Sex, skinks, and personality

When it comes to spatial learning males are better than females, and bold and shy individuals are better than average ones, at least if you're a lizard.

The findings, from a new study of the Easter Water Skink (Eulamprus quoyii) - a lizard that lives throughout Eastern Australia and can grow over 12cm long - are the first evidence of sexual learning differences in a reptile. A report of the research is published in this week's Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

A team led by Oxford University and Macquarie University, Sydney, scientists took 64 skinks, 32 males and 32 females, and released them into a series of strange environments to investigate how differences in personality influence how they learn. These environments included features they would like, a 'warm' refuge made of a box with three entrances heated by an incandescent bulb, and features they wouldn't, a 'cold' refuge made of a similar box chilled with ice packs.

By introducing the skinks to simulated predator events (being chased away into a refuge) the researchers determined which returned quickly to bask in a warm refuge ('bold' lizards) and which took longer than average to return ('shy' lizards). They then tested the lizards once a day for 20 days in a setting where they were again exposed to simulated predatory attacks and given a choice between a safe refuge (chasing stopped) and an unsafe refuge (the refuge was lifted and chasing continued) that were always located in the same place.

'We found that male lizards were better at this spatial learning task than females, with twice as many males as females learning the spatial task within 20 trials,' explains Pau Carazo of Oxford University's Department of Zoology, who led the research.

'While this is the first evidence ever of sexual learning differences in a reptile, we believe it reflects the fact that males are forced to spend more time moving through their environment in search for females or patrolling their territory to guard it against other rival males. We also show that, across the sexes, the boldest and shyest individuals were overall better learners than intermediate individuals.'

According to the team this is the first evidence that individuals at the extreme ends of a personality axis are better learners than individuals with intermediate personality traits. This does not fit well with current theories about how personality and learning may co-evolve: the team proposes the idea that spatial learning ability and personality are both linked with male reproductive strategies.

'In Eulamprus, as in many other lizard species, male lizards exhibit two alternative reproductive strategies. Some male lizards defend territories, which not only requires them to be bold but also to constantly patrol their territory and remember rival males at its boundaries (which would favour good spatial learners),' Pau tells me.

'In contrast, other males adopt an alternative sneaker strategy whereby they are forced to navigate over long distances (which would also favour good spatial learning abilities) to sneak into other males' territories and try to mate with resident females. Because these males do not defend territories and normally avoid fights, they are likely to be shy.

'We suggest that males that are particularly good at either of these two strategies are likely to be good spatial learners and are either extremely bold or extremely shy individuals. This new hypothesis may help to explain how personality and learning co-evolve, and to understand the evolutionary processes that may lead to the striking individual differences in learning than can be observed in most animal species studied to date.'

A report of the research, entitled 'Sex and boldness explain individual differences in spatial learning in a lizard', is published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Tamiflu: an analysis of all the data

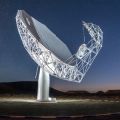

Tamiflu: an analysis of all the data MeerKAT is shape of things to come

MeerKAT is shape of things to come Why males stray more than females

Why males stray more than females