Features

The Ruskin School of Art is holding a sale of student artwork this weekend.

The Ruskin Art Sale will take place from 10am to 4pm on Saturday and Sunday (13/14 February) at 74 High Street.

The walls will be full of artworks from undergraduate and Master’s students at the Ruskin School of Art.

Visitors can browse or buy the art and enjoy some live entertainment and Valentines-themed refreshments.

'The Ruskin Art Sale is a great opportunity for the larger Oxford community to buy high-quality artworks by made by artists at the start of their careers,' says Professor Hanneke Grootenboer, head of the School.

'The proceeds go towards the organisation of the annual Ruskin Degree Show that takes place on June 17. Come and join us: is a great chance to meet art students and stroll around our beautiful building.'

A scratch from a rose thorn while gardening. It’s an easy injury to pick up even if you’re being careful. It’s annoying but no more than that. If that scratch were to be in your mouth, that would be unusual, unfortunate and maybe a little embarrassing.

But what if it gets infected? That’s inconvenient – you’ll have to go to your GP, who can prescribe an antibiotic that will soon clear things up. It’s hardly life threatening.

Today, with a range of antibiotics available, we take for granted our ability to cure infections. Yet, it’s only 75 years since a team of Oxford University researchers proved that penicillin could fight infections in people.

In December 1940, the story goes that Albert Alexander managed to scratch his mouth while pruning roses. The scratch became infected and in 1941 he was in Oxford’s Radcliffe Infirmary with abscesses around his face.

In fact, there is no evidence for the rose thorn story. Instead, there is evidence that Albert, a police officer in Berkshire, had been sent to Southampton under wartime mutual aid arrangements between police forces. While there, he was injured when a bomb struck a police station.

However the injury was caused, what is undisputed is that he was admitted to the Radcliffe Infirmary with a painful and incurable infection. However, he was about to make a major contribution to the development of drugs that have saved millions of people.

From mould to medication

Two years previously, as Europe descended into war, a team in Oxford led by Dunn School head Howard Florey had begun work on penicillin. Since 1928, Alexander Fleming, who had discovered penicillin’s antibiotic effects, had tried to interest scientists in researching how to purify, and thus derive products from, the mould.

Florey and Ernst Chain turned to penicillin as part of a comprehensive programme of research on antibacterial substances, began work on penicillin at Oxford. Chain soon extracted material that had antibacterial activity from penicillin cultures. Tests on mice showed that this antibacterial substance was not toxic.

Norman Heatley, whose plan to work in Denmark had been stymied by the outbreak of war, was brought into the team. He first devised the cylinder-plate diffusion technique that provided a reliable and sensitive assay for penicillin and that was later adopted as the standard assay for antibiotic activity. He then suggested a procedure for purifying penicillin extracting from organic solvents, in which penicillin was soluble, a stable salt that was soluble in water.

In the face of wartime shortages, the team turned their lab into a penicillin factory, first using bedpans and then specially-made pottery vessels designed by Heatley. Further experiments on animals confirmed penicillin’s potential.

More about the Dunn School of Pathology’s work on penicillin

BBC One Show feature on Norman Heatley’s contribution to penicillin research (Starts at 21:45)

Penicillin into people

After many months of preparative work, the team accumulated enough stable penicillin to permit trials on people with normally fatal bacterial infections. On 12 February 1941, their first patient was Albert Alexander. He received an intravenous infusion of 200 units of penicillin.

The results were initially excellent. Within 24 hours, Albert Alexander's temperature had dropped and the infection had begun to heal. But then the penicillin ran short. The team extracted penicillin from their patient’s urine to reuse it but after five days there was no more. Sadly, Albert Alexander relapsed and died on 15 March.

Penicillin into production

Further trials were more successful, but the key issue was generating a large enough quantity of penicillin. Florey and Heatley travelled to America, where they persuaded both US government and industry to industrialise penicillin production. The target was to have penicillin available in sufficient quantities for the medical support to the planned invasion of Europe. By D-Day (6 June 1944), the allied armies were well stocked with penicillin to treat war wounds. On 15 March 1945, Penicillin could be made available over the counter in US pharmacies, although it would not be available to British civilians – as a prescription drug – until 1 June 1946, the year after Florey and Chain received a Nobel prize for their work.

More about the industrialisation of penicillin production

Today, we live in an antibiotic era, able to deal with minor infections long before they become serious, never mind fatal. Oxford University researchers continue to develop our understanding of disease and its treatments, looking for new cures, improving established ones. Local people continue to volunteer for trials. Over the years, we have worked to beat many diseases; over the coming years, we plan to beat many more.

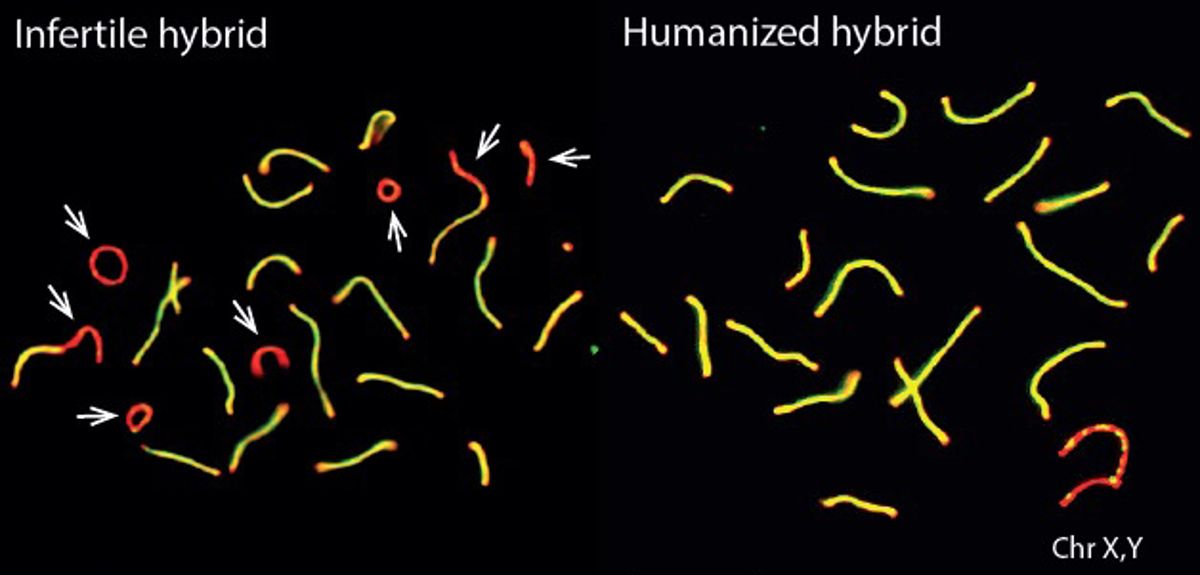

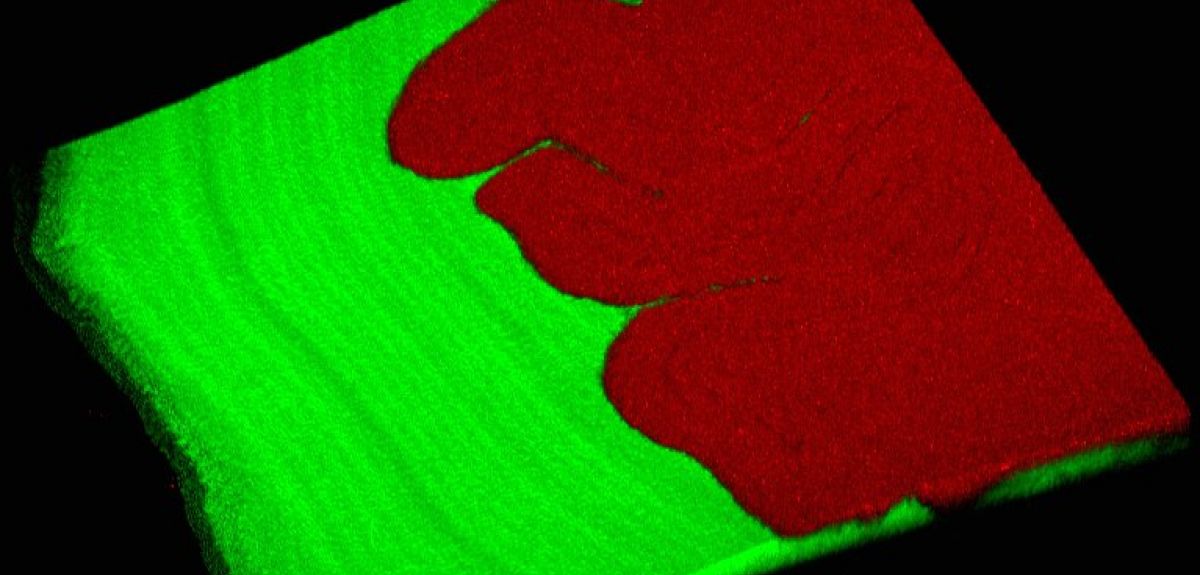

A study by researchers at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics at Oxford University has uncovered the key role played by a single gene in how groups of animals diverge to form new species. The study, published today in the journal Nature, restored fertility to the normally-infertile offspring of two subspecies of mice, by replacing part of the Prdm9 gene with the equivalent human version. Despite the nearly 150 million years of evolution separating mice and humans, these 'humanized' mice were completely fertile.

New animal species form when groups of animals become isolated and as a result, begin to separate through evolution (a process known as speciation). When these isolated populations meet later, they might be able to breed with each other, but the male offspring are often infertile. Horses and donkeys are an example of such speciation: they can interbreed, but their offspring, mules, are infertile.

'Our work studied similar infertility in hybrid house mice, whose two parents come from different subspecies found in Western and Eastern Europe', says Dr Ben Davies from the Nuffield Department of Medicine, the first author on the study. These two sub-species are therefore on the verge of splitting into two entirely different species, since like mules, their offspring are infertile.

Dr Davies and his colleagues studied the Prdm9 gene: this gene is already known to have a role in infertility in mice from different species, and is in fact the only known speciation gene in mammals. However, how speciation might link up to infertility was unknown.

A previous clue came from earlier work by Professor Simon Myers and Professor Peter Donnelly, the two senior authors on this study. Their work had found that the protein produced by the Prdm9 gene determines where in the genome maternal and paternal chromosomes exchange genetic information: a process known as recombination, which controls how genes are passed down through a species.

To figure out the exact involvement of the gene in how species form, the transgenic, chromosome dynamics and the genomics core facilities at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics came together to carry out a new study. The groups replaced the region of the mouse Prdm9 gene responsible for DNA binding with the equivalent sequence from humans, thus completely changing where recombination happened along the genome.

'The effect of this change was startling', says Professor Myers. 'When these humanized mice were crossed with mice from the other subspecies, the offspring were no longer infertile but were instead fully fertile: inserting a key part of the human version of the gene into the mouse DNA binding domain had completely reversed the infertility of hybrid mice.' Speciation thus seems to be a potentially reversible event, at least in mice, where the human allele mimics what may happen when a random Prdm9 mutation occurs.

Only the binding properties of PRDM9 protein were changed in the experiment, so the researchers also investigated PRDM9 binding to DNA in more detail. They found that the infertile mouse hybrids showed a striking pattern: the mouse PRDM9 protein would bind to one of their chromosomes or the other, but not both. This happened even though the two copies of each chromosome they carry – one from each subspecies – are more than 98% similar overall.

The researchers discovered that this strange binding pattern came about because over many generations, the normal mouse PRDM9 protein erodes the DNA sequence it binds to, resulting in the asymmetric chromosome binding pattern seen in the infertile hybrids. The researchers think that asymmetric binding makes it more difficult for chromosomes to successfully identify and make contact with each other as egg and sperm cells are formed. The result is that in many different hybrid mice, asymmetric PRDM9 binding is associated with an increasing failure rate in chromosomes making contact correctly, leading to more and more fertility problems.

'We think that the symmetric marking of chromosomes by PRDM9 facilitates their pairing: where PRDM9 binding is very asymmetric, this leads to difficulties in pairing, failure in recombination repair and, at one extreme, the infertility we see in some mouse hybrids', says Professor Donnelly. 'These results also highlight just how important it is to understand the co-evolution of the Prdm9 gene with the whole genome in which it resides: we now have a new mechanism for reproductive isolation of closely related subspecies.'

The research team are now busy re-engineering different version of the Prdm9 gene to explore further, and they hope to find out how exactly the symmetry of DNA binding can influence the pairing of chromosomes.

Fearless in the face of corporate interests and revealing information from even the most secretive laboratories, Policy 0043 is unique, making the European Medicines Agency (EMA) the most open and transparent medical regulator in the world. Since its adoption in 2010, the policy means the EMA is the only regulator in the world to freely and unconditionally release clinical trial data from its holdings.

Open data is vital... Evidence based medicine only works properly when you can see all the evidence.

Dr Tom Jefferson, Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine

But when the principle of transparency meets reality of responding to requests for information, how does the EMA measure up?

Dr Tom Jefferson, an honorary research fellow at Oxford's Centre for Evidence based medicine and Dr Peter Doshi, assistant professor of pharmaceutical health services research at the University of Maryland, have published a paper in the journal Trials that takes an in depth look at 12 requests for data made to the EMA.

Tom Jefferson explains: 'Policy 0043 has been revolutionary. In previous studies we did show millions of pages of regulatory data have been released. But these analyses only gave a high-level view of how the system was working. If you're trying to get information on a particular drug or a particular trial, what's important is what you are going to get and how long it takes.'

Response times are getting longer, the output seems to be slowing down and bureaucracy is gaining the upper hand.

Dr Peter Doshi, University of Maryland

The 12 EMA data requests were for 118,000 pages relating to 29 medicines and biologics from 2011 to 2015. This included the 2011 request for Tamiflu data by the pair that enabled a Cochrane review to begin to consider the detailed clinical study reports that regulators routinely use to understand and assess trials.

The researchers admit that their study based on a case series is not the ideal way to look at how the regulator is operating its open data policy. But practical limitations meant that it was the best approach they could take. What the series reveals is that the EMA's commitment to openness may be struggling in the face of everyday realities.

Dr Peter Doshi says: 'Our study showed that response times are getting longer, the output seems to be slowing down and bureaucracy is gaining the upper hand. It shows the way it has been for us for the last 5 years. We know from informal contacts with other researchers that things for some of them are even worse, bewildered by a new lexicon and showered with letters written in EMA bureaucratese.'

The system may be slow, but surely it's still better than what's available anywhere else?

Dr Jefferson agrees: ‘We are not trying to damage EMA with this paper. We are pointing out the current difficulties because we believe the EMA policy is the way forward.

'With evidence of reporting bias in the way studies are presented in journals and even suppressed studies when results don't support the desired outcome, open data is vital. As it stands, it is probably the only way forward for Evidence Based Medicine to regain credibility. Evidence based medicine only works properly when you can see all the evidence.

We are pointing out the current difficulties because we believe the EMA policy is the way forward.

Dr Tom Jefferson, Centre for Evidence Based Medicine

The EMA is trying to do the right thing for science, for medicine and especially for the patients they serve. That is precisely why it is worth fighting to improve EMA practice.

Dr Peter Doshi, University of Maryland

'Given the growing recognition of regulatory data as the key to unlocking reporting bias in the scientific literature, the EMA's system needs to be straightforward. Instead, we report that using it is more complex and convoluted than one might hope. There are also signs of a system that must throttle its output to cope with demands. In 2010, the EMA had a team of five people who handled these requests as just part of their job. At the end of 2014 there was a full-time team of 12. In the first two years, there were around 20 requests for data each month. In the six months after that, requests doubled, yet the number of pages of data released fell by more than a third.'

Now, the EMA has a new policy – 0070 – which aims to openly publish trials data, rather than respond to individual requests. However, the documents that appear will be redacted – that is, certain information will be blanked out – and Drs Doshi and Jefferson warn that such redaction may be excessive, meaning that the new policy may not deliver as well the current, albeit imperfectly operating, policy 0043.

Dr Peter Doshi concludes: 'The EMA is trying to do the right thing for science, for medicine and especially for the patients they serve. That is precisely why it is worth fighting to improve EMA practice, perhaps with more resources and regular open audits.'

Canada is now looking at a similar data access scheme and campaigners across the world are determined to get more regulators to be more transparent in an effort to make medicine safer and more effective for all. The lessons that the researchers have identified in their critique of the EMA's pioneering approach may be just as useful outside Europe as within it.

As a philosophical and practical concept, the idea of the division of labour – the separation of a work process into a number of tasks – can be traced back through figures as eminent as the economist Adam Smith and the engineer Charles Babbage (and even to a passage in Plato's Republic).

But while the division of labour is most commonly associated with mass production assembly lines, a new paper from researchers in Oxford University's Department of Zoology shows how bacteria can evolve a similar process in a matter of days.

Dr Wook Kim, first author of the study, published in Nature Communications, told Science Blog: 'Many sophisticated societies have the division of labour – not least our own, where it is central to much of our success both ecologically and industrially. Indeed, the term was used by the Scottish economist Adam Smith, who was a major player in the industrial revolution. Smith originally applied it to the idea of factory production lines, where different people specialise on individual tasks to manufacture something more complex. Smith wrote about manufacturing pins, but it is in car manufacturing that this process is perhaps best known and used.'

In biology, the division of labour is observed in a number of insect societies – including bees, ants, wasps and termites – in which workers specialise in tasks such as foraging for particular foods, nursing the young, or guarding the colony. This allows the colony to achieve things collectively that a lone individual could never do.

Dr Kim added: 'As well as insects, the division of labour is also known from a few species of bacteria that divide up their cells into specialised cells that do different things. There are a number of tasks divided up in this way, including toxin production, DNA uptake, and spore formation. However, in all cases, these systems have taken a long time – presumably millions of years – to evolve. By contrast, we have found that bacteria can evolve a division of labour in a matter of days. This opens up the possibility that the division of labour is much more widespread than we realised and is a way that many bacteria can deal with new challenges they face in the environment.'

Based on the knowledge that bacteria can evolve rapidly in response to environmental challenges, Dr Kim and colleagues, including senior author Professor Kevin Foster, turned their attention to the division of labour.

Dr Kim said: 'We observed that colonies of Pseudomonas fluorescens repeatedly evolved to spread out rapidly and gain new territory much more successfully than their ancestors. Moreover, we found that this territory-grabbing is done by the combination of two genotypes working together – a division of labour. One strain pushes from behind, and the other makes a wetting polymer that lubricates and allows them both to move outwards. So it's a really nice mechanical division of labour, where together they can do something that neither can do on their own. We also show that this all occurs with just a single mutation that makes the "pushy" strain more sticky and adhesive. This allows it to form a rigid mat behind the other strain and push it along.

'Given the propensity of bacteria to rapidly radiate – or evolve – in every environment, this process should effectively create many combinations and permutations of distinct genotypes that may lead to a division of labour. Our work is also testament of the power of evolution, through natural selection, to find elegant solutions to a problem. By simply putting the cells on agar, we inadvertently gave the bacteria the challenge of finding a better way to colonise the surface of the nutrient-rich agar. In the face of this challenge, they rapidly responded to generate this simple but elegant solution that relies on both teamwork and the division of labour.'

- ‹ previous

- 132 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?