To inspire more young people to pursue science careers, representation is key

Thursday 8 March marks International Women's Day, a global commitment to honouring the cultural, social, economic, political and academic contributions of women. Over the next few weeks, Science Blog will start the celebrations by shining a light on the incredible women of Oxford and some of their achievements.

Despite the different backgrounds, motivations and journeys that brought them to the University, each of the women featured have one important thing in common: success. In a field where women are still woefully underrepresented, they are rapidly carving their own niche, inspiring budding scientists of tomorrow in their own way.

Science Blog meets Layal Liverpool: 'I can't wait until there are no more firsts'

Representation is often discussed in today's society, but it means something different to everyone. Its impacts though are undisputed, taking hold from a young age and rippling out to shape the rest of our lives. Lack of representation can distort our understanding of people who are not like us and prevent some from imagining themselves in a situation - blocking their talent from developing into an opportunity in the process.

One person who understands this well is Layal Liverpool, a 24-year-old DPhil student investigating virus-host interactions at the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine. In addition to her studies, Layal is a committed science communicator and STEM ambassador. She shares her experience as a young woman of colour navigating the world of academic science.

I've been to a few career seminars, but only ever seen one woman of colour presenting. I can't wait until that changes and there are no more firsts.

What inspired you to pursue a career in science?

Even at the age of five I had a natural interest in learning new things and solving problems, to the point that I was obsessed with encyclopaedias - my parents were worried I wouldn't read anything else.

I also had a great A-level biology teacher, who had a PhD and happened to be a woman. Having her in my life meant that I never saw science as not being for girls.

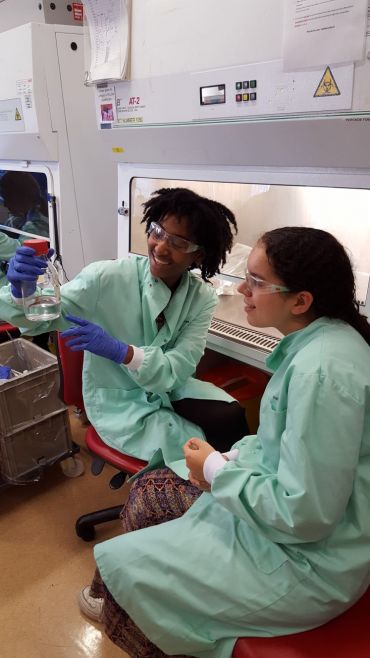

Layal (left) hard at work in the lab with a visiting student, at the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine. Image credit: OU

Layal (left) hard at work in the lab with a visiting student, at the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine. Image credit: OUHow did you come to specialise in infectious diseases?

My parents are originally Ghanaian, so as a child I spent a lot of time there. Ghana was significantly affected by the HIV pandemic and growing up I saw marketing about using condoms and how to stop the spread of HIV. I was just a kid and had no idea what it was, but I was curious and wanted to find out more. During my bachelor's degree at UCL, I took a brilliant course on infection and became absolutely fascinated by viruses in particular. I find the way the human body works - particularly disease and why things go wrong - fascinating. I chose to study immunity against viruses in general, to learn about multiple infections.

Viruses are not even alive and yet they can cause such complicated diseases - that fascinates me.

What are you working on at the moment?

At the moment I am building on a lab project established by a previous researcher, aiming to better understand how viruses are detected when they first invade our cells.

Do you think diversity is an issue in STEM?

Absolutely. Just the other day I attended a career seminar - I've been to a few of these, but this was the first time I had ever seen a woman of colour presenting. I felt so inspired and was really struck by the fact that she was the first highly successful woman of colour that I had seen giving one of these seminars. I can't wait until that changes and there are no more firsts.

It was really interesting to hear from her about how much the world has changed since she first started working - for example, she shared some past experiences of overt discrimination in the workplace.

My advice to anyone considering a career in science is don't let self-doubt stop you. The only way you definitely won't get in is by not applying.

Would you say that role models are important in science?

I've been fortunate to have wonderful role models so far that I truly appreciate, but very few have looked like me and I hope that changes. I think that would be really great for the younger generation because representation matters.

I love my field and feel very fortunate to be here at Oxford, but if I could change one thing about my experience it would be to have and interact with more women like me at different stages. The University has a mentoring scheme, and I think it would be great if that ran across all levels. For example, as a doctoral student I could be mentored by someone more senior, but equally I could mentor new applicants and people just starting and help them navigate the University.

How would you describe your experience at Oxford?

I am constantly grateful to be here, and get to work alongside world-leading researchers, but I think university is still a very elite environment, and there is a way to go to improve diversity - especially at my level. I have noticed that the higher you go within the University, the diversity decreases, which is a shame. There are a lot of talented people working in STEM who I think could be there, but the opportunities need to be available to get them there.

If I could change one thing about my experience it would be to have and interact with more women like me at different stages.

Are there any changes that you think would make a difference?

More representation is not easily achievable, unless more young people are inspired to pursue science careers. I have volunteered at Saturday Science Club, a science activity programme for families run by Science Oxford, and my hope is that when the children in the group are asked 'what does a scientist look like?' they will say 'anything'.

What does being a woman in science mean to you?

I view my studies as an important step along the road of using scientific research to benefit society. It wasn't that long ago that women didn't have these opportunities. I like to reflect and recognise how far we've come, but also how far we still have to go. There are some incredible women doing incredible things in science and I feel fortunate to have the opportunity to work alongside them and contribute.

How did you first get involved with science communications?

I actually auditioned for FameLab, where you have to explain a scientific concept of your choice in three minutes to a general audience. I spoke about HIV and made it to the regional final. A key element of understanding something is being able to explain it in simple terms, and the experience really improved my science communication - I really enjoyed it.

Why is communication so important in science?

Perhaps they have always been there, but nowadays there seem to be more misconceptions around science that can lead to dangerous ideas, such as the anti-vaccine crusade. Better communication about science would give people an understanding, so that that they can hopefully appreciate the benefits of vaccines and other important interventions.

What has been your biggest learning curve so far?

I learn a lot from my outreach work with children - they are so smart. As you grow older you have more to lose, so you develop a sense of fear and stop asking important questions. I think they ask more probing questions than adults, and I find they inspire me to change my approach to my work.

A key element of understanding something is being able to explain it in simple terms. A good scientist should be able to explain their work to anyone.

Who inspires you?

I've been fortunate to have lots of great role models - male and female - but my parents are my biggest inspiration. They are both immigrants that have overcome their own share of challenges to build a life for my sister and me. Education was a privilege that they worked hard for so that we could have more opportunities than they did. Both are half Ghanaian, but my mum is half Lebanese and immigrated to the UK. My dad is half Dominican and immigrated to the Netherlands - which means that I am fortunate to have claim to five nationalities.

What gets you up in the morning?

In the world of science things don't always work the first time, but I love the feeling of carrying out an experiment and getting an unexpected result. Often that is where new discoveries are made.

What are you most proud of?

Honestly, I am just proud to be here. We often doubt ourselves, particularly if there aren't role models that look like us. But my advice to anyone considering a career in science is don't let that stop you. The only way you definitely won't get in is by not applying.

WATCH LAYAL EXPLAIN HER PHD IN THE PUB: