Features

A gallery of potraits of great Oxford classicists has been installed at the University's Ioannou Centre for Classical and Byzantine Studies.

The portraits, which include Dame Averil Cameron, Gilbert Murray, Anna Morpugo Davies and Sir Fergus Millar, can now be viewed by members of the public in the building on St Giles' in Oxford.

There are images of 32 classicists in total - 28 are photographs and four are oil paintings.

‘These portraits, along with the current exhibition of the Garima Gospels, are part of our aim to brighten up the Classics Faculty’s building and invite people in to look around,’ says Mai Musié of the Classics Faculty.

‘The gallery not only provides a history of Classics at Oxford, but it also celebrates the contributions of many female classical scholars whose work has often not been fully recognised outside their areas of specialism,’ says Professor Fiona Macintosh, Curator of the Ioannou Centre.

A new role has been discovered for a well-known piece of cellular machinery, which could revolutionise the way we understand how tissue is constructed and remodelled within the body.

Lysosomes are small, enzyme-filled sacks found within cells, which break down old cell components and unwanted molecules.

Their potent mixture of destructive enzymes also makes them important in protecting cells against pathogens such as viruses by degrading cell intruders.

However, new research from the University of Oxford has revealed that in addition to breaking down cellular components, lysosomes are also important in building cellular structures.

‘We’ve traditionally viewed lysosomes as the cell ‘dustbin', because everything that goes into them gets chewed up by enzymes,’ said Professor Nigel Emptage from the University’s Department of Pharmacology, who led the research. ‘However, our research has revealed that lysosomes actually play a far more elaborate role, being involved in building as well as demolition, and playing a key part in structural remodelling of cells.'

The discovery was made while the team was looking at hippocampal pyramidal neurones – specialist brain cells important in spatial navigation and memory, which degenerate in Alzheimer's disease. The researchers observed that lysosomes were involved in supporting the growth of spines from dendrites, structures that increase the cell’s ability to store and process large amounts of information.

He added: ‘This discovery fundamentally changes how we view this well-known organelle, as it appears that without them new memory could not be stored in the brain. There has been a growing body of evidence for some time that lysosomes have other functions in addition to their traditional role, but it appears that they are also important in cellular construction.’

The full paper, ‘Activity-Dependent Exocytosis of Lysosomes Regulates the Structural Plasticity of Dendritic Spines’ can be read in the journal Neuron.

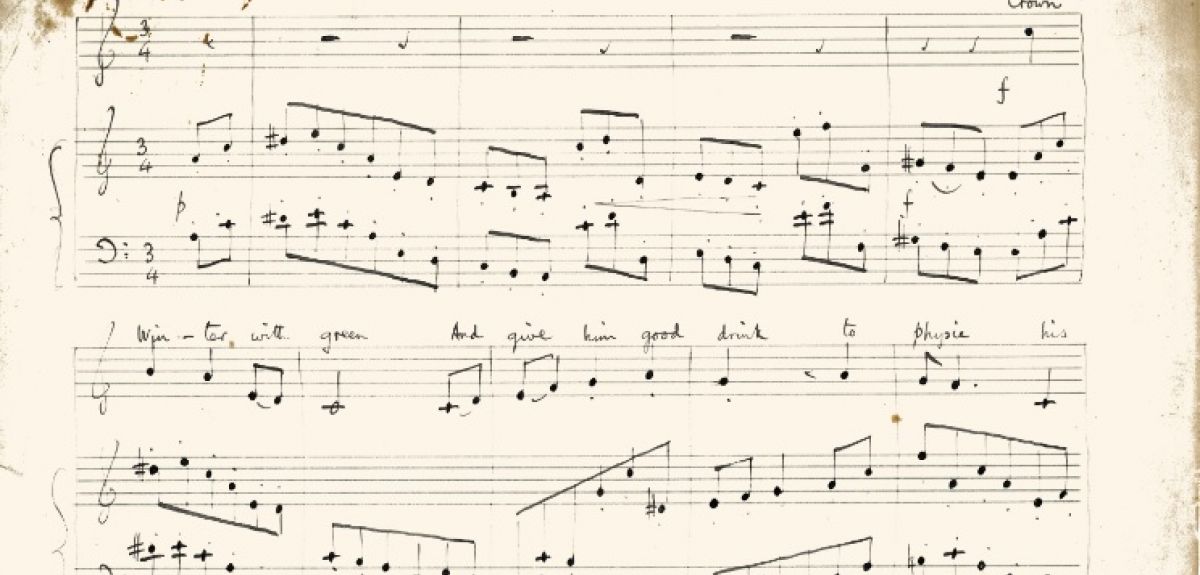

A long-lost song by English composer George Butterworth has been rediscovered at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries, a century after his death in the trenches.

The three-page score is a musical setting of a short festive poem by Robert Bridges, beginning with the words Crown winter with green. It is believed to be the only surviving copy of this Butterworth composition.

It was found among a group of uncatalogued music manuscripts which were transferred from the library in Oxford University's Music Faculty to the Bodleian's Weston Library.

The festive find is particularly special because the body of Butterworth’s surviving work is relatively small. Butterworth (1885-1916) was one of the most promising English composers of his generation, but his life was cut short when, at the age of 31, he was killed at the Battle of the Somme in World War I.

Before going off to war he destroyed all of his music which he thought not worthy of preserving. His few surviving works, which include his song settings of AE Housman’s poems from A Shropshire Lad and an orchestral idyll The Banks of Green Willow, are considered masterpieces.

The newly-discovered song has three verses and the lyrics speak of Christmas cheer. It begins with the words ‘Crown winter with green, And give him good drink To physic his spleen …’ and ends with the lines ‘And merry be we This good Yuletide.’ Butterworth’s later music often drew inspiration from English folk music and traditions. He wrote the musical setting for this poem in the style of a drinking song, for voice and piano.

It is not known how the manuscript came to be in the Bodleian Libraries. One possibility is that Butterworth’s father, Sir Alexander Kaye Butterworth, may have passed it on to Sir Hugh Allen, who was a great friend of the composer from his days as an undergraduate at the University of Oxford. Allen was Heather Professor of Music at Oxford from 1918 until his death in 1946, after which his collection of books and music was incorporated into the University’s Music Faculty Library, which is now part of the Bodleian Libraries. It is possible that the song was among these papers but its significance was not noticed at the time.

‘The song’s musical and technical shortcomings suggest that it is probably one of Butterworth’s earlier pieces, possibly dating from his school or student days, which would have been in the early years of the 20th century,’ said Martin Holmes, Alfred Brendel Curator of Music, who rediscovered the manuscript at the Bodleian.

‘As a song, Crown winter with green may not be a masterpiece, in the way that Butterworth’s later Housman songs undoubtedly are, but it can perhaps be seen as a small step on the path towards his musical maturity.'

The manuscript score of Butterworth’s Crown Winter with Green will be on public display in the Bodleian’s Weston Library from Wednesday 14 December to Sunday 18 December, 10am – 5pm (11am-5pm on Sunday). The display will be accompanied by a listening post where visitors can hear a recording of the song.

In a guest blog, Prof Paul Newton of the Nuffield Department of Medicine, and Head of the Medicine Quality Group at the Infectious Diseases Data Observatory (IDDO), explains the history of falsified medicines and highlights what needs to be done to avert a problem that threatens us all.

From Vienna to the Democratic Republic of Congo, fake medicines have threatened citizens across the board – and borders – in wartime as well as peacetime.

Falsified medicines have sadly probably been with us since the first manufacture of medicines and their producers may be the world’s third oldest profession after prostitution and spying. Last year falsified ampicillin was discovered circulating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in bottles of 1,000 capsules and containing no detectable ampicillin.

The post Second World War trade of fake penicillin inspired The Third Man, a fascinating film written by Graham Greene and set in Vienna. Many of the characters, including the protagonist, fake penicillin smuggler Harry Lime, were inspired by real spies and criminals who used penicillin – both falsified and genuine – to bribe, lure and get rich in the chaos of post-war Germany and Austria. Greene later turned the script into a novel.

Unfortunately, the problem is not yet consigned to history. There are probably thousands of Third Men hidden in today’s world, for example, a Parisian who ‘manufactured’ falsified antimalarials containing laxatives, international trade in falsified medicines especially from Asia into Africa, and emergency contraceptives containing antimalarials in South America.

But falsification is not the only problem. There are also severe issues with substandard medicines, poor quality medicines produced due to negligence, sometimes gross, in the manufacturing processes, but not deliberately to defraud patients and health systems. Their consequences are also very harmful; they are likely to be under-recognised drivers of antimicrobial resistance, as they often contain less than the stated amount of active ingredient.

For both falsified and substandard medicines objective prevalence data are few and poor quality, as there has been remarkably little research or surveillance. The data are insufficient to reliably estimate the extent of the problem. Much more investment is needed to understand the epidemiology of poor quality medicines and guide interventions.

Considered a ‘miracle’ medicine, penicillin was highly effective to treat gonorrhoea and syphilis, common venereal diseases among soldiers. During the Second World War and shortly after, the drug supply was controlled by the authorities and primarily reserved for the Army, but as often happens with prohibitions, the illegal trade flourished.

Penicillin was so scarce but so sought after, as an innovative cure of many important bacterial infections, that it became a currency in post-war Europe.

The drug was also at the centre of Operation Claptrap, conducted by US Major Peter Chambers in the first years of the Cold War in Vienna. He offered genuine penicillin to Russian soldiers, in exchange for secrets and defection. It was an attractive offer, as venereal diseases were a court-martial offence in the Red Army.

Austria and France cooperated in 1946 to manufacture penicillin in the Alps to facilitate availability. In 1951, they developed the first oral version of the drug, as Penicillin V. The V referred to vertraulich, the German word for confidential.

In the 21st century, government action remains key to fighting both falsified and substandard medicines. Although there has been an enormous increase in global pharmaceutical manufacturing, there has been a grossly inadequate parallel investment in support for national medicine regulatory authorities (MRAs) in many countries. A key intervention to protect the drug supply in Low- and Middle-Income Countries will be investment in MRAs, the national keystones of medicine regulation.

IDDO works to strengthen knowledge of the scale of the problem of poor quality medicines and the most affected areas, and raise awareness among key stakeholders by sharing global expertise and collating information. The Antimalarial Quality Literature Surveyor, available through the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network (WWARN), is an interactive tool that visualises summaries of published reports of antimalarial medicine quality, displaying their geographical distribution across regions and over time.

The full article, ‘Fake Penicillin, The Third Man and Operation Claptrap’, can be read in the BMJ.

Researchers have charted the relationship between carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and GDP, known to scientists as global 'emission intensity'.

They have discovered that global emission intensity rose in the first part of the 21st century, despite all major climate projections foreseeing a decline. The working paper by the University of Oxford describes how earlier scenarios (created in 1992 and 2000) were overly optimistic, as recently published observations show global emissions intensity rose, largely due to unexpected economic growth in China, India and Russia. While it is important to note that scenarios were not designed to accurately project individual countries, the authors show that individual countries are the 'bear traps' of global climate scenarios as they can throw projections off course.

The paper by Dr Felix Pretis and Dr Max Roser finds the highest deviations between projections and what actually happened in the observations related to central Africa, where emission intensity rises were vastly underestimated. However, African countries made up only a relatively small share of global GDP and emissions. The main forecast failure on a global scale stemmed from projections about China, where total real GDP growth over the decade was actually around 17%, yet Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scenarios undershot this increase by 2-10%. For India, economic growth over the same period was around 10%, with IPCC scenarios showing growth up to 5% lower, and Russia's economic growth was about 6%, around 1.2-3.5% higher than the IPCC scenarios had suggested.

The authors emphasise that IPCC projections, although not forecasts per se, do not appear to be any more prone to error than alternative projections for the same time period. Creating long-term projections in an ever-changing world is challenging, and other big institutions also got it wrong, says the paper.

This study says previous scenarios commissioned by the IPCC about global emissions intensity for the period had suggested emissions would 'decouple' from economic growth and start to reduce. However, after comparing scenarios with actual observations, the researchers find 'global emissions intensity' in the first decade of the 21st century increased by 0.37% and exceeds even the closest scenario growth rate, which projected a decline of -0.1%.

Study co-author Dr Felix Pretis from the Department of Economics, co-director of the Climate Econometrics programme and James Martin Fellow at the Institute for New Economic Thinking at the Oxford Martin School, said: 'Our results find that the unexpected growth in Asia threw the social and economic projections contained in climate scenarios. This shows how unforeseen shifts caused by boom years or climate policy in individual countries can affect the overall global projections and underlines how important the actions of a few countries can be to the overall picture on global emissions intensity.

'The IPCC scenarios assumed that countries would not be as reliant on fossil fuels for their energy as they turned out to be. The belief was also that global GDP and carbon emissions would not rise at the same rate, but for the early part of the 21st century, we see that these scenarios were overly optimistic.'

While it is understood that there will also be some uncertainties around projections of temperature changes based on the physical science in climate models, the paper underlines how over the long term, social and economic shifts are even harder to assess and are highly significant for climate change projections. Unforeseen shifts in individual countries can lead to systematic errors in scenarios at the global level, the paper concludes.

Co-author Dr Max Roser commented: 'The large span of long-run projected temperature changes in climate projections does not predominately originate from uncertainties across climate models. The wide range of different global socio-economic scenarios is what creates the high uncertainty about future climate change.'

The paper raises the question of how scenarios and forecasts should be used to guide policy in the presence of shifts and instabilities. A recent Oxford Martin School policy paper also co-authored by Dr Pretis highlights the importance of accounting for instabilities when forecasting and concludes that the discovery of such forecast failures can help correct projections. His earlier paper goes on to say that in turbulent times, policymakers may even want to switch from scenarios to forecast methods that are robust to sudden changes. This would mean creating climate mitigation goals that are explicitly linked to climate responses (such as observed warming) and cumulative emissions, rather than attempting to track particular emission scenarios.

- ‹ previous

- 102 of 247

- next ›

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin

World Malaria Day 2024: an interview with Professor Philippe Guerin From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life

From health policies to clinical practice, research on mental and brain health influences many areas of public life From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage

From research to action: How the Young Lives project is helping to protect girls from child marriage  Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian

Can we truly align AI with human values? - Q&A with Brian Christian  Entering the quantum era

Entering the quantum era Can AI be a force for inclusion?

Can AI be a force for inclusion? AI, automation in the home and its impact on women

AI, automation in the home and its impact on women Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History

Inside an Oxford tutorial at the Museum of Natural History  Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI

Oxford spinout Brainomix is revolutionising stroke care through AI Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences

Oxford’s first Astrophoria Foundation Year students share their experiences