Griffith Institute

The real 'curse of Tutankhamun' is that gold mask has never been fully studied, say experts

This weekend is the last chance to see the Tutankhamun exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum. Almost 35,000 people have visited the exhibition so far, and it has been the most popular special exhibition for school groups in the history of the Museum.

The exhibition draws extensively from archival material about the discovery of the tomb, which is held by the Griffith Institute, part of the Faculty of Oriental Studies. Cat Warsi and Elizabeth Fleming of the Griffith Institute have given Arts Blog an interview about the exhibition.

The exhibition has shown the Griffith Institute to be the world’s main centre of archive material relating to the tomb of Tutankhamun. How did this come about?

Cat Warsi: About 15 years ago the then Keeper of the Griffith Institute Archive, Dr Jaromir Malek, made the decision to start an ambitious project to publish online all material housed within the Institute’s archive relating to the excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun. The excavation records, created by Howard Carter and his team from 1922 to 1932, were given to the Institute by Carter’s niece, Phyllis Walker after Carter’s death in 1939.

Carter had always planned to publish a full scientific account of all the 5398 objects found in the tomb but died before he could complete it. Due to many factors, not least the outbreak of WWII, this task was not taken on by the subsequent generations of Egyptologists – new material is constantly being discovered in Egypt and there may have been a certain amount of trepidation amongst scholars to take on objects that are so well known; coupled with the understandable security measures in place to access some of the world’s most valuable works of art.

Dr Malek felt it was an unacceptable state of affairs that so little of Carter’s Tutankhamun records had been studied and hoped that by digitising thousands of notes, photographs and plans and making them freely available online, academics could incorporate the study of objects from the tomb into their research and so continue the work Carter started 80 year ago. It took many years to completely scan, catalogue and transcribe all the material, but now that it is fully accessible to everyone we are starting to see results.

Objects from the tomb are slowly being published, with more and more Griffith Institute material being citied in research and academics requesting copies of documents or visiting Oxford to work with the originals. We are currently aware of 20 academics working on objects from the tomb, with many nearing completion within the next five years. Though it may surprise people to learn that perhaps the most famous object of all, the gold mask, has never been comprehensively studied and published; this is surely the real ‘curse of Tutankhamun’.

What do you hope will be the exhibition’s legacy?

CW: The Griffith Institute is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year but, in partnership with the Ashmolean Museum, this is our first ever public exhibition. Whilst Egyptologists may know of our existence, this has given us a real public platform to engage with people and showcase some of the ‘wonderful things’ we have in our Archive. It’s given us the opportunity (in collaboration with the British Museum) to produce learning resources for families and schools which will live on and grow after the exhibition closes.

Elizabeth Fleming: Whilst sourcing archive material for the exhibition we have become aware of the ‘gap’ within our Tutankhamun Archive which documents the huge global impact the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun had on the world, from the moment of discovery in November 1922 which has continued to the present day. As a consequence the Archive is actively collecting and preserving documents such as original newspaper reports, Tutankhamun/ancient Egyptian themed advertisements, sheet music, cigarette cards, period photographs and costume jewellery.

CW: In amongst all the myths, theories and curse stories surrounding the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun we hope we’ve given the public thought-provoking facts and information from which they can decide what to believe and continue researching if we’ve sparked their interest. If we've been able to communicate just a fraction of the love and excitement we have for our subject then the exhibition will have been a success.

Do you hope it encourages young people to consider studying Egyptology and archaeology?

CW: One of the first objects visitors see when entering the exhibition is a beautiful watercolour by Howard Carter painted many years before the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. Having grown up and been home-schooled in a small village in Norfolk, Carter first travelled to Egypt when he was just 17 in order to draw and paint scenes in tombs and temples.

We hope young people will be inspired by Carter’s story but that it also shows the patience, passion and dedication needed to pursue such a career. Little has changed since the 1920’s in as much as the hours are long, the jobs are few and discoveries may be a long time coming – Carter didn’t discover Tutankhamun’s tomb until he was 48!

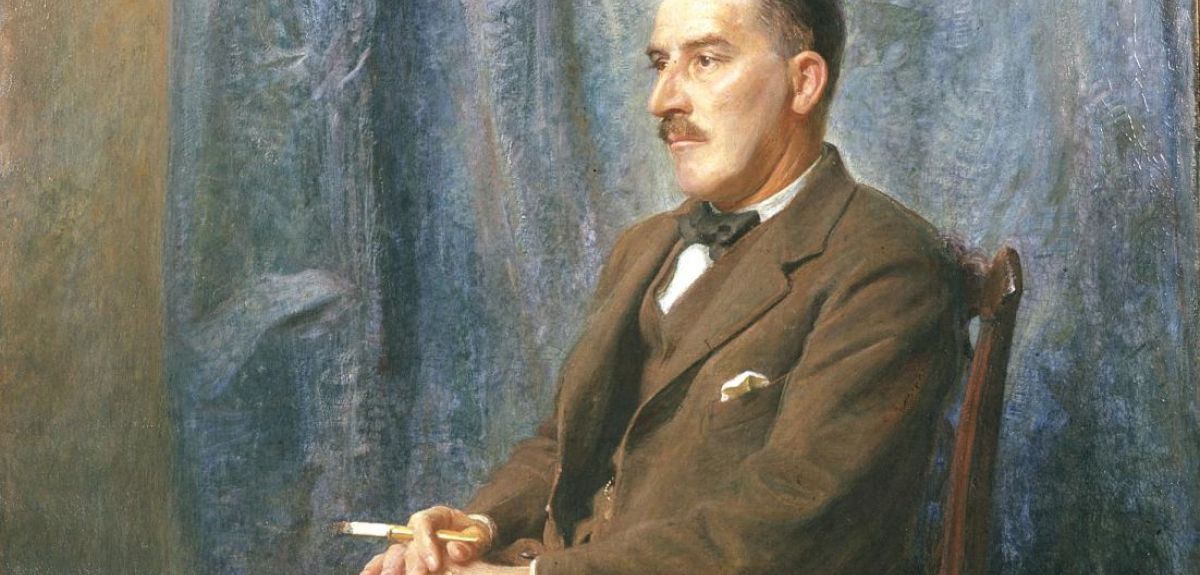

EF: The last object in the exhibition is another painting, this time the subject is Howard Carter himself. This portrait painted by Howard’s brother William, was created not long after the discovery of the tomb, he is shown seated staring into the middle distance which allows the viewer to imagine that Howard Carter is reflecting on his great accomplishment.

The curators of the exhibition invite young exhibition visitors to contemplate Howard Carter’s great achievement too, and if they are contemplating a career in Egyptology, to consider continuing Carter’s work on publishing all of the objects found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, which even now, 92 years after the discovery, leaves 70% of the tomb’s contents not properly studied and published.

How has the feedback been?

CW: We’ve been absolutely delighted with the many reviews the exhibition has received; people seem to have understood the narrative we were trying to get across and our motivations in staging ‘yet another’ exhibition on Tutankhamun, albeit from a very different angle. We all have our favourite items we hope our audience has discovered, but one of the most popular amongst reviewers seems to have been a wonderfully illustrated item of Carter’s ‘fan mail’ written by a six year old Irish boy wishing he ‘was an Egyptolisty’ like Carter. Of course feedback also highlights things we could have done better and although we may not have another exhibition in the immediate future we can apply constructive comments to archive material published on our ever expanding website.

Has the exhibition led to any unexpected results?

CW: As hoped, the exhibition has highlighted our existence amongst non-specialists and we have already received two donations of archive material from a members of the public as a consequence. We’ve received more enquiries generally concerning Tutankhamun – along with the many other benefits we hope this exhibition has made us more approachable.

The exhibition has also given us the opportunity to get in touch with old friends, including the grandson of Arthur Mace, a member of Carter’s team, who very kindly donated some family papers to the Archive.

One of our aims for the exhibition was to highlight Carter’s early work in Egypt as an artist, a passion that he sustained throughout his life but something many are not aware of. While visiting us Mace’s descendent told us a fantastic story passed on by his grandfather, that whenever Carter (a man notorious for his bad temper) had a real bee in his bonnet Mace would send him out of the tomb, telling him to go and paint in order to calm down.

EF: As many of the contemporary records for the discovery and excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun are black and white, visitors have a unique opportunity to view the treasures of the tomb without the ‘distraction’ of gold. As a consequence, we’ve been asked many more questions about the less familiar material from the tomb during tours of the exhibition.

A recurring question from visitors who were especially intrigued by a line of boat oars carefully placed in antiquity along the floor next to Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus, the oars ritualistically represented the boat that the King would use on his journey through the Underworld where he would have to face many obstacles and challenges before he was allowed to be reborn in the Afterlife. This is just one example of visitors being able to engage with the hidden gem buried with Tutankhamun, often overshadowed by the more spectacular gold items from the tomb, such as the iconic solid gold mask of Tutankhamun.

The exhibition will remain open until Sunday 2 November. A special 'Live Friday' event will be held this evening (31 October) from 7.30pm-10pm. Admission is free.

If you have been inspired by the exhibition to consider studying Ancient Egypt, Oxford University is a leading centre for undergraduate and postgraduate study in the field. More information is available here.