Jubilee Kings: Golden celebrations and appreciations

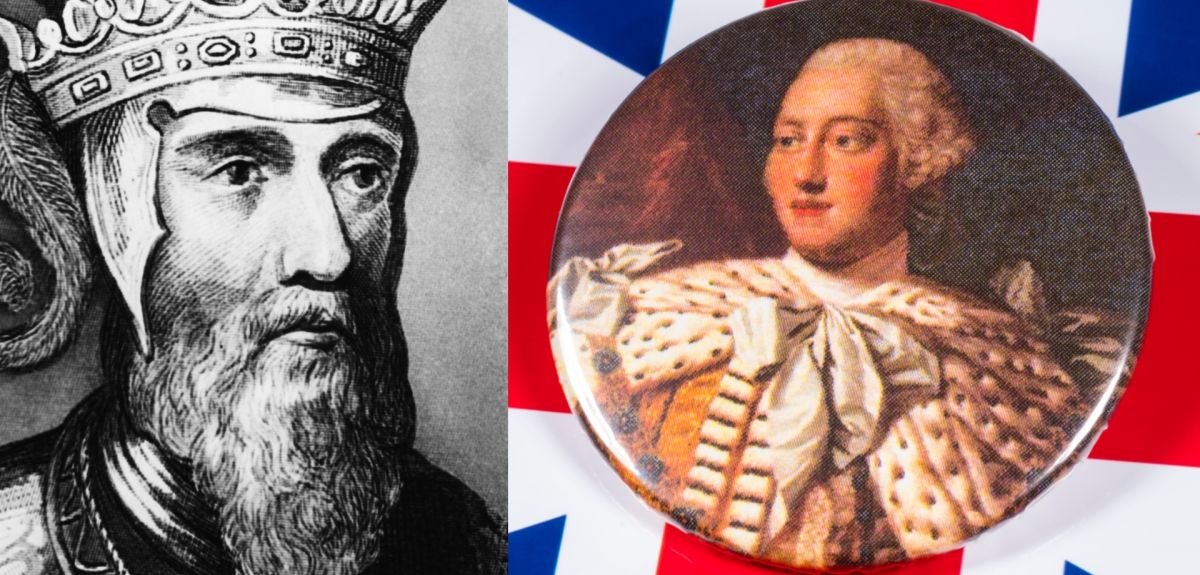

Her Majesty the Queen is the first British monarch to celebrate a Platinum Jubilee, but Royal Jubilees have been celebrated for hundreds of years – complete with military parades, porcelain memorabilia, special coins and much popular enthusiasm. The excitement and pageantry around Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee is well known and preserved in early film and photographs. But a Golden Jubilee was first celebrated by a British king, Edward III, in the 12th century, and Victoria’s grandfather, George III, was acclaimed some 200 years’ ago, for his 50 year reign – in spite of early unpopularity, growing radicalism and debilitating mental illness.

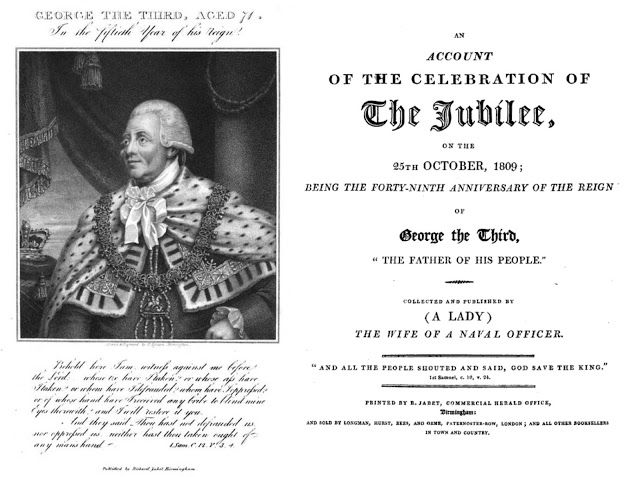

George III. Reign 1760-1820

George III is best known for this long illness and for ‘losing’ the American colonies. But the pattern and many of the traditions around the monarchy and in terms of royal jubilees began in his reign and the monarch came to be seen popularly as synonymous with Britain.

George III: Royal Jubilee

George III: Royal Jubilee Despite this, however, the Hanoverian king eventually came to be associated with patriotism and the essence of Britishness. This, perhaps, began with his person. Most scholars now would say he made poor choices initially, but not many doubt his sincerity and they recognise he took his duties very seriously. He was not a spendthrift and he was a devoted family man and the image started to change.

Edward III. Reign 1327-1377

On 28 January 1377, Adam Houghton, bishop of St David's, addressed the English parliament in the Painted Chamber at Westminster. He told the assembled lords and commons that Edward III had now occupied the English throne for over 50 years, and thus announced the end of Edward’s ‘jubilee year or year of grace’.

The English government had been determined to celebrate Edward’s jubilee year with a series of public spectacles. First, the king presided over a week-long tournament held at Smithfield in February 1376. Second, he played his part in a meeting of the Order of the Garter at Windsor Castle in April 1376. But thereafter the festivities fizzled out. A further tournament that had been planned to take place at Smithfield in June was cancelled. The remainder of Edward’s jubilee year was dominated by the political fallout from the explosive ‘Good Parliament’, which lasted from April to July; the sorrow which met the death of the king’s first-born son – the Black Prince – on 8 June; and the king’s own failing health.

Nonetheless, there were some muted celebrations to mark the day of Edward’s jubilee itself, which fell on 25 January 1377. According to the Anonimalle Chronicle, ‘the commons of London made great entertainment and celebration’, culminating in a show before the Prince of Wales and other members of the nobility in Kennington. However, there are no signs that either the royal court or other towns and cities did much to mark the occasion. Indeed, one man was conspicuously absent from both the celebrations in London and the parliament which opened two days later: the king himself. Edward III was confined to his quarters at his manor of Havering in Essex, and was too unwell to travel; as Houghton explained, he had been laid low and ‘in great peril of his life’. When he finally left Havering the following month, to move to his manor of Sheen in Surrey, a chronicler reported that he made the journey with ‘great frailty’. While the cause of Edward’s ill-health is unclear – although it is likely that he suffered from a series of debilitating strokes – he did not recover, and died on 21 June 1377, at the age of sixty-four.

Although Edward’s infirmity cast a shadow over the last years of his reign, it should not blind us to what he achieved during his fifty years on the throne. When Edward was crowned in 1327, the English monarchy had been in the midst of an unprecedented crisis. His father, Edward II, aroused discontent, distrust, and anger because of his regime’s harsh and heavy-handed treatment of political society; his government’s military failures against both France and Scotland; and his own scandalous relationship with his favourites, Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger. This led to Edward II being overthrown in the first deposition of an English king since the Norman Conquest. Yet over the course of his reign, Edward III rebuilt the monarchy’s prestige and reputation, restored the crown’s relationship with the aristocracy, and revived England’s military fortunes, with English forces triumphing over their French foes at the Battles of Crecy and Poitiers in 1346 and 1356 respectively.

The response to Edward’s death suggests that his subjects appreciated his accomplishments and longevity. The chronicler, Jean Froissart, remarked that his death was ‘to the deep distress of the whole realm of England, for he had been a good king for them’, and described how his funerary procession was observed by mourning crowds. Other commentators also heaped praise on the departed king; Thomas Walsingham, a monk of St Albans, later wrote that ‘among all the world’s kings and princes, he [Edward] had been a glorious king, benevolent, merciful, and magnificent’. But perhaps the most remarkable tribute to the king is the inscription that runs around the perimeter of his tomb:

‘Here is the glory of the English, the paragon of past kings,

The model of future kings, a merciful king, the peace of the peoples,

Edward the Third, fulfilling the jubilee of his reign.

The unconquered leopard, he was a powerful Maccabeus in his wars.

While he lived prosperously, he restored to life his kingdom in probity.

He ruled mightily in arms; now in heaven may he be heavenly king’.

By Sam Lane

The mental illness which affected him was partly responsible for George III’s rehabilitation. He was seen sympathetically as a ‘King Lear-like figure’. And, in a defining 1984 article about George III , Princeton Professor Linda Colley says, ‘After 1789, prints portrayed him regularly as St. George, as John Bull and, after his mental collapse in 1810, as a wise, Lear-like patriarch and the celestial guardian of his nation.’

As well as increasing personal sympathy for ‘Farmer George’, the monarchy became the symbol of Britishness to counter the forces of autocracy that were seen on the Continent.

A mark of the considerable change in mood during his reign, was the reaction to his death in 1820. Some 30,000 people gathered for the funeral, although he had been unwell for the last decade, it was described as ‘if the paternal roof had fallen in, and left our chambers desolate’. Shops across England, Scotland and Wales closed.

Although such marks of respect might be expected now, that had not been the case in the early part of George III’s reign – or in respect of his immediate predecessors. Since Charles II, the monarchy had not enjoyed unalloyed popularity, especially with radical politics gaining ground.

Although such marks of respect might be expected now, that had not been the case in the early part of George III’s reign – or in respect of his immediate predecessors. Since Charles II, the monarchy had not enjoyed unalloyed popularity, especially with radical politics gaining ground.

According to Professor Colley’s article, ‘Ever since the passing of that immediate euphoria which greeted the Restoration, no English or British monarch other than perhaps Anne had achieved more than partial or transient popularity; no sovereign at all had been able to act as an unquestioned cynosure for national sentiment.’

So much had changed, though, that when George celebrated the beginning of his 50th year of kingship on 25 October 1809 – the first Golden Jubilee in 500 years. Lord Palmerston said, ‘Nothing could be better than its effect in London.'

In the course of George III’s reign, the view of the monarchy had changed. The main national anthem became ‘God save the King’, supplanting Rule Britannia. The State Coach was built, which was used at Her Majesty the Queen’s Coronation and will feature in this year's Platinum Jubilee procession. And a new focus on the monarch was used to distinguish patriotic British celebrations from those in revolutionary France.

Not all were convinced, as Professor Colley pointed out, Sir Francis Burdett claimed in the House of Commons that George Ill's jubilee was a "clumsy trick, to thrust joy down the throats of the people", in the wake of soaring food prices and other misfortunes[1].

But celebrations took place around the country and these were not always organised officially, with Napoleon in mind. Local authorities and individuals organised and led events nationally. And the Press was key in encouraging support, although what would today be called liberal elites criticised the celebrations.

According to Professor Colley, however, ‘The sheer scale of this event was a remarkable tribute to the activism of the press and, it would seem to public opinion which compelled many local authorities into action.’

According to Professor Colley, however, ‘The sheer scale of this event was a remarkable tribute to the activism of the press and, it would seem to public opinion which compelled many local authorities into action.’

At the same time, some of the other familiar activities around royal events developed - a thriving souvenir trade was established, Jubilee good works were encouraged, great crowds gathered to celebrate and sermons were preached.

During his reign, George III gradually became more popular in his own right. But the French Revolution, and the execution of the French monarch, would serve to cement his position as the father of the nation. These firmly established the British monarchy as the rallying point for patriotism - in contrast to the Revolutionary events in France and Napoleon’s 'adventures' across the Continent.

There were very real invasion scares in the early 1800s and the traditional Anglo-French rivalry came to be seen differently. By the time of his Golden Jubilee in 1809, the safety of the state was associated with the safety of the King.

With thanks to Dr Perry Gauci

[1] Professor Linda Colley: The Apotheosis of George III: Loyalty, Royalty and the British Nation 1760-1820. Pages 94-129 Past & Present, volume 102, Issue 1, February 1984.

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations

25-year Oxford study finds the effects of conflict last for generations What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators