Features

In 2014, IntoUniversity – a national charity that provides local learning centres to break cycles of disadvantage – opened the Oxford South East learning centre in Blackbird Leys in collaboration with the University of Oxford and Christ Church, Oxford.

Dr Rachel Carr, Chief Executive and founder of IntoUniversity, at the 10-year anniversary event.

Dr Rachel Carr, Chief Executive and founder of IntoUniversity, at the 10-year anniversary event.Set up to support young people reach their potential, over the past decade the centre has supported more than 5,000 local students from the ages of 7 to 18 through school and centre-based educational workshops, homework sessions, mentoring and holiday activities.

Ten years after it first opened its doors, IntoUniversity staff, volunteers, students, teachers and parents share what the centre means to them.

Benjamin Ashton, Centre Manager

Benjamin joined the centre staff in February 2023 as an after-school education worker and earlier this year took on the job of Centre Manager. ‘During the school day we workshop with partner primary and secondary schools – either at the centre or in school. After school, we are back in the centre and students come to us.’

IntoUniversity students successfully complete a group mentoring programme.

IntoUniversity students successfully complete a group mentoring programme.

Benjamin and his team continue to provide academic support to secondary students but are also helping them to focus on the options available to them when they leave school. ‘Our job isn’t to push our students down any particular path but to present them with all the options. Our main message is: ‘Pursue your interests and your passions’.’

He is clear about the importance of having a physical space for the centre, that is separate from school but rooted in the local community. ‘Community spaces for young people are disappearing. We may have an academic focus, but we can still be that community space,’ Benjamin says. ‘And Blackbird Leys is an incredibly strong community. It’s vibrant, multi-cultural and peaceful. I feel lucky to be part of it.’

Beatrice, Year 12 student

Beatrice, aged 16, has been coming to the centre once a week for four years for help with revision and to complete school assignments. ‘The staff are kind and welcoming, and full of knowledge when I don't know what to do.

Members of the IntoUniversity team with students at the Oxford South East learning centre.

Members of the IntoUniversity team with students at the Oxford South East learning centre.

‘I am quite an ambitious person but I would say that they push my ambition beyond its limits as they provide me with more information. I also like the events that are organised [in the school holidays] as they are quite fun!’

‘My advice to other young people thinking about attending the centre would be one hundred per cent come here – you won’t regret it’.

Ozioma, Year 12 student

Ozioma found out about IntoUniversity from a friend who came to the centre. Now in Year 12, she has been attending every week since Year 4. She uses her time at the centre to finish off her homework and do some revision. But it feels very different from school, Ozioma says.

‘I like how I get to see and talk to my friends and I like talking to the people who work at IntoUniversity,’ she says. ‘I get to meet new people here and have experiences about university and education that I might not get at school.’

‘Being part of IntoUniversity has made me care more about my education and made me want to go to university. Also, staff can always help with a question that I’m stuck on!’

Caroline Martin, Centre volunteer

‘There is such a positive vibe here,’ says Caroline Martin, who has been volunteering at the centre for the past four years. ‘If I turn up feeling a bit tired, the energy of the staff and children lifts my spirits.’

Year 6 students enjoying a workshop at the Natural History Museum in Oxford.

Year 6 students enjoying a workshop at the Natural History Museum in Oxford.

‘We follow a different topic each term; this term it’s Computer Science. But really, we are helping the children with their Maths and English. I usually sit with the kids who need extra help.’

Some children just find school overwhelming, Caroline says. ‘The education centre is not school. But it is somewhere people who might be struggling at school can get a little extra help. For many of them it also opens their horizons and that’s a great aim.’

Omotayo, Parent

Omotayo understands the opportunities education offers – and she believes the support of the centre staff in Blackbird Leys is enabling her children to take up opportunities that weren’t available to her.

All three of her children have benefited from the centre; her daughter and younger son still attend regularly.

‘It opened my eyes. If your kids are struggling, there is a place for them to go,’ she says. ‘IntoUniversity has helped my children with all aspects of life. It is teaching them team work and leadership skills. It has helped them focus and boosted their self-confidence.’

‘My youngest child is 10 and he went on an IntoUniversity trip to Southampton University during the summer. Now he wants to go to university too.’

Omotayo’s older son has secured a full scholarship to Marlborough College through IntoUniversity. It is an amazing opportunity for him, Omotayo recognises, and one he wants to share, thanks to the care and support he received from staff and volunteers at IntoUniversity in Blackbird Leys.

‘My children are ready to give back. My son knows he is on a bursary and he knows that he also wants to raise opportunities for others.’

Sarah Bennett, Primary school teacher

Centre leader Benjamin Ashton with students on a trip to Science Oxford in Headington.

Centre leader Benjamin Ashton with students on a trip to Science Oxford in Headington.

Sarah worked at the centre for three years before completing her teacher training qualifications, and now works as a Year 4 class teacher in one of the centre’s partner schools, Church Cowley St James.

‘From a teacher’s perspective, it’s great that IntoUniversity introduces our pupils to the idea of university as one of the many options open to them after school,’ Sarah says.

‘Our cost-of-living crisis means many families don’t often have these conversations with their children. But IntoUniversity feeds their curiosity early and staff explain briefly how the funding works so that it doesn’t seem too scary, and it opens parents’ eyes to the possibilities for their children.’

Find out more about IntoUniversity here.

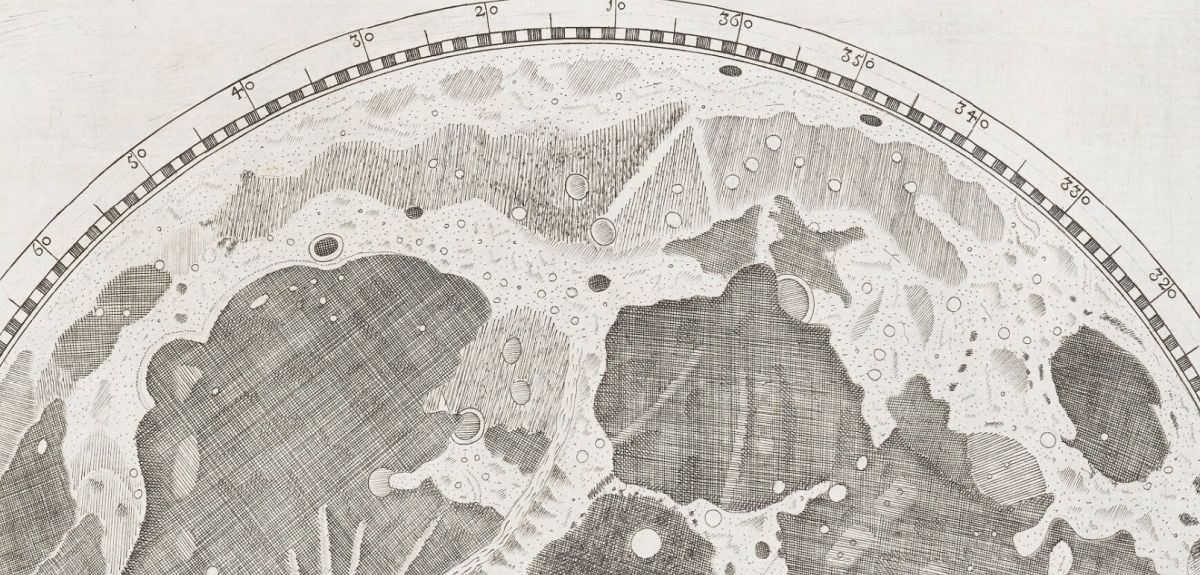

In 1647, a self-taught astronomer and brewer from Gdańsk changed the way humanity saw the Moon by creating the first detailed map of the lunar surface. Now, nearly four centuries later, the Bodleian Libraries have brought Johannes Hevelius’s Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio ('Selenography, or a Description of the Moon') into the digital age – allowing anyone, anywhere, to explore the world’s very first lunar atlas.

Portrait of Johannes Hevelius. Date: 1646 – 1649. Credit: Rijksmuseum.

Portrait of Johannes Hevelius. Date: 1646 – 1649. Credit: Rijksmuseum.Selenographia was pioneering in its accuracy, showing that Moon’s surface was far from a blank canvas, but a mosaic of craters, valleys, and mountains. The complete atlas is made up of 111 plates and engravings, showing the Moon in every phase, besides a composite map depicting all of the Moon’s features as if lit from the same direction, which became the model for later lunar maps.

This remarkable artefact is of high interest to astronomers, lunar enthusiasts, and historians of science worldwide. Up to now, those wishing to view it would have to come to the Bodleian in person and arrange for the item to be brought out specially. But now a fully-digitised, open-access version is available through Digital Bodleian, the Library’s showcase platform for digitised collections, for anyone to admire, anytime – even from the comfort of their own home.

Judith Siefring, Head of Digital Collections Discovery at the Bodleian, says: ‘The Bodleian is committed to democratising access to its really amazing collections, and digitising as many manuscripts, archives, and rare books as possible forms a large part of that. Around 75% of those who use Digital Bodleian are based outside the UK, demonstrating that we are serving an international audience.’

A remarkable object from a remarkable man

A page from Selenographia: sive, Lunæ descriptio. From Bodleian Library Arch. H c.12.

A page from Selenographia: sive, Lunæ descriptio. From Bodleian Library Arch. H c.12. Producing a lunar atlas was one of Hevelius’s first major endeavours, the other being a catalogue of 1564 stars. Over five years, he meticulously drew the Moon each night from observations by eye and through his telescopes, then engraved his observations in copper the following morning.

‘Considering the equipment he was using, the level of detail of the map is mind-boggling,’ adds Malgorzata. ‘Rudimentary maps of the Moon already existed, but none as detailed as this, and none in the form of an atlas. Hevelius took it upon himself to name various aspects of the terrain, indicating that he discovered many details that were not known about previously.’

Many of the names Hevelius gave to lunar characteristics are still used now (such as ‘Alps’ for lunar mountains), and a large crater on the edge of the Ocean of Storms also bears his name today. When the volume was published in 1647, it brought Hevelius fame and prestige as an astronomer, but perhaps the greatest testament to Selenographia is that it stood as the ultimate lunar reference manual for over a hundred years.

Digitising a treasure

Photographer Ellie Harris in the Bodleian Imaging Studio.

Photographer Ellie Harris in the Bodleian Imaging Studio.The project to digitise Selenographia took shape after the presentation copy was displayed for a group of visiting directors of Polish museums and art galleries. Through collaborations between the Bodleian, the Polish Ball, and the Centre for Democracy and Peace Building, a private donor came forward to fund the digitisation. Malgorzata recalls: ‘Mr Karol Sieniuc was so impressed by the Bodleian’s collections and how it strives to make them available to everyone, that he did not need much persuasion to sponsor the digitisation of a Polish treasure that is Selenographia.’

Selenographia was digitised in the Bodleian Libraries’ dedicated studio, one of the country’s leading imaging facilities. This is equipped with high-resolution cameras and bays tailored to digitise different types of material, from papyrus and maps, to manuscripts and rare books. Over the course of a week, the atlas was captured in just under 800 images at 600-dpi resolution, each checked and aligned using specialist software, then linked to bibliographic data before publication online. The resulting digital version allows users to leaf through Selenographia virtually and zoom in to explore even the finest engraved details, revealing the Moon as Hevelius first saw it nearly four centuries ago.

Connecting communities

A page from Selenographia: sive, Lunæ descriptio. From Bodleian Library Arch. H c.12.

A page from Selenographia: sive, Lunæ descriptio. From Bodleian Library Arch. H c.12. ‘Digitising collections fulfils many key purposes,’ says Judith. A major one is preservation, of course. Interestingly, much of Hevelius’s observatory, instruments, and books were destroyed by a fire in 1679, and the original copper plate used to print Selenographia was sold after his death and turned into a teapot. ‘Another key purpose is engaging diverse audiences with our collections in new ways, and opening up the knowledge they contain to the world,’ adds Judith.

Digital Bodleian has already made over 1.3 million images of rare manuscripts, maps, and printed works freely available online. Previous major initiatives have included partnerships with the Vatican Library (Greek and Hebrew manuscripts and early printing) and with the Herzog August Bibliothek (medieval Manuscripts from German-speaking Lands), both generously funded by the Polonsky Foundation. Other projects have included Literary Manuscripts (funded by the Tolkien Trust) and Education & Activism: Women at Oxford 1878-1920, a collaboration with several Oxford colleges.

You can find the digital version of Selenographia here.

From inspiring science days for local schools to educational festivals for young people, targeted outreach programmes, the launch of a new online academic enrichment platform, and support for UK-wide access initiatives; across the collegiate University, Oxford is finding new and innovative ways to engage with talented students across the UK from all backgrounds.

Oxford colleges have worked with The Brilliant Club – a UK-wide charity that aims to improve opportunities for students from less advantaged backgrounds to access higher education – for a number of years, hosting ‘graduation’ ceremonies for hundreds of young students completing the Scholars Programme.

Students visit Oxford colleges and learn more about university life. (c) The Brilliant Club

Students visit Oxford colleges and learn more about university life. (c) The Brilliant ClubIn 2024/25, twelve of Oxford’s colleges formally joined The Brilliant Club’s Scholars Programme, which connects state school pupils, aged 8 to 18, with PhD students who share their subject knowledge and passion for learning.

The scheme enables participants to experience university-style learning through seven in-school tutorials delivered to a small group of pupils by trained PhD tutors, usually based on their own research. The charity has built a community of over 1,200 tutors made up of current PhD students, early career researchers and PhD graduates.

The Scholars Programme introduces pupils to the world of academic research and is designed to help them build confidence, curiosity and a sense of belonging in higher education. It includes a challenging final assignment and for many the experience culminates in their own graduation celebration at one of the University’s colleges.

In 2024/25 more than 1,700 school pupils from Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Bristol and London either worked with an Oxford researcher or attended a graduation event at an Oxford college.

Dr Matthew Williams work with school groups in his role as Access Fellow at Jesus College

Dr Matthew Williams work with school groups in his role as Access Fellow at Jesus College

The scheme, Dr Williams says, is also a valuable experience for Oxford’s PhD students who receive expert training to develop and hone their pedagogical skills, gain sustained teaching experience, develop research communication skills, and have an opportunity to communicate their research to a non-specialist audience.

Five Oxford PhD students took part in the programme in 2024-25, with specialisms ranging from genetics to archaeology and courses covering subjects as diverse as the healthy heart, the evolution of biodiversity, and neuroscience and AI. ‘Increasingly, PhD students are encouraged to think about public engagement and impact, and this helps them develop key communication skills — being able to explain complex ideas to a 15-year-old is a great test of understanding.’

Abby Williams, a PhD student in the Department of Biology, said, ‘During one of my first lessons we were looking at the animal evolutionary tree, and one of my students had a ‘lightbulb moment’ – we were discussing how humans are more closely related to starfish than insects, and the student said, ‘Miss, that’s really cool!’. That moment felt like a massive teaching win for me, and I hope that the student felt inspired to learn more about the natural world.’

Students visited Oriel College and graduated from the programme with a formal ceremony. (c) The Brilliant Club

Students visited Oriel College and graduated from the programme with a formal ceremony. (c) The Brilliant ClubDr Williams says the partnership demonstrates how collaboration can deliver genuine impact; ‘Partnering with The Brilliant Club allows Oxford to make a tangible difference in the lives of young people while giving our own researchers meaningful opportunities to share their work. Through initiatives like this, Oxford continues to work with schools, colleges and charities across the UK to inspire the next generation of students to consider Oxford as a place for them.’

Find out more about Oxford University's access programmes - Oxford Access | University of Oxford.

At a time when translators are facing unprecedented challenges in the face of artificial intelligence, a new graduate course will explore and celebrate translation as a creative endeavour in which the role of the human will always remain essential.

From ancient texts and contemporary novels to performance theatre, film and television, translation shapes the way we experience stories from past and present and from around the world.

Oxford’s undergraduates have long studied academic translation within Modern Language degrees, but to-date there has been no provision for graduate students. A new Masters in Creative Translation has been launched to fill this gap, coinciding with an important moment when the translation landscape is shifting and adapting to technological change.

Led by Professor Karen Leeder in the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages, the course also reflects a growing appreciation for translation as both a field of research and a creative discipline that requires not only linguistic skill, but also imagination, interpretation, and cultural sensitivity. 'It’s increasingly recognised as a literary art form,’ says Professor Leeder, herself a prize-winning translator. ‘We’re seeing a real coming of age for the field.’

The course will be based in the University’s new Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities, which brings many of Oxford’s internationally recognised Humanities faculties together under one roof, with new spaces for teaching, performance, and film. ‘There is a considerable creative reservoir and appetite for this course at Oxford. This is an exciting opportunity for students who will be joining a hub of creative activity,’ says Professor Leeder.

Distinct from academic translation, creative translation explores the history, theory and methodologies of translation and interprets not just meaning but voice, considering tone, rhythm, and emotion. In recent years, campaigns such as #NameTheTranslator have sought to credit translators alongside authors on book covers and prize lists, helping to foreground their role as artists and creative interpreters.

We hope this course will...serve as a reminder that the ability to imagine, interpret, and connect across languages and cultures remains a distinctly human endeavour.

Professor Karen Leeder

As well as developing their own practice as a translator, students on the Creative Translation course will be introduced to a range of materials, from the earliest translations of ancient texts to the dilemmas of AI, examine how translations differ, and explore areas such as translation for performance, adaptation, early modern translation, translating the untranslatable, multilingualism, as well as focussing on specific languages, genres, and periods. The course will include a programme of regular industry sessions with visiting creatives and experts.

The timing of the course is not coincidental. In the UK there is a growing demand for skilled translators to support thriving creative industries. It also comes at a time when the human role in translation is more important than ever, says Professor Leeder.

The course will be based at the new Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities

The course will be based at the new Schwarzman Centre for the HumanitiesProfessor Leeder is pragmatic. ‘All art forms are under threat from AI,’ she says, ‘but AI is used in translation, and we must find ways to work productively with it.’ The course will encourage students to critically engage with these technologies while also recognising their limits and learning to identify what makes for ‘good’ translation.

She points to some foreign language television series which have gained global followings in recent years, but in which mistranslating (or machine translating) in subtitling is a common issue. This has led to ‘lost in translation’ moments caused by words being incorrectly translated, paraphrasing, a lack of understanding of cultural context, nuance around characters being lost, and a failure to successfully deal with humour.

Human translators, Professor Leeder explains, will always bring something that machines cannot replicate. ‘AI can’t deal with metaphor, idiom, or the stresses of word order and how this can change meaning. This is where the value of human translation lies.’

‘There needs to be a re-evaluation of the role of the human translator,’ she goes on. ‘It’s so important to champion their role in the future of publishing when authorship itself is under threat.

‘We hope this course will not only prepare graduates to make a real impact in our creative industries, supporting a new generation of translators as creative thinkers, collaborators, and innovators, but will serve as a reminder that the ability to imagine, interpret, and connect across languages and cultures remains a distinctly human endeavour.’

To mark the European Day of Languages, The Queen’s Translation Exchange (QTE) – run by The Queen’s College – has launched the sixth Anthea Bell Translation Prize for Young Translators.

Designed to promote language learning in schools and arrest the decline in the study of modern languages, the prize is inspired by the work of the translator Anthea Bell who helped open up the world of Asterix the Gaul to millions of children in the UK.

Students taking part in The Queen’s Translation Exchange © Edmund Blok

Students taking part in The Queen’s Translation Exchange © Edmund Blok

One teacher has told us that running the Anthea Bell has enabled the school to run an A level language class for the first time in two years.

Dr Charlotte Ryland, The Queen’s Translation Exchange Founding Director

The prize is free to enter and currently runs in six languages: French (into Welsh and English), Spanish, German, Italian, Mandarin and Russian. It also offers a range of texts to translate including poetry, fiction and non-fiction, and has become increasingly popular. Last year 22,000 learners from 412 schools took part, while more than three in four teachers involved in the prize said it had helped raise the profile of languages in their schools.

Although the prize is being launched this month, it won’t officially open to entrants until February. ‘This is because it isn’t a one-off event. We want teachers to integrate the Anthea Bell into their teaching throughout the year,’ says Dr Ryland.

To enable this, QTE provides more than 100 teaching packs that teachers can request when they register for the prize. Packs provide lesson plans based on authentic texts and include a range of resources such as teacher notes, worksheets, glossaries, videos and extension activities. Care has been taken to link resources to the curriculum while preparing students to enter the prize when they will be expected to complete tasks in the classroom, without teacher support.

Dr Charlotte Ryland, QTE Founding Director © John Cairns

Dr Charlotte Ryland, QTE Founding Director © John Cairns

Entries are then judged for their accuracy and creativity by Oxford University languages students and professional literary translators. This is initially done geographically, with area winners selected for each level and language and put forward for the national awards. All winners, runners up and commendees receive a certificate and their names are published on the Queen’s College Website. UK winners also receive a book prize.

It is impossible to underestimate the value of languages when it comes to positively influencing our view of contrasting cultures.

Dr Charlotte Ryland

It's not just that the prize makes language learning more engaging for their students of all ages that attracts teachers to the Anthea Bell – although it does. They also recognise that it develops their students’ problem solving and critical thinking skills. More importantly, it has offered many of them a huge uplift in self-confidence and self-belief and a sense of opportunities they had never considered within their reach. For some young participants, it is the first time they have talked about the possibility of going to university.

Dr Ryland takes it a step further. She believes that encouraging more people to study languages – at whatever level – fosters cultural inclusion and diversity. ‘It is impossible to underestimate the value of languages when it comes to positively influencing our view of contrasting cultures,’ she says. ‘Young people who immerse themselves in languages are better placed to appreciate the cultural diversity around them and its value to wider society.’

- ‹ previous

- 2 of 253

- next ›

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis

What Louise Thompson’s campaign tells us about the national maternity crisis Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon

Celebrating 25 Years of Clarendon  Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford

Learning for peace: global governance education at Oxford  What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans

What US intervention could mean for displaced Venezuelans  10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact

10 years on: The Oxford learning centre making an impact Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars

Oxford and The Brilliant Club: inspiring the next generation of scholars New course launched for the next generation of creative translators

New course launched for the next generation of creative translators The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools

The art of translation – raising the profile of languages in schools