Features

Many local authorities can and should be doing more to help the young people they have looked after. Large numbers of care leavers (aged 18-25) report anxiety, loneliness, and lack of support, according to a long-term research project funded by the Hadley Trust and led by Oxford Professor of Education and Adoption, Julie Selwyn CBE, and Linda Briheim-Crookhall ( Coram Voice).

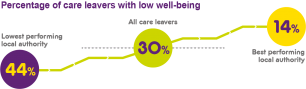

Among a host of appalling statistics, the most shocking finding in the recently published research on care leavers, is that the lives and futures of care leavers is genuinely determined by that over-used expression, a postcode lottery - see illustration 'percentage of care leavers with low well-being', below.

The lives and futures of care leavers is genuinely determined by that over-used expression, a postcode lottery

While care leavers in some areas report a positive experience and go to university alongside their peers, life for young people in other areas is horrifyingly different.

The report shows these Local Authorities are providing insufficient support with some young people feeling abandoned. Concerning, was the percentage (24%) of care leavers who recorded they had a disability or limiting long-term health problem: twice as many as their peers in the general population. This group of care leavers frequently reported feeling isolated and not having even one good friend. Many had high stress scores and 35% felt lonely always or often - see illustration immediately below for report findings.

A report on 11 Nov from the Children’s Commissioner, showing that young people in care are routinely being failed, accorded with the findings from the care leavers’ report.

Professor Selwyn says, ‘The variation in Local Authority can be stark. Nearly 80% of care leavers living in the best performing Local Authority area report that they feel safe but, in the lowest performing area, about half tell us they feel unsafe. They may be living in hostels, with adults who have problems of addiction and who are much older than them or living in a flat on their own.

‘But some young people feel that being in care has been a very positive experience. A quarter of care leavers in our surveys had very high well-being and many have gone to university. Some care leavers are here, at Oxford in our undergraduate, Masters and Doctoral programmes.’

In the lowest performing area, about half feel unsafe. They may be living in hostels, they may be living in hostels with adults who have problems of addiction and who are much older than them or living in a flat on their own....but some young people feel that being in care has been a very positive experience. A quarter had very high well-being

The report states, ‘There was an association between very high well-being and care leavers feeling that they had been treated the same or better than other young people. This suggests that services that actively seek to compensate for the additional challenges that their care leavers face are likely to help make their lives better.’

All this goes to show that young people leaving care can have good outcomes, but Professor Selwyn maintains the Local Authorities’ procedures are critical in making the difference.

Care leavers benefit from the Local Authorities’ policies in terms of housing and financial advice and support. Leaving care workers play an important and unsung role in helping young people transition to independent life. Care leavers also need to understand their histories but, surprisingly, 23% still did not have a full understanding of why they had been in care.

According to the report, ‘When the state steps in to look after a child, it is down to the state as their corporate parent, to step up to support care leavers to reach their full potential. Local authorities should want their children to do (at least) as well as other young people. When we compare how care leavers feel they are doing to other young adults, the difference is stark.’

Young people leaving care can have good outcomes, but Local Authorities’ procedures are critical in making the difference

Professor Julie Selwyn

The report shows that care leavers are much more likely to be struggling financially, with housing, or just with having someone they can trust compared with other young people. Care leavers with low well-being often felt afraid, they were more likely not to have a person in their life who listened, praised or believed they would be a success compared with other care leavers.

But the report insists, ‘Corporate parents should not accept that their care leavers do worse than other young people.’

And it recommends, ‘Address the continued postcode lottery by each local authority systematically measuring care leavers’ subjective well-being and identifying where their care leavers struggle and where they do better. Share the practices that promote positive experiences.’

Dr Selwyn’s report is based on 1,800 surveys of care leavers. Every Local Authority which takes part does so voluntarily and 50 out of 152 nationally have participated since 2017.

By David Macdonald, Director of WildCRU

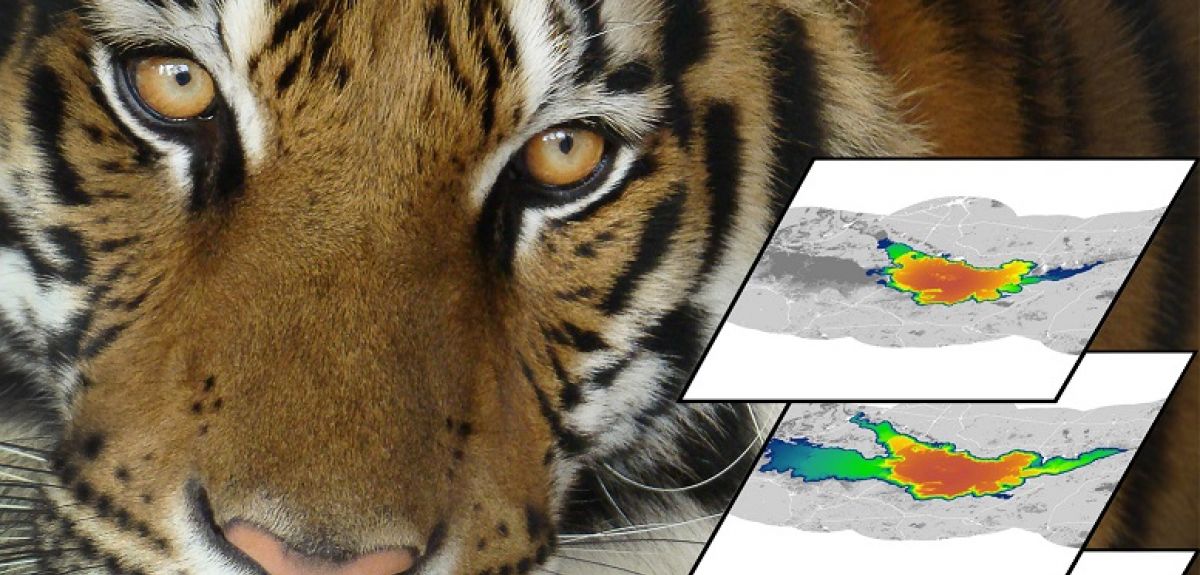

Tigers are in dire straits, with prospects for the Indochinese subspecies among the most dire of all. This is why I want to spotlight the work of Eric Ash for leading research on one of the few known breeding sites for the subspecies anywhere in the world.

Eric Ash, a doctoral student at Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU), part of the University of Oxford’s Department of Zoology, has dedicated himself to the conservation of tigers in Thailand for the last nine years. Now, with our collaborators at the Freeland Foundation, he has led our new paper published in the journal, Land.

The under-studied and endangered Indochinese tiger faces extinction and continuing declines, a distinction that unhappily makes the subspecies a candidate for Critically Endangered status

The under-studied and endangered Indochinese tiger (Panthera tigris corbetti) faces extinction and continuing declines, a distinction that unhappily makes the subspecies a candidate for Critically Endangered status. Thailand plays a crucial role in its conservation – there are few known breeding populations in other range countries. Our work has focused on Thailand’s Dong Phayayen-Khao Yai forest complex (DPKY), a group of five protected areas and UNESCO World Heritage Site, where Eric and Freeland Foundation, in partnership with the Thai-government and Panthera, conducted a massive camera-trapping study to find out just how the tigers there were faring.

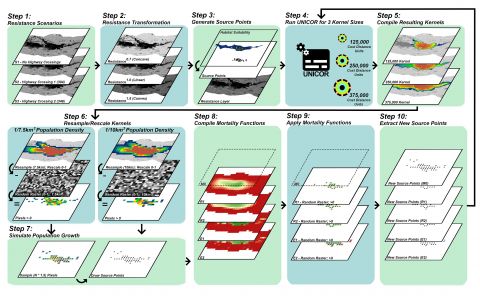

Importantly, we evaluate the sensitivity of population connectivity models to the variation and interaction of key factors, such as landscape resistance to movement, dispersal ability, population density, and mortality, over a series of timesteps. The article, led by researchers at WildCRU, offers insight into potential tiger range expansion scenarios.

The authors utilize spatially and temporally-dynamic simulations to model tiger population changes and dispersal from this landscape to potential habitat elsewhere in Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos, areas where tigers are thought to be extinct.Our new paper builds upon the remarkable news that this vital population of tigers could be recovering, as evidenced by signs that tigers are beginning to disperse from core areas into frontier habitat from which they had previously been extirpated

Our new paper builds upon the remarkable news that this vital population of tigers could be recovering, as evidenced by signs that tigers are beginning to disperse from core areas into frontier habitat from which they had previously been extirpated.

This was a huge analytical effort, informed by an even greater effort under arduous conditions in the field which generated over a million camera-trapping images and almost 80,000 collective trap nights over nine years. The team ran advanced analyses, requiring months of high-level computing, which produced 24,300 simulations of population, landscape connectivity, and density of dispersing individuals across the landscape to evaluate the effect of key factors.

The result? The computer models suggest that the tiger’s fate is extremely sensitive to variations in mortality and dispersal ability – and, over time, these two factors interact to strongly affect predictions. For the technical aficionado: incorporation of an explicit mortality component, reflecting differences in probability of survival across the landscape, combined with increased dispersal ability, resulted in considerably lower estimates of population and connectivity.

These results are hugely important for tigers, but they also offer an important lesson more broadly: given the importance of population connectivity modelling in cutting-edge ecological research, the approach of the WildCRU team can inform future assessments for rare or threatened species where empirical data are scarce – a challenge faced by many researchers around the world.

This study is among the first explicitly to evaluate the interaction of dispersal ability and mortality on population size, distribution and connectivity in a spatially and temporally explicit dynamic framework. The authors are convinced that future studies should adopt this approach, explicitly accounting for mortality risk across landscapes and potential interactions with dispersal ability over time. The ways in which these factors can vary over time in reality can drastically affect the simulated results. Importantly, for translating this research into impact, the study identified potential population growth and range expansion scenarios for tigers along with key factors relevant to their long-term management across this key landscape in Southeast Asia.

'How Important Are Resistance, Dispersal Ability, Population Density and Mortality in Temporally Dynamic Simulations of Population Connectivity? A Case Study of Tigers in Southeast Asia', Ash, E.; Cushman, S.A.; Macdonald, D.W.; Redford, T.; Kaszta, Ż. Land 2020, 9, 415. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/9/11/415

By Robin Dunbar, Emeritus Professor, Department of Experimental Psychology

Writing long novels is a pitfall for the unwary, as many an over-ambitious novelist has found to their cost. It’s very hard to maintain the reader’s interest even through 1000 pages of text, never mind keep this going over a series involving several books. Tolkien, of course, famously achieved it in the Lord of the Rings. And so has the American novelist and screenwriter, George R.R. Martin (once referred to as the American Tolkien) in A Song of Ice and Fire. As one of the most successful fantasy series of all time, it achieved iconic status when it was turned into the astonishingly successful TV series Game of Thrones. It has sold more than 90 million copies worldwide and has been translated into 47 languages.

Just consider the enormity of the task Martin set himself. In the five volumes published so far (we are still waiting for the promised sixth and concluding seventh), three separate main stories, with many subplots, are interwoven over the course of 343 chapters, more than 4000 pages and nearly two million words. There are more than 2000 characters who, between them, engage in over 41,000 interactions, with nearly 300 deaths – all crammed into the space of a mere handful of years of storytime. That’s more than enough to baffle and defeat even a Shakespeare – and Shakespeare was a master at tailoring his plays to suit the psychology of his audience.

The problem lies in the way the human mind has been designed by evolution to cope with the social world in which we typically live. That world is much smaller scale than most people realise. We can, for example, only hold four people in a conversation at the same time (and Shakespeare never breaks this rule onstage). Sixty percent of our social effort is devoted to just 15 core friends and family, and our entire personal social networks (the people we have meaningful relationships with) average just 150.

Yet, like Lord of the Rings, the Fire and Ice stories are gripping despite their size and have an enthusiastic international following. How did George Martin do it?

In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, a team of physicists, mathematicians and psychologists from Coventry, Warwick, Limerick, Cambridge and Oxford Universities have used network science methods to unpack the secrets behind A Song of Ice and Fire.

It turns out that Martin has very carefully mapped the structure of his storyline to fit the psychology of his readers in two crucial respects. First, the team found remarkable similarities to real life in the way the interactions between the characters are arranged. So much so, in fact, that the sprawling narrative neatly fits into the type of societies for which evolution has designed the human mind. Second, although important characters are famously killed off seemingly at random as the story unfolds, the underlying chronology is not at all unpredictable. Instead, Martin uses the literary device of making each of the chapters an integrated story and then randomly intermingling the stories out of chronological sequence.

Despite the enormous cast of characters and the fact that new characters are added at a constant rate in each of the 343 chapters, the typical number of active characters in each chapter is just 35, about the same as Shakespeare has in each of his plays (and, incidentally, the size that optimises research productivity for English language and literature departments in UK universities). The average number of contacts that each character within a chapter has is stable at between 12-16, about the same number that we would have in our close social circle (our so-called sympathy group).

Each chapter revolves around a central character who provides the “point of view” for the chapter. By virtue of their function as point-of-view characters, of course, these individuals necessarily interact widely, but none of the point-of-view characters has a complete network across the volumes that is significantly above 150. This is the same number as the average human personal social network, known as the Dunbar Number.

In other words, Martin keeps his characters’ networks within the limits that his readers’ human minds were designed by evolution to cope with.

While matching mathematical motifs might, in the hands of a lesser writer, easily have resulted in a rather narrow script, Martin keeps the tale bubbling along by making deaths appear random as the story unfolds, thereby maintaining the suspense for the reader. But, as the team show, when the true chronological sequence of the chapters is reconstructed, the deaths are not random at all: rather, they reflect exactly how non-violent human activities in the real world are typically spaced in time.

Game of Thrones has invited all sorts of comparisons to history and myth. In this respect, the social structure of Game of Thrones is more akin to historical texts that describe real events, such as the Icelandic family sagas, and quite unlike fictional mythological stories like Beowulf or the Irish Táin Bó Cúailnge. Giving the story the characteristic of real life ensures that it stays within the cognitive limits of the reader, thereby making it easier for the reader to track the story without becoming confused. The trick in Game of Thrones, it seems, has been to mix realism and unpredictability in a psychologically engaging manner.

As part of the Coventry University-based Maths Meets Myths Project, the marriage of science and humanities in this paper opens exciting new avenues for comparative literary studies. The computational power of network science has not yet been applied to humanities projects of this kind. Nonetheless, as this project demonstrates it offers the prospect of probing behind the tsunami of detail to provide novel insights into the patterns that underlie stories. As such, it offers a potentially valuable addition to the literary scholar’s analytical toolkit.

For the first time, researchers from Oxford’s Departments of Physics and Materials have managed to image hybrid metal halide perovskites with atomic-scale resolution providing new insights into these wonder-materials. A paper published in Science shares the groups’ findings about the materials’ remarkable self-healing powers; the findings further our critical understanding of how such perovskites work and are an essential step closer to the commercial production of perovskite solar cells.

Perovskites hold the promise of a new dawn for photovoltaic and optoelectronic applications – solar cells and light-emitting devices

Professor Laura Herz from Oxford’s Department of Physics and corresponding author, says: ‘Perovskites hold the promise of a new dawn for photovoltaic and optoelectronic applications – solar cells and light-emitting devices – but there is still much we need to know about them. We need to fundamentally understand these materials in order to fully harness their power. Up until now, researchers essentially had to guess how processing affected the material and so, in turn, the solar cell performance; our work will allow the field to directly determine how different fabrication routes affect the structure.’

Remarkably rapid recovery

The materials are very soft and therefore electron-beam sensitive however, using specialist electron microscopy imaging, the team were able to observe the perovskite structure at atomic resolution. They found that prolonged electron irradiation degraded the structure as expected but that an intermediate structure formed that allowed for the material’s rapid recovery. Further observations of the atomic arrangement within the hybrid perovskite films showed that small inclusions of lead iodide (which is used as an ingredient) form a surprisingly coherent transition boundary that nearly perfectly follows the surrounding perovskite structure and orientation. The observation suggests that lead iodide may seed perovskite growth and explains why an excess of lead iodide tends not to impede solar cell performance. Studying the material at this atomic level revealed essential information about the nature of the structure’s boundaries, defects and decomposition pathways.

Dr Mathias Rothmann, from Oxford’s Department of Physics and lead author, comments: ‘We have been able to study photoactive perovskite thin films with atomic resolution in their native thin-film state, which is what you find in a solar cell device. We were able to observe a range of different boundaries between the crystal domains in the film, which are very important for solar cell performance but not very well understood.

'We observed different types of defects that haven't been described for this material before, as well as the inclusion of a secondary material – all of which can potentially have a significant impact on the overall performance of the solar cells, but which are impossible to study without the level of resolution we have managed to get. This detailed level of understanding has been essential for the rise of silicon-based solar cells, and we can therefore only begin to imagine the impact it will have on the future of perovskite solar cells.’

Perovskites for commercial solar cells

Professor Herz concludes: ‘Our findings have revealed several, possibly unique, mechanisms that underpin the remarkable performance of this technologically important class of hybrid lead halide perovskites. The highly adaptive nature of the perovskite structure accounts for its exceptional regenerative properties and our atomic-resolution observations of interfaces within the material will contribute significantly to being able to eliminate defects and optimise interfaces. This is exactly the exciting kind of information we need to make perovskites ready for commercial solar cells.’

Read ‘Atomic-scale microstructure of metal halide perovskite’, in Science, Vol 370 Iss 6516.

COVID-19 hit England’s social care sector like an ‘earthquake’, according to Oxford Professor of Sociology and Social Policy, Mary Daly, and revealed a sector in crisis and a worrying attitude towards older and vulnerable people.

In a recent article, COVID‐19 and care homes in England: What happened and why?, Professor Daly maintains the treatment of care homes during the first months of the pandemic is ‘fast generating the sense of a scandal’. While the NHS was ‘front and centre of the national response’, Professor Daly says, ‘Care homes were poorly targeted and in many senses neglected until late in the pandemic when a response was unavoidable.’

In the report, Professor Daly exposes ‘erroneous policy choices’ and ‘many mistakes’. But, she says, the reasons for the crisis are ‘more complex’ and fundamental – a mixture of structural and politico/socio cultural factors.

In the report, Professor Daly exposes ‘erroneous policy choices’ and ‘many mistakes’. But, she says, the reasons for the crisis are ‘more complex’ and fundamental

Social care struggles to be seen as a priority, she says, exacerbated by the separation of social care and the health system which makes governance and supply routes difficult, especially in a pandemic. There have also been ‘years of austerity and resource cutting’ which have depleted the ability of local authorities to bolster social care.

In her report, Professor Daly directly criticises the long-term lack of political support for the sector and, in terms of COVID-19, the government’s calculation that care homes might be seen as less important than the NHS and, as a result, policy errors less likely to ‘hurt’ them than an NHS blunder. But, Professor Daly maintains, ‘The weak regulatory tradition of the sector also contributes to explaining the inadequacy of the response. Care homes and social care in general are far down the chain of public policy and the majority are market providers which see relatively little regulation.’

Care homes and social care in general are far down the chain of public policy and the majority are market providers which see relatively little regulation

There have been positives, she says, ‘Initiatives are coming forward to integrate health and social care.’

And, Professor Daly says, the Government did allocate some £600 million to the sector in mid-May and families, prevented from seeing their relatives, have mobilised and made themselves heard

But, talking to Arts blog about the crisis, Professor Daly says, ‘It has revealed fundamental flaws in the sector. There are the problems of funding but there is also the governance system [regulation] and inadequacies in homes.’

Professor Daly maintains, ‘Too few care homes are in the top tier. Very few are ‘Outstanding’ homes.’

Under the care regulation system, governed by the Care Quality Commission, homes are ranked as ‘Outstanding’, ‘Good’, ‘Requires Improvement’ and ‘Inadequate’. Currently, on this scale 4% of homes for older people in England are ‘Outstanding’, while more than 2,000 care homes, one in five, fall into the substandard categories. The system was intended to mirror the Ofsted system of school inspections, but some 20% of state secondary schools are currently ‘Outstanding’ with 14% substandard.

‘Social care is a very difficult area for any government. It is a political hot potato [and no government has wanted to deal with it],’ Professor Daly adds. ‘Care homes needed to be protected before Covid, it was a signal mistake.’

It worries me what all this says about our valuing of older and vulnerable people. I fear they are seen as acceptable casualties

But, she emphasises, ‘It worries me what all this says about our valuing of older and vulnerable people. I fear they are seen as acceptable casualties.’

Professor Daly warns that there is a problematic fault line within the sector, ‘Privatisation in care means that there is a very great reliance on market provision in social care...local authorities got out of provision and now care home owners are responsible for caring for our older and vulnerable people....when care is about profit we need to wake up.’

In concluding her report, Professor Daly calls for, ‘A new model of care for older adults. The large and diverse network of independent providers does not look like a resilient form of provision and is likely to have become even less resilient following the pandemic.

‘Ultimately, the country has to answer the question of what is an acceptable way of caring for its older people and view the pandemic outcome as associated not just with short‐term failures of policy and political leadership but a much deeper undervaluing of the came home sector, the activity of caring and those who require care.’

There is a very great reliance on market provision...care home owners are responsible for caring for our older and vulnerable people....when care is about profit we need to wake up

She insists, ‘Long‐term care policy has to become a meaningful part of the British welfare state in which the rights and entitlements of those involved are given a central place, unseating the far more dominant risk, exigency and need perspectives.’

- ‹ previous

- 29 of 247

- next ›

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences