Hearing through the overwhelming silence: enslaved ancestors found in Bodleian archives by opera star

Acclaimed baritone Peter Brathwaite was in conversation at the Bodleian libraries this week, as part of its new racial equality event series We Are Our History Conversations. His talk, on the theme of ‘Black Lives in the Archives’, was inspired by his mission to uncover the forgotten and unheard voices of black and enslaved people from history, including those of his own ancestors.

In conversation with Professor Farah Karim-Cooper, Professor of Shakespeare Studies at King’s College, London, the opera star talked about his journey through the Bodleian’s archives to discover his own enslaved ancestors on Barbados – and hear their voices in between the lines of letters which mentioned them just in passing.

Peter Brathwaite

Peter Brathwaite

He began the project during the pandemic – as he personally reinterpreted dozens of pictures, including one of him as President Obama, as well as him as ancient kings, queens, saints, servants, slaves and even as a Black Madonna. It is both a playful and deeply insightful series. He says, ‘I recreated one every day for 50 days…Black sitters were often unknown or not yet known, as I prefer to say. They needed filling out, a narrative to be constructed and that’s what I was trying to do.’

Peter personally reinterpreted dozens of pictures, including one of him as President Obama, as well as him as ancient kings, queens, saints, servants, slaves and even as a Black Madonna....He says, ‘...Black sitters were often unknown or not yet known, as I prefer to say. They needed filling out...and that’s what I was trying to do

Mr Brathwaite continues, ‘I wanted to hear what they were saying. They had been imagined through the white gaze and I wanted to look at them through the eyes of the sitter.’

It is this approach which has seen the singer engage in months of passionate scholarship in Barbados and in the UK, looking for traces of his ancestors in archives not written from their perspective or even with them in mind.

‘I always had this urge to dig. I wanted to shift the perspective and so I read around the subject extensively,’ he explains. ‘I wanted to learn more about these real people from history.’

His research has proved very successful, although extremely difficult at times, as he uncovered the lives of his enslaved ancestors and learnt more about his forebears.

‘I am descended from white enslaving plantation owners [from whom the name Brathwaite comes] and from enslaved black people…it’s messy, but we think my four times great grandfather, Addo Brathwaite, came from Ghana.’

I am descended from white enslaving plantation owners [from whom the name Brathwaite comes] and from enslaved black people…my four times great grandfather, Addo Brathwaite, came from Ghana

Peter Brathwaite

Clearly passionate to know more, he tells the story of how he found this ancestor named in letters in the Bodleian – revealing a tantalizing glimpse of what may possibly still be uncovered.

Addo had been brought to the West Indies to be a field slave, he became a house slave, and eventually was a free person of colour. Through his research, Peter has found, Addo and his wife Margaret, who was of mixed race, worshipped at the local black church – a fact noted in the Bodleian letters. When he came upon the letters, he was stunned to discover they mentioned his ancestors by name and revealed the couple were seen by the author as respectable examples for the enslaved people of the island.

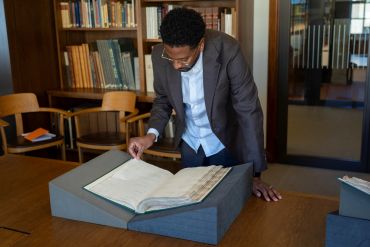

Peter Brathwaite at the Bodleian

Peter Brathwaite at the Bodleian

But, says Peter, by reading against the grain, he tried to find the real Addo and Margaret and the submerged West African culture from which Addo had been taken.

‘Going to church was not just an expression of their faith, but also of the new society in which they lived. But there are hints of the culture: the fact that in Ghanian tradition, women are keepers of generational knowledge and Margaret established the tradition of having a family festival on 2 July each year – which is still going and is similar to the Yam festivals in West Africa. And they established a family village in Barbados, for their extended family.’

There are hints of the submerged culture: the fact that in Ghanian tradition...they established a family village in Barbados, for their extended family

Peter Brathwaite

Also, he says, for the festival, Margaret asked for the hymn ‘Hark, my soul! It is the Lord,’ which was written by a well-known abolitionist.

Peter discovered Margaret had been freed by her own half-brother, John. Their father was one of the infamous Brathwaite’s, who Peter says, it has been hard to avoid in his research. The young John had attended Christ Church – and Peter wonders if he ever brought Margaret to Oxford with him, as did happen with favourite slaves.

‘It’s pain-staking work,’ Peter says earnestly. ‘But you can find little nuggets. It’s really important for people to hear this. If you move away from the data, you can find the people behind the numbers.’

It’s pain-staking work...But you can find little nuggets. It’s really important for people to hear this. If you move away from the data, you can find the people behind the numbers

Peter Brathwaite

When he stumbled on the names of his own ancestors, Peter had been stunned, ‘To turn the pages and absorb - the effect was incredible. It was an encounter with the archives.’

But, he warns, it was something that needs to be done with care because of the ‘visceral violence’ and challenging terminology of the historic papers. He says, ‘It is not easy.’

Jasdeep Singh, Project Manager for the Bodleian’s We Are Our History initiative, explains how the libraries are working to reveal hidden stories in the archives and make them more publicly accessible, with the project, ‘We’re taking a fresh look at imbalances in the collections. From digitization to exhibitions, we’re looking at the impact of the colonial era in the libraries.’

Royal Opera House, 'Insurrection A Work in Progress' by Peter Brathwaite. Highlighting Barbadian folk traditions as a form of resistance.

Photo Credit: Sama Kai

Most of the colonial papers dominated by the voice of officials, researchers in this area are often left with fragments of history that detail the silenced voice...But sometimes, those fragments are brought together by people like Peter. When these surface, they make really powerful stories

Jasdeep Singh, Bodleian libraries

Peter concludes, ‘Not everyone can find their family history. You feel in the dark and grasp at little clues. So much is lost. There is an overwhelming silence. It is deafening.’

The Bodleian's We Are Our History project was inspired by the famous James Baldwin quote: 'History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history....'

For further information about the We Are Our History work, and conversations series visit the project website here: We Are Our History | Bodleian Libraries (ox.ac.uk)

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools