Features

Concerns over missed education for young people have spread around the world with schools and colleges firmly shut for long stretches because of COVID-19. In England, the Government has announced large-scale funding to help education recover from the devastation of the pandemic. As part of this, the very youngest children, who have poor oral language skills and have been particularly affected by the switch to online learning, will be able to access specialised help – key to academic success.

It is widely recognised that language skills are fundamental to many aspects of cognitive and psychosocial development, and that poor language skills are a barrier to educational success.

The current rollout of the NELI programme in English primary schools is a stunning example of how basic academic research can be translated into practical application at large scale

Developed by an Oxford team, led by Professors Charles Hulme and Maggie Snowling, the Nuffield Early Language Intervention (NELI) programme improves oral language skills in young children. According to research by this group, there can be a transfer effect with oral language interventions, leading to improved reading comprehension.

As a result of official funding, it is hoped that all primary schools in England that want it, will benefit from the Oxford oral language programme. Last autumn, the Department for Education announced a £9 million investment in the programme, with a further £8 million announced for next academic year. In this academic year, this funding has enabled the programme to be delivered by some 6,500 schools. Schools wishing to register interest, can do so here.

The current rollout of the NELI programme in English primary schools is a stunning example of how basic academic research can be translated into practical application at large scale.

Children’s oral language skills are a critical foundation for the whole of formal education....Good language skills underlie a child’s ability to learn to read and to master arithmetic

Professor Charles Hulme

Professor Hulme says, ‘Children’s oral language skills are a critical foundation for the whole of formal education. To learn in the classroom, children need to understand what is said to them and be able to express their thoughts and feelings. Good language skills underlie a child’s ability to learn to read and to master arithmetic.’

Dr Gillian West, a member of the research team, comments, ‘Language skills are also critical for children’s social and emotional development, and their ability to make friends.’

Language skills can vary greatly among social groups. According to Professor Hulme, ‘It is well established that children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds often enter school with weak language skills. The NELI programme offers the potential to help reduce social inequalities in educational outcomes and can also be used effectively with children for whom English is an additional language.’

Language skills are also critical for children’s social and emotional development, and their ability to make friends

Dr Gillian West

The schools taking part identify five or six children in each reception class with the weakest oral language skills.

Last month, a study of NELI’s effects by Professor Hulme showed that the programme produced sizeable improvements in children’s language skills and small improvements in word reading skills.

Teachers and teaching assistants are trained to deliver the NELI programme using an online training programme, developed by the Oxford team, and delivered on the FutureLearn platform. The schools taking part identify five or six children in each reception class with the weakest oral language skills.

These children receive the programme get two 30 minute group sessions each week and three 20 minute individual sessions. During these periods, the children are involved in speaking and listening activities including storytelling and learning new words. Once staff are trained, NELI can be implemented in schools year after year, benefitting generations of children.

Identifying those children who would benefit from the programme is key. Teachers need a way to identify language weaknesses when using the NELI programme. A ‘LanguageScreen’ assessment app has been developed by Professor Hulme’s research group in collaboration with Dr Mihaela Duta and Dr Abhishek Dasgupta in Oxford’s Department of Computer Science. It is now available to all schools via an Oxford spinout company (LanguageScreen.com).

Dr Duta says, ‘It is a great pleasure to bring software engineering to bear on an issue of such social importance.’

Children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds often enter school with weak language skills. The NELI programme offers the potential to help reduce social inequalities in educational outcomes and can also be used effectively with children for whom English is an additional language

Professor Hulme

The Education Endowment Foundation, with private equity enterprise ICG, provided funding to develop online training for the programme, ensuring it could be offered in a social-distanced manner as well as at national scale.

LanguageScreen runs on a tablet or phone and gives teachers an accurate and rapid assessment of a child’s language ability via a secure automated online report. LanguageScreen will allow teachers to monitor the development of children’s language skills.

By Dr Ellie Bath, Department of Zoology

Mating changes female behaviour across a wide range of animals, with these changes induced by components of the male ejaculate, such as sperm and seminal fluid proteins. However, males can vary significantly in their ejaculates, due to factors such as age, mating history, or feeding status. This male variation may therefore lead to variation in the strength of responses males can stimulate in females.

Using the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, we tested whether age, mating history, and feeding status shape an important, but understudied, post-mating response – increased female-female aggression.

Two females fighting over food

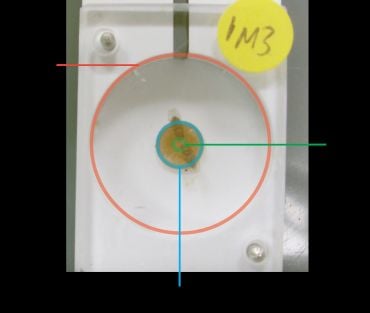

Two females fighting over foodImage 1: Two female fruit flies are standing on a food cap (which contains food that they eat and lay eggs in). This is where the majority of fighting happens – you can see the flies have their legs touching, so they are probably fencing in this image. Each fly is marked with a different colour of paint to aid identification.

We found that females mated to old males fought less than females mated to young males. Females mated to old, sexually active males fought even less than those mated to males who were merely old, but there was no effect of male starvation status on mating-induced female aggression.

Male condition can therefore influence how females interact with each other – who you mate with changes your interactions with members of the same sex!

Image 2: This figure shows the setup we used for contests between females, which consisted of a circular arena with a food cap set into the middle. This food cap contained regular fly food medium, with a drop of yeast paste in the middle to act as a valuable, restricted resource.

Contest arena setup

Contest arena setupCould this happen in other species?

We know that other species (including humans!) have proteins in the seminal fluid that males transfer to females during sex. Various of these proteins have effects on female physiology and behaviour, but no one knows if these affect aggression (in humans or any other species).

We also know that male age (in flies and humans) results in reduced fertility and can have serious effects on their offspring. Although it is a long leap from flies to humans, could who you mate with influence your interactions with other females?

Many reproductive molecules and important bodily functions are conserved across the animal kingdom from flies to humans, so it is possible that what we found in flies here might be hinting to a common phenomenon across the tree of life. We need more studies to understand if this is the case!

Read the full paper, 'Male condition influences female post mating aggression and feeding in Drosophila' in Functional Ecology.

By Professor Jane McKeating, Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine

Oxygen is essential to all life forms, even viruses.

Oxygen is fundamental to all cells, impacting key functions such as metabolism and growth. Our cellular response to oxygen levels is tightly regulated and one important pathway is controlled by the Hypoxia Inducible Factors (HIFs), that activate certain genes under low oxygen conditions (hypoxia) to promote cell survival. Drugs that activate HIF are currently in use to treat anaemia caused by kidney disease.

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 needs no introduction and literally stopped the world in 2020, with more than 2 million fatalities to date. A defining feature of severe COVID-19 disease is low oxygen levels throughout the body, which may lead to organ failure and death. A cure for this virus is urgently needed.

Dr Peter Wing and Dr Tom Keeley, working in the laboratories of Prof Jane McKeating, Prof Peter Ratcliffe and Dr Tammie Bishop in the Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, discovered that a low oxygen environment supressed SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells that line the lungs and reduced viral propagation and shedding.

Importantly, drugs that activate HIF such as Roxadustat had a similar effect on the virus. This study provides the first evidence for repurposing HIF mimetics that could reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission and disease development. The oxygen dependency of this virus is a new vulnerability that we could exploit.

Research continues to expand our understanding of the interplay between oxygen sensing and COVID-19 and is published in Cell Reports.

By Talitha Smith, Communications Officer, Department of Physiology Anatomy and Genetics (DPAG)

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a bulging of the aorta, the body’s main blood vessel, which runs from the heart down through the chest and stomach. Prevalence of AAA in the population is high, up to nearly 13% depending on age group, particularly for men aged 65 and over. An AAA can get bigger over time and rupture, causing life-threatening bleeding. There is a high mortality rate of around 80% in patients with ruptured AAA; only dropping to around 50% when patients undergo surgery.

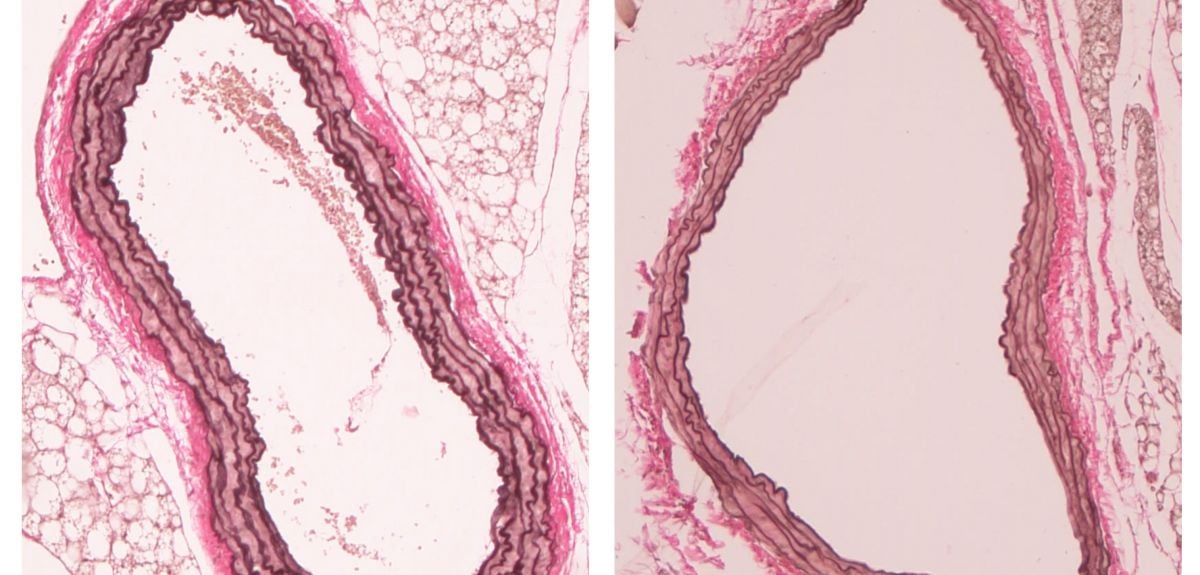

Comparing a healthy aorta with what it looks like in the event of an aneurysm

Comparing a healthy aorta with what it looks like in the event of an aneurysmScientists know that in some patients there is a genetic predisposition to AAA, and large genomic studies have identified that mutations in a large protein called LRP1 predispose people to aortic aneurysm, as well as other major vascular diseases. However, the mechanism responsible for how these mutated genes cause the disease has so far been unknown.

Vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation is essential to the development of healthy blood vessels. The smooth muscle cells of the aorta play a crucial role in maintaining its stability and protecting it against disease. In their healthy contractile state, they provide strength and produce the elastin proteins to withstand forces and assist with pumping blood around the body. In disease, damage to the lining of the aorta causes accumulation of fat and allows immune cells to infiltrate vessel walls. In response, the vessel attempts to repair itself and the smooth muscle cells try to make more smooth muscle. However, in doing so, the cells start to de-differentiate and become less contractile.

They undergo proliferation, presumably with good intentions to try and make more smooth muscle, but actually it makes the problem worse.

According to Associate Professor of Cardiovascular Development and Regeneration Nicola Smart: 'They undergo proliferation, presumably with good intentions to try and make more smooth muscle, but actually it makes the problem worse. In doing so, they also break down the elastic layers that keep the vessels stable. These layers are supposed to hold the whole vessel together, keep it tight and keep it strong, and it all breaks apart.'

But why do the smooth muscle cells react in this way? Professor Smart's research group has found that a small protein called Thymosin b4 (Tb4) is working alongside the larger LRP1 protein to determine how many 'growth factor receptors' are sent to the cell's surface to respond to disease. If Tb4 is absent, then instead of being destroyed, too many receptors are recycled back to the cell's surface, which makes the smooth muscle cells hyper-sensitive and in essence overreact.

Professor Smart’s team then compared their results with AAA samples from the Oxford Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm study. The OxAAA team surgically repair aneurysms in human patients, removing diseased tissue from the lining of the abdomen in the process. Through examining these samples, the Smart group were able to confirm that Tb4 and LRP1 interact in both healthy and diseased patient vessels. Consequently, their study sheds light on a key regulatory step in AAA and Tb4 has been identified as a promising new drug target to potentially treat the disease.

More details can be found in The Journal of Clinical Investigation, (which includes a full list of contributors, including the first author, DPhil student Sonali Munshaw).

Lockdown learning, with school delivered online, may not be ideal, but it has enabled some highly-unusual lessons to take place. Oxford Classics professors have taken to the internet to engage in ‘Classical Conversations’ with school pupils across the country and the results have excited interest – in all concerned.

The Faculty of Classics Outreach Team has been offering 30 minute classes with an Oxford professor on a Classical subject of the school’s choice – or just a quick-fire question and answer session. And the response was almost immediate – once schools were convinced this offer was ‘for real’. In the last three months, some 600 children at 30 schools from Lancashire to Kent, Norfolk to Wiltshire have taken part. And many more conversations are scheduled over the coming months.

Oxford Classics professors have taken to the internet to engage in ‘Classical Conversations’ with school pupils across the country and the results have excited interest – in all concerned

According to Dr Neil McLynn, head of Classics, the idea was to use the virtual learning of lockdown to ‘zoom' into lessons, in the nicest possible way, giving students a chance to have a conversation with an Oxford expert about their favourite subjects. And, he says, the Faculty has been thrilled.

The project matches primary and secondary school and home-educated students with leading Oxford academics. Topics have ranged from ‘Female characters in the Odyssey’ to ‘Magic and Superstition in Rome’.

But some have been less prosaic, Dr Sophie Bocksberger took part in a Q&A session with a group of primary-aged children. She recalls there were some challenging questions, ‘One boy asked about the toilets in Ancient Greece [he thought everyone would want to know]...somebody else asked if the Greeks had pets and someone asked which was the best god.’

Although such questions would not normally feature in a university Classics course, ‘it was really amazing’, she says. ‘They were really curious about daily life in Ancient Greece and it worked well. I tried to show how we know things, through archaeology or texts, rather than just giving answers.’

One boy asked about the toilets in Ancient Greece...somebody else asked if the Greeks had pets and someone asked which was the best god

Dr Sophie Bocksberger

[In case of interest, toilets were receptacles, emptied into the street, although wealthier Greeks may have sat on marble benches.]

Students, meanwhile, have found the sessions ‘awesome’, ‘really engaging’, ‘very enjoyable’ and ‘fun’, according to their teachers. Many commented that, getting to share their ideas and talk with an Oxford Classicist has, not only, helped them in their current academic work, but has also helped to prepare for the future by giving them an idea of what further classical study might be like.

Dr McLynn also faced a ‘free fire’ round of questions on any subject, but with secondary school pupils. He says, ‘They were full of interest in the Roman world.’

Questions included: who wore togas, farming and food in the UK during Roman times.

‘It was so interesting,’ he says.

A key aim has been to encourage and enthuse school children about the Classics and, the teachers insist, it has been effective

Dr Arlene Holmes-Henderson

Some Classical Conversations have centred on the GCSE or A Level syllabuses, with academics sharing their knowledge on topics such as Greek Tragedy, the Parthenon, and the Julio-Claudian Emperors. Others have delved into topics as varied as ‘Persuasive Language in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar’, life in Ancient Egypt, and ‘Feathered Creatures in Mythology’.

In another lesson, Dr McLynn met a group of sixth form Latinists who were studying Juvenal.

‘It involved some very hard questions,’ he remembers.

The project has been received with considerable enthusiasm and imagination in schools and in the university, where the Faculty is keen to encourage applications from a wide variety of applicants – even those without experience of Classics.

One Q&A, involving Professor Peter Stewart and a group of Classical Civilisation students, took place in a virtual ancient theatre. And Professor Armand D’Angour chatted with a class of secondary students about Ancient Greek music.

Dr Gail Trimble, meanwhile, says, ‘It has been really effective...the students have a chance to talk about the subject in a broader way and, for me, joining a lesson without being a ‘visitor’ in a school, having to be looked after, has meant schools got more out of it.’

They talked about heroism and the Roman political context – giving students a taste of what Classics at university might be like

Dr Gail Trimble

She spoke with a group of year 12s, who are studying Virgil’s Aeneid, and they had some ‘very bright questions’. She says, rather than looking narrowly at the text as though it were an A level lesson, they talked about heroism and the Roman political context – giving students a taste of what Classics at university might be like.

Schools too are very positive. According to one school, it was ‘very much a conversation – we could ask questions and input our own ideas whilst being guided and taught’, which meant that ‘the conversation was open to lots of different avenues and interpretations.’

Meanwhile, a teacher says, our Oxford expert ‘answered all questions with humour and intelligence and the students really loved it. I think they also loved having an expert in the field.’

Dr Arlene Holmes-Henderson, Research Fellow in Classics Education, says. ‘These 30-minute sessions offer students different viewpoints and ideas to enrich their knowledge and enjoyment of the topic. They might add detail or draw links between different parts of the literature, art and history which they find interesting.’

A key aim of the project has been to encourage and enthuse school children about the Classics and, the teachers insist, it has been effective. The potential for sparking interest is what energises the Classics team.

During school years, there can be moments of direct personal contact with people outside of school which can be transformative

Dr Neil McLynn

Dr McLynn maintains, ‘During school years, there can be moments of direct personal contact with people outside of school which can be transformative.‘

You can find out more about the project here https://clasoutreach.web.ox.ac.uk/classical-conversations.

If teachers would like to request a Classical Conversation, please email [email protected]. Preference will be given to state-maintained schools but we welcome requests from all teachers.

- ‹ previous

- 22 of 247

- next ›

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences