Project for whole genome sequencing of extinct flightless birds

The University of Oxford’s Department of Zoology today announces it will begin whole genome sequencing of extinct flightless birds, including the dodo and its sister taxa, the Rodrigues solitaire.

The whole genome sequencing project is being funded by a donation from Joseph Hernandez, a healthcare and biotech entrepreneurial leader, who has shown a continued interest in the dodo and in answering question about evolutionary trajectories of flightless birds.

Professor Tim Coulson, Joint Head of the Oxford Department of Zoology, says, ‘Discovering Joe’s love of the dodo was completely fortuitous, but it led to him viewing the Oxford dodo, which is the best-preserved dodo specimen in the world.

‘His generous offer to sequence sub-fossils of the dodo and related flightless birds has provided a wonderful opportunity to bring together experts across Oxford University to gain unprecedented insight into the genetic mechanisms underpinning why many island birds, such as the dodo, lose the ability to fly. The work will start later this month, with the first results expected before the end of the year.’

Associate Professor Sonya Clegg, from Oxford’s Zoology Department, who is leading the work, says, ‘Unravelling the genomes of the dodo and Rodrigues solitaire will provide a window to understand evolution of these extinct island species that is comparable to insights we have from living ones.’

A wonderful opportunity to bring together experts across Oxford University to gain unprecedented insight into the genetic mechanisms underpinning why many island birds, such as the dodo, lose the ability to fly

Joseph Hernandez says, ‘I’ve always had an interest in the evolution of flightless birds and the dodo has been a point of interest for many years despite not being seen on this planet since the late 1600s. I am thrilled to provide the funding to the Oxford Department of Zoology so that these scientists can begin answering questions about how these birds evolved until their extinctions centuries ago.’

The researchers hope to produce a suite of comparative genomes that will be used to test the idea of convergence at the level of the genome for flightlessness and other common features found in island forms. Additionally, the genomes will be available for research to further examine connections between phenotypes and genotypes across the avian tree of life.

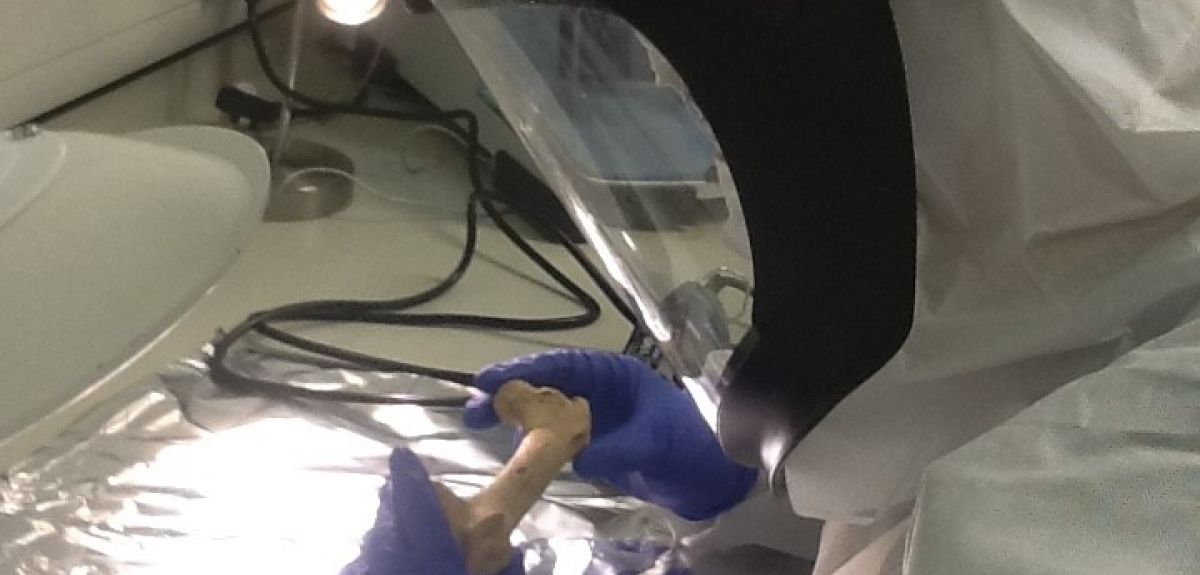

Dodo bone samples: genome sequencing

The Department of Zoology has secured access to bone samples from five dodo (Raphus cucullatus) and five solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria) subfossil bones, held by the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, for the whole genome sequencing. The team will take two bone powder samples from each bone, one for the genomic analysis and one for radiocarbon, or 14C, dating.

All five dodo bones and one of the solitaire bones have pre-existing damage sites (cut-or-drill marks in the central shaft regions), which will result in two samples being taken from each bone adjacent to these sites to minimize new impacts and damage. The remaining four solitaire bones have not been previously sampled.

The first sample will collect approximately 100 milligrams of bone powder, sufficient for deep sequencing of the endogenous DNA. The second sample will collect approximately 80 milligrams of bone powder and will allow for sufficient collagen extraction for radiocarbon dating.

The work is being led by Associate Professor Sonya Clegg, an expert in bird evolution, from Oxford’s Zoology Department, with expert collaborators in Archaeology, the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, Earth Sciences and Plant Sciences.

Oxford and Serum Institute of India sign IP license agreement to advance NipahB vaccine candidate

Oxford and Serum Institute of India sign IP license agreement to advance NipahB vaccine candidate

New research reveals why some oesophageal cancers are so hard to treat

New research reveals why some oesophageal cancers are so hard to treat

New research reveals how development and sex shape the brain

New research reveals how development and sex shape the brain

Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences designated as the WHO Collaborating Centre on Primary Health Care

Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences designated as the WHO Collaborating Centre on Primary Health Care

The King presents The Queen Elizabeth Prizes for Education

The King presents The Queen Elizabeth Prizes for Education