also their ecological effects. We need to understand how best to implement rewilding in the human-made landscapes that increasingly cover the Earth and its functionality in such settings. It is important think practically about how to develop strategies for implementing rewilding in ways that will allow it to realize its potential transformative role for nature conservation in the 21st century. The ghosts of the past megafauna may still have lessons for how to maintain life on a human-dominated planet.

'Humanities and the Digital Age' is the topic of this year’s Annual Headline Series in The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

Over the next year, academics and practitioners from many different disciplines will discuss the relationship between the humanities, machines and technology.

The first event takes place tomorrow evening with a debate about what it means to be human in the digital age.

It will bring together a panel of experts from across the Humanities and the cultural sector to examine how the digital age has shaped, and will continue to shape, the human experience and the humanities.

The speakers will be Diane Lees CBE (Director-General of Imperial War Museum Group), Professor Emma Smith (Fellow and Tutor in English, University of Oxford), Dr Chris Fletcher (Professorial Fellow at Exeter College, Member of the English Faculty and Keeper of Special Collections at the Bodleian Library), and Tom Chatfield (author and broadcaster). The discussion will be chaired by Dame Lynne Brindley (Master, Pembroke College and Former Chief Executive, British Library).

It will be held at 5.30pm in the Mathematical Institute on the University’s Radcliffe Observatory Quarter. For those who cannot attend in person, the event will be live-streamed.

Dr Chris Fletcher, Keeper of Special Collections at the Bodleian Libraries, will discuss the continued and even increasing interest in the analogue form of the word – whether printed book or archival manuscript – as well as the vibrant cultures of the digital in libraries and the challenges of digital preservation.

Are we in danger of losing the history of the future, and how do we preserve and make it available to present and future generations of scholars?

Dr Emma Smith of the Faculty of English Language and Literature will ask whether in this modern age we will lose our 'ability to forget'.

'My talk considers this as a particular problem of the internet age, and, contrary to claims that we should be preserving and archiving more and more data, makes a case for the creative possibilities of digital obsolescence,' she says.

'I discuss the ways digital recording and archiving of theatre productions threatens something intrinsic to theatre itself, and think about the ways that the right to be forgotten, currently articulated around discharged criminal convictions or youthful indiscretions, might be something to embrace more fully as we think about the art of the digital age.'

Diane Lees, Director-General of the Imperial War Museum in London, will explain how digital tools have helped the Museum’s research and public engagement, focusing on crowd-sourcing projects like Lives of the First World War and The American Air Museum website.

Tom Chatfield, an author and commentator on digital culture, will explore our relationships with machines and technology. 'If we wish to understand our own natures, machines aren’t going to solve our problems or even point us in the right direction,' he says.

'And if we wish to build not only better machines, but better relationships with and through machines, we need to start talking far more richly about the qualities of these relationships; how precisely our thoughts and feelings and biases operate; and what it means to aim beyond efficiency at lives worth living.'

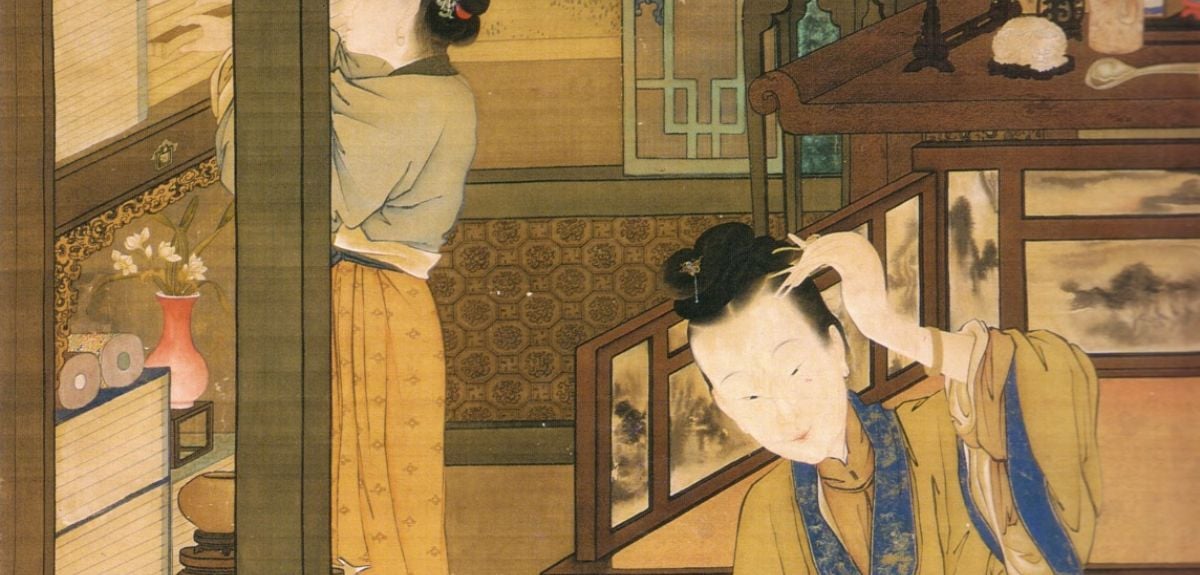

Free public lectures on the history of Chinese art begin tomorrow.

The Slade Lectures will this year be given by Wu Hung, a specialist in East Asian art at the University of Chicago.

He is the Harrie A. Vanderstappen Distinguished Service Professor of Art History and East Asian Languages and Civilizations and Director of the Centre for the Art of East Asia in Chicago.

Professor Hung's lecture series is titled 'Feminine Space: An Untold Story of Chinese Pictorial Art'.

There will be a lecture every Wednesday at 5pm in the Mathematical Institute on the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter, beginning at 5pm. There will also be an informal lecture on Professor Hung’s own experience of curating contemporary Chinese art on Monday 29th February.

Craig Clunas, Professor of the History of Art at the University of Oxford, says: 'It is a great pleasure to welcome Professor Wu Hung of the University of Chicago, one of the world's leading scholars of Chinese art, to deliver this year's public Slade Lecture series in Oxford.

'Wu Hung has written extensively on Chinese art from ancient times to the contemporary art scene, always bringing fresh and exciting ideas to the subject in a way which is accessible to non-specialists.

'His free lectures on the development of Chinese painting from the point of view of 'feminine space' will be of interest to anyone concerned with the visual arts.'

The full timetable of this year's Slade Lectures is available here.

- ‹ previous

- 134 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?