Features

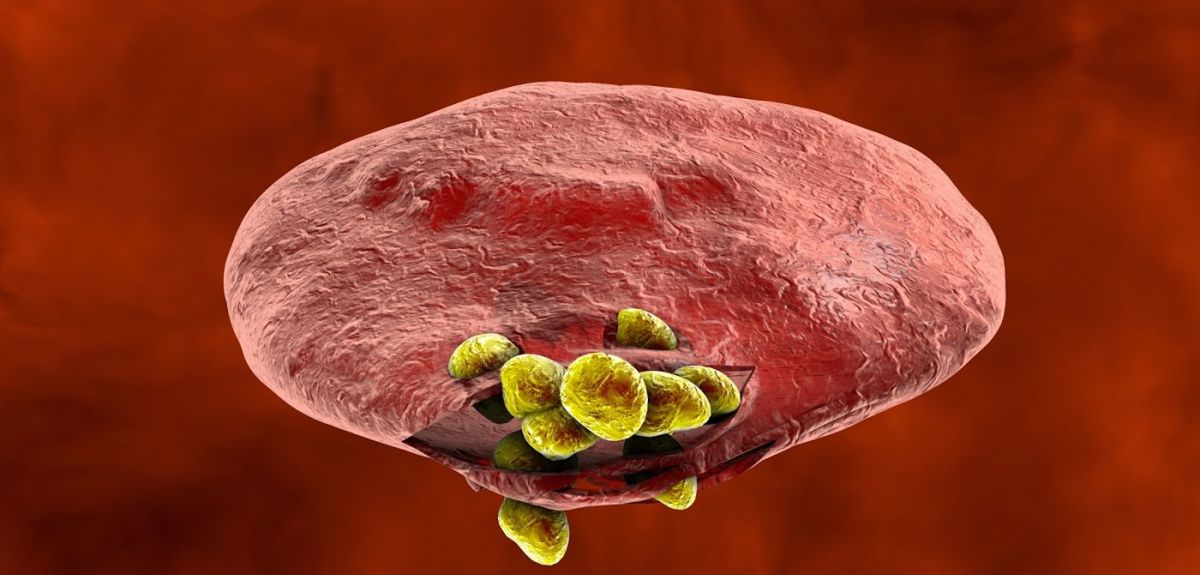

Despite huge efforts to treat and eradicate the disease, in 2015, 214 million people were infected with malaria. 438,000 died. More than 292,000 of those deaths were African children aged under five. Treatment is complicated by the fact the malaria parasite develops resistance to anti-malarial drugs.

Oxford researchers are looking for new ways to target malaria, including vaccines and drugs, but the answer may lie in genes – our genes, the parasite’s genes and even those of the mosquito that carries it. A team based in Oxford and at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, just outside Cambridge, are working together with scientists and clinicians in more than 40 malaria-endemic countries to integrate epidemiology with genome science.

This is the Malaria Genomic Epidemiology Network (MalariaGEN), a global researcher community aiming to understand the genetic diversity in the human host, the parasite and the mosquito vector.

In the second of two interviews about research from MalariaGEN, we look at a study published in eLife, which looks at the genetics underlying the developing resistance to artemisinin.

Central to this is something called kelch13, so when I spoke to Dr Roberto Amato, I started by asking what that is…

This gene [kelch13] is highly conserved in the Plasmodium genus; its DNA sequence has remained nearly unchanged for more than 50 million years.

Dr Roberto Amato, Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics

Roberto Amato: kelch13 is one of the ‘nicknames’ of a gene officially known as 'PF3D7_1343700' in the malaria-causing parasite Plasmodium falciparum. The gene sits more or less in the middle of chromosome 13 and contains a particular sequence which is found in many species including humans, the 'kelch motif' – hence the name 'kelch13'.

This gene is highly conserved in the Plasmodium genus; its DNA sequence has remained nearly unchanged for more than 50 million years.

The gene has been the focus of much attention since December 2013, when research led by the Institut Pasteur first associated mutations in this gene, and specifically within the kelch domain, with resistance to artemisinin, the current frontline treatment for uncomplicated malaria.

Since then, several studies have confirmed that this gene plays a crucial role in artemisinin resistance in clinical samples while others have focused on figuring out how the gene works. Much is still unknown but one thing is clear: this is an unusual beast, and a very complicated gene to deal with! In fact, what has gradually emerged is that several mutations to the gene all cause resistance to the drug.

We're fortunate enough to work with researchers in dozens of malaria-endemic countries through the MalariaGEN P. falciparum Community Project. Together, this research network has generated a large — possibly the world's largest — collection of whole genome sequences of P. falciparum parasites.

Dr Roberto Amato, Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics

We know that P. falciparum mutates rapidly, so the question becomes: Why didn’t resistance emerge earlier – and everywhere? It's possible that there is a more complicated story that we have yet to understand.

OSB: This does sound complex. How do you start to make sense of mutations in kelch13?

We decided to study not only this one gene, but to look across the whole parasite genome.

We're fortunate enough to work with researchers in dozens of malaria-endemic countries through the MalariaGEN P. falciparum Community Project. Together, this research network has generated a large — possibly the world's largest — collection of whole genome sequences of P. falciparum parasites. This resource allowed us to scan 3,411 parasite genomes from samples collected in 23 countries.

This large sample size meant that we could 'calibrate' the mutations that we could detect in kelch13 against other genes with similar levels of conservation. This is important because there are few observable mutations in highly-conserved genes, so we need large sample sizes to find enough genetic changes to achieve adequate statistical power.

In particular, we want to compare the mutations present in Southeast Asia, where artemisinin resistance has been reported in several countries, with Africa, where malaria transmission rates are highest but, as far as we know, there aren't yet signs of clinical resistance.

We found three interesting differences between the genetic variations observed in parasites from these two regions:

Firstly, we showed that some of the key mutations associated with artemisinin resistance in Southeast Asia, most notably C580Y, are already present in Africa.

Previous studies have shown that mutations in kelch13, and in particular in the kelch domain, were present in Africa. However, these were different mutations than those found to be associated with artemisinin resistance in Southeast Asia. This gave rise to the suspicion that 'not all mutations are created equal'. While this might well be true, our results challenge this hypothesis — and highlight once again the complexity of the intricate (and intriguing) story of artemisinin resistance.

Secondly, these key mutations associated with artemisinin resistance in Southeast Asia are less common in African parasites.

Using our large data set, we were able to determine what constitutes a 'physiological' level of variation that is consistent with our expectations – essentially, how common we'd expect these mutations to be in the absence of a selective pressure. This is what we observe in African samples, but the key kelch13 mutations are far more common in Southeast Asia. This is an intriguing difference which I'll come back to in a moment.

We think that 'something' allows kelch13 mutations to occur more often in Southeast Asia but not in Africa. We don't know what that something is, but we have some ideas—and these hypotheses are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Dr Roberto Amato, Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics

Thirdly, in Southeast Asia, we observed more non-synonymous mutations than what we expected, but not in Africa.

OSB: What might be the reasons for these differences?

RA: Non-synonymous mutations are interesting because they have the potential to produce drastic changes to the protein and the way it works (in contrast with synonymous mutations that have no effect on the resulting protein). For this reason, non-synonymous mutations are typically less common in highly-conserved regions like kelch13. Their unusually high presence in Southeast Asia suggests that there is a reason, possibly a selective pressure, driving this pattern of genetic variation.

We think that 'something' allows kelch13 mutations to occur more often in Southeast Asia but not in Africa. We don't know what that something is, but we have some ideas—and these hypotheses are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

For example, drug pressure in Africa is not as sustained as in Southeast Asia and it might not be sufficient to counterbalance the likely fitness cost of kelch13 mutations – don't forget that if kelch13 has remained nearly unchanged for so long, there must be a reason! This lack of selective pressure could be because access to artemisinin in Africa is more recent and still limited. But it may also have to do with the acquired immunity that adults often develop in regions where malaria is common. In high-transmission areas, such as Africa, people may become infected without realising it. The result is a large reservoir of parasites that are not exposed to antimalarial drugs because individuals without symptoms do not seek treatment.

Another possibility is that other changes in the parasite genome have emerged in Southeast Asia, but not yet in Africa, to compensate potential deleterious effects of kelch13 mutations. Some evidence for this is provided by our earlier paper in Nature Genetics.

OSB: What does this mean for malaria control?

RA: Artemisinin resistance has been reported in several countries in Southeast Asia, which is leading to increased interventions in many of the affected areas. If artemisinin resistance were to become established in Africa (either through spread or independent emergence), where malaria transmission is highest, it could trigger a public health crisis.

Our study is an important reminder that malaria control interventions, like the administration of drug treatments, create a changing 'environment' – from the parasites' point of view, what we call drug resistance is simply adaptation to a new environment. Malaria parasites have proved tremendously good at that: resistance has emerged to every antimalarial drug used to date! Through this lens, drug administration can be seen as a large-scale evolutionary experiment.

Monitoring molecular markers of drug resistance in malaria parasites can help to track the emergence and spread of drug resistance. Some molecular markers are straightforward to monitor. For example, chloroquine resistance can be rapidly identified by typing a single base change in the crt gene in P. falciparum.

If we are to integrate genomic surveillance into large-scale public health interventions, this would help to increase the resolution of our picture of genetic variation in space and time – and provide a valuable feedback loop of information for malaria control.

Dr Roberto Amato, Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics

What we're seeing is that the signals are much more complex in the case of artemisinin resistance. Our findings suggest that the pattern of genetic diversity in kelch13 is not straightforward, and to use it as a molecular marker means 'contextualising' observed mutations. That in itself is an important message for those considering how molecular studies can help inform malaria control and respond to the challenge of artemisinin resistance.

OSB: What does this research tell us about the future for antimalarial resistance? And the future for the fight against malaria?

RA: If we buy into the idea that drug interventions are evolutionary experiments (at least from the perspective of the parasite) then we should do our best to try to evaluate, and possibly anticipate, the impact of such interventions.

As drug resistance can be extremely complex and dynamic, we need to use every arrow in our quiver to counter it. Genomics is one these arrows. And, not insignificantly, it is also one of the few that allow us to directly observe how the parasite is responding without many of the confounders stated before (e.g. acquired immunity, differences in transmission settings, etc).

If we are to integrate genomic surveillance into large-scale public health interventions, this would help to increase the resolution of our picture of genetic variation in space and time – and provide a valuable feedback loop of information for malaria control.

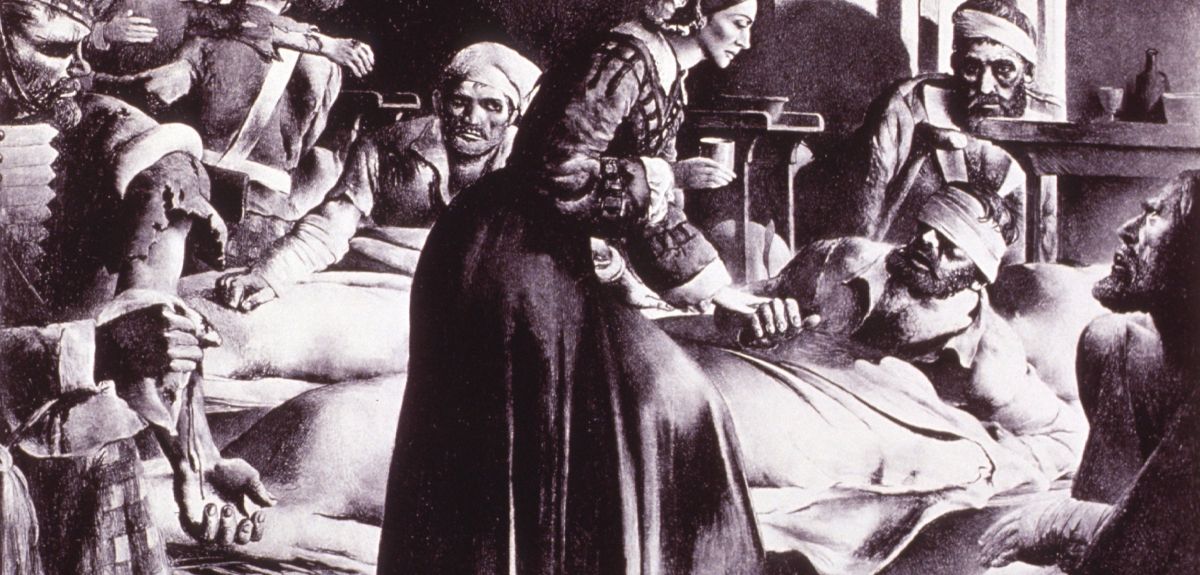

Dr Philip Carter is an Oxford historian and Senior Research and Publication Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB). In a guest post for Arts Blog, he explains a new development in the Oxford DNB: the addition of voice recordings of historical individuals to their biographies.

'For 135 years Oxford’s Dictionary of National Biography has been the national record of noteworthy men and women who’ve shaped the British past. Today’s Dictionary retains many attributes of its Victorian forebear, not least a focus on concise and balanced accounts of individuals from all walks of national history. But there have also been changes in how these life stories are told.

In its Victorian incarnation the Dictionary presented each life as a double-column printed text. Publication of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online, in 2004, saw the addition of portrait images.

Today the Dictionary includes portraits of 11,500 of its 60,000 subjects. Every image is a depiction of the sitter from life, so as to convey an aspect of his or her personality.

Now the Oxford DNB takes the next step - the inclusion of sound - with a project to link biographies to voice recordings made by an initial selection of 750 historical individuals. In doing so, we’ve teamed up with the British Library whose ‘Early Spoken Word’ archive is a trove of documentary clips, oral histories, and music recordings—allowing us to hear historical figures orate, converse, and perform.

Partnerships like this are the way forward for digital reference works. They create interconnections of specialist collections, be they biographies, sound recordings, art works or archive film footage.

'ODNB’s sounds project is the first in a series of collaborations that will see the Dictionary integrated with digitized manuscripts, creative works, television clips, memorials, Blue Plaques, and further voice recordings. In doing so, it draws on content provided by, among others, Art UK, the BBC, English Heritage, the Royal Collection, and Westminster Abbey.

For researchers it’s an opportunity to follow a biography from the traditional written text to more intimate instances and expressions of a life: handwriting and marginalia, movements caught on camera, houses lived in and streets once walked, and of course voices.

It’s the ability to hear historical figures speak—to catch their accents and their intonations— that’s the principal attraction of linking ODNB biographies to sound recordings. Hearing the voice reminds us that a distant historical figure was a living person as well as the subject of a modern biographical text.

The effect is particularly striking in the Oxford DNB’s earliest link to the British Library archive—that for Florence Nightingale who spoke in support of the Light Brigade Relief Fund in July 1890. Barely audible over the hiss, she concludes her short, carefully enunciated message:

‘When I am no longer even a memory, just a name, I hope my voice may perpetuate the great work of my life. God bless my dear old comrades of Balaclava and bring them safe to shore. Florence Nightingale’.'

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is a research and publishing project of Oxford’s History Faculty and Oxford University Press.

Oxford's Rothermere American Institute (RAI) is playing a key role in analysing the US election for a UK audience.

In The Independent last week, Professor Nigel Bowles and Dr Ursula Hackett analysed the chances of Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders.

Tomorrow, on 'Super Tuesday', the RAI will play an even more active role in the election: it will host the polling station for the Democrat Global Presidential Primary from 12pm to 7pm.

The Global Presidential Primary is a key element in the Democrat primary process. At stake are 21 delegates (similar in size to the state delegations of Wyoming and Alaska) that will help decide the party's nominee.

One of the high-profile US citizens casting their vote at the Oxford polling station will be Larry Sanders - the brother of Democrat hopeful Bernie Sanders. Mr Sanders will available at midday for interviews.

Expatriate voters have played a decisive role in the outcome of several key political contests in the US - including the 2000 Presidential election, according to a new report from the RAI.

Republicans Overseas, who will also be present for a panel discussion at the RAI event, does not offer a comparable global primary or formal representation at the party convention for registered Republican expat voters (though Republicans can vote in their home state primaries through absentee ballots, as can Democrats who choose this option rather than participating in the Democratic Global Primary).

It appears that overseas Republican voters differ from those in the United States. A recent Republican Overseas poll showed less support for Donald Trump than in the US. The leading candidate among expat Republicans was Marco Rubio.

Professor Jay Sexton, Director of the RAI, said: 'Both the Democrats and the Republicans should not be complacent about the importance of US overseas voters. For the Democrats in particular, these voters will help to determine both the Clinton vs. Sanders primary on Super Tuesday and the general election in November.

'But it's not just the primaries where these American expats should be taken seriously. Overseas voting was critical to putting George W. Bush into the White House in 2000, and if things are tight, could be just as important in the 2016 election too.

'As our report shows, candidates – and parties – ignore overseas voters at their peril.'

As part of the day's activities, the RAI will host a panel discussion entitled 'The Mobilization of Voters Overseas' at 12.30pm. Professor Sexton will moderate discussion between Bill Barnard of Democrats Abroad and Stacy Hilliard, former Vice-Chair of Republicans Abroad.

Oxford University scientists carry out clinical trials for a range of medical conditions every year. The hope with each one is that it could lead to a viable treatment to cure or alleviate that condition. It is easy, therefore, to think that a successful trial is one that produces such a treatment, while any other result is a failure. Not so, as a recent study from Oxford's researchers in South East Asia shows.

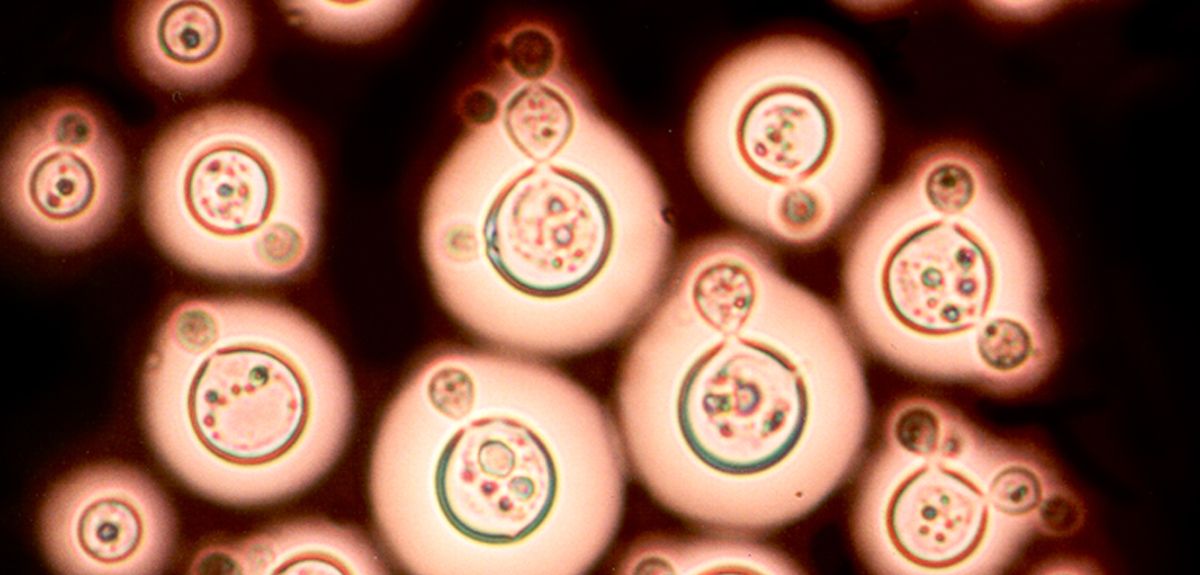

Cryptococcal meningitis is a fungal infection of the brain, which primarily affects people living with HIV. The disease is estimated to cause over 600,000 deaths each year, with the majority of cases occurring in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

Dexamethasone is already being used by some doctors as a treatment for cryptococcal meningitis. They are doing that with the best of intentions, believing it will benefit their patients. However, our trial has shown that that is in fact worse than standard treatment.

Dr Justin Beardsley, Oxford University Clinical Research Unit

Recent research has shown the best way to use the available anti-fungal therapies, but even with optimal treatment, between 3 and 7 out of every ten people affected will die in areas where the disease is most prevalent. The Oxford team therefore studied what happened when an extra drug was given alongside anti-fungal treatments.

Dr Justin Beardsley led the study. He explains: 'Given the relatively poor success rate for existing anti-fungals and the fact that there are no new anti-fungal drugs in the pipeline we decided to trial an adjunctive treatment to reduce HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis' unacceptably high rates of death and disability. An adjunctive treatment is something given to patients to improve the effectiveness of their primary treatment – in this case, the anti-fungal drugs.'

The team selected a steroid called dexamethasone as the adjunctive agent. It had shown promise in observational studies and lab-based animal models and has proven efficacy in some other forms of meningitis. It is also a well-understood drug which hadn't been associated with adverse events when used to treat infectious diseases. Furthermore, despite a lack of evidence, it is already frequently used to treat cryptococcal meningitis.

For the trial, volunteers with cryptococcal meningitis were given either dexamethasone or placebo alongside the standard antifungal therapy. The volunteer patients were in Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Laos, Uganda and Malawi. Each was carefully monitored to see the microbiological and clinical responses to treatment.

The trial was stopped, because the team recognised that outcomes were worse for patients receiving dexamethasone: while they were no more likely to die than those receiving placebo, their infection cleared more slowly, they had more treatment complications and they were less likely to recover without disability.

So is this a failure?

The clinical trial has ended but our work is ongoing.

Dr Justin Beardsley, Oxford University Clinical Research Unit

Dr Beardsley explains that success in a clinical trial is a definitive result. A definite 'yes' is wonderful but a definite 'no' means you can stop researching a treatment that will be ineffective and focus efforts elsewhere. In this case, there is an added and immediate benefit for current patients:

'Dexamethasone is already being used by some doctors as a treatment for cryptococcal meningitis. They are doing that with the best of intentions, believing it will benefit their patients. However, our trial has shown that that is in fact worse than standard treatment. Our evidence will inform those doctors so they know to stop using a potentially harmful treatment.

'It is also important to note that we don't simply record whether something works or not. Samples from patients are analysed and studied, offering huge amounts of data. The clinical trial has ended but our work is ongoing. It should reveal more details about how the immune system responds to cryptococcal meningitis. In turn, those insights may deliver future breakthroughs in the treatment of this deadly and neglected condition.'

It’s worth remembering: Even apparently negative results contribute to positive improvements in healthcare.

Researchers have shed light on a critical paradox of modern medical research – why research is getting more expensive even though the cost and speed of carrying out many elements of studies has fallen hugely. In a paper in journal PLOS ONE, they suggest that improvements in research efficiency are being outweighed by accompanying reductions in effectiveness.

Faster, better, cheaper

Modern DNA sequencing is more than a billion times faster than the original 1970s sequencers. Modern chemistry means a single chemist can create around 800 times more molecules to test as possible treatments as they could in the early 1980s. X-ray crystallography takes around a thousandth of the time it did in the mid-1960s. Almost every research technique is faster or cheaper – or faster and cheaper – than ever.

Added to that are techniques unavailable to previous generations of researchers – like transgenic mice, or computer-based virtual models underpinned by processing power that itself gets more powerful and less expensive every year.

Lower costs yet higher budgets?

So why has the cost of getting a single drug to market doubled around every nine years since 1950? To put that into context, for every million pounds spent on drug research in 1950, in 2010, despite all the advances in speed and all the reductions in individual costs, you needed to spend around £128,000,000 to achieve similar success.

Those figures may explain why research in certain areas has stalled. For example, in the forty years between 1930 and 1970, ten classes of antibiotics were introduced. In the forty-five years since 1970, there have been just two.

Better engine, worse compass

This question is tackled by two researchers in a paper published in journal PLOS ONE, including Dr Jack Scannell, an associate of the joint Oxford University-UCL Centre for the Advancement of Sustainable Medical Innovation (CASMI).

Applying a statistical model, they show that what is critical to the overall cost of research is not the brute force efficiency of particular processes but the accuracy of the models being used to assess whether a particular molecule, process or treatment is likely to work.

Dr Scannell explains: 'The issue is how well a model correlates with reality. So if we are looking for a treatment for condition X and we inject molecule A into someone with it and watch to see what happens, that has high correlation in that person – a value of 1. It also has some insurmountable ethical issues, so we use other models. Those include animal testing, experiments on cells in the lab or computer programmes.

A reduction in correlation of 0.1 could offset a ten-fold increase in speed or cost efficiency.

Dr Jack Scannell, Centre for the Advancement of Sustainable Medical Innovation

'None of those will correlate perfectly, but they all tend to be faster and cheaper. Many of these models have been refined to become much faster and cheaper than when initially conceived.

'However, what matters is their predictive value. What we showed was that a reduction in correlation of 0.1 could offset a ten-fold increase in speed or cost efficiency. Let's say we use a model 0.9 correlated with the human outcome and we get 1 useful drug from every 100 compounds tested. In a model with 0.8 correlation, we'd need to test 1000; a 0.7 correlation needs 10,000; a 0.6 correlation needs 100,000 and so on.

'We could compare that to fitting out a speedboat to look for a small island in a big ocean. You spend lots of time tweaking the engine to make the boat faster and faster. But to do that you get a less and less reliable compass. Once you put to sea, you can race around but you'll be racing in the wrong direction more often than not. In the end, a slower boat with a better compass would get there faster.

'In research we've been concentrating on beefing up the engine but neglecting the compass.'

He adds that beyond the straightforward economics of drug discovery, the use of less valid models may also explain why it is getting harder to reproduce published scientific results – the so-called reproducibility crisis. Models with lower predictive values are less likely to reliably generate the same results.

Retiring the super models

There are two possible explanations for this decline in the standard of models.

When the medical problem is solved, the commercial drive is no longer there for drug companies and the scientific-curiosity drive is no longer there for academic researchers.

Dr Jack Scannell, Centre for the Advancement of Sustainable Medical Innovation

Firstly, good models get results. There is no point finding lots of cures for the same disease, so the best models are retired. If you’ve invented the drugs that beat condition X, you don’t need a model to test possible drugs to treat condition X anymore.

Dr Scannell explains: 'An example would be the use of dogs to test stomach acid drugs. That was a model with high correlation and so they found cures for the condition. We now have those drugs. You can buy them over the counter at the chemist, so we don't need the dog model. When the medical problem is solved, the commercial drive is no longer there for drug companies and the scientific-curiosity drive is no longer there for academic researchers.'

The reverse of this is that less accurately predictive models remain in use because they have not yielded a cure, and scientists keep using them for want of anything better.

Secondly, modern models tend to be further removed from living people. Testing chemicals against a single protein in a petri dish can be extremely efficient but, Scannell suggests, the correlation is lower: 'You can screen lots of chemicals at very low cost. However, they fail because their validity is often low. It doesn't matter that you can screen 1,000,000 drug candidates – you've got a huge engine but a terrible compass.'

He cautions that without further research it is not clear how much the issue is caused by having 'used up' the best predictive models or how much it is a case of choosing to use poor predictive models.

Re-aligning the compass

Is it not peculiar that the first useful antibiotic, the sulphanilamide drug prontosil was discovered by Gerhard Domagk in the 1930s from a small screen of available [compounds] (probably no more than several hundred), whereas screens of the current libraries, which include ~10,000,000 compounds overall, have produced nothing at all?

At one level, it is easy to see why efficiency has been prioritised over validity. Activity is easy to measure, simple to report and seductive to present. It is easy to show that you have doubled the number of compounds tested and it sounds like that will get results faster.

But Dr Scannell and his co-author Dr Jim Bosley say that instead we should invest in improving the models we use. They highlight the focus on model quality in environmental science, where the controversy around anthropomorphic global warning has pushed scientists to explain and justify the models they use. They suggest that this approach – known as 'data pedigree' – could be applied in health research as well, suggesting that it should be part of grant-makers' decision processes. That would ensure that researchers would try to fine-tune their compass as much as their engine.

Dr Scannell concludes: 'If we are to harness the power of the incredible efficiency improvements we have seen, we must also be better at directing all that brute-force power. Better processes must be allied to better models in order to generate better results. We are living with the alternative – a high-speed ride that, all too often, goes nowhere fast.'

- ‹ previous

- 130 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?