Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Brian Christian is an acclaimed American author and researcher who explores the human and societal implications of computer science. His bestselling books include ‘The Most Human Human’ (2011), ‘Algorithms to Live By’ (2016), and ‘The Alignment Problem’ (2021), the latter of which The New York Times said ‘If you’re going to read one book on artificial intelligence, this is the one.’ He holds a degree from Brown University in computer science and philosophy and an MFA in poetry from the University of Washington.

Here, Brian talks about the latest chapter of his career journey: starting a DPhil (PhD) at the University of Oxford to grapple with the challenge of designing AI programs that truly align with human values.

Brian at the entrance of Lincoln College, Oxford. Credit: Rose Linke.

Brian at the entrance of Lincoln College, Oxford. Credit: Rose Linke.

One of the fun things about being an author is that you get to have an existential crisis every time you finish a book. When The Alignment Problem was published in 2021, I found myself ‘unemployed’ again, wondering what my next project would be. But writing The Alignment Problem had left me with a sense of unfinished business. As with all my books, the process of researching it had been driven by a curiosity that doesn’t stop when it reaches the frontiers of knowledge: what began as scholarly and journalistic questions simply turned into research questions. I wanted be able to go deeper into some of those questions than a lay reader would necessarily be interested in.

The Alignment Problem is widely said to be one of the best books about artificial intelligence. How would you summarise the central idea of the book?

The alignment problem is essentially about how we get machines to behave in accordance with human norms and human values. We are moving from traditional software, where behaviour is manually and explicitly specified, to machine learning systems that essentially learn by examples. How can we be sure that they are learning the right things from the right examples, and that they will go on to actually behave in the way that we want and expect?

This is a problem which is getting increasingly urgent, as not only are these models becoming more and more capable, but they are also being more and more widely deployed throughout many different levels of society. The book charts the history of the field, explains its core ideas, and traces its many open problems through personal stories of about a hundred individual researchers.

Most AI systems are built on the assumption that humans are essentially rational but we all act on impulse and emotionally at times. However, there is currently no real way of accounting for this in the algorithms underpinning AI.

So, how does this relate to your DPhil project?

Under the supervision of Professor Chris Summerfield in the Human Information Processing lab (part of the Department of Experimental Psychology), I am exploring how cognitive science and computational neuroscience can help us to develop mathematical models that capture what humans actually value and care about. Ultimately, these could help enable AI systems that are more aligned with humans – and which could even give us a deeper understanding of ourselves.

For instance, most AI systems are built on the assumption that humans are essentially rational utility maximisers. But we know this isn’t the case, as demonstrated by, for instance, compulsive and addictive behaviours. We all act on impulse and emotionally at times - that’s why they put chocolate bars by the checkouts in supermarkets! But there is currently no real way of accounting for this in the algorithms underpinning AI.

To me, this feels as though the computer sciences community wrote a giant IOU: ‘insert actual model of human decision making here.’ There is a deep philosophical tension between this outrageous simplification of human values and decision making, and their use in systems that are becoming increasingly powerful and pervasive in our societies.

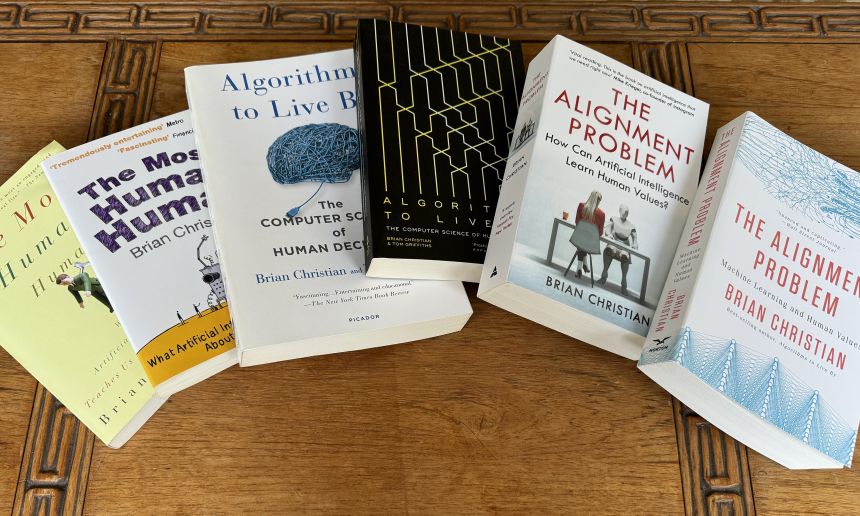

US and UK editions of Brian Christian’s three books on artificial intelligence. Credit: Brian Christian.

US and UK editions of Brian Christian’s three books on artificial intelligence. Credit: Brian Christian.And how will you investigate this?

I am currently developing a roadmap with Chris and my co-supervisor Associate Professor Jakob Foerster (Department of Engineering Science) that will involve both simulations and human studies. One fundamental assumption in the AI literature that we are probing is the concept of “reward.” Standard reinforcement-learning models assume that things in the world simply have reward value, and that humans act in order to obtain those rewards. But we know that the human experience is characterized, at a very fundamental level, by assigning value to things.

There’s a famous fable from Aesop of a fox who, failing to jump high enough to reach some grapes, declares them to have been “sour” anyway. The fox, in other words, has changed their value. This story, which has been passed down through human culture for more than two millennia, speaks to something deeply human, and it offers us a clue that the standard model of reward isn’t correct.

This opens up some intriguing questions. For instance, what is the interaction between our voluntary adoption of a goal, and our involuntary sense of what the reward of achieving that goal will be? How do humans revise the value, not only of their goal itself but of the other alternatives, to facilitate the plan they have decided to pursue? This is one example of using the tools of psychology and computational neuroscience to challenge some of the longstanding mathematical assumptions about human behaviour that exist in the AI literature.

We are moving from traditional software, where behaviour is explicitly specified, to machine learning systems that essentially learn by examples. How can we be sure that they are learning the right things from the right examples, and that they will go on to actually behave in the way that we want?

Does the future of AI frighten you?

Over the years I have been frightened to different extents by different aspects of AI: safety, ethics, economic impact. Part of me is concerned that AI might systematically empower people, but in the wrong way, which can be a form of harm. Even if we make AI more aligned, it may only be aligned asymmetrically, to one part of the self. For instance, American TikTok users alone spend roughly 5 billion minutes on TikTok a day: this is equivalent to almost two hundred waking human lifetimes. A day! We have empowered, at societal scale, the impulsive self to get what it wants – a constant stream of diverting content – but there is more to a life well lived than that.

Do you feel academia has an important role in shaping the future of AI?

Definitely. What is striking to me is how academia kickstarted a lot of the current ideas behind AI safety and AI alignment – these started off on the whiteboards of academic institutions like Oxford, UC Berkeley, and Stanford. Over the last four years, those ideas have been taken up by industry, and AI alignment has gone from being a theoretical to an applied discipline. I think it is very important to have a heterogenous and diverse set of incentives, timescales, and institutional structures to pursue something as big, critical. and multidimensional as AI alignment.

Academia can also have more longevity than industrial research labs, which are typically at the mercy of profit motivations. Academia isn’t so tied to boom and bust cycles of funding. It might not be able to raise billions of dollars overnight, but it isn’t going to go away with the stroke of a pen or a shareholder meeting.

Oxford's unique college system really fosters a sense of community and intellectual exchange that I find incredibly enriching. It is inspiring, it gives you new ideas, and provides a constant reminder of how many open frontiers there are, how many important and urgent open problems.

Why did you choose Oxford for your PhD?

I came to Oxford many times to interview researchers while working on The Alignment Problem. At the time, the fields of AI ethics, AI safety, and AI policy were just being born, with a lot of the key ideas germinating in Oxford. I soon became enamoured of Oxford as a university, a town, and an intellectual community - I felt a sense of belonging and connection. So, Oxford was the obvious choice for where I wanted to do a PhD, and I didn’t actually apply to anywhere else! What sealed it was finding Chris Summerfield. He has a really unique profile as an academic computational neuroscientist who has worked at one of the largest AI research labs, Google DeepMind, and now at the UK’s AI Safety Institute. We met for coffee in 2022 and it all went from there.

What else do you like about being a student again?

Oxford's unique college system really fosters a sense of community and intellectual exchange that I find incredibly enriching. In the US, building a community outside your particular discipline is not really part of the graduate student experience, so I have really savoured this. It is inspiring, it gives you new ideas, and provides a constant reminder of how many open frontiers there are, how many important and urgent open problems. When you work in AI, there can be a tendency sometimes to think that it is the only critical thing to be working on, but this is obviously so far from the truth.

Outside of my work life, I play the drums, and a medium-term project is to find a band to play in. Amongst many other things, Oxford really punches above its weight on the music scene, so I am looking forward to getting more involved in that. Once the weather improves, I also hope to take up one of my favourite pastimes – going on long walks – to explore the wealth of surrounding landscape. As someone who spends a lot of time sitting in front of computers while thinking about computers, it is immensely refreshing to get away from the world of screens and step into nature.

A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future

A blueprint for sustainability: Building new circular battery economies to power the future Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance

Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women How artificial intelligence is shaping medical imaging

How artificial intelligence is shaping medical imaging