Features

Dozens of humanities academics will be taking part in a major public engagement event called FRIGHTFriday tonight (25 November). The event is a collaboration between The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH) and the Ashmolean Museum.

In a guest post, TORCH Director Professor Elleke Boehmer tells us a little more about what will be happening, and why this is part of TORCH's creative strategy to get a wide audience to engage with humanities research.

'It is easy to get people interested in research into a new life-saving drug, or a discovery that birds can use tools to get food. But for us arts and humanities researchers, it is sometimes harder to engage the public with what we do.

So here at The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH), we have set out to demonstrate the dynamic and impactful ways in which we work by organising an evening event at Oxford's the Ashmolean Museum this Friday (25th November).

Thousands of people are expected to attend the event, called FRIGHTFriday, and in some ways it will be a typical night out: there will be music, dancing, and a bar. But visitors will also be mingling with dozens of humanities academics, who will explain their research in some very creative and often unusual and challenging ways.

One of the stars of the show will be historian Professor Steven Gunn, who studies coroners' reports of accidental deaths in Tudor England. He will be hosting a game show, in which he sets the scene for deaths that really happened in Tudor England and asks teams of visitors to guess what happened next. From killing by bacon to death by books we learn how precarious life was in this period, and how people coped with extreme events.

English literature expert Professor Sally Shuttleworth leads a research project called Diseases of Modern Life. To engage people with her research, she will be talking about the various phobias she has discovered in Early Modern England, including a fear of cats, phobias that continue to this day.

Crime writer Margie Orford will explore the attraction of the dead white woman in western art. While music researcher Leah Broad is leading drama pieces from the Swedish playwright Strindberg where the actor answers a series of phone calls and the audience only hears half the eerie conversation. Again we develop a very real sense of the fundamental fears that drive what we do.

As you can imagine, our academics are leaving their 'comfort zone' of lecture halls and classrooms far behind on FRIGHTFriday, while at the same time demonstrating the inventive and creative thinking that is involved in all their research.

Working with other arts organisations and cultural institutions, like the Ashmolean Museum, allows humanities scholars to reach a large, new audience with their research. This kind of knowledge exchange has been a major focus of recent TORCH projects.

We have historians using their research to help the National Trust refresh their visitor materials. At FRIGHTFriday, there will be a theatrical performance which has come from a collaboration between the University of Oxford, a youth theatre in East Oxford, and the Fondazione Cini in Venice.

It is also important for us to look to apply our expertise beyond the world of culture and the arts. Recent projects have brought together humanities academics and scientists, and collaboration has deepened both groups' understanding of the questions they are working on.

Oxford theologians and philosophers are working with healthcare professionals on the importance of compassion in the health system. A collaboration between TORCH and the eating disorders charity Beat has investigated how fiction affects and is affected by readers' mental health.

The humanities disciplines have so much to offer to society and, here at TORCH, we will continue to facilitate connections between our academics and people from all backgrounds and all disciplines.

That might mean advising NHS commissioners, or entertaining revellers on a Friday night at the Ashmolean Museum.

FRIGHTFriday is a collaboration between TORCH and the Ashmolean Museum, with support from the Wellcome Trust. It is the national Festival Finale for the Being Human Festival.'

Professor Nicole Grobert, a nanomaterials scientist at Oxford University, has been awarded a Royal Society Industry Fellowship to work with Williams Advanced Engineering, part of the Williams group of companies that includes the Williams Martini Racing Formula One team. In doing so, she has become the first person to hold all three of the Royal Society’s Industry, University Research and the Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowships.

As part of her new industrial fellowship, Professor Grobert will support Williams Advanced Engineering's Technology Ventures Group to help bring emerging nanomaterials technologies and IP to market.

Nanomaterials, which exist in a range of different shapes and include the 'supermaterial' graphene, are so tiny that modern techniques such as advanced electron microscopy are required to see them. By definition, all nanomaterials are no bigger than 100 nanometres (100 billionths of a metre) in at least one direction.

Professor Grobert, who heads the Nanomaterials by Design Group in Oxford's Department of Materials, said: 'This Royal Society Industry Fellowship provides an excellent opportunity to bridge the gap between research and industry and help accelerate the commercialisation of this rapidly developing area of science. My group has already been working on a number of nanomaterial-application engineering projects with Williams, funded by Oxford's EPSRC Impact Acceleration Account, and I look forward to more innovation projects with Williams and the wider industry under this fellowship.'

She added: 'Nanomaterials is a hugely exciting field in which the possibilities are limitless. In theory, nanomaterials can outperform traditional materials. They can be highly conductive, lightweight and ultra-strong. If we tackle current practical challenges related to manufacturing, characterisation, processing and handling, nanomaterials could be the answer to many of modern society’s problems, including the ever-increasing demand for better energy and healthcare solutions.

'Williams Advanced Engineering inspired me to apply for this fellowship with their vision of delivering performance-engineered solutions that make a positive societal impact. Identified as one of the "eight GREAT technology areas" by the UK government, advanced materials combine both our science and business strengths, with UK material-related industries having a yearly turnover of £197 billion.

'Key to the success of nanomaterials is a multi-pronged approach – designing new, controlled production routes, combined with novel nano and classical materials, with end-user applications in mind. The Royal Society Industry Fellowship will enable this. In a few decades, nanostructured materials could easily exceed the importance that plastics have in our lives today.'

After completing her PhD, Professor Grobert joined Oxford and was awarded a Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship, followed by a Royal Society University Fellowship and an ERC Starting Grant. This long-term funding was crucial in helping Professor Grobert and other scientists at Oxford towards the challenging goal of taking blue-skies research to the next level by achieving the controlled production of new carbon and non-carbon-based nanomaterials – in particular, the structural control of nanomaterials down to the atomic level.

Craig Wilson, Managing Director of Williams Advanced Engineering, said: 'Williams Advanced Engineering is extremely excited about Nicole joining our team of experienced engineers, and being able to continue to offer her deep knowledge of materials science across our programmes and ventures to help ensure we can deliver state-of-the-art technology solutions.'

Professor Patrick Grant, Head of the Department of Materials at Oxford, added: 'With our strong history of collaboration with world-leading industries, we are delighted to participate in this Royal Society Industry Fellowship that will allow us to strengthen further our links with Williams Advanced Engineering. Through her earlier Royal Society-funded Dorothy Hodgkin and University Research Fellowships, Professor Grobert has generated the fundamental knowledge and facilities that allow large-scale, controlled manufacturing of nanomaterials in her laboratory. We are now looking forward to seeing the next generation of nanomaterials, designed at the Department, being incorporated in advanced engineering applications.'

In a guest blog, Professor David Roberts from the Nuffield Division of Clinical Laboratory Sciences at Oxford University explains the role of non-DNA genetic information in disease and development.

One of the great mysteries in biology is how the many different cell types that make up our bodies are derived from a single cell and from one DNA sequence, or genome. We have learned a lot from studying the human genome, but have only partially uncovered the processes underlying cell determination and susceptibility to different diseases.

The differences in the number of cells and their function between people are partly dependent on the genetic variation in the DNA code. The identity of each cell type is largely defined by an instructive layer of molecular annotations on top of the genome – the epigenome – which acts as a blueprint, unique to each cell type and developmental stage. Unlike the genome, the epigenome is modified as cells develop and in response to changes in the environment.

We have helped compile a landmark global study to characterise the role of not only intrinsic genetic variants, but also epigenetic molecular tags that decorate our DNA code, in the formation of blood cells. The research, published as part of a suite of articles, delves into these genetic variations in blood cells and how they influence common diseases such as arthritis.

Defects in the factors that read, write and erase the epigenetic blueprint are involved in many diseases. Comprehensive analysis of the role of genetic variation, combined with the knowledge of the epigenomes of healthy and abnormal cells, will facilitate new ways to diagnose and treat various diseases, and ultimately lead to improved health outcomes.

Our team at National Health Service Blood and Transplant at the University of Oxford, collaborated with researchers at the University of Cambridge and the Sanger Institute to conduct an in-depth study of blood cell genetic profiles in more than 150,000 people. We integrated genetic and epigenetic information to define more than 2,500 previously undiscovered associations of genome regions with blood cell characteristics and functions.

This study has increased the number of known genetic variants associated with blood cell types tenfold – creating the potential to develop new treatments for blood cell diseases, auto-immune diseases and arthritis. For example, we have found strong associations with the epigenetic markers of the turnover of red blood cells (or high reticulocyte counts) and cardiovascular disease, as well as associations of genetic markers of the eosinophil white blood cell numbers and rheumatoid arthritis. Here, the study has opened up new or overlooked pathways and mechanisms that lie behind these major diseases.

Our paper is one of a suite of 41 coordinated papers published by scientists from across the International Human Epigenome Consortium (IHEC), shedding light on these processes and taking global research in the field of genomics and epigenomics a major step forward.

The full research paper can be read in Cell, and the complete collection of papers from the consortium can be read here (volume 1) and here (volume 2).

Researchers in Oxford's Department of Computer Science are developing software to tackle the tricky business of lip-reading. With even the best human lip-readers limited in their ability to accurately recognise speech, artificial intelligence and machine learning could hold the key to cracking this problem.

While the new software, known as LipNet, is still in the early stages of development, it has shown great potential, achieving a performance of 93% against an existing lip-reading dataset.

Yannis Assael, a DPhil candidate in Oxford's Department of Computer Science who worked on the project, said: 'LipNet aims to help those who are hard of hearing. Combined with a state-of-the-art speech model, it has the potential to revolutionise speech recognition.

'The implications for the future could be quite significant. As we said in our LipNet paper's introduction, machine lip-readers have enormous practical potential, with applications in improved hearing aids, silent dictation in public spaces, covert conversations, speech recognition in noisy environments, biometric identification, and silent-movie processing.

'So far, we have compared the 93% performance of LipNet against human lip-reading experts – 52% – using the largest publicly available sentence-level lip-reading dataset, called the GRID corpus. LipNet also outperforms the best previous automatic lip-reading system, which achieved 80% on this dataset. And that system, unlike LipNet, predicts only words, not complete sentences.'

Brendan Shillingford, another Computer Science doctoral candidate who worked on the project, added: 'The GRID corpus has a fixed grammar and limited vocabulary, which is why LipNet performs so well there. Nonetheless, there are no signs that LipNet wouldn't perform well when trained on larger amounts of more varied data, and this is what we are working on now.

'In the future, we hope to test LipNet in a real-world setting, and we believe that extending our results to a large dataset with greater variation will be an important step in this direction.'

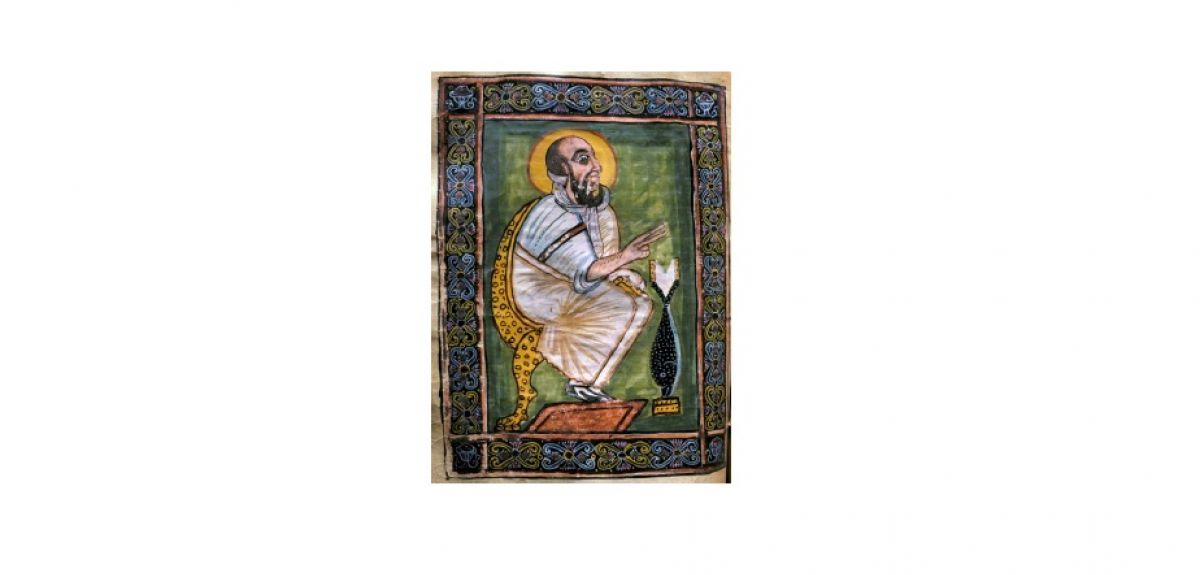

The Gospels of Abba Garima were hidden for centuries in Abba Garima Monastery in the Ethiopian highlands. According to tradition, God miraculously stopped the sun in the sky to allow Saint Abba Garima to complete them in a single day.

Now, for the first time, a photographic exhibition in Oxford is displaying the illuminated pages of the books.

‘These are amongst the earliest and most important of the rare illustrated gospel books to have survived from antiquity,’ says Oxford University’s Judith McKenzie of the Classics Faculty and the Faculty of Oriental Studies.

‘They are the earliest testament of the lost art of the Christian Aksumite kingdom of Ethiopia, which flourished around AD 350–650. Their vivid, finely painted illuminations are at once familiar but also entirely exotic, combining Ethiopian features with those seen elsewhere in Christendom. They include the earliest surviving set of portraits of the evangelists as frontispieces to their respective gospels.’

The exhibition coincides with the publication of a book about the gospels, ‘The Garima Gospels: Early Illuminated Gospel Books from Ethiopia’, which was co-authored by Judith McKenzie, with Francis Watson (Durham University).

The exhibition has been sponsored by the Classics Faculty, the Oxford Centre for Byzantine Research, and the ERC Advanced Project, ‘Monumental Art of the Christian and Early Islamic East’, directed by Judith McKenzie.

It was organised by Judith McKenzie, Miranda Williams, and Foteini Spingou (all from Oxford’s Classics Faculty) with photographs by Michael Gervers (University of Toronto)’ photographs.

It can be viewed from 9am to 5pm Monday to Friday, and 11am to 3pm on weekends, in the Outreach Room in the Ioannou Centre for Classical and Byzantine Studies on St Giles’, Oxford, OX1 3LU. Admission is free and the exhibition’s last day is Friday 28 July 2017. Groups can be booked for private viewings until Easter - please phone 01865 610236 or email [email protected].

- ‹ previous

- 105 of 247

- next ›

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences