Features

Many of us know the feeling of standing in front of a subway map in a strange city, baffled by the multi-coloured web staring back at us and seemingly unable to plot a route from point A to point B.

Now, a team of physicists and mathematicians has attempted to quantify this confusion and find out whether there is a point at which navigating a route through a complex urban transport system exceeds our cognitive limits.

After analysing the world's 15 largest metropolitan transport networks, the researchers estimated that the information limit for planning a trip is around 8 bits. (A 'bit' is a binary digit – the most basic unit of information.)

Additionally, similar to the 'Dunbar number', which estimates a limit to the size of an individual's friendship circle, this cognitive limit for transportation suggests that maps should not consist of more than 250 connection points to be easily readable.

Using journeys with exactly two connections as their basis (that is, visiting four stations in total), the researchers found that navigating transport networks in major cities – including London – can come perilously close to exceeding humans' cognitive powers.

And when further interchanges or other modes of transport – such as buses or trams – are added to the mix, the complexity of networks can rise well above the 8-bit threshold. The researchers demonstrated this using the multi-modal transportation networks from New York City, Tokyo, and Paris.

Mason Porter, Professor of Nonlinear and Complex Systems in the Mathematical Institute at the University of Oxford, said: 'Human cognitive capacity is limited, and cities and their transportation networks have grown to the point where they have reached a level of complexity that is beyond human processing capability to navigate around them. In particular, the search for a simplest path becomes inefficient when multiple modes of transport are involved and when a transportation system has too many interconnections.'

Professor Porter added: 'There are so many distractions on these transport maps that it becomes like a game of Where's Waldo?

'Put simply, the maps we currently have need to be rethought and redesigned in many cases. Journey-planner apps of course help, but the maps themselves need to be redesigned.

'We hope that our paper will encourage more experimental investigations on cognitive limits in navigation in cities.'

The research – a collaboration between the University of Oxford, Institut de Physique Théorique at CEA-Saclay, and Centre d'Analyse et de Mathématique Sociales at EHESS Paris – is published in the journal Science Advances.

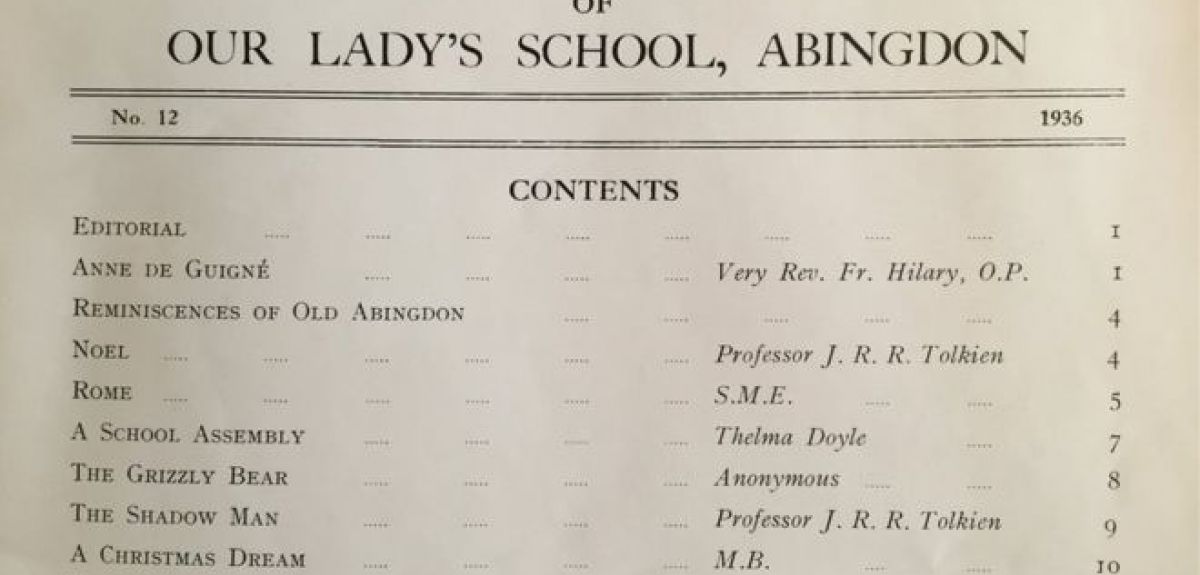

Two poems by author JRR Tolkien have been discovered in a 1936 copy of an Oxfordshire school's annual.

It is believed that Tolkien came to know Our Lady’s School in Abingdon while he was a professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University.

Dr Stuart Lee, a Tolkien expert in Oxford University's English Faculty, says the poems do not add a lot to our understanding of Tolkien but that "it is always fascinating to see previously unknown material".

'Tolkien is mainly known as a prose writer through his novels but he also wrote quite a bit of poetry some of which has been published,' he says.

'These two poems are additions, therefore, to a growing area of scholarship around his verse.'

The two poems, published under the name of 'Professor J.R.R. Tolkien', are called The Shadow Man and Noel, the latter of which is a Christmas poem.

'Of the poems Noel is a clear celebration of his Christianity/Catholicism,' explains Dr Lee. 'It shows the transformation of dark to light with the coming of Christ.

'It is still a very Tolkien poem though with archaic/classical imagery (sword/sheath, o’er … dale).

'The Shadow Man is more interesting in some ways as it is like some of his other poems. It suggests a folk-tale origin, but is elusive in its exact provenance, and also quite dark and sinister.'

A year later in 1937, Tolkien's first literary success The Hobbit was published. Dr Lee says The Shadow Man remind him of the poems contained in the Middle Earth books.

'Tolkien wrote a few poems like this which almost feel like the type of poem someone would recite in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings,' he says.

His association with Our Lady's School is also interesting, says Dr Lee, because it shows a prominent professor at Oxford taking the time to visit and support a school.

'It shows how generous Tolkien was,' says Dr Lee. 'He is noted as doing a lot of talks for local schools, and this is yet another example (albeit early) of Oxford’s outreach approach!'

It has been known for some time that plant roots can communicate with plant shoots. Now, a new paper from Oxford researchers (working in collaboration with researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing) tells us how.

Professor Nick Harberd, Sibthorpian Professor of Plant Sciences at Oxford, spoke to Science Blog about the work.

'The fact that plant roots communicate with plant shoots is in many ways not surprising. Plant shoots incorporate carbon (as CO2) from the air, while plant roots extract mineral nutrients (for example, nitrate or phosphate) from the soil. Coordination of these activities is likely to be selectively advantageous, because it enables the whole plant to optimize its metabolism and growth. But the mechanism of communication has, until recently, been relatively unknown.

'Our paper shows that communication is achieved via movement of an agent from shoot to root. This agent is a protein known as HY5, a kind of protein known as a "transcription factor" that can activate, or "switch on", genes. HY5 was already known to control rates of photosynthesis (CO2 capture) in the shoot. Our work shows that HY5 acts as an agent of communication between shoot and root by moving through the phloem vessels (part of the plant vascular system).

'HY5 travels from shoot to root, and when it reaches the root it activates a number of genes in root cells, including those genes that encode the nitrate transporters that extract nitrate from the soil. This activation is also dependent upon sugars (a measure of CO2 capture) that also travel through the phloem from shoot to root. Thus, movement of HY5 and sugars from shoot to root increases nitrate uptake by the root.

'Our use of genetics in this research has enabled us to discover things previously unknown. We screened for mutants that had reduced shoot-root communication. The logic here is that the mutants would lack genes that controlled shoot-root communication, thus allowing us to identify the genes which, in normal plants, control that communication. One of our mutants identified a gene encoding the previously well-characterised HY5 protein. What we discovered using this technique was that HY5 moves from shoot to root, something new that hadn’t previously been known to be a property of HY5.

'In terms of fundamental science, this new knowledge significantly advances our understanding of how plant shoots and roots communicate with one another, and especially how that communication coordinates whole-plant growth and metabolism. This is just the beginning of what is likely to become a major new area in fundamental plant biology.

'In terms of application, HY5 was first identified as a protein that regulates the growth of plants in response to light signals. Most crops (for example, wheat, rice or maize) are grown in relatively dense plantings in which individual plants tend to shade one another. Our findings mean that HY5 can now become a target for breeders to increase HY5 activity in the roots of shaded crop plants, thus improving uptake of nitrate from the soil.

'This is a major objective for plant breeders worldwide as it will increase the efficiency with which crops use fertilizer, reduce the damaging ecological impacts of fertilizer run-off from fields, and in general contribute to the environmentally sustainable increases in crop yields that we need to feed the growing world population.'

The paper 'Shoot-to-Root Mobile Transcription Factor HY5 Coordinates Plant Carbon and Nitrogen Acquisition' is published in Current Biology.

'Valentine's Day' has not always had the same romantic connotations that it has today.

In a guest post, Dr Huw Grange, Junior Research Fellow in French and Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, explains its origins:

If you’d asked someone to be your Valentine before the 14th century, they'd probably have looked at you as if you were mad. And checked you weren't holding an axe.

There were two saints by the name of Valentine who were venerated on February 14 during the Middle Ages. Both Valentines were supposedly Christian priests who fell foul of Roman officials keen on decapitation.

But there's little in the early legends of either saint to suggest a highly successful posthumous career as assistant Cupid. So I wouldn't go to them for tips.

It was probably Geoffrey Chaucer who got the Valentine’s ball rolling. In his Parliament of Fowls, Chaucer imagined the goddess Nature pairing off all the birds for the year to come on “Seint Valentynes day”.

First up is the queenly eagle. She's wooed at great length by noble birds-of-prey, much to the annoyance of the ducks and cuckoos and other low-ranking birds (eager to get on with getting it on):

‘Come on!’ they cried, ‘Alas, you us offend!

When will your cursed pleading have an end?’

Amid impatient squawks rivalling our very own Prime Minister’s Questions (“Kek kek! kokkow! quek quek!”), the she-eagle can’t decide which suitor most deserves her love. So she resolves to keep ’em keen till the following year.

But why on earth did Chaucer pick a date in February for his avian assembly? England’s birds aren’t exactly in full voice at this time of year, even with global warming. Perhaps he was thinking of an obscure St Valentine celebrated in Genoa in the month of May.

But the Valentines fêted on February 14 were better-known, and that was the date that stuck. Of course, when it comes to matters of the heart, we can hardly expect reason to triumph.

Fiction to fact

Murky origins didn’t matter for too long, however. By the turn of the 15th century, fictional lovebirds weren’t the only ones singing their hearts out on Valentine's day.

According to its founding charter, a society known as the “Court of Love” was set up in France in 1400 as a distraction from a particularly nasty bout of plague. This curious document stipulates that every February 14: “when the little birds resume their sweet song” (sure about that, guys?), members should meet in Paris for a splendid supper.

Male guests were to bring a love song of their own composition, to be judged by an all-female panel. More effort than Tinder demands, then. But if you want to make an effort…

There's no evidence that the Court of Love convened as often as planned (its charter provided for monthly meetings in addition to February 14 festivities). But nor does it seem to have been pure poetic fiction. Eventually totalling 950 or so, participants represented quite a cross-section of society, from the king of France to the petite bourgeoisie. Valentine’s day romance was no longer just for the eagles.

Today's February 14 love-fest, then, is perhaps the result of a group of medieval men and women making life imitate art. If so, their mimicry wasn’t necessarily naïve.

By staging the most poetic of avian courtship rituals, Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls prompts its audiences to ponder the differences between their “artistic” courtship and the birds’ “natural” one.

Texts like this one helped medieval audiences understand their identities as the product of cultural artefacts. And in this regard they can still help us today.

Four medieval tips

On a more practical note, medieval literature can be of assistance if you’re yet to find a gift for a special someone this Valentine’s day. Forget about flashy jewellery; here are some love tokens suitable for every budget:

Looking to reignite that spark in your relationship? In his 12th-century Art of Courtly Love Andreas Capellanus suggests buying your partner a washbasin. Who needs expensive perfume when a good wash may do the trick?

How about personalising some of your beloved’s clothes? Add fasteners only you know how to undo and you’ve got yourself an instant chastity belt. (See the 12th-century tales by Marie de France for examples of suitable garments.)

Alternatively, upcycle one of your lover’s old shirts by sewing strands of your hair into it. To judge by Alexander’s reaction in the 12th-century romance of Cligés by Chrétien de Troyes, they’ll never want to wear anything else. (Hand-wash only.)

And if the above just don’t seem heartfelt enough, you could always take a leaf out of Le Chastelain de Couci’s book, who (according to his 13th-century biography) literally gave his heart to his lover. (Beware unwanted side effects.)

Top tip: provide a little literary and historical context with the above gifts and there's even a chance your Valentine won't look at you as if you're holding an axe.

Dr Huw Grange's piece also appeared in The Conversation.

The Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) has today announced £9m of funding – known as the Healthcare Technologies Challenge Awards – to be shared among research projects that promise to improve healthcare diagnosis and treatment across a wide range of issues. Life Sciences Minister George Freeman described the projects as 'innovative' and 'game-changing', illustrating why the UK is a world leader in life sciences.

Two of the winning projects are based in the University of Oxford's Department of Engineering Science. The project leaders spoke to Science Blog about their work.

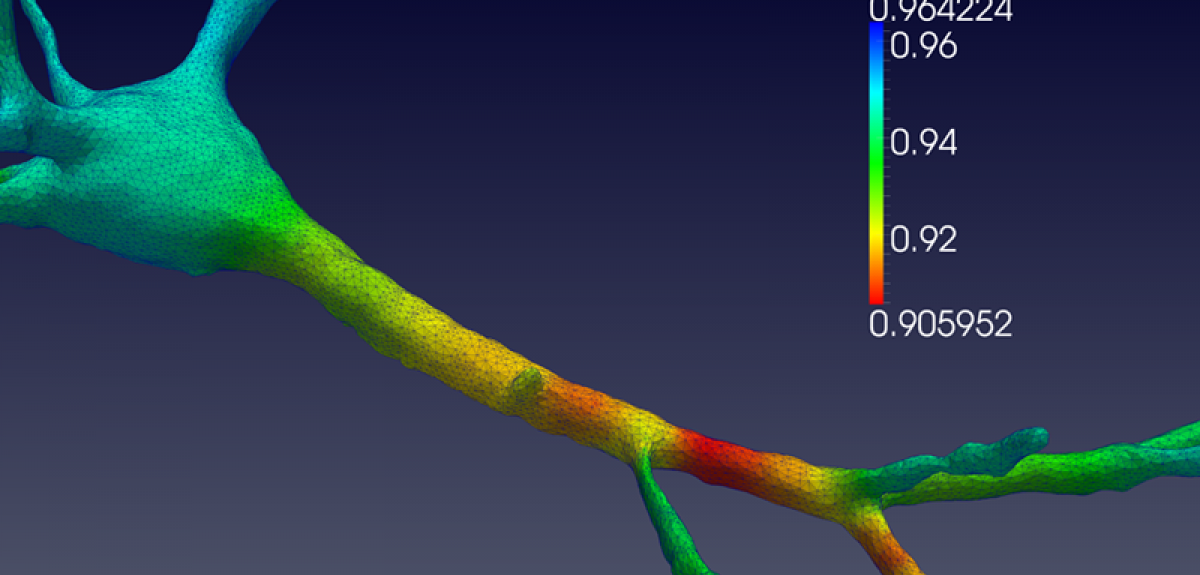

Professor Antoine Jérusalem: 'Electrophysiological-mechanical coupled pulses in neural membranes: a new paradigm for clinical therapy of SCI and TBI (NeuroPulse)'

'Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major public health issue, with over 10 million incidents resulting in death or hospitalisation globally each year. The World Health Organization estimates that TBI will surpass many diseases as the major cause of death and disability by 2020. The other constituent of the central nervous system is the spinal cord. Damage to the spinal cord, or spinal cord injury (SCI), shares many similarities with TBI but can lead independently to pain and/or motor impairments ranging from incontinence to paralysis. Pain management – a direct consequence of TBI and SCI but much wider in scope – is quietly emerging as one of the most important healthcare costs in the UK.

'The recent increase in the number of research campaigns on TBI and SCI has drastically improved the understanding of the coupled role of micromechanics and electrophysiology at the neuron level. However, the intrinsic relationship between mechanical vibrations and their biophysical implications is still widely ignored in this context. As a direct consequence, the effect of functional alteration due to a mechanical insult on the vibrational mechanical properties of a neuron has so far been ignored.

'NeuroPulse thus aims at developing and utilising state-of-the-art modelling approaches for the study of electrophysiological and mechanical coupling in a healthy and mechanically damaged axon, nerve and, eventually, spinal cord and brain white-matter tract. The resulting in-silico platform will be calibrated and validated by means of a comprehensive experimental programme in collaboration with the Department of Physics at Oxford, via co-investigator Professor Sonia Contera. Two teams of clinical project partners in Oxford and Cambridge will participate in the analysis of the results for direct applications in a clinical setting. The clinical support for the research at Oxford will be provided by Dr Damian Jenkins and Mr Tim Lawrence of Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

'NeuroPulse encompasses three of the four pillars of the Healthcare Technologies Grand Challenges: a) the development of future therapies aimed at leveraging neuron electrophysiological-mechanical coupling to modify or quantify electrophysiological properties through control of the mechanical properties; b) treatment optimisation by non-invasive mechanically based pain treatment and functional deficit detection; and c) transforming community health and care by alleviating the need for primary care to "second guess" a patient's symptoms (as is unfortunately often the case in TBI), and by providing an objective roadmap for damage quantification.

'In doing so, NeuroPulse will help decrease the societal and economic burden of TBI, SCI and pain management in the UK and worldwide.'

Dr David Clifton: 'Machine Learning for Patient-Specific, Predictive Healthcare Technologies via Intelligent Electronic Health Records'

'Healthcare systems worldwide are struggling to cope with the demands of ever-increasing populations in the 21st century, where the effects of increased life expectancy and the demands of modern lifestyles have created an unsustainable social and financial burden. However, healthcare is also entering a new, exciting phase that promises the change required to meet these challenges: ever-increasing quantities of complex data concerning all aspects of patient care are being routinely acquired and stored throughout the life of a patient. These datasets include the electronic health records (EHRs) now active in many hospitals, as well as data from patient-worn sensors.

'The dramatic growth in data quantities far outpaces the capability of clinical experts to cope, resulting in a so-called "data deluge" in which the data are largely unexploited. There is huge potential for using advances in big-data machine learning to exploit the contents of these complex datasets by performing robust, automated inference at very large scales. This promises to improve healthcare outcomes significantly by allowing the development of patient-specific healthcare technologies, a field in which there is little existing research.

'The Oxford project, based in the Computational Health Informatics Laboratory and collaborating closely with the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, will tackle two main problems.

'First, there is a global need for reliable, continuous monitoring of patients in healthcare systems, both in hospitals and hospital-at-home settings. The majority of patients, though, are ambulatory and unmonitored, and, consequently, there is an unacceptably high rate of mortality and morbidity. However, existing monitoring systems are simplistic, have very high false alarm rates, and are not predictive. We will develop a suite of technologies that exploit the very large quantities of largely unused data, enabling clinicians to have early warning of patient deterioration via monitoring systems that forecast patient health in a robust manner, using machine-learning methods.

'Second is the idea that infectious disease is as great a threat to national security as climate change. Existing lab-based methods for testing for infectious disease can take up to six weeks to perform. However, whole-genome analysis (of bacterial DNA) combined with machine learning across the EHR could be performed almost on the same day, greatly improving our ability to identify and fight outbreaks of infectious disease. Here, the engineering challenge is to develop probabilistic models to identify novel relationships between the massively multivariate genomic data of the pathogen (the genotype) and the corresponding patient data from the EHR (the phenotype). In this second theme, we will improve our understanding of infectious disease, and, working with Public Health England, will provide systems that predict resistance to antibiotic drugs so that patients are given the right drugs at the right time. The changing nature of drug resistance is a serious problem for the way we deliver healthcare, and machine-learning systems that can "evolve" their understanding of resistance through time are of particular importance.'

- ‹ previous

- 131 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?