New research reveals relationship between particular brain circuits and different aspects of mental wellbeing

Researchers at the University of Oxford have uncovered previously unknown details about how changes in the brain contribute to changes in wellbeing.

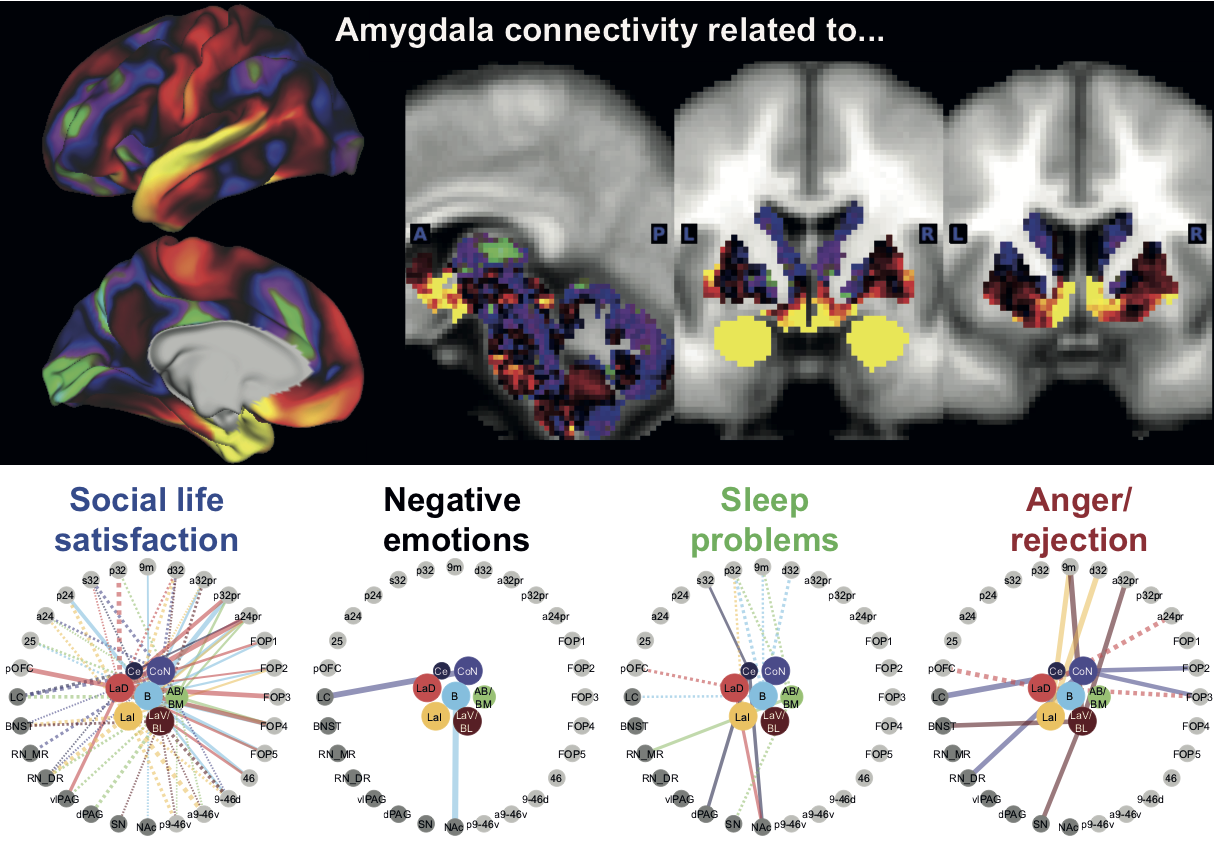

Associate Professor Miriam Klein-Flügge and colleagues looked at brain connectivity and mental health data from nearly 500 people. In particular, they looked at the connectivity of the amygdala – a brain region well known for its importance in emotion and reward processing. The researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging to consider seven small subdivisions of the amygdala and their associated networks rather than combining the whole region together as previous studies have done.

The team also adopted a more precise approach to the data on mental wellbeing, looking at a large group of healthy people and using questionnaires that captured information about wellbeing in the social, emotional, sleep, and anger domains. This generated more precise data than many investigations which still use broad diagnoses such as depression or anxiety, which involve many different symptoms.

The paper, published in Nature Human Behaviour, shows how the improved level of detail about both brain connectivity and wellbeing made it possible to characterise the exact brain networks that relate to these distinct aspects of mental health. The brain connections that mattered most for discerning whether an individual was struggling with sleep problems, for example, looked very different from those that carried information about their social wellbeing.

Associate Professor Miriam Klein-Flügge of the Department of Experimental Psychology, based at the Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging (WIN), said: ‘Understanding how changes in the brain relate to changes in wellbeing is an important step in the journey towards more targeted mental health treatments.'

‘We looked at the brain in much finer subdivisions than previous research, which more closely resembles how the brain is organised, and our findings indicate that it may one day be possible to develop very precise and non-invasive ways to target specific areas of the brain, making future treatments much more refined.’

The researchers also found that the nature of the identified brain networks differed. For example, they discovered that connectivity in the evolutionarily older subcortical circuits was related most strongly to the tendency to experience negative emotions, while connectivity of the amygdala with both newer cortical and older subcortical circuits clearly contributed to social wellbeing.

The findings indicate the potential benefit of considering mental wellbeing and the involved brain networks at a finer scale than before – a scale that more closely matches the brain’s functional organisation. Although more research is needed, in the future it might be possible to target treatments to the brain circuits most relevant for an individual’s key symptoms. This possibility is becoming more tangible with current progress in non-invasive deep brain stimulation methods such as ultrasound, for example.

The full paper, ‘Relationship between nuclei-specific amygdala connectivity and mental health dimensions in humans’, can be read in Nature Human Behaviour.

New research shows high temperatures affect sex ratios at birth

New research shows high temperatures affect sex ratios at birth

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy offers new insight into preeclampsia prevention

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy offers new insight into preeclampsia prevention

Expert Comment: Should the UK relax clean energy targets?

Expert Comment: Should the UK relax clean energy targets?

Existing hospital analysers offer a low-cost method to screen for fake vaccines

Existing hospital analysers offer a low-cost method to screen for fake vaccines