Features

Imagine saving a million lives. While the world was in the first throes of the pandemic and paralysed in the face of the seemingly unstoppable spread of the coronavirus, two Oxford professors, Peter Horby and Martin Landray, started a trial which is estimated to have saved around one million lives with a £5 medicine that is available across the world.

In an interview for Science blog, Professor Landray explains that he mooted the idea on 28 Feburary 2020, in an email to Sir Jeremy Farrar, the head of Wellcome. A few days later, they discussed it on a No 18 bus to Marylebone. Sir Jeremy suggested he join forces with Professor Horby, an expert in infectious diseases and epidemiology and a nodding acquaintance from Oxford’s medical science community. And the rest really is history.

In an interview for Science blog, Professor Landray explains that he mooted the idea on 28 Feburary 2020, in an email to Sir Jeremy Farrar, the head of Wellcome. A few days later, they discussed it on a No 18 bus to Marylebone. Sir Jeremy suggested he join forces with Professor Horby, an expert in infectious diseases and epidemiology and a nodding acquaintance from Oxford’s medical science community. And the rest really is history.

Treatments for COVID-19 were urgently needed in early 2020, since there were no known treatments when the virus took hold. Oxford colleagues had quickly begun working on a vaccine, but Professor Landray, an expert in heart conditions and drugs trials, suggested that a trial be conducted with hospitalised patients to see if any existing medicines could be used in the fight against the worst effects of the virus. Speed was of the essence; treatments were needed rapidly whilst vaccines were being developed and rolled out – and they are still a crucial piece of the jigsaw needed to complement preventative measures and save lives.

Within days, with backing from Oxford colleagues, they had set up and gained approval for the ground-breaking RECOVERY trial. By 19 March, they had recruited their first participant. Three months later, they had found the first proven effective treatment.

Simplicity was the key, according to Professor Landray, ‘Patients were very sick and we couldn’t burden the NHS with demands on their time....a streamlined clinical trial which was integrated with clinical care was the only way.’

Within days...the pair had set up and gained approval for the ground-breaking RECOVERY trial. By 19 March, they had recruited their first participant. Three months later, they had found the first proven effective treatment.

So, clinicians were asked to enter basic patient details on the trial website and, initially, the system randomly allocated one of four carefully-chosen drugs, each offering the potential to tackle the disease, or no additional treatment alongside oxygen and ventilator treatments. It was a classic randomised controlled trial – including a control sample who received no additional treatment beyond the usual care in their hospital – but one which had not been used in such circumstances before.

The medical profession in the UK responded with alacrity and enthusiasm, eager to help beat the virus. More than 4,000 medical professionals in every acute NHS hospital in the country took part and nearly 40,000 patients have now been enlisted.

‘Many clinicians grabbed the opportunity to help find solutions to this crisis,’ says Professor Landray. ‘And we couldn’t have done it without their support.’

A triumph for collaboration and research, by mid-June, dexamethasone, a commonly-available steroid, was found to be effective in patients on ventilators and those receiving oxygen. ‘It had very clear benefits,’ says Professor Landray, remembering the excitement around the finding. ‘We’d never seen anything like it.’

Many clinicians grabbed the opportunity to help find solutions to this crisis...and we couldn’t have done it without their support

Professor Martin Landray

It was not a cure, but it prevented 30% of deaths and it quickly became standard care around the world – reversing previous thinking which had suggested that it shouldn’t be used because it was ineffective or might even be harmful. In early June, another drug, hydroxychloroquine, which had been hailed as a miracle cure, was found by the trial to be useless for hospitalised patients.

They announced the dexamethasone news at 1pm on 16 June 2020, says Professor Landray. He was still talking to the media at 11pm. Professor Horby travelled to No10 to present the news alongside the Prime Minister at a Government briefing.

‘He was wearing my tie as didn’t have one with him,’ laughs Professor Landray, who takes no chances. ‘I had brought in two.’

A triumph for collaboration and research, by mid-June, dexamethasone, a commonly-available steroid, was found to be effective in patients on ventilators and those receiving oxygen

As the Deputy Director of Oxford University’s Big Data Institute, Professor Landray knows about large numbers. He is delighted by the success of the trial, especially the key role played by doctors, nurses, and patients in hospitals from the Western Isles to Truro, but he says, ‘What matters is that in 100 days, with all the people involved in the trial, a treatment was found.’

It has been a stunning success, and the professors were last week honoured to be elected as fellows of the Academy of Medical Sciences, alongside a host of Oxford colleagues, for their exceptional contributions to the advancement of medical science, an accolade that recognises the impact of RECOVERY and the importance of their previous work.

The building which houses Oxford’s Big Data Institute and part of the Nuffield Department of Population Health exemplifies Professor Landray’s streamlined approach, which is not surprising, since he was involved in the design - very modern, with clean, geometric lines, light wood panels and open offices. In usual times, it is alive with 500 data scientists, ethicists, philosophers, and population health experts, all under one beautiful roof.

Professor Landray credits the strength of the medical community at Oxford for much of his success. ‘We are very fortunate in Oxford. There is huge strength and depth. There are the people at Oxford who have written landmark papers, the headline people from conferences. I am very lucky to have had people to help, support and mentor me.’ He adds, ‘Richard Doll (the man credited with proving that smoking causes lung cancer) was here when I first moved to Oxford.’

There are the people at Oxford who have written landmark papers, the headline people from conferences. I am very lucky to have had people to help, support and mentor me

Professor Landray credits the strength of the medical community at Oxford

Professor Landray is an Oxfordshire local, who grew up and still lives in a village some half an hour’s drive from the city. He literally married the girl next door – although to be precise, of course, he says, ‘She lived about 50 yards away.’

Professor Landray knew early on that he wanted to be a doctor. ‘Medicine was all around us, my mother was a part-time anaesthetist, my father was the local GP – very much in the James Herriot style.’

Some of his earliest memories are of patients coming to the house and lying on the family sofa, so his father could examine them.

‘I never thought about doing anything else,’ says Professor Landray. Life as a local GP was not to be, though, since after medical school at Birmingham University, the young doctor never did take over from his father, becoming instead a clinical pharmacologist and heart specialist.

In fact, until the pandemic, he had not taken much of an interest in infections since 1980, when the young Martin wrote an article about germs for the local children’s newspaper. Clearly amused, he says, ‘It’s in the Bodleian, complete with a picture of a germ I drew myself. I didn’t publish another paper on infections until 2020.'

Professor Peter Horby (tieless) and Professor Martin Landray were last week honoured to be elected as fellows of the Academy of Medical Sciences.

Photo by John Cairns.

Professor Peter Horby (tieless) and Professor Martin Landray were last week honoured to be elected as fellows of the Academy of Medical Sciences.

Photo by John Cairns.He joined the group led by Professor Sir Rory Collins and Professor Sir Richard Peto, whose work on clinical trials for heart attack he had admired as a student.

‘I remember reading the results of their trial of aspirin and clot buster drugs for patients suffering a heart attack,’ he says of the Second International Study of Infarct Survival (known as ISIS-2). ‘It changed the treatment of heart attacks overnight.

‘It was so simple, so elegant, and so powerful.’

It made a massive impression on the young medic. Professor Landray’s enthusiasm is palpable as he talks about the potential for other trials in other diseases, building on the success of the RECOVERY trial.

RECOVERY has shown that, by combining scientific rigour with large numbers of participants and streamlined processes that make it easy for clinicians and patients to participate, it is possible to find which drugs work best rapidly, even in the context of a pandemic. According to Professor Landray, the potential of these kind of trials could be enormous for the fight against disease, but it runs counter to the ways trials are currently conducted.

‘Trials often cost $1 billion,’ he explains. ‘It’s a massive investment....even for big pharma, it’s a big cost. [Unlike RECOVERY] many trials are too small, too short, and too complex.’

Trials often cost $1 billion. It’s a massive investment....even for big pharma, it’s a big cost.. many trials are too small, too short, and too complex...RECOVERY has changed all that....So many areas need better treatments, we need to work out what works...It has to be the future

Professor Landray

And, because of that, a lot of areas of medicine rely on the opinions of doctors, who sometimes prescribe treatments based on ‘educated guess work’, rather than the hard data provided by a RECOVERY-style trial.

Assessing treatments as part of a randomised controlled trial enabled the team to see which yielded positive results – and which did not. In some situations, doctors do not have access to such information. Professor Landray says, ‘There is a real risk in throwing drugs at people if we don’t know if they’re going to work.’

He hopes, ‘RECOVERY has changed all that....So many areas need better treatments, we need to work out what works...It has to be the future. It’s possible to do much better on a much larger scale,’ he says. ‘You need scale for the data.’

Research may occupy him, but Professor Landray is every inch the sort of reassuring doctor you would want to see if unwell. Treating patients is important to the professor, who spends a morning in clinic each week, seeing members of the public.

‘Everything starts and finishes with patients,’ he says.

For more of the story, listen to: Inside Health, Recovery Trial, BBC Radio 4.

Some people are so energetic, dynamic and enthusiastic, they make you feel as though you do nothing but watch box sets while eating ice cream. But Nathalie Seddon’s passion for protecting nature and addressing climate change, makes you want drop the remote and follow her into the rainforest or the corridors of power, wherever she is going next. And you would not be alone.

Some people are so energetic, dynamic and enthusiastic, they make you feel as though you do nothing but watch box sets while eating ice cream. But Nathalie Seddon makes you want drop the remote and follow her

Oxford’s Professor of Biodiversity, from the university's Zoology department and Wadham college, is rightly something of a celebrity in the eco world. She is an official ‘friend’ of the COP26 climate conference. She has the ear of leading politicians and policymakers and she has been a determined force in the move to give ‘nature’ a place at the climate change top table.

Such concerns, plus expertise and leadership in climate and biodiversity has brought together key scientists and researchers, including Professor Seddon, from across Oxford's different departments and disciplines to deliver cutting-edge research, information and policy advice. The team includes Zoology, the Environmental Change Institute and the Smith School and initiatives such as Oxford Net Zero, the Oxford Martin School Programme for Biodiversity and Society and the Nature-based Solutions Initiative (Ever busy, Professor Seddon is a co-PI of the first two and directs the last).

But, in 2017, when Professor Seddon established the Nature Based Solutions Initiative at Oxford, few were talking about how nature fitted into discussions about global warming.

‘As a term, nature-based solutions wasn’t really in the lexicon,’ she says. ‘Now, it’s gone mainstream, viral even; now everyone seems to be talking about them – not just the conservation organisations, but those working in development, health, local businesses, banks, international corporations and governments.’

As a term, nature-based solutions wasn’t really in the lexicon. Now, it’s gone mainstream, viral even; now everyone seems to be talking about them

Professor Nathalie Seddon

Indeed, enter the words ‘nature-based solutions for climate change’ into Google, and a million results seem to pop up. It is one of the main themes for the UK-hosted climate change meeting in Glasgow in November (COP26) and at the forefront of discussions around climate change. And Professor Seddon, the doyenne of NbS [as they are known] is one of only 30 ‘friends’ of COP26, of whom just a handful are scientists.

But, until recently, Professor Seddon’s career involved far more hard science than scientific lobbying – although it also demonstrated the sort of single-minded determination which is proving so useful in pushing nature up the climate agenda. Her supportive parents encouraged her passion for nature but were not academics. Instead it was her headmaster who suggested that nature-mad Nathalie apply to study Natural Sciences at Cambridge. She won a place – and, to underline his conviction, did not leave until she had completed a doctorate and a junior research fellowship.

During the next 15 years, she travelled the world to study the lives of unusual birds and their songs. But this was not birdwatching as we know it [don’t mention the word twitcher].Then, as now, enthusiasm was her watchword. In her first year, the young student found a piece of paper on a noticeboard, asking for a birdwatcher for an expedition to Peru. It was a life-changing moment for a girl who had been mapping bird territories in her back garden since her family moved to the country when she was eight.

The Peruvian rainforest, by Chris Abney, Unsplash.

The Peruvian rainforest, by Chris Abney, Unsplash.Determined to go, she removed the paper from the board and a few months later found herself on a quest to find the Long-Whiskered Owlet while hiding from Shining Path guerrillas near the Peruvian border with Colombia. It was, perhaps, not the best way to start a life of scientific investigation. But her adventures did not stop there. That trip marked the beginning of a long passion for tropical wilderness and a fascination for understanding its unparalleled diversity.

To undertake her doctorate on the social behaviour and conservation of a threatened species of bird, the Subdesert Mesite (see below right), Nathalie had to drive solo across Madagascar in an ancient ex-military Land Rover she had transported by boat from Southampton. It might have been better had it never arrived since she spent more time trying to repair it than collecting data. And she says, ‘It turned out to be very challenging to study Mesites, as they live in the dense undergrowth of prehistoric spiny forests.’

Credit: Shutterstock. The Subdesert Mesite.

Credit: Shutterstock. The Subdesert Mesite.She says, with considerable feeling, ‘I loved being in those places....I am hugely privileged to have had worked there and those experiences enrich my every day and inform so much of the work I do. '

'Back then I was motivated by wanting to understand tropical diversity; now I am motivated by wanting to save it for future generations.’

Baobabs in Madagascar - by Haja Arson, Unsplash.

Baobabs in Madagascar - by Haja Arson, Unsplash.I discovered that hardly any knowledge we have about ecosystems and biodiversity was influencing big decisions that affect our futures...I found I could add value as a scientist to the policy environment...having children made me want to focus on the existential challenge that is climate change – and the intergenerational injustice we are perpetuating with our desecration of the natural world.

But what are NbS?

‘They are actions that involve working with nature for societal good,’ she says.

They involve community-led restoration and protection of mangroves, kelp forests, wetlands, grasslands and forests, bringing trees into working lands and nature into cities and much more.

It is now accepted that such actions can bring multiple benefits from storing carbon and protecting us from extreme events, to supporting biodiversity and providing jobs and livelihoods.

Critics sometimes argue that the potential contribution of nature to arresting climate change is tiny, compared with stopping fossil fuel use. But she insists, ‘Our work shows that nature has a role to play...and although new technology [to address climate change] might not be fully scalable until the end of the century, nature is here now, ready to be revitalised and can make a significant contribution to cooling this century.’

This is not mere dewy-eyed affection, although Professor Seddon clearly takes loss of biodiversity very personally.

‘Nature motivates, calms and grounds me,’ she says. But, she maintains, ‘We need nature because it is our life support system, because we are a part of it, not separate from it. There is huge value in the natural world, economically and ecologically, and huge risks of ignoring it...we have built our economies as if nature has no value; climate change and pandemics are showing us this not sustainable and that it is now time to repay our vast debt to nature.’

It is not just politicians, though, who have heard the call for nature – businesses too have made bold pledges. Everyone has heard about tree planting as an NbS. But this has not always been a positive move and some have planted trees to ‘offset’ their continued use of fossil fuels.

There is huge value in the natural world, economically and ecologically, and huge risks of ignoring it...we have built our economies as if nature has no value; climate change and pandemics are showing us this not sustainable and that it is now time to repay our vast debt to nature

Professor Seddon is concerned so-called ‘greenwashing is a really big issue’. She adds, ‘We need wood, and commercial planting can sometimes take the pressure off biodiverse native forests...also, in some parts of the world, where the land is badly degraded, tree plantations can help bring back soil health and are a step towards natural regeneration.’

But she warns, ‘Plantations are really bad news when they replace native habitats and violate human rights, and when they delay or distract from the urgent need to decarbonise.'

Professor Seddon is emphatic, 'Tree planting is not alternative to keeping fossil fuels in the ground...if we don’t, the resultant warming will undermine nature’s capacity to support us.'

She insists we cannot afford to ignore the harm we do to nature, ‘Covid shone a light on the risks of continued disrespect of the natural world. It also showed us that we cannot continue to travel and consume as much without paying severe consequences.’

But Professor Seddon has high hopes of the climate summit this year, where nature is a key theme.

‘For the UK,’ she says. ‘This is a real opportunity to show leadership. But to do that that, we need to get our own house in order and to shine light on good practice on nature-based solutions in our own country to inspire action globally.

‘We also need to end all the harmful subsidies that encourage land degradation and over-fishing and instead properly incentivise the careful stewardship of nature.’

We need to get our own house in order and shine light on good practice in our own country to inspire action globally...we also need to end all the harmful subsidies that encourage land degradation and over-fishing

Professor Seddon acknowledges the enormous role the great polluters need to play in reducing carbon emissions, but she sees considerable room for personal action, although it will mean substantial change for individuals, starting with moving, if possible, to a plant-based diet.

And, says the former globe-trotter, she could not quite bring herself to get on a plane again, unless there were a very good and urgent reason. And she says, ‘Scientists need to work with businesses and government to help them set realistic and robust evidence-based targets for climate and nature, and advise on how to reach those targets without compromising other goals for food security or economic recovery.’

Treading the corridors of power is a new path for Professor Seddon. But climate concerns have brought together scientists, looking for solutions, doing the hard-science to inform policy. She says, ‘There is a lot of really exciting fundamental research to be done to shore up the evidence around the value of working with nature in a warming world.’

She adds, ‘At Oxford, to address these knowledge gaps and meet policy needs, we’ve gone up a gear, we are working together more.’

And Professor Seddon is very much engaged in university life - delivering lectures, as Admissions Coordinator for Biology, interviewing candidates and working with young researchers and students. She says, 'Young people come asking what they should study to be part of it – to help. It’s our job to show them there is much they can learn and do, that they have real agency in their futures.'

At Oxford, to address these knowledge gaps and meet policy needs, we’ve gone up a gear, we are working together

She adds, ‘I am excited to be getting back into the science and to be working with colleagues from across the University and country to address fundamental questions about how we scale-up NbS...

'The next 10 to 20 years are going to be critical...Now is when the world needs us all to collaborate to enable transformational change.’

She concludes with hope for the future, ‘There is such a lot of good work going on around the world. Thousands of communities across the globe are implementing nature-based solutions to deal with climate change impacts, protect nature and support livelihoods. It is really inspiring. We all have a say in our futures...and as we work with nature we will heal ourselves.’

See latest research here. And a talk on NbS here: Evaluating and investing in Nature-based Solutions with Nathalie Seddon & Cameron Hepburn - YouTube

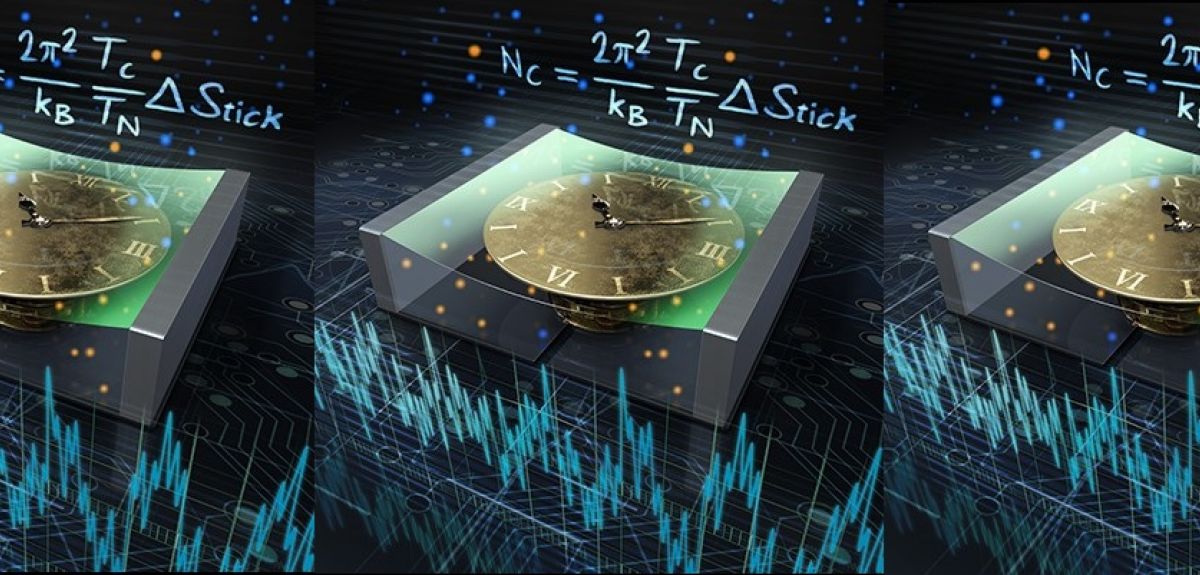

Clocks are essential building blocks of modern technology, from computers to GPS receivers. They are also essentially engines, irreversibly consuming resources in order to generate accurate ticks. But what resources have to be expended to achieve a desired accuracy? In our latest study, published in Physical Review X, we answer this question by measuring, for the first time, the entropy generated by a minimal clock.

Humans have mastered the art of timekeeping to an accuracy of approximately one second in every one hundred million years. However, the thermodynamic cost of timekeeping, i.e. its entropy production, has up to this point been unexplored.

Our experiment reveals that the hotter the clock, the more accurate the timekeeping, a prediction only expected to hold for quantum systems. Understanding the thermodynamic cost involved in timekeeping is a central step along the way in the development of future technologies, and understanding and testing thermodynamics as systems approach the quantum realm.

In a collaboration with Prof Marcus Huber at Atominstitut, TUWien, Dr Paul Erker and Dr Yelena Guryanova at the Institute for Quantum Optics and Quantum Information (IQOQI), and Dr Edward Laird at University of Lancaster, my colleagues, Dr Anna Pearson and Prof Andrew Briggs, and I designed a classical clock, with tuneable precision, to measure entropy production.

Our clock consists of a vibrating membrane integrated into an electronic circuit: each oscillation of the membrane provides one tick. The resources that drive the clock are the heat supplied to the membrane and the electrical work used to measure it. In operation, the clock converts these resources to waste heat, thus generating entropy. By measuring this entropy, we can therefore deduce the amount of resources consumed.

For the first time, we’ve shown a relation between the accuracy of a clock and its entropy production

By raising the energy, or “heat,” in the input signal, we were able to increase the amplitude of vibrations and in turn improve the precision of the membrane measurements. Our team found that the entropy cost - estimated by measuring the heat lost in the probe circuit - increased linearly with the precision, in agreement with quantum clock behaviour.

Our experiment reveals the thermodynamic costs of timekeeping. There is a relation between the accuracy of a clock and its entropy production; there is no such thing as a free minute - at least if you want to measure it.

For the first time, we’ve shown a relation between the accuracy of a clock and its entropy production, which although derived for open quantum systems, holds true in our nanoelectromechanical system.

Our results support the idea that entropy is not just a signature of the arrow of time... but a fundamental limit on clock's performance.

Our results support the idea that entropy is not just a signature of the arrow of time, or a prerequisite for measuring time’s passage, but a fundamental limit on clock's performance.

The relation between accuracy and entropy might be used to further our understanding of the nature of time, and related limitations in nanoscale engine efficiency.

Our device could allow us to investigate the particular trade-off predicted between clock accuracy, which as we showed is linked to available thermodynamic resources, and tick rate. This trade-off means that, for a given resource, a clock can have low accuracy and high tick rate or high accuracy but low tick rates.

Dr Natalia Ares is based at the Department of Materials.

Read the full paper 'Measuring the Thermodynamic Cost of Timekeeping' in Physical Review X.

By Ben Fernando

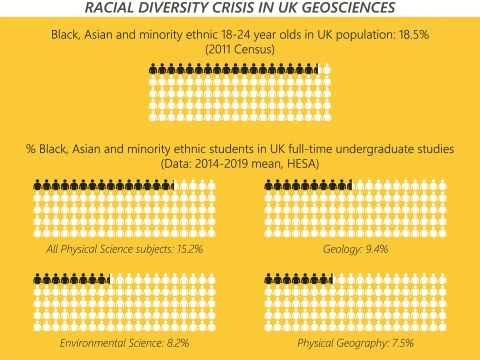

A recent article published in the journal Nature Geoscience has highlighted the shocking under-representation of students from ethnic minority backgrounds in the Geosciences.

The analysis indicates that Geology, Physical Geography and Environmental Science are the three worst Physical Science subjects for representation of Black, Asian and minority ethnic students in full-time undergraduate study in UK higher education, with poor progression into postgraduate research. In our paper, we lay out steps to address this diversity crisis and make the discipline more equitable.

In the 2018/19 academic year just 5.2% of Physical Geography postgraduates identified as Black, Asian, or minority ethnic, despite these groups comprising 18.5% of the UK 18-24 year old population. Over the past five years on average just 1.4% Geology postgraduate researchers identified as Black, compared to 3.8% of UK 18-24 year olds.

These data show that Geoscience subjects, which are crucial to developing the UK’s more sustainable future, have not adequately dealt with the legacy of the past when it comes to diversity and inclusion.

We hope that our work will galvanise the UK community into action and encourage other science disciplines to take similar steps.

Dr Natasha Dowey of Sheffield Hallam University, who led the analysis, commented: 'It’s about time these data are scrutinised. We see the lack of diversity every day in our university corridors. Our subjects are built on a legacy of imperialism and are impacted by structural barriers that discriminate against minority groups. It’s up to the entire geoscience community to make anti-racist changes and be positive allies to Black, Asian and minority ethnic students and colleagues.'

Professor Chris Jackson of the University of Manchester, a co-author on the piece and recently the first Black scientist to give a Royal Institution Christmas Lecture, said: 'Some people will only act against discrimination if they are presented with hard data. Here are those data, starkly outlining an issue that has been known for a long, long time. Those in power, who are invariably in the white majority, must now act.'

We recommend a range of interventions, including decolonisation work, ring-fenced opportunities for ethnic minority students, and meaningful reform of discriminatory recruitment and accreditation practices.

This analysis makes it undeniably clear that the geosciences in the UK has a serious diversity problem. Our hope is that by proposing concrete actions that institutions can take, this article will help form the basis for a solution.

Ben Fernando is a PhD student at the University of Oxford and campaigner for racial equality in STEM subjects.

Parents will worry, that is what parents do. But, according to Oxford Internet Institute researcher, Dr Matti Vuorre, the evidence base suggesting a negative impact of the use of technology on teenagers’ mental health is thin - at best.

Dr Vuorre and colleagues Dr Amy Orben and Professor Andy Przybylski have been studying the associations between technology use and adolescent mental health – and, according to new research, it is not all bad news, not at all.

It is popularly believed that new technology, particularly social media, is responsible for declining mental health among young people and a range of other social ills. But, says Dr Vuorre, concerns of this type are not new, nor are they well justified by current data.

Parents used to warn children that their eyes would turn square, if they watched too much television, and earlier generations were convinced listening to radio crime dramas...would inspire lives of crime

Parents used to warn children that their eyes would turn square, if they watched too much television, and earlier generations were convinced that listening to radio crime dramas, such as Dick Tracy (special agent) would inspire young people to turn to lives of crime.

Then, as now, says Dr Vuorre, the popular idea does not appear to be supported by hard evidence. The research, published last night, used data from three large surveys to look into the lives of more than 400,000 young people in the UK and US.

In these surveys, young people report on their personal use of technology and various mental health-related issues. Using this large data set, the team of researchers set about investigating the associations between adolescents’ technology use and mental health problems, and whether they have increased over time.

According to Dr Vuorre, these survey responses do not establish a smoking gun link between the use of technology and mental health issues, nor do they show that technologies have become more harmful over time.

‘We did find some limited associations between social media use and emotional problems, for instance,’ he says. ‘But it is hard to know why they are associated. It could be a number of factors [perhaps people with problems spend more time on social media seeking peer support?]. Furthermore, there was very little evidence to suggest those associations have increased over time.’

In fact, according to the new research, ‘Technology engagement had become less strongly associated with depression in the past decade, but social-media use had become more strongly associated with emotional problems.’

The study concludes, ‘The argument that fast-paced changes to social media platforms and devices have made them more harmful for adolescent mental health in the past decade is, therefore, not strongly supported by current data either.’

These results don’t mean that technology is all good for teens, or all bad, or getting worse for teenagers or not...it is difficult conclusively to determine the roles of technologies in young people’s lives

‘These results don’t mean that technology is all good for teens, or all bad, or getting worse for teenagers or not. Even with some of the larger data sets available to scientists, it is difficult conclusively to determine the roles of technologies in young people’s lives, and how their impacts might change over time.’

Dr Vuorre says. ‘Scientists are working hard on these questions, but their work is made more difficult by the fact that most of the data collected on online behaviours remains hidden in technology companies’ data warehouses.’

He adds, ‘We need more transparent research collaborations between independent researchers and technology companies. Before we do, we are generally in the dark.’

- ‹ previous

- 21 of 248

- next ›

Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance

Oxford citizen science project helps improve detection of antibiotic resistance The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance

The Oxford students at the forefront of the fight against microbial resistance  The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham

The hidden cost of AI: In conversation with Professor Mark Graham  Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year

Astrophoria Foundation Year: Dr Jo Begbie reflects on the programme’s first year World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era