Features

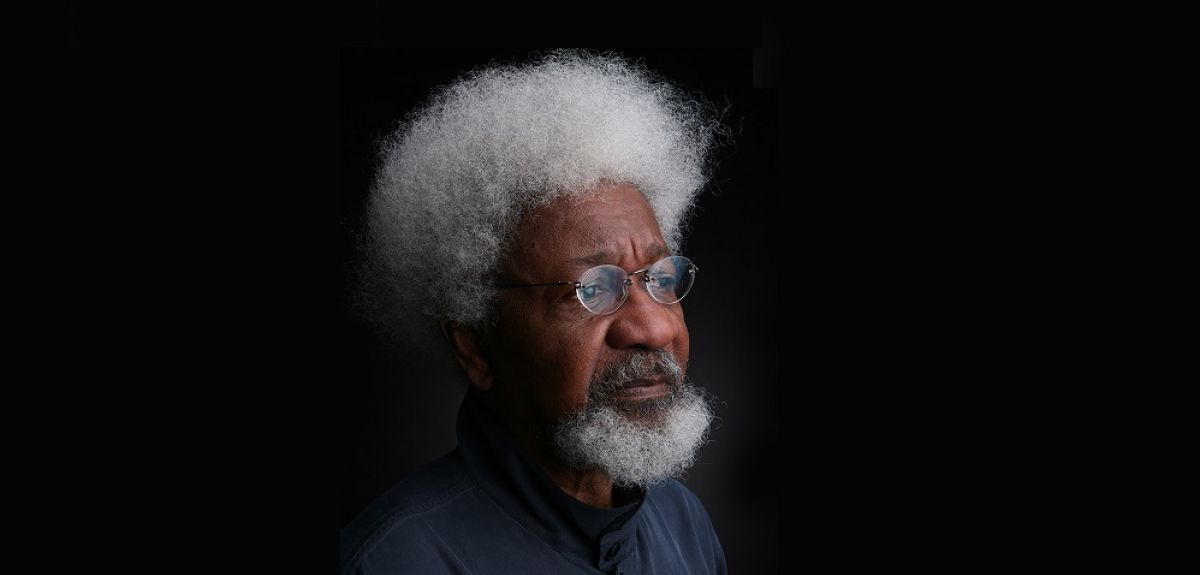

Brexit, Trump, Bob Dylan, pan-Africanism and Nigerian politics.

These were among the topics covered by the Nigerian Nobel Laureaute, poet, playwright and novelist Wole Soyinka when he spoke at Ertegun House recently.

The event was the inaugural Ertegun House seminar in the Humanities. The series brings into conversation members of the Ertegun House community and notable figures from the cultural, artistic, and academic worlds.

A video of the conversation is now available here.

Rhodri Lewis, Professor of English Literature and Director of Ertegun House, said the inaugural seminar was very successful and that Professor Soyinka offered “a tour de force of penetrating cultural commentary, delivered with measured but often playful outspokenness”.

The discussion was led by Professor Elleke Boehmer, who is Professor of World Literature in English at the University and the Director of The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH).

Mayowa Ajibade, an Ertegun Scholar who is studying for a Master’s in World Literatures in English and was also born in Nigeria, attended the talk. He said: ‘I grew up attending theatre performances of Soyinka’s plays in Lagos, Nigeria.

I think Soyinka writes with a palpable reverence for what James Baldwin, the American writer, calls "the force of life," in its many manifestations. I am particularly fascinated by the peculiar way Soyinka writes about food and the experience of eating, for instance.

‘I definitely agree with Soyinka's assessment, in the interview with Professor Boehmer, that African Literature in its current state is "robust", "varied", and "liberated" from its former anxieties about ideology.

'I particularly liked Soyinka's complex understanding of the way language functions - i.e. as both a "creative agency in itself" and as an instrument - an agent - that is regulated by the particular experience it refers to.’

The next events in the series are as follows:

Quentin Skinner (Barber Beaumont Professor of the Humanities at Queen Mary, University of London; winner of Balzan Prize), 5.30pm, 24 February 2017.

Stig Abell (Editor, Times Literary Supplement), 5.30pm, 4 May 2017.

The seminar takes place once a term and is open to all members of the University.

Advanced registration is required in advance. Podcasts of each event will be made available on the website.

Ertegun House provides the Ertegun Scholarship Programme with a high-profile presence at Oxford. It is the base for the study and research of the Ertegun Scholars, and serves as a centre of innovation and activity across the humanistic disciplines.

It was founded in 2012 following a donation from Mrs Mica Ertegun.

For more information on the Ertegun Scholarship Programme, visit the website.

Today is international languages day. But in the UK, modern languages is “at a crossroads”, according to an Oxford University professor. Katrin Kohl, professor of German Literature, says the perception of languages in schools and society is suffering.

Today, she and her fellow researchers have launched a major four-year research programme to investigate the interconnection between linguistic diversity and creativity. The project, called Creative Multilingualism, will explore how being able to speak more than one language can make us more creative. There is much more information about the planned research on the project’s website.

Professor Kohl tells Arts Blog a bit more about the project:

"Modern Languages is at a crossroads, and an ambitious research project will seek to give new impetus to the subject by putting creativity at the heart of it. This runs counter to the way languages are currently perceived, both in schools and in society – as a subject that consists merely of a bundle of practical skills. Research on Creative Multilingualism is designed to open up and showcase the cultural and cognitive riches associated with linguistic diversity, in order to reinvigorate the subject across the educational and academic spectrum and in society.

The researchers will be working on projects that are designed to investigate the creative roots of Modern Languages in the humanities, and explore the role of creativity in the interdisciplinary reach of languages as the communicative medium that characterises us as human beings.

In schools, Modern Foreign Languages has been suffering attrition for years, with the Government’s decision in 2004 to make inclusion of a language at GCSE optional leading to a significant and ongoing drop in take-up and in progression to A level. Together with league table pressures and the complexity and teaching-intensive nature of the subject, this has impacted negatively on Modern Foreign Languages departments in schools, and in turn caused some fifty university departments to close.

The falling number of Modern Languages graduates has contributed to an intensifying teacher shortage, with Brexit uncertainties now impeding recruitment from France, Spain and Germany. These factors have contributed to an unprecedented crisis in the subject, with a danger of meltdown especially in the state sector.

But we also need to ask ourselves why children and young people have been voting with their feet, and what’s been happening with the subject itself. We need go no further than the A level syllabus in force until this summer to find that the subject has been drained of academic substance. It restricts assessment to the ‘four skills’ of speaking, listening, reading and writing while reducing cultural content to a ‘carrier’ of language that is not assessed. This is like calling an A level subject “Maths” when actually it only consists of Applied Maths.

Moreover, at a time when the rise of global English has reduced the incentive to learn languages for native speakers of English, it has restricted the subject to its driest parts, with too few lessons per week to ensure sufficiently swift progress to sustain motivation. This reductive development has also opened up a gulf between Modern Foreign Languages in schools, and Modern Languages as they’re taught and researched in the humanities sections of Russell Group universities.

The Arts and Humanities Research Council is now investing an unprecedented £20 million into multi-institutional and interdisciplinary research as part of its Open World Research Initiative. This is designed to transform and invigorate Modern Languages research, and incentivise academics to work with partners that can help to raise the status of languages across UK society.

Four major collaborative research programmes led by Cambridge, King’s College London, Manchester and Oxford are being funded over the next four years to build a stronger and more vibrant identity for the subject, and to open up Languages to include ‘lesser taught’ ones in schools such as Mandarin and Arabic, and encourage cooperation between university departments in (European) Modern Languages and departments that teach Asian and African languages.

The Oxford-led programme entitled Creative Multilingualism includes researchers from Birmingham City University, Cambridge, Reading, SOAS, Pittsburgh, and the University of California, Santa Barbara. Together they have expertise in over 40 languages, which they will draw on as they conduct their research on the interaction and interdependence of linguistic diversity and creativity. They will be focusing on different aspects of language, ranging from the relationship between language and thought through to the interaction between languages in literary texts and theatrical performances.

A project on translation will investigate how moving from one language to another not only results in a transposed text, but also opens up new dimensions of meaning that lay hidden in the original. An empirical study conducted in UK classrooms will compare learning outcomes between functionally oriented tasks and tasks involving linguistic creativity.

A vital part of Creative Multilingualism is its work with partners including the British Council, the Association for Language Learning, English PEN, GCHQ, Business in the Community and a wide range of schools. In conferences, workshops, a Multilingual Music Fest, after-school clubs, a Linguamania event in January 2017 and a Road Show planned for 2019, participants of the programme will collaborate to showcase and explore linguistic creativity, make the value of community languages more visible, and give a more imaginative dimension to career choices involving languages.

Above all, they will seek to generate enthusiasm for the value of languages as a fascinatingly diverse medium of communication that allows us to express our cultural identities creatively, individually, and in original ways."

In Arts Blog we try to cover the latest research findings in the humanities and social sciences. But what about the story behind the research?

Here, Dr Alice Kelly, a Postdoctoral Writing Fellow in the Women in the Humanities Programme in TORCH | The Oxford Centre for the Humanities, explains how she made a recent discovery about Edith Wharton.

Dr Kelly found a typescript of a short story written by the Pulitzer Prize-winning American novelist, short-story writer and three-time Nobel Prize in Literature nominee. Titled 'The Field of Honour', the story is about the First World War.

"It was the title that originally caught my attention: an undated folder of writing marked ‘The Field of Honor’, catalogued between a number of drafts of short stories in the Edith Wharton Collection in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

Initially at Yale on a one-year Fox International Fellowship completing my doctoral dissertation on women’s First World War writing, I stayed on for a further two years, eventually teaching in the English Department and in the History Department of Wesleyan University, a nearby liberal arts college.

Working in the marble-clad Beinecke Library in the Wharton papers was the highlight of my time at Yale, and led to my discovery of this unknown First World War story and its significance in terms of Wharton’s war writings.

In an article published in this week’s issue of the Times Literary Supplement I provide a critical introduction and reproduce the story, which concerns Wharton’s anxieties about women in wartime and the relationship between America and France.

Not many people know that Wharton – the wealthy and globetrotting writer famous for her novels of high society, The House of Mirth (1905), Ethan Frome (1911), The Custom of the Country (1913) and The Age of Innocence (1920) – was also a war worker, reporter and author.

When the war broke out, Edith Wharton was living in Paris and very quickly became involved with relief efforts, establishing and managing four war charities, which would later gain her a number of military honours.

Although her writing slowed down during this period because of her extensive relief work, she still produced a considerable amount of war-related writing: a series of war reports published in American magazines and collected as Fighting France: From Dunkerque to Belfort in 1915; three short stories ‘Coming Home’ (1915), ‘Writing a War Story’ (1919), and ‘The Refugees’ (1919); the 1916 fundraising anthology The Book of the Homeless; and the novels Summer (1917), The Marne (1918) and A Son at the Front (1923), as well as a number of poems, newspaper articles and talks.

The story ‘The Field of Honour’ gives us a further demonstration of Wharton’s imaginative engagement with the war, particularly into the complexities of wartime politics and the role of women.

The story’s title, with ‘honour’ spelt in the English rather than American spelling (which was typical of Wharton) and meaning the battlefield or the field where a duel is fought, was originally a phrase referring to the medieval battleground, which became part of commonplace Great War rhetoric, and eventually represented post-war memorialisation efforts.

For First World War literary and cultural historians, it is impossible to read the phrase without thinking of its numerous wartime iterations. Reading the story for the first time – sitting in the library of the university which awarded Wharton an honorary degree in 1921 – I realized that the story was as rare as I’d originally thought, and gives us a greater insight into Wharton as a war writer.

After the neglect of Wharton’s war writing for a number of years, more recently there has been a critical reassessment taking place. My critical edition of Fighting France, Wharton’s collection of First World War reportage, will be published by Edinburgh University Press for its centenary in December 2015, along with restored original photographs and significant new archival material from Yale and Princeton.

My hope is that editions such as this one will contribute to new scholarship on Wharton’s war writing and the broadening canon of women’s First World War writing.

As a Women in the Humanities Postdoctoral Writing Fellow based at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), I am currently working on a broader study of modernist culture and war commemoration, examining the ways that writers, especially women writers, thought and wrote about death during and after the Great War.

I also run a twice-weekly Academic Writing Group for DPhil, postdocs and Early Career Researchers – which I’m sure Wharton, who wrote every morning in bed until noon, would have approved of."

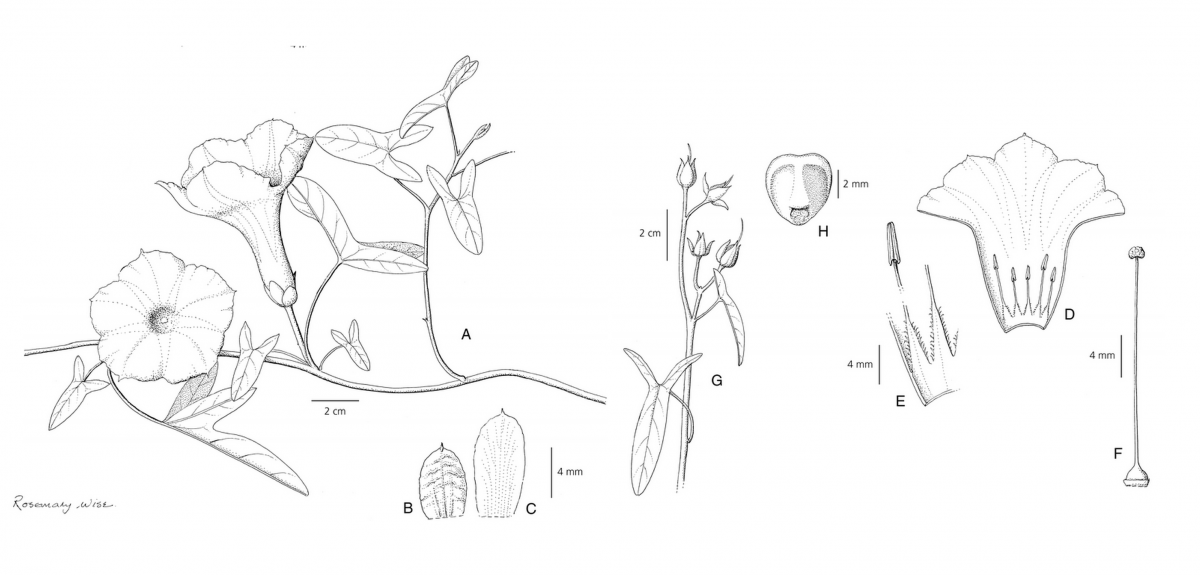

It can take botanists decades to accurately classify plants after they’ve collected and stored away samples from the wild. But now Oxford University researchers have developed a technique to streamline the process — and it’s already unearthing new species around the world.

In 2010, researchers from the Department of Plant Sciences, led by Dr Robert Scotland, published a paper that investigated how long it takes for plants to be described after they’ve been collected in the wild. The results came as a surprise: it turned out that just 14 percent of specimens were classified within five years, and on average it took 35 years for specimens to be recognised and classified as ‘new’. ‘People might imagine that researchers venture into the wild, point at something and say “that’s new”,’ explains Dr Scotland. ‘But it doesn’t work like that: mostly they get added to collections, then they're discovered at a later date.’

All the while, then, collected flowers sit dried and mounted on cardboard and placed in storage at herbaria for safekeeping. From their figures, the team estimated that of the 70,000 species of flowering plants thought to remain un-described, up to half may in fact sit in collections awaiting identification. Given the rate of discovery currently averages around 2,000 plant species per year, the team vowed to investigate whether there may be a way to expedite the process.

Generally, botanists perform one of two studies to describe plants in a given genus. The first, known as the Flora approach, is performed in a limited timeframe and describes all plant species in a particular country or region, using short descriptions and simple illustrations with no assessment of genetic differences taken into account. The second, referred to as the Monograph approach, takes a global view of all the species in a given genus, accurately demarcating each species and providing long descriptions, genetic analyses and detailed illustrations.

The latter is considered the gold standard in botanical taxonomy, not least because it provides a reliable means of identifying redundancies in existing classifications. But it often takes a long time to perform and involves intensive study. ‘It would be lovely to monograph the whole world, but that’s a pipe-dream,’ explains Dr Scotland. ‘Especially in the tropics, where there are too many plants, written about in too many places, often in too many different languages, with too much redundancy in existing names. The size of the task is just too big.’

Instead, the team thought there could be middle-ground between the two approaches. ‘We wondered if we might be able to combine some of the speed of a Flora approach with some of the rigour of a Monograph,’ explains Dr Scotland. ‘And we’ve ended up with what we call “foundation monographs”.’ The new approach combines the time-limited approach and short descriptions of the Flora approach with the genetic analyses and fieldwork of Monographs, enabling species to be uncovered quickly, but accurately. Crucially, it borrows content like drawings and genetic analyses, where they exist, from existing studies, in order to avoid duplicating work.

With a year of funding from Research Councils UK’s Syntax program, Dr Scotland’s team performed a one-year pilot study to create a foundation monograph for Convovulus (bindweed) — the first ever global study of the genus. It worked well: in 12 months, they recognised 190 species, including 4 new ones. ‘We showed that we’re able to catch the species that have slipped through the net in the past,’ explains Dr Scotland.

That was enough to help them secure a larger grant from the Leverhulme Trust to perform a three-year study of the Ipomoea (morning glories) genus — of which sweet potato is a member. Taking 1,500 samples from around the world, they sequenced DNA from the samples to identify key genes that can be used to create the genetic family tree of the species. Using those data, they were able to refute or corroborate existing species concepts, in the process identifying 18 new species and confirming the existence of 102 separate species in the genus from a single country, with many more to follow from other areas. From there, they were able to photograph and create detailed line drawings for those newly discovered species, finally publishing the foundation monographs in Kew Bulletin this September.

As far as Dr Scotland is concerned, we’re likely to see more species being identified like this in the future. “We’re probably seeing the end of the traditional approach to botanical taxonomy,” explains Dr Scotland.“That’s why we’re trying to do taxonomy in a time-efficient, clever way, at a scale that’s truly impressive.”

The most recent paper, entitled ‘Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae) in Bolivia’ is published in Kew Bulletin. The Convolvulus monograph, entitled ‘A foundation monograph of Convolvulus L. (Convolvulaceae)’, is published in Phytokeys. The illustrations for the research were funded by an NERC IAA award.

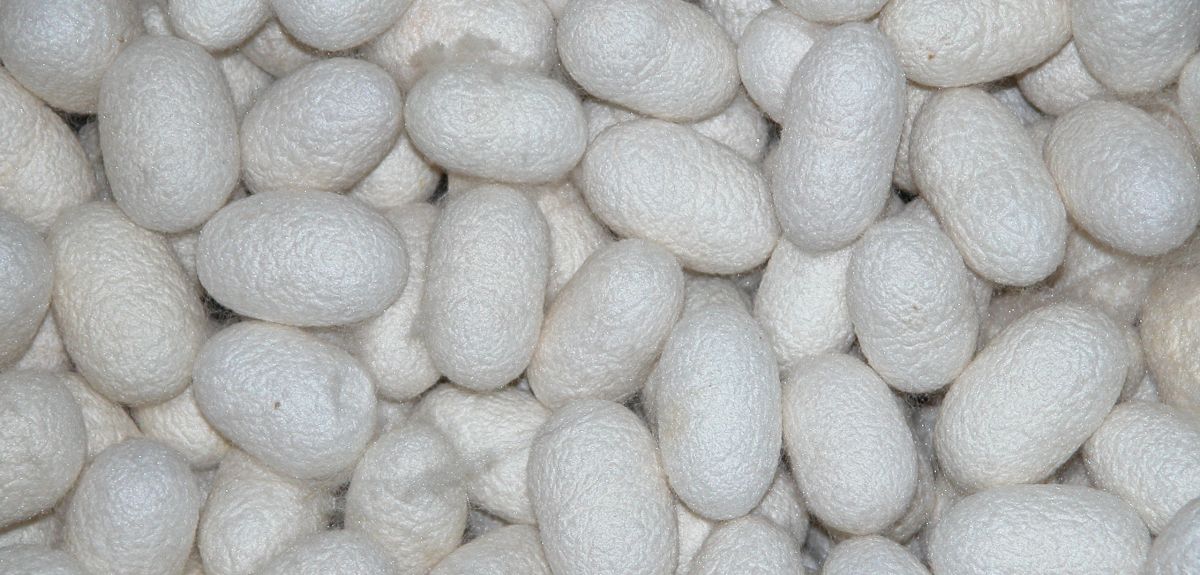

A traditional method of farming often praised for being environmentally sustainable actually releases 'significant' greenhouse gas emissions, an Oxford University study has found.

Integrated fish farming is common in aquaculture and a particular system from southern China combining silk production and aquaculture has been regarded as a prime example of multi-functional agriculture with a 'closed-loop' recycling process.

Organic residues from silk production are added to ponds to encourage the growth of phytoplankton, feeding fish. Waste accumulated in the pond sediments is removed and used to fertilise mulberry, which is in turn fed to silkworms.

A team led by Professor Fritz Vollrath of the Oxford Silk Group analysed the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions. Their results are to be published in the International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment.

'We have found that the formation of methane in pond sediments can be a significant source of emissions blamed for global warming,' said Professor Vollrath.

'Until now this method of small-scale farming has been held up as a shining example of environmentally-friendly farming. But our results suggest it may make an appreciable and previously underestimated contribution to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.'

He added: 'The effect is significant because carp are the most heavily farmed fish in the world, and commonly raised in fertilised ponds.'

- ‹ previous

- 5 of 8

- next ›

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences