Features

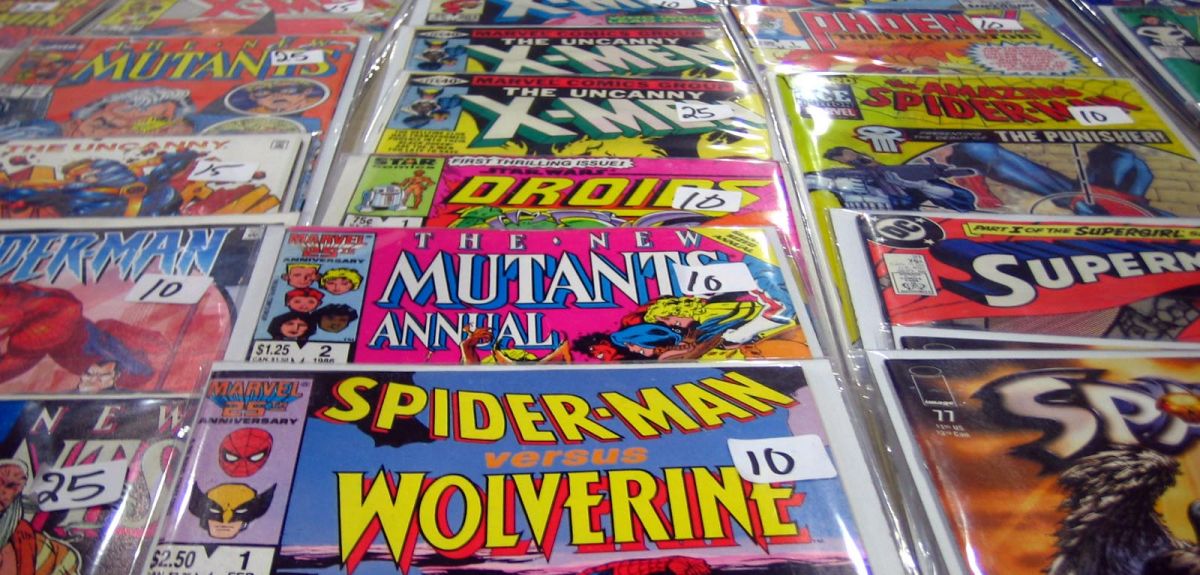

A new research network about comics and graphic novels has been set up by The Oxford Centre for Research in the Humanities (TORCH).

Called ‘Comics and Graphic Novels: The Politics of Form’, the network will look at questions like why comics are not deemed ‘academic’ and whether traditional critical approaches to literature can be applied to comics.

Dr Dominic Davies, a British Academic Postdoctoral Fellow in the English Faculty, has founded the network. He answers our questions about comics:

Have comics been overlooked in academia? Why do you think this might be?

Yes, comics definitely have been overlooked by many academics. This is in part because, by their very nature, they don’t fit easily into the disciplinary structures that we have today. Are they art? Of course, they certainly are, but because they’re usually collected together in strip or book form, circulated in newspapers or sold in bookshops, rather than hung in museums or galleries, it means they’ve often don’t get the attention of art historians and art theorists.

Conversely, are they literature? Many comics look like books, and there are lots of self-labelled comics short stories and ‘graphic novels’. They have a beginning, a middle and an end, and most of them contain text that drives the narrative forward. But they are, also, fundamentally, groupings of sequential images as well as words. The field of literary studies might have the tools to deconstruct comics’ narrative dimensions, but how can literary academics presume to analyse their visual materials? This is one reason that, in its early incarnations at least, comics studies has mostly been located in media studies departments, sometimes even film studies departments.

However, probably the real reason for the slow uptake of comics by academia is that comics have traditionally been seen as a ‘low’ cultural form, one that is filled with coarse language, silly jokes and subversive sentiments and thus not worthy of critical attention. This is especially the case when they are contrasted with the notion of literature, say, as a ‘high’ cultural form with moral worth. This division still haunts comics, even as they have been embraced by academics in recent years, and causes much self-reflexive debate. It was only with the publications of longer comics such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Harvey Pekar’s American Splendour, or Joe Sacco’s Palestine, which move away from conventional superhero stories and tackle complex and serious issues (Spiegelman’s comic is about his father’s time in Auschwitz, for example) that academia started to take them seriously.

So these longer, more obviously ‘serious’ comics, have gained the form recognition in academic circles, and even today academics still tend to focus on them.

Are comics taught in schools and universities? If not, should they be?

Comics mostly aren’t taught in schools. In the U.S., throughout the latter half of the twentieth century when comics production really began to surge, comics were seen not as a medium to help children with their studies, but as distractions—and definitely not something to be studied. This prejudice lingers in education syllabuses today. But there are always exceptions—a comic about anti-apartheid activism is read in schools in Cape Town to educate students about South Africa’s history, for example. And we are seeing comics-only modules cropping up in higher education now.

But this is in large part dependent on whether there is an academic in an English Literature department who happens to have an interest in comics, and the energy to build and offer these modules. One good example is Dr Paul Williams, who has set up a comics-only module at the University of Exeter, and who is coming to give a seminar at our TORCH Network.

As to whether or not comics should be taught in schools and universities, I think the answer is a resounding ‘yes’. The form is so rich, it does so many things that literature or art, as separate mediums, cannot. Indeed, in recent years, there’s been a surge in the kinds of stories that comics are being used to tell—there are now sub-genres within the field, such as autobiographics (autobiographical comics) and comics journalism—and in the popularity of comics, as more and more people find stories they can relate to.

Is there a difference between ‘comics’ and ‘graphic novels’?

That depends on who you ask. As comics have been deemed worthy of academic attention, the term ‘graphic novel’ has become more widely used. This is definitely related to the issue of ‘high’ and ‘low’ forms of culture I mentioned above. The term ‘comics’ is still associated with short strips in newspapers, or superheroes, and these still aren’t really taken seriously. The term ‘graphic novel’ has come to be used by academics to refer to the longer form comic, usually published all in one go as a book – and that is somehow a ‘higher’ cultural form.

It is the term ‘graphic novel’ that high street bookshops such as Waterstones and Blackwell’s use to categorise the comics they sell, and again I think this is related to the idea about what is ‘serious’ literature and worthy of being read by the kinds of people who frequent those stores. While the distinction between the terms ‘comic’ and ‘graphic novel’ has a certain usefulness, there’s a great deal of academic debate about its implicit politics. Graphic novels are still comics, and owe their existence to long histories and rich traditions that extend back into the twentieth century and earlier. Their relabelling as ‘graphic novels’ dismisses this history. Some critics even see the term as being cynically deployed just to make comics more palatable to middle class readerships, academics, and university English departments.

There are numerous other labels that can be used to describe the comics form. I prefer to use the term ‘long-form comics’ rather than ‘graphic novels’ when talking about book-length comics, because it means that we don’t forget the form’s long and valuable history. But it’s important to remember that even under the umbrella term ‘comics’ is a huge diversity of different kinds of reading experience, some of which bear little resemblance to one another.

Discussions around terminologies and definitions have always been at the centre of academic criticism on comics, and these debates are still ongoing, so there’s still no straightforward answer to this question. This Network will include seminars about ‘comics’ and ‘graphic novels’, but will remain self-aware and open to thinking about how these terms are used and what the implications of this usage might be.

Can you apply traditional critical theories to the comic form?

Comics can be analysed with the critical theories that art historians might use, or with other tools from the broader field of visual cultures, such as W.J.T. Mitchell’s work on ‘picture theory’. But since they’re also narratives, literary criticism’s numerous theories such as narratology and discourse, not to mention other fields such as feminist or postcolonial criticism, have a role to play here.

Though comics haven’t had the attention that they deserve from academia, the relatively few critics who have written monographs on them and, in the occasional case, devoted their entire careers to them, have come up with some really sophisticated theories specifically designed for reading comics.

And comics are inherently interdisciplinary, so the tools needed to read them are also interdisciplinary. So it’s really important that our network creates a space for conversations to take place across the traditional disciplinary divides. We’re trying to bring literary critics into dialogue with visual cultures scholars.

And given that the comics and graphic novels we’ll be discussing in the seminars cover such a range of topics, it’s also really important that we welcome historians, geographers, and politics students into the conversation as well. There are also comics being produced in a number of different languages, and so we have committee members from modern languages departments.

How can people get involved and what can we look forward to?

Because the history of comics criticism has always been practiced as much by artists themselves (Will Eisner, Scott McCloud) as it has by academics, we are going to alternate visiting academic speakers with visiting artists to learn more about how actual practitioners go about writing and drawing their comics. So in Michaelmas Term 2016, we have Dr Helen Iball from the University of Leeds talking about autobiographical comics, and Dr Charlotta Salmi from the University of Birmingham presenting some of her recent research on protest and graphic novels in the Middle East.

But we also have some artists coming to present their work and offer their reflections, such as Karrie Fransman, who did a TEDx talk on comics quite recently, and Samir Harb, a geography PhD student at the University of Manchester who is also a published comics artist.

The seminar will run every two weeks throughout term time, and each of these speakers and artists will circulate some comics for participants to read in advance. It’s really important that the Network gets people to actually start reading some comics as well as simply talking and hearing about them.

In addition to the bi-weekly seminars we’ll also have one-off events, in collaboration with other TORCH Networks or other seminar groups based at the university. For example, Jennifer Howell, author of The Algerian War in French-Language Comics (2015), is coming to give a one-off seminar in November 2016.

All will be welcome to attend any of the seminars and talks we’ll be putting on, and we’ll be advertising each event through TORCH, the English Faculty, and various other mailing lists and outlets. In addition, we are currently building up a mailing list of our own, to which you can subscribe by emailing [email protected] or [email protected]. We’ll also be active on social media, so people will soon be able to like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter, and we’ll feature regular blog posts about comics-related topics on the TORCH website as well.

Four years on from the discovery of the Higgs boson, scientists at CERN are seeking your help to find the famous particle’s relatives.

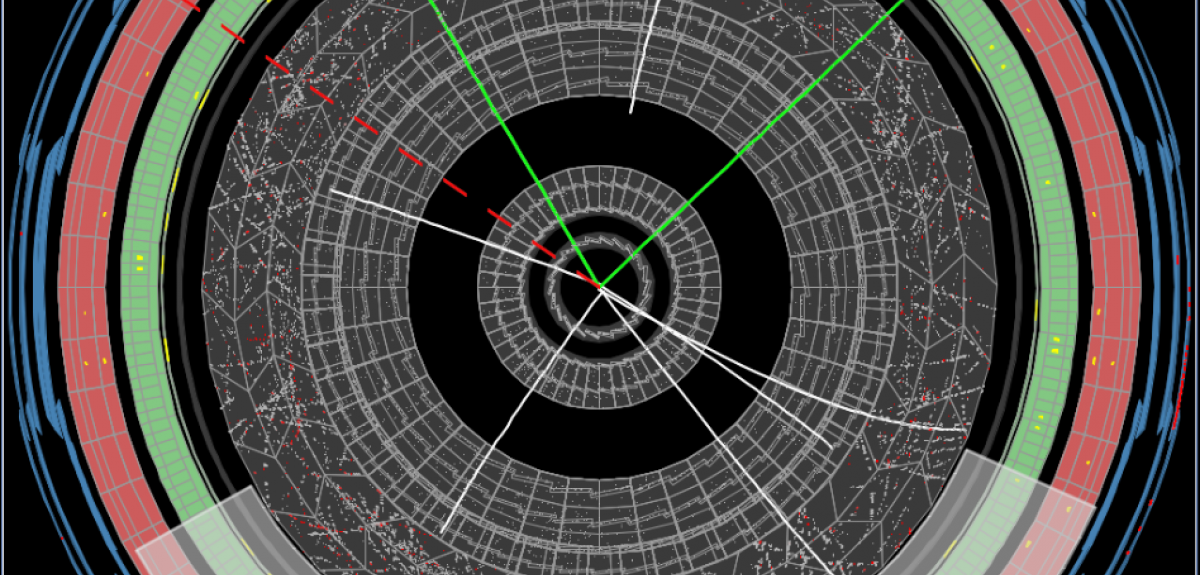

A citizen science project called HiggsHunters is giving members of the public the chance to search through thousands of images from the ATLAS particle detection experiment in the hope of finding 'baby Higgs bosons' – particles that scientists think may come into existence when Higgs bosons break apart.

HiggsHunters, which makes use of the Oxford University-based Zooniverse citizen science platform, has made 60,000 images from the Large Hadron Collider available for analysis. One of the tasks given to participants is to mark anything that looks strange or interesting.

Professor Alan Barr, of Oxford University's Department of Physics, leads the programme. Speaking to The Times, he said: 'This is exactly the sort of image classification problem that the human eye and the human brain are very good at doing, and which computer algorithms might not be well designed for. People are very good at saying, "This one looks very different" or "This is weird".'

One of the 'weird' things that might be found is the baby boson. Professor Barr said: 'There is this new speculative theory that suggests that sometimes the Higgs boson might go pop, giving rise not to things we already know about, but to lighter Higgs bosons – things that are a bit like itself that we have never seen before.

'As Isaac Asimov suggests, the most interesting thing to hear in science is not "Eureka!" but "That looks funny".'

Dr Will Kalderon of Oxford's Department of Physics, who has been working on the project, added: 'We've been astounded both by the number of responses and ability of people to do this so well. I'm really excited to see what we might find.'

In a year when all eyes are on Shakespeare, a new exhibition at the Bodleian Library will explore the life of his friend and rival, Benjamin Jonson.

Jonson (1572-1637) was one of the 17th century’s most influential literary figures, regarded by many in his lifetime as the greatest of all English authors. He remains best known for his satirical comedies Every Man In His Humour, The Alchemist and Volpone.

He led an eventful life, working as a bricklayer and a soldier before becoming a playwright, and has gained a reputation as something of a curmudgeon. He was arrested and tortured for the political content of his work and was suspected of conspiring in the Gunpowder Plot – but even so ended up writing masques for the court of King James I.

The exhibition, named O rare Ben Jonson! and curated by Daniel Starza Smith of the Faculty of English and Nadine Akkerman of Leiden University, celebrates the 400th anniversary of the publication of his Workes.

As well as the Workes, an impressive example of early modern printing, the exhibition will feature sketches and texts for court masques which Jonson worked on, poetry written by Jonson for his friends, and the design for Jonson’s monument in Westminster Abbey – contrary in death as in life, Jonson was buried vertically and upside-down.

'Without Jonson’s Workes we might not have Shakespeare’s First Folio,' says Dr Starza Smith. 'It was very unusual for an author’s collected works to have been published during his own lifetime – that was an accolade reserved for Classical authors.

'Jonson published his own works in the folio format and helped to establish the idea that contemporary drama is suitable for this kind of publication and worthy of praise.'

Also on display are copies of Jonson’s tragic and satirical plays, both offering veiled commentary on the politics of his time. Jonson had a strong sense of what it meant to be a public poet and felt an obligation to confront authority and criticise immorality.

Jonson’s friend William Drummond called him “a great lover and praiser of himself, a contemner and scorner of others”, and his criticism extended to other writers and public figures.

'At one point, Jonson visited Drummond, who got him drunk and wrote down all his gossip about the people they knew, including Shakespeare,' says Dr Starza Smith. 'In fact, it’s mainly due to Jonson that we have an idea of Shakespeare as a person at all.'

Jonson and Shakespeare were good friends as well as rivals: not only did Jonson tell Drummond that he “loved” Shakespeare, he wrote a poem introducing the First Folio, saying of Shakespeare ‘Thou art alive still while thy book doth live’.

The exhibition O rare Ben Jonson! runs until 28th August.

Think of 'an academic' and your stereotype may well include a tendency to wordiness. In truth, while some may live up to that image, academic presentation is usually about distilling information rather than padding it.

Even so, summing up your entire doctorate in three minutes is a challenge. That's about 400 - 500 words, compared to the 80,000 word limit for a doctoral thesis (this blog intro is 185 - or something over a minute). Yet, that's the challenge of the 3 Minute Thesis (3MT), a competition originally developed by The University of Queensland. It aims to cultivate students' academic, presentation, and research communication skills. The competition supports their capacity to effectively explain their research in three minutes, in a language appropriate to a non-specialist audience.

Recently, seven doctoral students from across the University of Oxford competed in the University's 3MT final. Both the winner and runner-up were from Oxford's Medical Sciences Division: Lien Davidson and Tomasz Dobrzycki.

Earlier this week, we published Lien Davidson's 3 Minute Thesis. Now, it's the turn of Tomasz Dobrzycki, a researcher in the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, part of the Radcliffe Department of Medicine.

Tomasz Dobrzycki: Leukaemia research

Last year I registered as a bone marrow donor. If any of you have done it, you know it's a very simple process: you spit in a cup, fill in a form and one day you may save a life.

Although my research may only explain very few of the steps, if the research around the world goes hand in hand, maybe if any of us ever needs a bone marrow transplant, we won't need to wait until somebody spits in a cup.

Tomasz Dobrzycki, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine

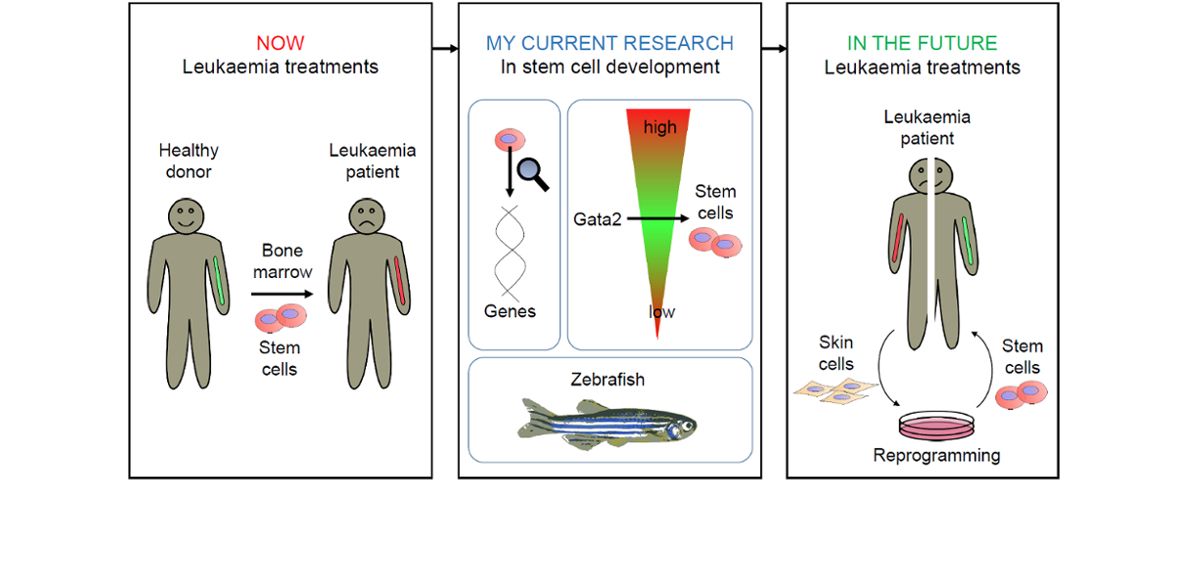

Why? Because the bone marrow contains stem cells that can regenerate a whole blood system and these cells are routinely transplanted to help people with leukaemia.

But here's bad news: It's not always easy to find a perfectly matching donor and so one in three people after receiving the transplant may suffer from life-threatening complications. So rather than getting everyone spitting in a cup, there must be a better way to help.

Imagine if we could take skin cells from the perfect donor – the patient themselves - and play with them in a dish to reprogram them to become very efficient, personalised blood stem cells for transplants – that would be great!

But we can't.

We can't, because we can’t simply make the stem cells with a click of the fingers. The whole process of making a stem cell is more like a marathon run – thousands and thousands of steps. Now each of these steps results from the action of genes, the carriers of information and instructions in our cells, made up of the DNA. The genes have specific roles, they work together and form networks to make sure that every cell appears when and where it has to.

The gene that I’m looking at in my PhD project is called Gata2. Gata2 for the blood stem cell is a bit like food for a marathon runner. If you haven't had enough – you're probably not gonna finish. But if you've eaten too much – you're gonna struggle as well. So I'm investigating why the blood stem cell needs intermediate amounts of Gata2. And to understand this, I'm looking at probably the most natural setting – an embryo that is making the blood stem cells for the first time.

But don't worry – I'm not using human embryos. I'm using fish instead – the zebrafish.

Although the zebrafish looks quite different to us, the way their embryos make blood stem cells is almost exactly the same to the way we do it. So I took my fish, played with their genes and made embryos that have either too little or too much Gata2 and they don't make blood stem cells. And I'm looking at what changes in these embryos to better understand the function of Gata2 and explain its importance in a wider context. The motivation behind it is that maybe one day we'll be able to use this knowledge to recreate the whole stem cell marathon in a dish – step by step.

Although my research may only explain very few of the steps, if the research around the world goes hand in hand, maybe if any of us ever needs a bone marrow transplant, we won't need to wait until somebody spits in a cup.

Hundreds of Tolkien fans, scholars and members of the public flocked to the Weston Library today (23 June) to see a recently-discovered map of Middle-earth.

The exhibition was supposed to be for one day only - but due to popular demand it has now been extended for another day, from 9am-5pm tomorrow (24 June).

As a queue snaked around the Blackwell Hall in the Weston Library and Bodleian staff, the members of staff behind the cafe called it "the biggest queue we have ever seen here".

The map, which is annotated by JRR Tolkien, was acquired by the Libraries earlier this year. Visitors can see Tolkien’s copious notes and markings on the map, which reveal his vision of the creatures, topography and heraldry of his fantasy world where The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings take place.

The map went unseen for decades until October 2015 when Blackwell’s Rare Books in Oxford offered it for sale. It had previously belonged to Pauline Baynes (1922 – 2008), the acclaimed illustrator who was the only artist approved by Tolkien to illustrate his works during his lifetime. The map was a working document that Tolkien and Baynes both annotated in 1969 when Baynes was commissioned to produce a poster map of Middle-earth.

At the time, The Lord of the Rings had never been illustrated so Tolkien was keen to ensure that Middle-earth was accurately depicted. His copious annotations can be seen in green ink or pencil on the map, most notably his comments equating key places in Middle-earth with real world cities, for example that ‘Hobbiton is assumed to be approx. at [the] latitude of Oxford.’

He also specified the colours of the ships to be painted on the poster map and the designs on their sails as well as notes about where animals should appear, writing ‘Elephants appear in the Great battle outside Minas Tirith.’

The map has joined the Bodleian’s Tolkien archive, the largest collection of original Tolkien manuscripts and drawings in the world. It was purchased with assistance from the Victoria & Albert Purchase Grant Fund and the Friends of the Bodleian, and the display coincides with the Annual General Meeting of the Friends of the Bodleian.

- ‹ previous

- 122 of 252

- next ›

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools  Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria

Tracking resistance: Mapping the spread of drug-resistant malaria Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?

Cities for cycling: what is needed beyond good will and cycle paths?