Expert Comment: The world’s most important antibiotic has become our greatest challenge

Today, on the 80-year anniversary of the Nobel Prize being awarded for the discovery and development of penicillin, Dr Alistair Farley, Scientific Lead at the Ineos Oxford Institute for antimicrobial research (IOI), urges that the collaboration behind this achievement is channelled again today to address one of the greatest global medical challenges of our time.

Dr Alistair Farley. Credit: The IOI.

Dr Alistair Farley. Credit: The IOI.The development of penicillin established a new model for translational research. Fleming’s discovery of penicillin from the Penicilium mould was published as a curious observation. Building on these findings, Florey, Chain and Norman Heatley at the Dunn School of Pathology in Oxford isolated penicillin for the first time, with bedpans being used to grow and ferment the mould. Although quantities of pure penicillin were limited, they were sufficient to demonstrate its curative effects in mice and a human patient. The penicillin program was subsequently supported by a grant by the Rockefeller foundation, then by involvement of British and US pharmaceutical companies, backed by their governments. This led remarkably quickly to mass production of penicillin, in an early example of transatlantic collaboration for biomedical research.

The golden age of antibiotics and the rise of resistance

The development of penicillin heralded an era of incredibly productive antibiotic discovery and medical advancements. Infections like gonorrhoea and pneumonia that used to be fatal or severely debilitating were now treatable, and antibiotic-enabled breakthroughs occurred across diverse medical fields such as surgery, trauma medicine, and cancer care. The majority of antibiotic classes in use today were identified between approximately 1940 to 1965 in the golden age of antibiotics.

The development of penicillin heralded an era of incredibly productive antibiotic discovery and medical advancements. Infections that used to be fatal or severely debilitating were now treatable, and antibiotic-enabled breakthroughs occurred across diverse medical fields.

Bacteria, like all living organisms, evolve and adapt to selection pressures, and there were increasing reports of resistance to antibiotics during this time (now known as antimicrobial resistance, AMR). Indeed, in Fleming’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech, he warned of the dangers of using sub-lethal amounts of penicillin as this would lead to bacteria that are resistant to penicillin. Bacteria can adapt by, for instance, preventing the drugs entering cells, or by pumping drugs out of cells using efflux pumps. The target of the antibiotic in the bacteria can also be modified, reducing the efficacy of the drug, or the bacteria can produce degrading enzymes such as β-lactamases which destroy the antibiotic before it reaches its target.

Many factors promote AMR, including antibiotics being cheap and commonly overprescribed, treatment courses being finished early, lack of basic hygiene and sanitation in many low- and middle-income countries, and antibiotics being used as growth promoters in livestock production.

Today, AMR is forecast to cause 39 million deaths by 2050 if unaddressed, contributing to a GDP loss of $1-3.4 trillion per year by 2030. We are, however, already witnessing the devastating impacts of AMR all around us. In 2023, one in 6 bacterial infections worldwide were resistant to antibiotics, and there were 4.71 million deaths associated with AMR in 2021. The burden of AMR disproportionately affects LMICs, babies in Nigeria are rapidly colonised with multi-drug resistant bacteria in their guts, and antibiotics are becoming increasingly ineffective in treating common illnesses such as urinary tract infections.

Finding the next generation of antibiotics

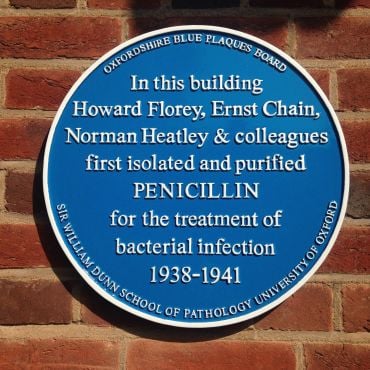

Blue plaque at the Dunn School of Pathology. Credit: Owen Massey McKnight.

Blue plaque at the Dunn School of Pathology. Credit: Owen Massey McKnight.Here at the IOI, we are developing new antibiotics and finding innovative ways to extend the lifetime of existing ones.

We collect bacterial samples from parts of the world where resistance is greatest, and analyse their genes and resistance mechanisms. These data inform our drug discovery pipeline, from target identification to candidate development. The samples allow us to test our antibiotics in development directly on contemporary drug-resistant isolates and to develop drugs that are effective in regions of the world with the highest rates of resistance.

We are:

- Designing new compounds, also known as inhibitors, that block resistance mechanisms in drug-resistant bacteria.

- Developing new combinations of existing antibiotics to increase their effectiveness.

- Designing and developing the next generation of penicillin antibiotics.

Our aim is to develop new antibiotics for infections and diseases such as bloodstream infections and complicated urinary tract infections, as well as tuberculosis, which are all becoming increasingly difficult to treat.

The next frontiers in combatting AMR

Most pharmaceutical companies are no longer actively researching and developing new antibiotics, in part due to market failures and low initial commercial returns.

Developing new antibiotics is vital, but cannot be the only solution to AMR. Resistance is largely a natural response to antibiotic use. Over time, even the newest and most effective antibiotics will lose their effectiveness unless we also change how we use and manage them.

Addressing this threat requires interdisciplinary and global effort. AMR affects all of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), disproportionately affecting underprivileged populations. We need better antibiotic stewardship, rapid, cost-effective, and reliable diagnostic tests, improved sanitation and (where appropriate) effective preventative vaccinations.

Over 200 researchers at the University of Oxford are tackling antimicrobial resistance from different, but interconnected approaches:

- A group of researchers at the Oxford Martin School are developing rapid tests that can both identify bacterial species and establish which antibiotics they are susceptible to, in as little as 30 minutes.

- Researchers at the Department of Engineering have developed a new drug delivery system using ultrasound-activated nanoparticles to destroy bacterial biofilms. This offers a promising solution to patients suffering from chronic antibiotic-resistant infections.

- The Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU) are supporting a project in Cambodia using circus arts to raise awareness about appropriate use of antibiotics in the community.

- A team of microbiologists at the IOI are working with healthcare professionals in 28 hospitals and clinics across 7 countries to improve the treatment of bloodstream infections, including sepsis.

Developing new antibiotics is vital, but cannot be the only solution to AMR… Over time, even the newest and most effective antibiotics will lose their effectiveness unless we also change how we use and manage them.

As we celebrate and reflect on the 80-year anniversary of the Nobel Prize being awarded for penicillin, we should channel the urgency and collaboration shown by the penicillin team, integrating new technologies available to us to tackle one of the most pressing issues facing human health.

The international synergy of universities, industry, philanthropy, and government was crucial to turn Fleming’s observation into a mass-produced breakthrough drug. We must continue global collaborative efforts and build on penicillin’s legacy. The cost of not doing so will lead us into a post-antibiotic era with profound consequences for us all.

For more information about this story or republishing this content, please contact [email protected]

The King presents The Queen Elizabeth Prizes for Education

The King presents The Queen Elizabeth Prizes for Education

Social Sciences Impact Conference to bring together researchers and partners to explore ‘Impact in Motion’

Social Sciences Impact Conference to bring together researchers and partners to explore ‘Impact in Motion’

Expert Comment: Could oil price surge accelerate the UK’s shift to renewables?

Expert Comment: Could oil price surge accelerate the UK’s shift to renewables?

Professor Rebecca Eynon elected to prestigious Academy of Social Sciences Fellowship

Professor Rebecca Eynon elected to prestigious Academy of Social Sciences Fellowship

First volunteer receives Lassa Fever vaccine in cutting-edge Oxford trial

First volunteer receives Lassa Fever vaccine in cutting-edge Oxford trial

Rapid, low-cost tests can help prevent child deaths from contaminated medicinal syrups

Rapid, low-cost tests can help prevent child deaths from contaminated medicinal syrups

New study warns of 'creeping catastrophe' as climate change drives a global rise in infectious diseases

New study warns of 'creeping catastrophe' as climate change drives a global rise in infectious diseases